Radioisotope renography

Radioisotope renography is a form of medical imaging of the kidneys that uses radiolabelling. A renogram, which may also be known as a MAG3 scan, allows a nuclear medicine physician or a radiologist to visualize the kidneys and learn more about how they are functioning.[1] MAG3 is an acronym for mercapto acetyl tri glycine, a compound that is chelated with a radioactive element – technetium-99m.

| Radioisotope renography | |

|---|---|

| Medical diagnostics | |

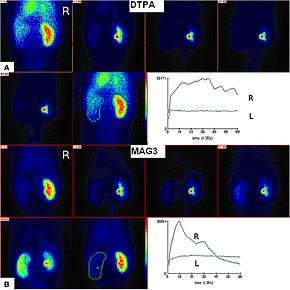

Renal imaging using 99mTc-DTPA and 99mTc-MAG3 with renographic curves | |

| ICD-9-CM | 92.03 |

| MeSH | D011866 |

| OPS-301 code | 3-706 |

The two most common radiolabelled pharmaceutical agents used are Tc99m-MAG3 (MAG3 is also called mercaptoacetyltriglycine or mertiatide) and Tc99m-DTPA (diethylenetriaminepentacetate). Some other radiolabelled pharmaceuticals are EC (Ethylenedicysteine) and 131-iodine labelled OIH (ortho-iodohippurate).[2]

Scan procedure

After injection into the venous system, the compound is excreted by the kidneys and its progress through the renal system can be tracked with a gamma camera. A series of images are taken at regular intervals. Processing then involves drawing a region of interest (ROI) around both kidneys, and a computer program produces a graph of radioactivity inside the kidney with time, representing the quantity of tracer, from the number of counts measured inside in each image (representing a different time point).[3]

If the kidney is not getting blood for example, it will not be viewed at all, even if it looks structurally normal in medical ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging. If the kidney is getting blood, but there is an obstruction inferior to the kidney in the bladder or ureters, the radioisotope will not pass beyond the level of the obstruction, whereas if there is a partial obstruction then there is a delayed transit time for the MAG3 to pass.[4] More information can be gathered by calculating time activity curves; with normal kidney perfusion, peak activity should be observed after 3–5 minutes.[5] The relative quantitative information gives the differential function between each kidney's filtration activity.

Tracers

MAG3 is preferred over Tc-99m-DTPA in neonates, patients with impaired function, and patients with suspected obstruction, due to its more efficient extraction.[2][6][7] The MAG3 clearance is highly correlated with the effective renal plasma flow (ERPF), and the MAG3 clearance can be used as an independent measure of kidney function.[8] After intravenous administration, about 40-50% of the MAG3 in the blood is extracted by the proximal tubules with each pass through the kidneys; the proximal tubules then secrete the MAG3 into the tubular lumen.[9]

Tc-99m-DTPA is filtered by the glomerulus and may be used to measure the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (in a separate test), making it theoretically the best (most accurate) choice for kidney function imaging.[10] The extraction fraction of DTPA is approximately 20%, less than half that of MAG3.[9] DTPA is the second most commonly used renal radiopharmaceutical in the United States.[11]

Clinical use

The technique is very useful in evaluating the functioning of kidneys. Radioisotopes can differentiate between passive dilatation and obstruction. It is widely used before renal transplantation to assess the vascularity of the kidney to be transplanted and with a test dose of captopril to highlight possible renal artery stenosis in the donor's other kidney,[12] and later the performance of the transplant.[13][14]

The use of the test to identify reduced kidney function after test doses of captopril (an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor drug) has also been used to identify the cause of hypertension in patients with renal failure.[15][16] Initially there was uncertainty as to the usefulness,[17] or best test parameter to identify renal artery stenosis, the eventual consensus was that the distinctive finding is of alteration in the differential function.[18]

History

In 1986, MAG3 was developed at the University of Utah by Dr. Alan R. Fritzberg, Dr. Sudhakar Kasina, and Dr. Dennis Eshima.[19] The drug underwent clinical trials in 1987 [20] and passed Phase III testing in 1988.[21]

99mTc-MAG3 has replaced the older iodine-131 orthoiodohippurate or I131-Hippuran because of better quality imaging regardless of the level of kidney function,[22] and with the benefit of being able to administer lower radiation dosages.[21]

See also

References

- "The Renogram". British Nuclear Medicine Society. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- Taylor, A. T. (18 February 2014). "Radionuclides in Nephrourology, Part 1: Radiopharmaceuticals, Quality Control, and Quantitative Indices". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 55 (4): 608–615. doi:10.2967/jnumed.113.133447. PMC 4061739. PMID 24549283.

- Elgazzar, Abdelhamid H. (2011-05-10). A Concise Guide to Nuclear Medicine. Springer. p. 15. ISBN 9783642194269.

- González A, Jover L, Mairal LI, Martin-Comin J, Puchal R (1994). "Evaluation of obstructed kidneys by discriminant analysis of 99mTc-MAG3 renograms". Nuklearmedizin. 33 (6): 244–7. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1629712. PMID 7854921.

- Sandler, Martin P. (2003). Diagnostic Nuclear Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 868. ISBN 9780781732529.

- Gordon, Isky; Piepsz, Amy; Sixt, Rune (19 April 2011). "Guidelines for standard and diuretic renogram in children". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 38 (6): 1175–1188. doi:10.1007/s00259-011-1811-3. PMID 21503762.

- Shulkin, B. L.; Mandell, G. A.; Cooper, J. A.; Leonard, J. C.; Majd, M.; Parisi, M. T.; Sfakianakis, G. N.; Balon, H. R.; Donohoe, K. J. (14 August 2008). "Procedure Guideline for Diuretic Renography in Children 3.0". Journal of Nuclear Medicine Technology. 36 (3): 162–168. doi:10.2967/jnmt.108.056622. PMID 18765635.

- Biersack, Hans-Jürgen; Freeman, Leonard M. (2008-01-03). Clinical Nuclear Medicine. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 173. ISBN 9783540280262.

- Alazraki, Andrew Taylor, David M. Schuster, Naomi (2006). "The Genitourinary System" (PDF). A clinician's guide to nuclear medicine (2nd ed.). Reston, VA: Society of Nuclear Medicine. p. 49. ISBN 9780972647878.

- Durand, E; Prigent, A (December 2002). "The basics of renal imaging and function studies". The Quarterly Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 46 (4): 249–67. PMID 12411866.

- Archer, K. D.; Bolus, N. E. (27 October 2016). "Survey on the Use of Nuclear Renal Imaging in the United States". Journal of Nuclear Medicine Technology. 44 (4): 223–226. doi:10.2967/jnmt.116.181339. PMID 27789752.

- Dubovsky EV, Diethelm AG, Keller F, Russell CD (1992). "Renal transplant hypertension caused by iliac artery stenosis" (PDF). J. Nucl. Med. 33 (6): 1178–80. PMID 1534577.

- Kramer W, Baum RP, Scheuermann E, Hör G, Jonas D (1993). "[Follow-up after kidney transplantation. Sequential functional scintigraphy with technetium-99m-DTPA or technetium-99m-MAG3]". Urologe A (in German). 32 (2): 115–20. PMID 8475609.

- Li Y, Russell CD, Palmer-Lawrence J, Dubovsky EV (1994). "Quantitation of renal parenchymal retention of technetium-99m-MAG3 in renal transplants". J. Nucl. Med. 35 (5): 846–50. PMID 8176469.

- Datseris IE, Bomanji JB, Brown EA, et al. (1994). "Captopril renal scintigraphy in patients with hypertension and chronic renal failure". J. Nucl. Med. 35 (2): 251–4. PMID 8294993.

- Kahn D, Ben-Haim S, Bushnell DL, Madsen MT, Kirchner PT (1994). "Captopril-enhanced 99Tcm-MAG3 renal scintigraphy in subjects with suspected renovascular hypertension". Nucl Med Commun. 15 (7): 515–28. doi:10.1097/00006231-199407000-00005. PMID 7970428.

- Schreij G, van Es PN, van Kroonenburgh MJ, Kemerink GJ, Heidendal GA, de Leeuw PW (1996). "Baseline and postcaptopril renal blood flow measurements in hypertensives suspected of renal artery stenosis". J. Nucl. Med. 37 (10): 1652–5. PMID 8862302.

- Roccatello D, Picciotto G (1997). "Captopril-enhanced scintigraphy using the method of the expected renogram: improved detection of patients with renin-dependent hypertension due to functionally significant renal artery stenosis" (PDF). Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 12 (10): 2081–6. doi:10.1093/ndt/12.10.2081. PMID 9351069.

- Fritzberg AR, Kasina S, Eshima D, Johnson DL (1986). "Synthesis and biological evaluation of technetium-99m MAG3 as a hippuran replacement". J. Nucl. Med. 27 (1): 111–6. PMID 2934521.

- Taylor A, Eshima D, Alazraki N (1987). "99mTc-MAG3, a new renal imaging agent: preliminary results in patients". Eur J Nucl Med. 12 (10): 510–4. doi:10.1007/BF00620476. PMID 2952506.

- Al-Nahhas AA, Jafri RA, Britton KE, et al. (1988). "Clinical experience with 99mTc-MAG3, mercaptoacetyltriglycine, and a comparison with 99mTc-DTPA". Eur J Nucl Med. 14 (9–10): 453–62. doi:10.1007/BF00252388. PMID 2975219.

- Taylor A, Eshima D, Christian PE, Milton W (1987). "Evaluation of Tc-99m mercaptoacetyltriglycine in patients with impaired renal function". Radiology. 162 (2): 365–70. doi:10.1148/radiology.162.2.2948212. PMID 2948212.