Sciatica

Sciatica is a health condition characterized by pain going down the leg from the lower back.[1] This pain may go down the back, outside, or front of the leg.[3] Onset is often sudden following activities like heavy lifting, though gradual onset may also occur.[5] The pain is often described as shooting.[1] Typically, symptoms are only on one side of the body.[3] Certain causes, however, may result in pain on both sides.[3] Lower back pain is sometimes present.[3] Weakness or numbness may occur in various parts of the affected leg and foot.[3]

| Sciatica | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Sciatic neuritis, sciatic neuralgia, lumbar radiculopathy, radicular leg pain |

| |

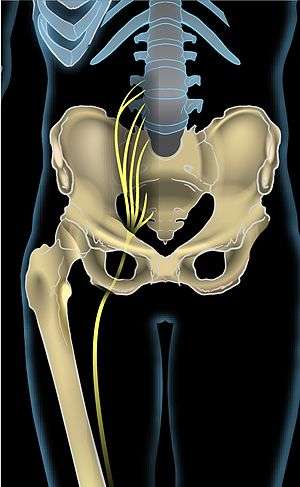

| Anterior view showing the sciatic nerve going down the right leg | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Orthopedics, neurology |

| Symptoms | Pain going down the leg from the lower back, weakness or numbness of the affected leg[1] |

| Complications | Loss of bowel or bladder control[2] |

| Usual onset | 40s–50s[2][3] |

| Duration | 90% of the time less than 6 weeks[2] |

| Causes | Spinal disc herniation, spondylolisthesis, spinal stenosis, piriformis syndrome, pelvic tumor[3][4] |

| Diagnostic method | Straight-leg-raising test[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Shingles, diseases of the hip[3] |

| Treatment | Pain medications, surgery[2] |

| Frequency | 2–40% of people at some time[4] |

About 90% of sciatica is due to a spinal disc herniation pressing on one of the lumbar or sacral nerve roots.[4] Spondylolisthesis, spinal stenosis, piriformis syndrome, pelvic tumors, and pregnancy are other possible causes of sciatica.[3] The straight-leg-raising test is often helpful in diagnosis.[3] The test is positive if, when the leg is raised while a person is lying on their back, pain shoots below the knee.[3] In most cases medical imaging is not needed.[2] However, imaging may be obtained if bowel or bladder function is affected, there is significant loss of feeling or weakness, symptoms are long standing, or there is a concern for tumor or infection.[2] Conditions that may present similarly are diseases of the hip and infections such as early shingles (prior to rash formation).[3]

Initial treatment typically involves pain medications.[2] Though evidence for pain medication and muscle relaxants is lacking.[6] It is generally recommended that people continue with normal activity to the best of their abilities.[3] Often all that is required for sciatica resolution is time; in about 90% of people symptoms resolve in less than six weeks.[2] If the pain is severe and lasts for more than six weeks, surgery may be an option.[2] While surgery often speeds pain improvement, its long term benefits are unclear.[3] Surgery may be required if complications occur, such as loss of normal bowel or bladder function.[2] Many treatments, including corticosteroids, gabapentin, pregabalin, acupuncture, heat or ice, and spinal manipulation, have limited or poor evidence for their use.[3][7][8]

Depending on how it is defined, less than 1% to 40% of people have sciatica at some point in time.[4][9] It is most common during people's 40s and 50s, and men are more frequently affected than women.[2][3] The condition has been known since ancient times.[3] The first known use of the word sciatica dates from 1451.[10]

Definition

The term "sciatica" usually describes a symptom—pain along the sciatic nerve pathway—rather than a specific condition, illness, or disease.[4] Some use it to mean any pain starting in the lower back and going down the leg.[4] The pain is characteristically described as shooting or shock-like, quickly traveling along the course of the affected nerves.[11] Others use the term as a diagnosis (i.e. an indication of cause and effect) for nerve dysfunction caused by compression of one or more lumbar or sacral nerve roots from a spinal disc herniation.[4] Pain typically occurs in the distribution of a dermatome and goes below the knee to the foot.[4][6] It may be associated with neurological dysfunction, such as weakness and numbness.[4]

Causes

Risk factors

Modifiable risk factors for sciatica include smoking, obesity and occupation.[9] Non-modifiable risk factors include increasing age, being male, and having a personal history of low back pain.[9]

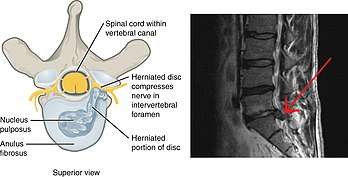

Spinal disc herniation

Spinal disc herniation pressing on one of the lumbar or sacral nerve roots is the most frequent cause of sciatica, being present in about 90% of cases.[4] This is particularly true in those under age 50.[12] Disc herniation most often occurs during heavy lifting.[13] Pain typically increases when bending forward or sitting, and reduces when lying down or walking.[12] Sciatica caused by pressure from a disc herniation, and swelling of surrounding tissue, can spontaneously subside if the tear in the disc heals and the pulposus extrusion and inflammation cease.

Spinal stenosis

Other compressive spinal causes include lumbar spinal stenosis, a condition in which the spinal canal, the space the spinal cord runs through, narrows and compresses the spinal cord, cauda equina, or sciatic nerve roots.[14] This narrowing can be caused by bone spurs, spondylolisthesis, inflammation, or a herniated disc, which decreases available space for the spinal cord, thus pinching and irritating nerves from the spinal cord that become the sciatic nerve.[14] This is the most frequent cause after age 50.[12] Sciatic pain due to spinal stenosis is most commonly brought on by standing, walking, or sitting for extended periods of time, and reduces when bending forward.[12][14] However, pain can arise with any position or activity in severe cases.[14] The pain is most commonly relieved by rest.[14]

Piriformis syndrome

Piriformis syndrome is a condition that, depending on the analysis, varies from a "very rare" cause to contributing up to 8% of low back or buttock pain.[15] In 17% of people, the sciatic nerve runs through the piriformis muscle rather than beneath it.[14] When the piriformis shortens or spasms due to trauma or overuse, it is posited that this causes compression of the sciatic nerve.[15] Piriformis syndrome has colloquially been referred to as "wallet sciatica" since a wallet carried in a rear hip pocket compresses the buttock muscles and sciatic nerve when the bearer sits down. Piriformis syndrome may be suspected as a cause of sciatica when the spinal nerve roots contributing to the sciatic nerve are normal and no herniation of a spinal disc is apparent.[16][17]

Pregnancy

Sciatica may also occur during pregnancy, especially during later stages, as a result of the weight of the fetus pressing on the sciatic nerve during sitting or during leg spasms.[14] While most cases do not directly harm the woman or the fetus, indirect harm may come from the numbing effect on the legs, which can cause loss of balance and falls. There is no standard treatment for pregnancy-induced sciatica.[18]

Other

Pain that does not improve when lying down suggests a nonmechanical cause, such as cancer, inflammation, or infection.[12] Sciatica can be caused by tumors impinging on the spinal cord or the nerve roots.[4] Severe back pain extending to the hips and feet, loss of bladder or bowel control, or muscle weakness may result from spinal tumors or cauda equina syndrome.[14] Trauma to the spine, such as from a car accident or hard fall onto the heel or buttocks, may also lead to sciatica.[14] A relationship has been proposed with a latent Cutibacterium acnes infection in the intervertebral discs, but the role it plays is not yet clear.[19][20]

Pathophysiology

Sciatica is generally caused by the compression of lumbar nerves L4 or L5 or sacral nerve S1.[21] Less commonly, sacral nerves S2 or S3 or compression of the sciatic nerve itself may cause sciatica.[21] In 90% of sciatica cases, this can occur as a result of a spinal disc bulge or herniation.[13] Intervertebral spinal discs consist of an outer anulus fibrosus and an inner nucleus pulposus.[13] The anulus fibrosus forms a rigid ring around the nucleus pulposus early in human development, and the gelatinous contents of the nucleus pulposus are thus contained within the disc.[13] Discs separate the spinal vertebrae, thereby increasing spinal stability and allowing nerve roots to properly exit through the spaces between the vertebrae from the spinal cord.[22] As an individual ages, the anulus fibrosus weakens and becomes less rigid, making it at greater risk for tear.[13] When there is a tear in the anulus fibrosus, the nucleus pulposus may extrude through the tear and press against spinal nerves within the spinal cord, cauda equina, or exiting nerve roots, causing inflammation, numbness, or excruciating pain.[23] Inflammation of spinal tissue can then spread to adjacent facet joints and cause facet syndrome, which is characterized by lower back pain and referred pain in the posterior thigh.[13]

Other causes of sciatica secondary to spinal nerve entrapment include the roughening, enlarging, or misalignment (spondylolisthesis) of vertebrae, or disc degeneration that reduces the diameter of the lateral foramen through which nerve roots exit the spine.[13] When sciatica is caused by compression of a dorsal nerve root, it is considered a lumbar radiculopathy or radiculitis when accompanied by an inflammatory response.[14] Sciatica-like pain prominently focused in the buttocks can also be caused by compression of peripheral sections of the sciatic nerve usually from soft tissue tension in the piriformis or related muscles.[13]

Diagnosis

Sciatica is typically diagnosed by physical examination, and the history of the symptoms.[4]

Physical tests

Generally if a person reports the typical radiating pain in one leg as well as one or more neurological indications of nerve root tension or neurological deficit, sciatica can be diagnosed.[24]

The most applied diagnostic test is the straight leg raise to produce Lasègue's sign, which is considered positive if pain in the distribution of the sciatic nerve is reproduced with passive flexion of the straight leg between 30 and 70 degrees.[25] While this test is positive in about 90% of people with sciatica, approximately 75% of people with a positive test do not have sciatica.[4] Straight raising the leg unaffected by sciatica may produce sciatica in the leg on the affected side; this is known as the Fajersztajn sign.[14] The presence of the Fajersztajn sign is a more specific finding for a herniated disc than Lasègue's sign.[14] Maneuvers that increase intraspinal pressure, such as coughing, flexion of the neck, and bilateral compression of the jugular veins, may worsen sciatica.[14]

Medical imaging

Imaging modalities such as computerised tomography or magnetic resonance imaging can help with the diagnosis of lumbar disc herniation.[26] The utility of MR neurography in the diagnosis of piriformis syndrome is controversial.[15]

Discography could be considered to determine a specific disc's role in an individual's pain.[13] Discography involves the insertion of a needle into a disc to determine the pressure of disc space.[13] Radiocontrast is then injected into the disc space to assess for visual changes that may indicate an anatomic abnormality of the disc.[13] The reproduction of an individual's pain during discography is also diagnostic.[13]

Differential diagnosis

Cancer should be suspected if there is previous history of it, unexplained weight loss, or unremitting pain.[12] Spinal epidural abscess is more common among those with diabetes mellitus or immunocompromised or who had spinal surgery, injection or catheter; it typically causes fever, leukocytosis and increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate.[12] If cancer or spinal epidural abscess are suspected, urgent magnetic resonance imaging is recommended for confirmation.[12] Proximal diabetic neuropathy typically affects middle aged and older people with well-controlled type-2 diabetes mellitus; onset is sudden causing pain usually in multiple dermatomes quickly followed by weakness. Diagnosis typically involves electromyography and lumbar puncture.[12] Shingles is more common among the elderly and immunocompromised; usually (but not always) pain is followed by appearance of a rash with small blisters along a single dermatome.[12][27] Acute Lyme radiculopathy may follow a history of outdoor activities during warmer months in likely tick habitats in the previous 1–12 weeks.[28] In the U.S., Lyme is most common in New England and Mid-Atlantic states and parts of Wisconsin and Minnesota, but it is expanding to other areas.[29][30] The first manifestation is usually an expanding rash possibly accompanied by flu-like symptoms.[31] Lyme can also cause a milder, chronic radiculopathy an average of 8 months after the acute illness.[12]

Management

Sciatica can be managed with a number of different treatments[32] with the goal of restoring a person's normal functional status and quality of life.[13] When the cause of sciatica is lumbar disc herniation (90% of cases),[4] most cases resolve spontaneously over weeks to months.[33] Initially treatment in the first 6–8 weeks should be conservative.[4] More than 75% of sciatica cases are managed without surgery.[13] In persons that smoke who also have sciatica, smoking cessation should be strongly considered.[13] Treatment of the underlying cause of nerve compression is needed in cases of epidural abscess, epidural tumors, and cauda equina syndrome.[13]

Physical activity

Physical activity is often recommended for the conservative management of sciatica for persons that are physically able.[3] However, the difference in outcomes between physical activity compared to bed rest have not been fully elucidated.[3][34] The evidence for physical therapy in sciatica is unclear though such programs appear safe.[3] Physical therapy is commonly used.[3] Nerve mobilization techniques for sciatic nerve is supported by tentative evidence.[35]

Medication

There is no one medication regimen used to treat sciatica.[32] Evidence supporting the use of opioids and muscle relaxants is poor.[36] Low-quality evidence indicates that NSAIDs do not appear to improve immediate pain and all NSAIDs appear about equivalent in their ability to relieve sciatica.[36][37][38] Nevertheless, NSAIDs are commonly recommended as a first-line treatment for sciatica.[32] In those with sciatica due to piriformis syndrome, botulinum toxin injections may improve pain and function.[39] While there is little evidence supporting the use of epidural or systemic steroids,[40][41] systemic steroids may be offered to individuals with confirmed disc herniation if there is a contraindication to NSAID use.[32] Low-quality evidence supports the use of gabapentin for acute pain relief in those with chronic sciatica.[36] Anticonvulsants and biologics have not been shown to improve acute or chronic sciatica.[32] Antidepressants have demonstrated some efficacy in treating chronic sciatica and may be offered to individuals who are not amenable to NSAIDs or who have failed NSAID therapy.[32]

Surgery

If sciatica is caused by a herniated disc, the disc's partial or complete removal, known as a discectomy, has tentative evidence of benefit in the short term.[42] If the cause is spondylolisthesis or spinal stenosis, surgery appears to provide pain relief for up to two years.[42]

Alternative medicine

Acupuncture has been shown to improve sciatica-related pain, though the supporting evidence is limited by small study samples.[32] Low to moderate-quality evidence suggests that spinal manipulation is an effective treatment for acute sciatica.[3][43] For chronic sciatica, the evidence supporting spinal manipulation as treatment is poor.[43] Spinal manipulation has been found generally safe for the treatment of disc-related pain; however, case reports have found an association with cauda equina syndrome,[44] and it is contraindicated when there are progressive neurological deficits.[45]

Prognosis

About 39 to 50% of people still have symptoms after 1 to 4 years.[46] About 20% in one study were unable to work at a year and 10% had had surgery for the condition.[46]

Epidemiology

Depending on how it is defined, less than 1% to 40% of people have sciatica at some point in time.[9][4] Sciatica is most common during people's 40s and 50s and men are more frequently affected than women.[2][3]

References

- "Sciatica". Archived from the original on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (October 9, 2014). "Slipped disk: Overview". Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- Ropper, AH; Zafonte, RD (26 March 2015). "Sciatica". The New England Journal of Medicine. 372 (13): 1240–8. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1410151. PMID 25806916.

- Valat, JP; Genevay, S; Marty, M; Rozenberg, S; Koes, B (April 2010). "Sciatica". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 24 (2): 241–52. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2009.11.005. PMID 20227645.

- T.J. Fowler; J.W. Scadding (28 November 2003). Clinical Neurology, 3Ed. CRC. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-340-80798-9.

- Koes, B W; van Tulder, M W; Peul, W C (2007-06-23). "Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica". BMJ : British Medical Journal. 334 (7607): 1313–1317. doi:10.1136/bmj.39223.428495.BE. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1895638. PMID 17585160.

- Markova, Tsvetio (2007). "Treatment of Acute Sciatica". Am Fam Physician. 75 (1): 99–100. PMID 17225710. Archived from the original on 2016-02-02.

- Enke O, New HA, New CH, Mathieson S, McLachlan AJ, Latimer J, Maher CG, Lin CC (July 2018). "Anticonvulsants in the treatment of low back pain and lumbar radicular pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis". CMAJ. 190 (26): E786–E793. doi:10.1503/cmaj.171333. PMC 6028270. PMID 29970367.

- Cook CE, Taylor J, Wright A, Milosavljevic S, Goode A, Whitford M (June 2014). "Risk factors for first time incidence sciatica: a systematic review". Physiother Res Int. 19 (2): 65–78. doi:10.1002/pri.1572. PMID 24327326.

- Simpson, John (2009). Oxford English dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199563838.

- Bhat, Sriram (2013). SRB's Manual of Surgery. p. 364. ISBN 9789350259443.

- Tarulli AW, Raynor EM (May 2007). "Lumbosacral radiculopathy" (PDF). Neurologic Clinics. 25 (2): 387–405. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2007.01.008. PMID 17445735.

- Butterworth IV, John F. (2013). Morgan & Mikhail's Clinical Anesthesiology. David C. Mackey, John D. Wasnick (5th. ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. Chapter 47. Chronic Pain Management. ISBN 9780071627030. OCLC 829055521.

- Ropper, Allan H. (2014). Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. Samuels, Martin A., Klein, Joshua P. (Tenth ed.). New York. pp. Chapter 11. Pain in the Back, Neck, and Extremities. ISBN 9780071794794. OCLC 857402060.

- Miller TA, White KP, Ross DC (September 2012). "The diagnosis and management of Piriformis Syndrome: myths and facts". Can J Neurol Sci. 39 (5): 577–83. doi:10.1017/s0317167100015298. PMID 22931697.

- Kirschner JS, Foye PM, Cole JL (July 2009). "Piriformis syndrome, diagnosis and treatment". Muscle Nerve. 40 (1): 10–18. doi:10.1002/mus.21318. PMID 19466717.

- Lewis AM, Layzer R, Engstrom JW, Barbaro NM, Chin CT (October 2006). "Magnetic resonance neurography in extraspinal sciatica". Arch. Neurol. 63 (10): 1469–72. doi:10.1001/archneur.63.10.1469. PMID 17030664.

- Sciatic Nerve Pain During Pregnancy: Causes and Treatment. American Pregnancy Association. Published September 20, 2017. Accessed November 12, 2018.

- Ganko R, Rao PJ, Phan K, Mobbs RJ (May 2015). "Can bacterial infection by low virulent organisms be a plausible cause for symptomatic disc degeneration? A systematic review". Spine. 40 (10): E587–92. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000832. PMID 25955094.

- Chen Z, Cao P, Zhou Z, Yuan Y, Jiao Y, Zheng Y (2016). "Overview: the role of Propionibacterium acnes in nonpyogenic intervertebral discs". Int Orthop (Review). 40 (6): 1291–8. doi:10.1007/s00264-016-3115-5. PMID 26820744.

- Parks, Edward (2017). Practical Office Orthopedics. [New York, N.Y.]: McGraw-Hill. pp. Chapter 6: Low Back Pain. ISBN 9781259642876. OCLC 986993775.

- Halpern, Casey H. (2015). Schwartz's Principles of Surgery. Grady, M. Sean (Tenth ed.). [New York]: McGraw-Hill. pp. Chapter 42: Neurosurgery. ISBN 9780071800921. OCLC 892490454.

- LeBlond, Richard F. (2015). DeGowin's Diagnostic Examination. Brown, Donald D., Suneja, Manish, Szot, Joseph F. (Tenth ed.). New York. pp. Chapter 13: The Spine, Pelvis, and Extremities. ISBN 9780071814478. OCLC 876336892.

- Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Peul WC (June 2007). "Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica". BMJ. 334 (7607): 1313–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.39223.428495.BE. PMC 1895638. PMID 17585160.

- Speed C (May 2004). "Low back pain". BMJ. 328 (7448): 1119–21. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7448.1119. PMC 406328. PMID 15130982.

- Gregory DS, Seto CK, Wortley GC, Shugart CM (October 2008). "Acute lumbar disk pain: navigating evaluation and treatment choices". Am Fam Physician. 78 (7): 835–42. PMID 18841731.

- Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, et al. (2007). "Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster". Clin. Infect. Dis. 44 Suppl 1: S1–26. doi:10.1086/510206. PMID 17143845.

- Shapiro ED (May 2014). "Clinical practice. Lyme disease" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (18): 1724–1731. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1314325. PMC 4487875. PMID 24785207. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2016.

- "Lyme Disease Data and surveillance". Lyme Disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019-02-05. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- "Lyme Disease risk areas map". Risk of Lyme disease to Canadians. Government of Canada. 2015-01-27. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- Ogrinc K, Lusa L, Lotrič-Furlan S, Bogovič P, Stupica D, Cerar T, Ružić-Sabljić E, Strle F (Aug 2016). "Course and outcome of early European Lyme neuroborreliosis (Bannwarth syndrome): clinical and laboratory findings". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 63 (3): 346–53. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw299. PMID 27161773.

- Lewis RA, Williams NH, Sutton AJ, Burton K, Din NU, Matar HE, Hendry M, Phillips CJ, Nafees S, Fitzsimmons D, Rickard I, Wilkinson C (June 2015). "Comparative clinical effectiveness of management strategies for sciatica: systematic review and network meta-analyses" (PDF). Spine J. 15 (6): 1461–77. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2013.08.049. PMID 24412033.

- Casey E (February 2011). "Natural history of radiculopathy". Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 22 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2010.10.001. PMID 21292142.

- Dahm, Kristin Thuve; Brurberg, Kjetil G.; Jamtvedt, Gro; Hagen, Kåre Birger (2010-06-16). "Advice to rest in bed versus advice to stay active for acute low-back pain and sciatica". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD007612. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007612.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 20556780.

- Basson, Annalie; Olivier, Benita; Ellis, Richard; Coppieters, Michel; Stewart, Aimee; Mudzi, Witness (2017-08-31). "The Effectiveness of Neural Mobilization for Neuromusculoskeletal Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 47 (9): 593–615. doi:10.2519/jospt.2017.7117. PMID 28704626.

The majority of studies had a high risk of bias

- Pinto RZ, Maher CG, Ferreira ML, Ferreira PH, Hancock M, Oliveira VC, et al. (February 2012). "Drugs for relief of pain in patients with sciatica: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 344: e497. doi:10.1136/bmj.e497. PMC 3278391. PMID 22331277.

- Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, Day RO, Pinheiro MB, Ferreira ML (July 2017). "Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for spinal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76 (7): 1269–1278. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210597. PMID 28153830.

- Rasmussen-Barr E, Held U, Grooten WJ, Roelofs PD, Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Wertli MM (October 2016). "Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for sciatica". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 10: CD012382. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012382. PMC 6461200. PMID 27743405.

- Waseem Z, Boulias C, Gordon A, Ismail F, Sheean G, Furlan AD (January 2011). "Botulinum toxin injections for low-back pain and sciatica". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD008257. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008257.pub2. PMID 21249702.

- Balagué F, Piguet V, Dudler J (2012). "Steroids for LBP - from rationale to inconvenient truth". Swiss Med Wkly. 142: w13566. doi:10.4414/smw.2012.13566. PMID 22495738.

- Chou R, Hashimoto R, Friedly J, Fu R, Bougatsos C, Dana T, Sullivan SD, Jarvik J (September 2015). "Epidural Corticosteroid Injections for Radiculopathy and Spinal Stenosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Ann. Intern. Med. 163 (5): 373–81. doi:10.7326/M15-0934. PMID 26302454.

- Fernandez M, Ferreira ML, Refshauge KM, Hartvigsen J, Silva IR, Maher CG, Koes BW, Ferreira PH (November 2016). "Surgery or physical activity in the management of sciatica: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Eur Spine J. 25 (11): 3495–3512. doi:10.1007/s00586-015-4148-y. PMID 26210309.

- Leininger B, Bronfort G, Evans R, Reiter T (February 2011). "Spinal manipulation or mobilization for radiculopathy: a systematic review". Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 22 (1): 105–25. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2010.11.002. PMID 21292148.

- Tamburrelli FC, Genitiempo M, Logroscino CA (May 2011). "Cauda equina syndrome and spine manipulation: case report and review of the literature". Eur Spine J. 20 Suppl 1: S128–31. doi:10.1007/s00586-011-1745-2. PMC 3087049. PMID 21404036.

- WHO guidelines on basic training and safety in chiropractic. "2.1 Absolute contraindications to spinal manipulative therapy", p. 21. Archived 2008-02-27 at the Wayback Machine WHO

- Wilkinson, C.; Chakraverty, R.; Rickard, I.; Hendry, M.; Nafees, S.; Burton, K.; Sutton, A.; Jones, M.; Phillips, C. (November 2011). Background. NIHR Journals Library.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |