Pupillary light reflex

The pupillary light reflex (PLR) or photopupillary reflex is a reflex that controls the diameter of the pupil, in response to the intensity (luminance) of light that falls on the retinal ganglion cells of the retina in the back of the eye, thereby assisting in adaptation of vision to various levels of lightness/darkness. A greater intensity of light causes the pupil to constrict (miosis/myosis; thereby allowing less light in), whereas a lower intensity of light causes the pupil to dilate (mydriasis, expansion; thereby allowing more light in). Thus, the pupillary light reflex regulates the intensity of light entering the eye.[1] Light shone into one eye will cause both pupils to constrict.

Terminology

The Pupil is the dark circular opening in the center of the iris and is where light enters the eye. By analogy with a camera, the pupil is equivalent to aperture, whereas the iris is equivalent to the diaphragm. It may be helpful to consider the Pupillary reflex as an 'Iris' reflex, as the iris sphincter and dilator muscles are what can be seen responding to ambient light[2]. Whereas, the pupil is the passive opening formed by the active iris. Pupillary reflex is synonymous with pupillary response, which may be pupillary constriction or dilation. Pupillary reflex is conceptually linked to the side (left or right) of the reacting pupil, and not to the side from which light stimulation originates. Left pupillary reflex refers to the response of the left pupil to light, regardless of which eye is exposed to a light source. Right pupillary reflex means reaction of the right pupil, whether light is shone into the left eye, right eye, or both eyes. When light is shone into only one eye and not the other, it is normal for both pupils to constrict simultaneously. The terms direct and consensual refers to the side where the light source comes from, relative to the side of the reacting pupil. A direct pupillary reflex is pupillary response to light that enters the ipsilateral (same) eye. A consensual pupillary reflex is response of a pupil to light that enters the contralateral (opposite) eye. Thus there are four types of pupillary light reflexes, based on this terminology of absolute (left versus right) and relative (same side versus opposite side) laterality:

- Left direct pupillary reflex is the left pupil's response to light entering the left eye, the ipsilateral eye.

- Left consensual pupillary reflex is the left pupil's indirect response to light entering the right eye, the contralateral eye.

- Right direct pupillary reflex is the right pupil's response to light entering the right eye, the ipsilateral eye.

- Right consensual pupillary reflex is the right pupil's indirect response to light entering the left eye, the contralateral eye.

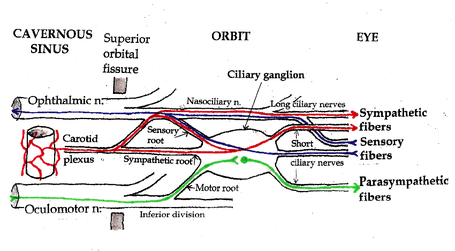

Neural pathway anatomy

The pupillary light reflex neural pathway on each side has an afferent limb and two efferent limbs. The afferent limb has nerve fibers running within the optic nerve (CN II). Each efferent limb has nerve fibers running along the oculomotor nerve (CN III). The afferent limb carries sensory input. Anatomically, the afferent limb consists of the retina, the optic nerve, and the pretectal nucleus in the midbrain, at level of superior colliculus. Ganglion cells of the retina project fibers through the optic nerve to the ipsilateral pretectal nucleus. The efferent limb is the pupillary motor output from the pretectal nucleus to the ciliary sphincter muscle of the iris. The pretectal nucleus projects crossed and uncrossed fibers to the ipsilateral and contralateral Edinger-Westphal nuclei, which are also located in the midbrain. Each Edinger-Westphal nucleus gives rise to preganglionic parasympathetic fibers which exit with CN III and synapse with postganglionic parasympathetic neurons in the ciliary ganglion. Postganglionic nerve fibers leave the ciliary ganglion to innervate the ciliary sphincter.[3] Each afferent limb has two efferent limbs, one ipsilateral and one contralateral. The ipsilateral efferent limb transmits nerve signals for direct light reflex of the ipsilateral pupil. The contralateral efferent limb causes consensual light reflex of the contralateral pupil.

Types of neurons

The optic nerve, or more precisely, the photosensitive ganglion cells through the retinohypothalamic tract, is responsible for the afferent limb of the pupillary reflex; it senses the incoming light. The oculomotor nerve is responsible for the efferent limb of the pupillary reflex; it drives the iris muscles that constrict the pupil.[1]

- Retina: The pupillary reflex pathway begins with the photosensitive retinal ganglion cells, which convey information via the optic nerve, the most peripheral, distal, portion of which is the optic disc. Some axons of the optic nerve connect to the pretectal nucleus of the upper midbrain instead of the cells of the lateral geniculate nucleus (which project to the primary visual cortex). These intrinsic photosensitive ganglion cells are also referred to as melanopsin-containing cells, and they influence circadian rhythms as well as the pupillary light reflex.

- Pretectal nuclei: From the neuronal cell bodies in some of the pretectal nuclei, axons synapse on (connect to) neurons in the Edinger-Westphal nucleus. Those neurons are the preganglionic cells with axons that run in the oculomotor nerves to the ciliary ganglia.

- Edinger-Westphal nuclei: Parasympathetic neuronal axons in the oculomotor nerve synapse on ciliary ganglion neurons.

- Ciliary ganglia: Short post-ganglionic ciliary nerves leave the ciliary ganglion to innervate the Iris sphincter muscle of the iris.[1]

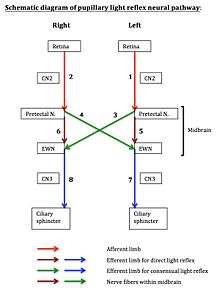

Schematic

Referring to the neural pathway schematic diagram, the entire pupillary light reflex system can be visualized as having eight neural segments, numbered 1 through 8. Odd-numbered segments 1, 3, 5, and 7 are on the left. Even-numbered segments 2, 4, 6, and 8 are on the right. Segments 1 and 2 each includes both the retina and the optic nerve (cranial Nerve #2). Segments 3 and 4 are nerve fibers that cross from the pretectal nucleus on one side to the Edinger-Westphal nucleus on the contralateral side. Segments 5 and 6 are fibers that connect the pretectal nucleus on one side to the Edinger-Westphal nucleus on the same side. Segments 3, 4, 5, and 6 are all located within a compact region within the midbrain. Segments 7 and 8 each contains parasympathetic fibers that courses from the Edinger-Westphal nucleus, through the ciliary ganglion, along the oculomotor nerve (cranial nerve #3), to the ciliary sphincter, the muscular structure within the iris.

- Left direct light reflex involves neural segments 1, 5, and 7. Segment 1 is the afferent limb, which includes the retina and optic nerve. Segments 5 and 7 form the efferent limb.

- Left consensual light reflex involves neural segments 2, 4, and 7. Segment 2 is the afferent limb. Segments 4 and 7 form the efferent limb.

- Right direct light reflex involves neural segments 2, 6, and 8. Segment 2 is the afferent limb. Segments 6 and 8 form the efferent limb.

- Right consensual light reflex involves neural segments 1, 3, and 8. Segment 1 is the afferent limb. Segments 3 and 8 form the efferent limb.

The diagram may assist in localizing lesion within the pupillary reflex system by process of elimination, using light reflex testing results obtained by clinical examination.

Clinical significance

Pupillary light reflex provides a useful diagnostic tool for testing the integrity of the sensory and motor functions of the eye.[1] Emergency physicians routinely test pupillary light reflex to assess brain stem function. Abnormal pupillary reflex can be found in optic nerve injury, oculomotor nerve damage, brain stem lesion (including brain stem death), and depressant drugs, such as barbiturates.[4][5] Examples are provided as below:

- Optic nerve damage on the left (e.g. transection of left optic nerve, CN II, somewhere between retina and optic chiasma, therefore damaging the left afferent limb, leaving the rest of the pupillary light reflex neural pathway on both sides intact) will have the following clinical findings:

- The left direct reflex is lost. When the left eye is stimulated by light, neither pupils constrict. Afferent signals from the left eye cannot pass through the transected left optic nerve to reach the intact efferent limb on the left.

- The right consensual reflex is lost. When left eye is stimulated by light, afferent signals from the left eye cannot pass through the transected left optic nerve to reach the intact efferent limb on the right.

- The right direct reflex is intact. Direct light reflex of right pupil involves the right optic nerve and right oculomotor nerve, which are both intact.

- The left consensual reflex is intact. Consensual light reflex of left pupil involves the right optic nerve and left oculomotor nerve, which are both undamaged.

- Oculomotor nerve damage on the left (e.g. transection of left oculomotor nerve, CN III, therefore damaging the left efferent limb) will have the following clinical findings:

- The left direct reflex is lost. When the left eye is stimulated by light, left pupil does not constrict, because the efferent signals cannot pass from midbrain, through left CN III, to the left pupillary sphincter.

- The right consensual reflex is intact. When the left eye is stimulated by light, the right pupil constricts, because the afferent limb on the left and the efferent limb on the right are both intact.

- The right direct reflex is intact. When light is shone into right eye, right pupil constricts. Direct reflex of the right pupil is unaffected, The right afferent limb, right CN II, and the right efferent limb, right CN III, are both intact.

- The left consensual reflex is lost. When the right eye is stimulated by light, left pupil does not constrict consensually. Right afferent limb is intact, but left efferent limb, left CN III, is damaged.

Lesion localization example

For example, in a person with abnormal left direct reflex and abnormal right consensual reflex (with normal left consensual and normal right direct reflexes), which would produce a left Marcus Gunn pupil, or what is called afferent pupillary defect, by physical examination:

- Left consensual reflex is normal, therefore segments 2, 4, and 7 are normal. Lesion is not located in any of these segments.

- Right direct reflex is normal, therefore segments 2, 6, and 8 are normal. Combining with earlier normals, segments 2, 4, 6, 7, and 8 are all normal.

- Remaining segments where lesion may be located are segments 1, 3, and 5. Possible combinations and permutations are: (a) segment 1 only, (b) segment 3 only, (c) segment 5 only, (d) combination of segments 1 and 3, (e) combination of segments 1 and 5, (f) combination of segments 3 and 5, and (g) combination of segments 1, 3, and 5.

- Options (b) and (c) are eliminated because isolated lesion in segment 3 alone or in segment 5 alone cannot produce the light reflex abnormalities in question.

- A single lesion anywhere along segment 1, the left afferent limb, which includes the left retina, left optic nerve, and left pretectal nucleus, can produce the light reflex abnormalities observed. Examples of segment 1 pathologies include left optic neuritis (inflammation or infection of the left optic nerve), detachment of left retina, and an isolated small stroke involving only the left pretectal nucleus. Therefore, options (a), (d), (e), (f), and (g) are possible.

- A combined lesion in segments 3 and 5 as cause of defect is very unlikely. Microscopically precise strokes in the midbrain, involving the left pretectal nucleus, bilateral Edinger-Westphal nuclei, and their interconnecting fibers, could theoretically produce this result. Furthermore, segment 4 shares the same anatomical space in the midbrain as segment 3, therefore segment 4 will likely be affected if segment 3 is damaged. In this setting, it is very unlikely that left consensual reflex, which requires an intact segment 4, would be preserved. Therefore, options (d), (f), and (g), which all includes segment 3, are eliminated. Remaining possible options are (a) and (e).

- Based on the above reasoning, the lesion must involve segment 1. Damage to segment 5 may accompany a segment 1 lesion, but is unnecessary for producing the abnormal light reflex results in this case. Option (e) involves a combined lesion of segments 1 and 5. Multiple sclerosis, which often affects multiple neurologic sites simultaneously, could potentially cause this combination lesion. In all probability, option (a) is the answer. Neuro-imaging, such as MRI scan, would be useful for confirmation of clinical findings.

Cognitive influences

The pupillary response to light is not purely reflexive, but is modulated by cognitive factors, such as attention, awareness, and the way visual input is interpreted. For example, if a bright stimulus is presented to one eye, and a dark stimulus to the other eye, perception alternates between the two eyes (i.e., binocular rivalry): Sometimes the dark stimulus is perceived, sometimes the bright stimulus, but never both at the same time. Using this technique, it has been shown the pupil is smaller when a bright stimulus dominates awareness, relative to when a dark stimulus dominates awareness.[6][7] This shows that the pupillary light reflex is modulated by visual awareness. Similarly, it has been shown that the pupil constricts when you covertly (i.e., without looking at) pay attention to a bright stimulus, compared to a dark stimulus, even when visual input is identical.[8][9][10] Moreover, the magnitude of the pupillary light reflex following a distracting probe is strongly correlated with the extent to which the probe captures visual attention and interferes with task performance.[11] This shows that the pupillary light reflex is modulated by visual attention and trial-by-trial variation in visual attention. Finally, a picture that is subjectively perceived as bright (e.g. a picture of the sun), elicits a stronger pupillary constriction than an image that is perceived as less bright (e.g. a picture of an indoor scene), even when the objective brightness of both images is equal.[12][13] This shows that the pupillary light reflex is modulated by subjective (as opposed to objective) brightness.

Mathematical model

Pupillary light reflex is modeled as a physiologically-based non-linear delay differential equation that describes the changes in the pupil diameter as a function of the environment lighting:[14]

where is the pupil diameter measured in millimeters and is the luminous intensity reaching the retina in a time , which can be described as : luminance reaching the eye in lumens/mm2 times the pupil area in mm2. is the pupillary latency, a time delay between the instant in which the light pulse reaches the retina and the beginning of iridal reaction due nerve transmission, neuro-muscular excitation and activation delays. , and are the derivatives for the function, pupil diameter and time .

Since the pupil constriction velocity is approximately 3 times faster than (re)dilation velocity,[15] different step sizes in the numerical solver simulation must be used:

where and are respectively the for constriction and dilation measured in milliseconds, and are respectively the current and previous simulation times (times since the simulation started) measured in milliseconds, is a constant that affects the constriction/dilation velocity and varies among individuals. The higher the value, the smaller the time step used in the simulation and, consequently, the smaller the pupil constriction/dilation velocity.

In order to improve the realism of the resulting simulations, the hippus effect can be approximated by adding small random variations to the environment light (in the range 0.05–0.3 Hz).[16]

See also

References

- Purves, Dale, George J. Augustine, David Fitzpatrick, William C. Hall, Anthony-Samuel LaMantia, James O. McNamara, and Leonard E. White (2008). Neuroscience. 4th ed. Sinauer Associates. pp. 290–1. ISBN 978-0-87893-697-7.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Hall, Charlotte; Chilcott, Robert (2018). "Eyeing up the Future of the Pupillary Light Reflex in Neurodiagnostics". Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). Diagnostics — Open Access Journal. 8 (1): 19. doi:10.3390/diagnostics8010019. PMC 5872002. PMID 29534018.

- Kaufman, Paul L.; Levin, Leonard A.; Alm, Albert (2011). Adler's Physiology of the Eye. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 508. ISBN 978-0-323-05714-1.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537180/

- Ciuffreda, K. J.; Joshi, N. R.; Truong, J. Q. (2017). "Understanding the effects of mild traumatic brain injury on the pupillary light reflex". Concussion. 2 (3): CNC36. doi:10.2217/cnc-2016-0029. PMC 6094691. PMID 30202579.

- Harms, H. (1937). "Ort und Wesen der Bildhemmung bei Schielenden". Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 138 (1): 149–210. doi:10.1007/BF01854538.

- Naber M., Frassle, S. Einhaüser W. (2011). "Perceptual rivalry: Reflexes reveal the gradual nature of visual awareness". PLoS ONE. 6 (6): e2011. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020910. PMC 3109001. PMID 21677786.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Binda P.; Pereverzeva M.; Murray S.O. (2013). "Attention to bright surfaces enhances the pupillary light reflex". Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (5): 2199–2204. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.3440-12.2013. PMC 6619119. PMID 23365255.

- Mathôt S., van der Linden, L. Grainger, J. Vitu, F. (2013). "The pupillary response to light reflects the focus of covert visual attention". PLoS ONE. 8 (10): e78168. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078168. PMC 3812139. PMID 24205144.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Mathôt S., Dalmaijer E., Grainger J., Van der Stigchel, S. (2014). "The pupillary light response reflects exogenous attention and inhibition of return" (PDF). Journal of Vision. 14 (14): e7. doi:10.1167/14.14.7. PMID 25761284.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Ebitz R.; Pearson J.; Platt M. (2014). "Pupil size and social vigilance in rhesus macaques". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 8 (100): 100. doi:10.3389/fnins.2014.00100. PMC 4018547. PMID 24834026.

- Binda P.; Pereverzeva M.; Murray S.O. (2013). "Pupil constrictions to photographs of the sun". Journal of Vision. 13 (6): e8. doi:10.1167/13.6.8. PMID 23685391.

- Laeng B.; Endestad T. (2012). "Bright illusions reduce the eye's pupil". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (6): 2162–2167. doi:10.1073/pnas.1118298109. PMC 3277565. PMID 22308422.

- Pamplona, Vitor F.; Oliveira, Manuel M.; Baranoski, Gladimir V. G. (1 August 2009). "Photorealistic models for pupil light reflex and iridal pattern deformation" (PDF). ACM Transactions on Graphics. 28 (4): 1–12. doi:10.1145/1559755.1559763. hdl:10183/15309.

- Ellis, C. J. (1981). "The pupillary light reflex in normal subjects". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 65 (11): 754–759. doi:10.1136/bjo.65.11.754. PMC 1039657. PMID 7326222.

- Stark, L (August 1963). "Stability, Oscillations, and Noise in the Human Pupil Servomechanism". Boletin del Instituto de Estudios Medicos y Biologicos, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. 21: 201–22. PMID 14122256.

External links

- Animation of pupillary light reflex

- Reflex,+Pupillary at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- A pupil examination simulator, demonstrating the changes in pupil reactions for various nerve lesions.