Primary biliary cholangitis

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), previously known as primary biliary cirrhosis, is an autoimmune disease of the liver.[1][2][3] It results from a slow, progressive destruction of the small bile ducts of the liver, causing bile and other toxins to build up in the liver, a condition called cholestasis. Further slow damage to the liver tissue can lead to scarring, fibrosis, and eventually cirrhosis.

| Primary biliary cholangitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Primary biliary cirrhosis |

| |

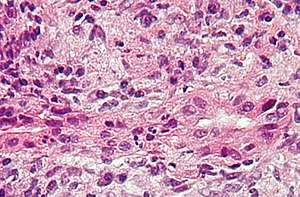

| Micrograph of PBC showing bile duct inflammation and injury. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Cholestasis, pruritus, fatigue |

| Complications | Cirrhosis, hepatic failure, portal hypertension |

| Usual onset | Usually middle-aged women |

| Causes | Autoimmune |

| Diagnostic method | Anti-mitochondrial antibodies, liver biopsy |

Common symptoms are tiredness, itching and, in more advanced cases, jaundice. In early cases, there may only be changes in blood tests.[4]

PBC is a relatively rare disease, affecting up to 1 in 3–4,000 people.[5][6] It is much more common in women, with a sex ratio of at least 9:1 female to male.[1]

The condition has been recognised since at least 1851 and was named "primary biliary cirrhosis" in 1949.[7] Because cirrhosis is a feature only of advanced disease, a change of its name to "primary biliary cholangitis" was proposed by patient advocacy groups in 2014.[8][9]

Signs and symptoms

People with PBC experience fatigue (80 percent) that leads to sleepiness during the daytime; more than half of those have severe fatigue. Dry skin and dry eyes are also common. Itching (pruritus) occurs in 20–70 percent.[4] People with more severe PBC may have jaundice (yellowing of the eyes and skin).[4] PBC impairs bone density and there is an increased risk of fracture.[4] Xanthelasma (skin lesions around the eyes) or other xanthoma may be present as a result of increased cholesterol levels.[10]

PBC can eventually progress to cirrhosis of the liver. This in turn may lead to a number of symptoms or complications:

- Fluid retention in the abdomen (ascites) in more advanced disease

- Enlarged spleen in more advanced disease

- Oesophageal varices in more advanced disease

- Hepatic encephalopathy, including coma in extreme cases in more advanced disease.

People with PBC may also sometimes have the findings of an associated extrahepatic autoimmune disorder such as rheumatoid arthritis or Sjögren's syndrome (in up to 80 percent of cases).[10][11]

Causes

PBC has an immunological basis, and is classified as an autoimmune disorder.[12] It results from a slow, progressive destruction of the small bile ducts of the liver, with the intralobular ducts and the Canals of Hering (intrahepatic ductules) being affected early in the disease.[13] This progresses to the development of fibrosis, cholestasis and, in some people, cirrhosis.[2]

Most people with PBC (>90 percent) have anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMAs) against pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC-E2), an enzyme complex that is found in the mitochondria.[1] People who are negative for AMAs are usually found to be positive when more sensitive methods of detection are used.[14]

People with PBC may also have been diagnosed with another autoimmune disease, such as a rheumatological, endocrinological, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, or dermatological condition, suggesting shared genetic and immune abnormalities.[11] Common associations include Sjögren's syndrome, systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, hypothyroidism and gluten sensitive enteropathy.[11][15][16][17]

A genetic predisposition to disease has been thought to be important for some time. Evidence for this includes cases of PBC in family members, identical twins both having the condition (concordance), and clustering of PBC with other autoimmune diseases.[12] In 2009, a Canadian-led group of investigators reported in the New England Journal of Medicine results from the first PBC genome-wide association study.[18][19] This research revealed parts of the IL12 signaling cascade, particularly IL12A and IL12RB2 polymorphisms, to be important in the aetiology of the disease in addition to the HLA region. In 2012, two independent PBC association studies increased the total number of genomic regions associated to 26, implicating many genes involved in cytokine regulation such as TYK2, SH2B3 and TNFSF11.[20][21]

A study of over 2000 patients identified a gene - POGLUT1 - that appeared to be associated with this condition.[22] Earlier studies have also suggested that this gene may be involved. The implicated protein is an endoplasmic reticulum O-glucosyltransferase.

An environmental Gram negative alphabacterium — Novosphingobium aromaticivorans[23] has been associated with this disease with several reports suggesting an aetiological role for this organism.[24][25][26] The mechanism appears to be a cross reaction between the proteins of the bacterium and the mitochondrial proteins of the liver cells.[27] The gene encoding CD101 may also play a role in host susceptibility to this disease.[28]

There is a failure of immune tolerance against the mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC-E2),[2] and this may also be the case with other proteins, including the gp210 and p62 nuclear pore proteins. Gp210 has increased expression in the bile duct of anti-gp210 positive patients, and these proteins may be associated with prognosis.[29]

Diagnosis

To diagnose PBC, it needs to be distinguished from other conditions with similar symptoms, such as autoimmune hepatitis or primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC).

- Abnormalities in liver enzyme tests are usually present and elevated gamma-glutamyl transferase and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) are found in early disease.[10] Elevations in bilirubin occur in advanced disease.

- Antimitochondrial antibodies are the characteristic serological marker for PBC, being found in 90-95 percent of patients and only 1 percent of controls. PBC patients have AMA against pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC-E2), an enzyme complex that is found in the mitochondria.[10] Those people who are AMA negative but with disease similar to PBC have been found to have AMAs when more sensitive detection methods are employed.[14]

- Other auto-antibodies may be present:

- Antinuclear antibody measurements are not diagnostic for PBC because they are not specific, but may have a role in prognosis.

- Anti-glycoprotein-210 antibodies, and to a lesser degree anti-p62 antibodies, correlate with the disease's progression toward end stage liver failure. Anti-gp210 antibodies are found in 47 percent of PBC patients.[30][31]

- Anti-centromere antibodies often correlate with developing portal hypertension.[32]

- Anti-np62[33] and anti-sp100 are also found in association with PBC.

- Abdominal ultrasound, MR scanning (MRCP) or a CT scan is usually performed to rule out blockage to the bile ducts. This may be needed if a condition causing secondary biliary cirrhosis, such as other biliary duct disease or gallstones, needs to be excluded. A liver biopsy may help, and if uncertainty remains as in some patients, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), an endoscopic investigation of the bile duct, may be performed.

Most patients can be diagnosed without invasive investigation, as the combination of anti-mitochondrial antibodies and typical (cholestatic) liver enzyme tests are considered diagnostic. However, a liver biopsy is needed to determine the stage of disease.

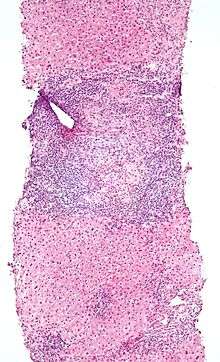

Low magnification micrograph of PBC. H&E stain.

Low magnification micrograph of PBC. H&E stain. Intermediate magnification micrograph of PBC showing bile duct inflammation and periductal granulomas. Liver biopsy. H&E stain.

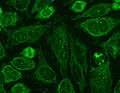

Intermediate magnification micrograph of PBC showing bile duct inflammation and periductal granulomas. Liver biopsy. H&E stain. Immunofluorescence staining pattern of sp100 antibodies (nuclear dots) and AMA.

Immunofluorescence staining pattern of sp100 antibodies (nuclear dots) and AMA.

Liver biopsy

On microscopic examination of liver biopsy specimens, PBC is characterized by interlobular bile duct destruction. These histopathologic findings in primary biliary cholangitis include the following:[34]

- Inflammation of the bile ducts, characterized by intraepithelial lymphocytes, and

- Periductal epithelioid granulomata.

Histopathology stages

- Stage 1 – Portal Stage: Normal sized triads; portal inflammation, subtle bile duct damage. Granulomas are often detected in this stage.

- Stage 2 – Periportal Stage: Enlarged triads; periportal fibrosis and/or inflammation. Typically characterized by the finding of a proliferation of small bile ducts.

- Stage 3 – Septal Stage: Active and/or passive fibrous septa.

- Stage 4 – Biliary Cirrhosis: Nodules present; garland or jigsaw puzzle pattern.

Treatment

There is no known cure, but medication may slow the progression so that a normal lifespan and quality of life may be attainable for many patients.[10][35][36]

- Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), marketed as Ursodiol and others, is the most frequently used treatment. It helps reduce the cholestasis and improves liver function tests. It has a minimal effect on symptoms and whether it improves outcomes is controversial.[37][10] A Cochrane review from 2012 did not show any significant benefits on important outcomes including mortality, liver transplantation or PBC symptoms, even if some biochemical and histological parameters were improved.[37]

- To relieve itching caused by bile acids in circulation, which are normally removed by the liver, cholestyramine (a bile acid sequestrant) may be prescribed to absorb bile acids in the gut and be eliminated, rather than re-enter the blood stream. Other drugs that do this include stanozolol, naltrexone and rifampicin.[35][36][38]

- Specific treatment for fatigue, which may be debilitating in some patients, is limited and undergoing trials.[39] Some studies indicate that Provigil (modafinil) may be effective without damaging the liver.[40] Though modafinil is no longer covered by patents, the limiting factor in its use in the U.S. is cost. The manufacturer, Cephalon, has made agreements with manufacturers of generic modafinil to provide payments in exchange for delaying their sale of modafinil.[41] The FTC has filed suit against Cephalon alleging anti-competitive behavior.[42]

- People with PBC may have poor lipid-dependent absorption of Vitamins A, D, E, K.[43] Appropriate supplementation is recommended when bilirubin is elevated.[10]

- People with PBC are at elevated risk of developing osteoporosis[44] and esophageal varices[45] as compared to the general population and others with liver disease. Screening and treatment of these complications is an important part of the management of PBC.

- As in all liver diseases, consumption of alcohol is contraindicated.

- In advanced cases, a liver transplant, if successful, results in a favorable prognosis.[46][47]

- The farnesoid X receptor agonist, obeticholic acid (marketed as Ocaliva), has been licensed by various regulatory authorities, including the United States Food and Drug Administration, as an orphan drug in an accelerated approval program. Obeticholic acid, which is a modified bile acid, produced a reduction in the level of the biomarker alkaline phosphatase, a surrogate endpoint for clinical benefit in PBC.[48] It is indicated for the treatment of PBC in combination with ursodeoxycholic acid in adults with an inadequate response to UDCA, or as monotherapy in adults unable to tolerate UDCA.[49] Additional studies are being undertaken to verify and describe clinical benefit.[50]

- Other drugs that are undergoing clinical studies in UDCA non-responders include fibrates, such as fenofibrate and bezafibrate, which are pan–peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor (PPAR) agonists with anti-inflammatory and choleretic (enhanced bile secretion) effects.[51] Bezafibrate has been shown to improve biomarkers including alkaline phosphatase, but has not been licensed in PBC.[52][53]

Prognosis

The serum bilirubin level is an indicator of the prognosis of PBC, with levels of 2–6 mg/dL having a mean survival time of 4.1 years, 6–10 mg/dL having 2.1 years and those above 10 mg/dL having a mean survival time of 1.4 years.[54]

After liver transplant, the recurrence rate may be as high as 18 percent at five years, and up to 30 percent at 10 years. There is no consensus on risk factors for recurrence of the disease.[55]

Complications of PBC can be related to chronic cholestasis or cirrhosis of the liver. Chronic cholestasis leads to osteopenic bone disease and osteoporosis, alongside hyperlipidaemia and vitamin deficiencies.

Patients with PBC have an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma compared to the general population, as is found in other cirrhotic patients. In patients with advanced disease, one series found an incidence of 20 percent in men and 4 percent in women.[56]

Epidemiology

PBC is a chronic autoimmune liver disease with a female gender predominance with female:male ratio is at least 9:1 and a peak incidence in the fifth decade of life.[1][57] In some areas of the US and UK, the prevalence is estimated to be as high as 1 in 4000. This is much more common than in South America or Africa, which may be due to better recognition in the US and UK.[5][6] First-degree relatives may have as much as a 500 times increase in prevalence, but there is debate if this risk is greater in the same generation relatives or the one that follows.

History

In 1851, Addison and Gull described the clinical picture of progressive obstructive jaundice in the absence of mechanical obstruction of the large bile ducts.[58] Although most sources credit Ahrens with coining the term in 1950, Dauphinee and Sinclair had used the name primary biliary cirrhosis for this disease in 1949.[7] The association with anti-mitochondrial antibodies was first reported in 1965[59] and their presence was recognized as a marker of early, pre-cirrhotic disease.[60]

Society and culture

Support groups

PBC Foundation

The PBC Foundation is a UK-based international charity offering support and information to people with PBC, their families and friends.[61] It campaigns for increasing recognition of the disorder, improved diagnosis and treatments, and estimates over 8000 people are undiagnosed in the UK.[62][63] The Foundation has supported research into PBC including the development of the PBC-40 quality of life measure published in 2004[64] and helped establish the PBC Genetics Study.[20][65] It was founded by Collette Thain in 1996, after she was diagnosed with the condition.[62] Thain was awarded an MBE Order of the British Empire in 2004 for her work with the Foundation.[66] The PBC Foundation helped initiate the name change campaign in 2014.[8][9][67]

PBCers Organization

The PBCers Organization is a US-based non-profit patient support group that was founded by Linie Moore in 1996 and advocates for greater awareness of the disease and new treatments.[68] It has supported the initiative for a change in name.[9]

Name

In 2014 the PBC Foundation, with the support of the PBCers Organization, the PBC Society (Canada)[69] and other patient groups, advocated a change in name from "primary biliary cirrhosis" to "primary biliary cholangitis," noting that most PBC patients did not have cirrhosis and that "cirrhosis" often had negative connotations of alcoholism.[8][9][67] Patient and professional groups were canvassed.[70] Support for the name change came from professional bodies including the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases[71] and the European Association for the Study of the Liver.[72] Advocates for the name change published calls to adopt the new name in multiple hepatology journals in the fall of 2015.[70][72][73][74]

References

- Poupon R (2010). "Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: A 2010 Update". Journal of Hepatology. 52 (5): 745–758. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2009.11.027. PMID 20347176.

- Hirschfield GM, Gershwin ME (January 2013). "The Immunobiology and Pathophysiology of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". Annual Review of Pathology. 8: 303–330. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-164014. PMID 23347352.

- Dancygier, Henryk (2010). Principles and Practice of Clinical Hepatology. Springer. pp. 895–. ISBN 978-3-642-04509-7. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- Selmi C, Bowlus CL, Gershwin LE, Coppel RL (7 May 2011). "Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". Lancet. 377 (9777): 1600–1609. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61965-4. PMID 21529926.

- Boonstra K, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY (2012). "Epidemiology of Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis and Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: A Systematic Review". Journal of Hepatology. 56 (5): 1181–1188. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2011.10.025. PMID 22245904.

- James OF, Bhopal R, Howel D, et al. (1999). "Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Once Rare, Now Common in the United Kingdom?". Hepatology. 30 (2): 390–394. doi:10.1002/hep.510300213. PMID 10421645.

- Dauphinee, James A.; Sinclair, Jonathan C. (July 1949). "Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 61 (1): 1–6. PMC 1591584. PMID 18153470.

- PBC Foundation (UK). "PBC Name Change". Retrieved 27 Jan 2017.

- PBCers Organization. "Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Name Change Initiative" (PDF).

- Lindor KD, Gershwin ME, Poupon R, et al. (July 2009). "Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". Hepatology. 50 (1): 291–308. doi:10.1002/hep.22906. PMID 19554543.

The AASLD Practice Guideline

- Floreani A, Franceschet I, Cazzagon N (August 2014). "Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: Overlaps with Other Autoimmune Disorders". Seminars in Liver Disease. 34 (3): 352–360. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1383734. PMID 25057958.

- Webb GJ, Siminovitch KA, Hirschfield GM (2015). "The Immunogenetics of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: A Comprehensive Review". Journal of Autoimmunity. 64: 42–52. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2015.07.004. PMC 5014907. PMID 26250073.

- Saxena R, Theise N (February 2004). "Canals of Hering: Recent Insights and Current Knowledge". Seminars in Liver Disease. 24 (1): 43–48. doi:10.1055/s-2004-823100. PMID 15085485.

- Vierling JM (2004). "Primary Biliary Cirrhosis and Autoimmune Cholangiopathy". Clinical Liver Disease. 8 (1): 177–194. doi:10.1016/S1089-3261(03)00132-6. PMID 15062200.

- Watt FE, James OF, Jones DE (July 2004). "Patterns of Autoimmunity in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Patients and Their Families: a Population-Based Cohort Study". Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 97 (7): 397–406. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hch078. PMID 15208427.

- Narciso-Schiavon JL, Schiavon LL (2017). "To screen or not to screen? Celiac antibodies in liver diseases". World J Gastroenterol (Review). 23 (5): 776–791. doi:10.3748/wjg.v23.i5.776. PMC 5296194. PMID 28223722.

- Volta U, Rodrigo L, Granito A, et al. (October 2002). "Celiac Disease in Autoimmune Cholestatic Liver disorders". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 97 (10): 2609–2613. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.06031.x. PMID 12385447.

- Hirschfield GM, Liu X, Xu C, et al. (June 2009). "Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Associated with HLA, IL12A, and IL12RB2 Variants". The New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (24): 2544–2555. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810440. PMC 2857316. PMID 19458352.

- "UK-PBC – Stratified Medicine in Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC; formally known as Cirrhosis)".

- Liu JZ, Almarri MA, Gaffney DJ, et al. (October 2012). "Dense Fine-Mapping Study Identifies New Susceptibility Loci for Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". Nature Genetics. 44 (10): 1137–1141. doi:10.1038/ng.2395. PMC 3459817. PMID 22961000.

- Juran BD, Hirschfield GM, Invernizzi P, et al. (December 2012). "Immunochip Analyses Identify a Novel Risk Locus for Primary Biliary Cirrhosis at 13q14, Multiple Independent Associations at Four Established Risk Loci and Epistasis Between 1p31 and 7q32 Risk Variants". Human Molecular Genetics. 21 (23): 5209–5221. doi:10.1093/hmg/dds359. PMC 3490520. PMID 22936693.

- Hitomi Y, Ueno K, Kawai Y, Nishida N, Kojima K, Kawashima M, Aiba Y, Nakamura H, Kouno H, Kouno H, Ohta H, Sugi K, Nikami T, Yamashita T, Katsushima S, Komeda T, Ario K, Naganuma A, Shimada M, Hirashima N, Yoshizawa K, Makita F, Furuta K, Kikuchi M, Naeshiro N, Takahashi H, Mano Y, Yamashita H, Matsushita K, Tsunematsu S, Yabuuchi I, Nishimura H, Shimada Y, Yamauchi K, Komatsu T, Sugimoto R, Sakai H7, Mita E, Koda M, Nakamura Y, Kamitsukasa H, Sato T, Nakamuta M, Masaki N, Takikawa H, Tanaka A, Ohira H9, Zeniya M10, Abe M, Kaneko S, Honda M, Arai K, Arinaga-Hino T, Hashimoto E, Taniai M, Umemura T, Joshita S, Nakao K, Ichikawa T, Shibata H, Takaki A, Yamagiwa S, Seike M, Sakisaka S, Takeyama Y, Harada M, Senju M, Yokosuka O, Kanda T, Ueno Y, Ebinuma H, Himoto T, Murata K, Shimoda S, Nagaoka S, Abiru S, Komori A, Migita K, Ito M, Yatsuhashi H, Maehara Y, Uemoto S, Kokudo N, Nagasaki M, Tokunaga K, Nakamura M (2019) POGLUT1, the putative effector gene driven by rs2293370 in primary biliary cholangitis susceptibility locus chromosome 3q13.33. Sci Rep 9(1):102

- Selmi C, Balkwill DL, Invernizzi P, et al. (November 2003). "Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis React Against a Ubiquitous Xenobiotic-Metabolizing Bacterium". Hepatology. 38 (5): 1250–1257. doi:10.1053/jhep.2003.50446. PMID 14578864.

- Mohammed JP, Mattner J (July 2009). "Autoimmune Disease Triggered by Infection with Alphaproteobacteria". Expert Review of Clinical Immunology. 5 (4): 369–379. doi:10.1586/ECI.09.23. PMC 2742979. PMID 20161124.

- Kaplan MM (November 2004). "Novosphingobium aromaticivorans: a Potential Initiator of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 99 (11): 2147–2149. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.41121.x. PMID 15554995.

- Selmi C, Gershwin ME (July 2004). "Bacteria and Human Autoimmunity: The Case of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 16 (4): 406–410. doi:10.1097/01.bor.0000130538.76808.c2. PMID 15201604.

- Mattner J, Savage PB, Leung P, et al. (May 2008). "Liver Autoimmunity Triggered by Microbial Activation of Natural Killer T Cells". Cell Host & Microbe. 3 (5): 304–315. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2008.03.009. PMC 2453520. PMID 18474357.

- Mohammed JP, Fusakio ME, Rainbow DB, et al. (July 2011). "Identification of Cd101 as a Susceptibility Gene for Novosphingobium aromaticivorans-induced Liver Autoimmunity". Journal of Immunology. 187 (1): 337–349. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1003525. PMC 3134939. PMID 21613619.

- Nakamura M, Takii Y, Ito M, et al. (March 2006). "Increased expression of Nuclear Envelope gp210 Antigen in Small Bile Ducts in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". Journal of Autoimmunity. 26 (2): 138–145. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2005.10.007. PMID 16337775.

- Nickowitz RE, Worman HJ (1993). "Autoantibodies From Patients With Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Recognize a Restricted Region Within the Cytoplasmic Tail of Nuclear Pore Membrane Glycoprotein Gp210". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 178 (6): 2237–2242. doi:10.1084/jem.178.6.2237. PMC 2191303. PMID 7504063.

- Bauer A, Habior A (2007). "Measurement of gp210 Autoantibodies in sera of Patients With Primary Biliary cirrhosis". Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis. 21 (4): 227–231. doi:10.1002/jcla.20170. PMC 6648998. PMID 17621358.

- Nakamura M, Kondo H, Mori T, et al. (January 2007). "Anti-gp210 and Anti-Centromere Antibodies Are Different Risk Factors for the Progression of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". Hepatology. 45 (1): 118–127. doi:10.1002/hep.21472. PMID 17187436.

- Nesher G, Margalit R, Ashkenazi YJ (April 2001). "Anti-Nuclear Envelope Antibodies: Clinical Associations". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 30 (5): 313–320. doi:10.1053/sarh.2001.20266. PMID 11303304.

- Nakanuma Y, Tsuneyama K, Sasaki M, et al. (August 2000). "Destruction of Bile Ducts in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". Baillière's Best Practice & Research. Clinical Gastroenterology. 14 (4): 549–570. doi:10.1053/bega.2000.0103. PMID 10976014.

- Levy C, Lindor KD (April 2003). "Treatment Options for Primary Biliary Cirrhosis and Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis". Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology. 6 (2): 93–103. doi:10.1007/s11938-003-0010-0. PMID 12628068.

- Oo YH, Neuberger J (2004). "Options for treatment of primary biliary cirrhosis". Drugs. 64 (20): 2261–2271. doi:10.2165/00003495-200464200-00001. PMID 15456326.

- Rudic, Jelena S.; Poropat, Goran; Krstic, Miodrag N.; Bjelakovic, Goran; Gluud, Christian (2012-12-12). "Ursodeoxycholic acid for primary biliary cirrhosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12: CD000551. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000551.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 23235576.

- Walt RP, Daneshmend TK, Fellows IW, Toghill PJ (February 1988). "Effect of Stanozolol on Itching in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". British Medical Journal. 296 (6622): 607. doi:10.1136/bmj.296.6622.607. PMC 2545238. PMID 3126923.

- Abbas G, Jorgensen RA, Lindor KD (June 2010). "Fatigue in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 7 (6): 313–319. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2010.62. PMID 20458334.

- Modafinil#Primary biliary cirrhosis

Ian Gan S, de Jongh M, Kaplan MM (October 2009). "Modafinil in the Treatment of Debilitating Fatigue in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: A Clinical Experience". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 54 (10): 2242–2246. doi:10.1007/s10620-008-0613-3. PMID 19082890.

Kumagi T, Heathcote EJ (2008). "Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 3: 1. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-3-1. PMC 2266722. PMID 18215315.Ref 157 viz:

Jones DE, Newton JL (February 2007). "An Open Study of Modafinil for the Treatment of Daytime Somnolence and Fatigue in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 25 (4): 471–476. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03223.x. PMID 17270003. - Modafinil#Patent protection and antitrust litigation

Carrier MA (2011). "Provigil: A Case Study of Anticompetitive Behavior" (PDF). Hastings Science & Technology Law Journal. 3 (2): 441–452. - "Cephalon, Inc" (PDF). Federal Trade Commission. 2008-02-13.

- Bacon BR, O'Grady JG (2006). Comprehensive Clinical Hepatology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 283–. ISBN 978-0-323-03675-7. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- Collier JD, Ninkovic M, Compston JE (February 2002). "Guidelines on the Management of Osteoporosis Associated with Chronic Liver Disease". Gut. 50 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1): i1–9. doi:10.1136/gut.50.suppl_1.i1. PMC 1867644. PMID 11788576.

- Ali AH, Sinakos E, Silveira MG, et al. (August 2011). "Varices in Early Histological Stage Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 45 (7): e66–71. doi:10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181f18c4e. PMID 20856137.

- Clavien P, Killenberg PG (2006). Medical Care of the Liver Transplant Patient: Total Pre-, Intra- and Post-Operative Management. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-4051-3032-5.

- Kaneko J, Sugawara Y, Tamura S, et al. (January 2012). "Long-Term Outcome of Living Donor Liver Transplantation for Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". Transplant International. 25 (1): 7–12. doi:10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01336.x. PMID 21923804.

- Ali AH, Carey EJ, Lindor KD (January 2015). "Recent Advances in the Development of Farnesoid X Receptor Agonists". Annals of Translational Medicine. 3 (1): 5. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.12.06. PMC 4293481. PMID 25705637.

- "Package Insert for Ocaliva" (PDF). fda.gov. Intercept Pharmaceuticals. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- Egan, Amy G.(Deputy Director, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research). "Letter from Food and Drug Administration to Intercept Pharmaceuticals" (PDF). fda.gov. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- Suraweera, D; Rahal, H; Jimenez, M; Viramontes, M; Choi, G; Saab, S (December 2017). "Treatment of primary biliary cholangitis ursodeoxycholic acid non-responders: A systematic review". Liver International. 37 (12): 1877–1886. doi:10.1111/liv.13477. PMID 28517369.

- Levy, C; Lindor, KD (January 2018). "Editorial: Itching to Know: Role of Fibrates in PBC". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 113 (1): 56–57. doi:10.1038/ajg.2017.432. PMID 29311728.

- Carey, Elizabeth J. (7 June 2018). "Progress in Primary Biliary Cholangitis". New England Journal of Medicine. 378 (23): 2234–2235. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1804945. PMID 29874531.

- Primary Biliary Cirrhosis~followup at eMedicine

- Clavien & Killenberg 2006, p. 429

- Jones DE, Metcalf JV, Collier JD, et al. (November 1997). "Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis and Its Impact on Outcomes". Hepatology. 26 (5): 1138–1142. doi:10.1002/hep.510260508. PMID 9362353.

- Weinmann A, Sattler T, Unold HP, et al. (2014). "Predictive Scores in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: A Retrospective Single Center Analysis of 204 Patients". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 49 (5): 438–447. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000176. PMID 25014239.

- Reuben A (2003). "The serology of the Addison-Gull syndrome". Hepatology. 37 (1): 225–8. doi:10.1002/hep.510370134. PMID 12500211.

- Walker JG, Doniach D, Roitt IM, Sherlock S (April 1965). "Serological Tests in Diagnosis of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". Lancet. 1 (7390): 827–31. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(65)91372-3. PMID 14263538.

- Mitchison HC, Bassendine MF, Hendrick A, et al. (1986). "Positive Antimitochondrial Antibody but Normal Alkaline Phosphatase: Is this Primary Biliary Cirrhosis?". Hepatology. 6 (6): 1279–1284. doi:10.1002/hep.1840060609. PMID 3793004.

- Association of Medical Research Charities. "The PBC Foundation". Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- Staff of The Scotsman, January 3, 2008. Dealing with a silent killer

- Thain, Collette (2015). "Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: Getting a Diagnosis" (online). At Home Magazine. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- Jacoby A, Rannard A, Buck D, et al. (November 2005). "Development, Validation, and Evaluation of the PBC-40, a Disease Specific Health-Related Quality of Life Measure for Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". Gut. 54 (11): 1622–1629. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.065862. PMC 1774759. PMID 15961522.

- Mells GF, Floyd JA, Morley KI, et al. (April 2011). "Genome-Wide Association study Identifies 12 New Susceptibility Loci for Primary Biliary Cirrhosis". Nature Genetics. 43 (4): 329–332. doi:10.1038/ng.789. PMC 3071550. PMID 21399635.

- Barry Gordon for The Scotsman. 31 December 2003 A royal seal of approval

- PBC Foundation. "EASL Name Change Presentation". Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- Kim, Margot (2015-01-18). "New hope for PBC liver disease". ABC30 Action news. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- Cheung AC, Montano-Loza A, Swain M, et al. (2015). "Time to Make the Change from 'Primary Biliary Cirrhosis' to 'Primary Biliary Cholangitis'". Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 29 (6): 293. doi:10.1155/2015/764684. PMC 4578449. PMID 26196152.

- Beuers U, Gershwin ME, Gish RG, et al. (2015). "Changing Nomenclature for PBC: From 'Cirrhosis' to 'Cholangitis'". Gut. 64 (11): 1671–1672. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310593. PMID 26374822.

- AASLD. "A Name Change for PBC: Cholangitis Replacing Cirrhosis". Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Beuers U, Gershwin ME, Gish RG, et al. (2015). "Changing Nomenclature for PBC: From 'Cirrhosis' to 'Cholangitis'". Journal of Hepatology. 63 (5): 1285–1287. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2015.06.031. PMID 26385765.

- Beuers U, Gershwin ME, Gish RG, et al. (2015). "Changing Nomenclature for PBC: From 'Cirrhosis' to 'Cholangitis'". Hepatology. 62 (5): 1620–1622. doi:10.1002/hep.28140. PMID 26372460.

- Beuers U, Gershwin ME, Gish RG, et al. (2015). "Changing Nomenclature for PBC: From 'Cirrhosis' to 'Cholangitis'". Gastroenterology. 149 (6): 1627–1629. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.031. PMID 26385706.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Primary Biliary Cirrhosis page from the National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse

- Alagille syndrome