Sebaceous carcinoma

Sebaceous carcinoma, also known as sebaceous gland carcinoma (SGc), sebaceous cell carcinoma, and mebomian gland carcinoma is an uncommon and aggressive malignant cutaneous tumor.[1] Most are typically about 10 mm in size at presentation.[2] This neoplasm is thought to arise from sebaceous glands in the skin and, therefore, may originate anywhere in the body where these glands are found. Sebaceous carcinoma can be divided into 2 types: ocular and extraocular. Because the periocular region is rich in this type of gland, this region is a common site of origin.[3][4] The cause of these lesions are, in the vast majority of cases, unknown. Occasional cases may be associated with Muir-Torre syndrome.[5][6] Due to the rarity of this tumor and variability in clinical and histological presentation, SGc is often misdiagnosed as an inflammatory condition or a more common type of tumor.[7]

| Sebaceous carcinoma | |

|---|---|

| |

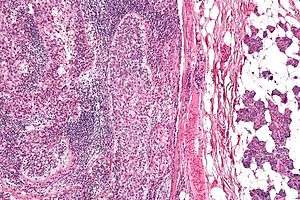

| Micrograph of a sebaceous carcinoma (left of image) metastatic to the parotid gland (right of image). H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Oncology, dermatology |

Currently the ocular SGc is commonly treated with wide surgical resection or Moh's micrographic surgery.[8]

This type of cancer usually has a poor prognosis because of a high rate of metastasis.[2]

Presentation

Sebaceous carcinoma is a skin cancer of the sebum producing glands. It is predominantly seen in the head and neck region, representing 25% of all reported lesions in this area.[9] The periocular region, which includes the meibomian gland, caruncle, gland of Zeis and eyebrow, is one of the most common sites in which SC is observed.[10] The meibomian gland is a type of sebaceous gland that lines the upper and lower eyelids, and does not contain a follicle. The glands of Zeis contain the individual eyelash.[11] The upper eyelid contains more meibomian glands than the lower eyelid and consequently, SGc is 2-3 times more common in the upper eyelid.[12]

Patients diagnosed with SGc most commonly present with a painless subcutaneous nodule. Other presentations include an irregular mass, pedunculated lesion or diffuse skin thickening.[13] SGc in the periocular region presents as a heterogeneous rapidly growing, pink or yellow colored painless papule.[14]

Pathophysiology

The cell of origin is usually unknown. Sebaceous gland carcinoma clearly resembles normal sebaceous glands and is thought to arise from them.[1][2] Ultraviolet and ionizing radiation are believed to play some role in the pathogenesis of these neoplasms.[11] There is a strong association between Muir–Torre syndrome.

There has been an association between the development of sebaceous carcinoma with the following: history of irradiation, immunosuppression, and genetic factors.[11]

One possible hypothesis states that stem cells in the hair follicle bulge and suprabasilar layer respond to different environmental stimuli, such as radiation, that may lead to the development of cutaneous tumors.[15] Immunosuppressed individuals and those undergoing radiotherapy are at an increased risk for SGc. There has been some association between SGc and HIV, HPV (human papillomavirus) and mutations in tumor suppressor genes p53 and Rb. Rb mutations are responsible for retinoblastoma.[12][8] Reports have also shown the onset of SGc within the field of irradiation for patients undergoing radiotherapy for retinoblastoma, eczema or cosmetic epilation.[7]

In addition to external factors, genes also appear to play some role in the pathogenesis of this tumor. Extraocular SGc is closely associated with Muir Torre syndrome (MTS), with sebaceous tumors presenting in nearly 1/3 of patients with MTS.[8]

MTS is an autosomal genodermatosis, described as a condition with 2 types of malignancies: one being a sebaceous gland tumor and the other an internal malignancy, a majority of which are colorectal and genitourinary.[5] In 41% of patients with MTS skin lesions appeared either before or during the time of diagnosis of the primary malignancy.[5]

Studies have shown that cancerous lesions in MTS develop as a result of mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes (MMR), which lead to a buildup of unstable microsatellite sequences and replications errors, predisposing one to different malignancies.[10][5] Given that this is an autosomal dominant condition with multiorgan involvement, diagnosis requires a thorough medical history and physical in suspected cases of SGc in order to rule out potential visceral tumors.

A number of SGc associated mutated proteins (B-catenin, p 53, p21, Shh, Androgen receptor, E-cadherin) have been shown to cause dysregulation in cell signaling. This dysregulation is responsible for the invasive growth and metastasis of SGc and identification of specific mutations could help determine patient prognosis and clinical outcomes.[12]

Diagnosis

Due to the variable clinical and histological appearance of SGc, this condition is often misdiagnosed. The average delay in diagnosis has been reported to be 1 – 2.9 years from expected onset of the lesion.[14][7]

Patients with ocular sebaceous carcinomas present with nonhealing eyelid tumors that are often misdiagnosed for more common benign conditions such as chalazion or blepharoconjunctivitis. Extraocular SGc appears similarly to skin cancers such as basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and benign lesions such a molluscum contagiosum and pyogenic granuloma.[14] Many tumors also share a histological presentation similar to SGC, such as sebaceous adenomas, basal cell carcinomas (BCC), squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) and clear cell tumors.[11][14] A high level of suspicion is extremely important to prevent treatment delay and increased mortality.[11]

Given the aggressive growth and pagetoid spread of SGC, full thickness biopsy with microscopic examination is required for definitive diagnosis of sebaceous carcinomas.[10] A full thickness biopsy of the eyelid (in suspected periocular SGC) includes the skin, tarsus, and palpebral conjunctiva.[7] Map biopsies, taken from distinct areas of the conjunctiva, are recommended in cases exhibiting pagetoid spread in order to determine extent of disease.[10] Different markers and stains help differentiate sebaceous carcinomas from other cancers. These markers include lipid stains such as oil red O stain and Sudan IV, and immunohistochemical stains.[13]

Morphology

SGc is classified based on histopathological presentation, including cytoarchitecture, cytology, and pattern of growth. The lobular variant is the most common histological pattern followed by papillary, comedocarcinoma and mixed.[3] Tumors may be also classified by differentiation, from poor to well differentiated. Well- and moderately differentiated sebaceous carcinoma tend to exhibit vacuolization within the cytoplasm of the tumor cells.[16] This is known as sebocytic differentiation, where the vacuolization is caused by lipid containing cytoplasmic vacuoles that present as round clear areas in the cell.[11] Periocular sebaceous gland carcinoma exhibits pagetoid (intraepithelial) spread, an upward growth of abnormal cells invading the epidermis, it is most often seen in the lid margin and/or conjunctiva.[12] Periorbital SGC also presents with multicentric origins, in the upper and lower eyelids, increasing the risk of local recurrence.[8]

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical stains are also used when there are inadequate tissue samples or after microscopic examination, and are extremely useful in dermatopathology. Specific antigens such as epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cytokeratin -7 (CK-7), Ber-EP4 and androgen receptor (AR) can be targeted in order to differentiate SGc from BCC or SCC.[11]

Tissue immunohistochemistry is also used is used to diagnose MTS. Expression of 4 DNA mismatch repair proteins (MSH2, MLH1, PMS1 and PMS2) along with medical history, followed by genetic evaluation for microsatellite instability and germline mutation testing is used to screen for MTS in patients diagnosed with sebaceous neoplasms.[8]

Sentinel lymph node biopsy

Despite the risk of metastatic spread, there has been little research on the utility of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). Since periocular tumor have a higher rate of regional metastasis, SLNB is suggested for all ocular SGc tumors greater than 10mm in diameter.[10] Treatment for nodal metastasis confirmed via SLNB involves advanced imaging studies [CT with or without PET scan], followed by removal of the primary tumor and regional lymph nodes, with adjuvant radiotherapy.[8] However, it is important to note there has been no evidence of decreased mortality in those who had SLNB identified lymph node involvement. In addition, subsequent risks associated with surgical and radiotherapy may increase morbidity.[10]

Staging

Sebaceous carcinomas are staged according to The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Tumor, Node, Metastasis (TNM) guidelines for nonmelanoma skin cancers.[10] This classification system has different stages for ocular and extraocular tumors, given that periocular tumors have a higher risk for metastasis and recurrence.[8]

Treatment

This type of carcinoma is commonly managed by local resection, cryotherapy, topical chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Multimodal therapy has been shown to improve both visual prognosis and survival.[3]

Surgical resection

Wide local excision, which has been replaced by Mohs micrographic surgery had been the primary treatment for both ocular and extraocular sebaceous carcinoma.[14]

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has become the gold standard of treatment for SGc. MMS allows for precise and accurate removal of the tumor and complete assessment of margins.[8] Furthermore, MMS is associated with significantly lower local and distant recurrence rates in both periocular and extraocular SC, when compared to wide local excision. MMS also limits morbidity and is useful in cosmetically sensitive areas such as the face.[8][4][17]

Chemotherapy

There is a limited amount of information on the effectiveness of chemotherapy or chemoradiation, and is not indicated for local tumors.[14] Chemotherapy may be used in advanced tumors, to allow for local resection and in order to avoid exenteration [total removal of the eyeball and contents of the eye socket]. These treatments typically use 5-fluorouracil or cisplatin, also used in head and neck cancers.[8] Few studies have shown that topical adjuvant chemotherapy is also effective in treating periocular SGC.[10]

Radiation therapy

Radiotherapy is associated with higher recurrence rates and mortality when compared to surgical excision. It is not recommended as a primary therapy and is only for patients who cannot undergo surgical excision.[8] Potential adverse effects from radiation include keratitis, conjunctivitis, dry eyes, keratitis and loss of vision.[14]

Cryotherapy

Although uncommon, conjunctival cryotherapy used during surgical excision has also been reported, but the associated risks to one’s vision and potential damage to the eye appear to outweigh its benefits.[8]

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has become the treatment of choice for this form of cancer. Mohs surgery allows for precise and accurate removal of the complete tumor and surrounding margins via frozen section.[8] When used as the primary treatment modality for sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid, Mohs surgery is associated with significantly lower local and distant recurrence rates.[4][17]

Prognosis

The 5-year relative survival rate for SGc is 92.72% and 86.98% for 10 years. SGc is believed to spread through the blood and lymphatic system via three mechanisms: tumor growth, multifocal tumor proliferation and shedding of atypical epithelial cells that subsequently transplant in a distant site.[14] Common sites of metastasis for periorbital SGc are regional lymph nodes and rarely in the lung, liver, brain or bone.[8] Due to the difficulty associated with promptly diagnosing SGc tumor, the rate of metastasis and recurrence is relatively high.[11] Approximately 10% of patients with poorly or undifferentiated SGc presented with regional lymph node involvement.[14] At the time of diagnosis nearly 25% of tumors will metastasize, in those with metastasizing cancer survival rate decreases to 50% within 5 years.[11] Recurrence rates are higher in ocular vs extraocular tumors, 4-37% and 4-29% respectively. Over time there has been a notable improvement in prognosis in those with SGc, which is most likely attributable to earlier detection and improved treatment modalities.[13]

Epidemiology

Notable risk factors include age, gender, and race. In the United States sebaceous is relatively rare, contributing to only 0.7% of all skin cancers.[8] SGc is more prevalent in the Eastern versus Western Hemisphere, contributing to 33% of eyelid malignancies in China vs 1-5.5% in Caucasians.[3][12] However, it is believed the higher incidence of SGc in Asian populations may be due to the lower incidence of other eyelid tumors.[12] Additionally, a higher incidence has been reported in Caucasians, Asians, and Indians.[7] This skin cancer typically occurs in the elderly, with a reported average age of onset in the 60 to early 70s.[10] Different sources have also reported that SGc may be more common within females versus males, but other resources report no difference in incidence.[8]

See also

References

- Nelson BR, Hamlet KR, Gillard M, Railan D, Johnson TM (July 1995). "Sebaceous carcinoma". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 33 (1): 1–15, quiz 16–8. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90001-2. PMID 7601925.

- Rao NA, Hidayat AA, McLean IW, Zimmerman LE (February 1982). "Sebaceous carcinomas of the ocular adnexa: A clinicopathologic study of 104 cases, with five-year follow-up data". Human Pathology. 13 (2): 113–22. doi:10.1016/S0046-8177(82)80115-9. PMID 7076199.

- Shields JA, Demirci H, Marr BP, Eagle RC, Shields CL (2005). "Sebaceous carcinoma of the ocular region: a review". Survey of Ophthalmology. 50 (2): 103–22. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2004.12.008. PMID 15749305.

- Callahan EF, Appert DL, Roenigk RK, Bartley GB (August 2004). "Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid: a review of 14 cases". Dermatologic Surgery. 30 (8): 1164–8. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30348.x. PMID 15274713.

- Cohen PR (August 1992). "Sebaceous carcinomas of the ocular adnexa and the Muir-Torre syndrome". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 27 (2 Pt 1): 279–80. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(08)80752-9. PMID 1430382.

- Rishi K, Font RL (January 2004). "Sebaceous gland tumors of the eyelids and conjunctiva in the Muir-Torre syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of five cases and literature review". Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 20 (1): 31–6. doi:10.1097/01.IOP.0000103009.79852.BD. PMID 14752307.

- Buitrago, William; Joseph, Aaron K. (November 2008). "Sebaceous carcinoma: the great masquerader: emerging concepts in diagnosis and treatment". Dermatologic Therapy. 21 (6): 459–466. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00247.x. ISSN 1529-8019. PMID 19076624.

- Kyllo RL, Brady KL, Hurst EA (January 2015). "Sebaceous carcinoma: review of the literature". Dermatologic Surgery. 41 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000000152. PMID 25521100.

- Wick MR, Goellner JR, Wolfe JT, Su WP (September 1985). "Adnexal carcinomas of the skin. II. Extraocular sebaceous carcinomas". Cancer. 56 (5): 1163–72. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19850901)56:5<1163::AID-CNCR2820560533>3.0.CO;2-A. PMID 4016704.

- Orr CK, Yazdanie F, Shinder R (September 2018). "Current review of sebaceous cell carcinoma". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 29 (5): 445–450. doi:10.1097/icu.0000000000000505. PMID 29985175.

- Morgan M.B. (2010) Sebaceous Tumors. In: Morgan M., Hamill J., Spencer J. (eds) Atlas of Mohs and Frozen Section Cutaneous Pathology. Springer, New York, NY.

- Mulay K, Aggarwal E, White VA (July 2013). "Periocular sebaceous gland carcinoma: A comprehensive review". Saudi Journal of Ophthalmology. 27 (3): 159–65. doi:10.1016/j.sjopt.2013.05.002. PMC 3770214. PMID 24227981.

- Eisen, Daniel B.; Michael, Daniel J. (October 2009). "Sebaceous lesions and their associated syndromes: part I". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 61 (4): 549–560, quiz 561–562. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.04.058. ISSN 1097-6787. PMID 19751879.

- Knackstedt T, Samie FH (August 2017). "Sebaceous Carcinoma: A Review of the Scientific Literature". Current Treatment Options in Oncology. 18 (8): 47. doi:10.1007/s11864-017-0490-0. PMID 28681210.

- Gerdes, Michael J.; Yuspa, Stuart H. (2005). "The contribution of epidermal stem cells to skin cancer". Stem Cell Reviews. 1 (3): 225–231. doi:10.1385/SCR:1:3:225. ISSN 1550-8943. PMID 17142859.

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Seventh Edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2005, p. 1425.

- Spencer JM, Nossa R, Tse DT, Sequeira M (June 2001). "Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid treated with Mohs micrographic surgery". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 44 (6): 1004–9. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.113692. PMID 11369914.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |