Prevalence of rabies

Almost all human deaths caused by rabies occur in Asia and Africa. There are an estimated 55,000 human deaths annually from rabies worldwide.[1]

Dog licensing, euthanasia of stray dogs, muzzling, and other measures contributed to the elimination of rabies from the United Kingdom in the early 20th century. More recently, large-scale vaccination of cats, dogs and ferrets has been successful in combating rabies in many developed countries.

Rabies is a zoonotic disease, caused by the rabies virus. The rabies virus, a member of the Lyssavirus genus of the Rhabdoviridae family, survives in a diverse variety of animal species, including bats, monkeys, raccoons, foxes, skunks, wolves, coyotes, dogs, mongoose, weasels, cats, cattle, domestic farm animals, groundhogs, bears, and wild carnivores. However, dogs are the principal host in Asia, parts of America, and large parts of Africa. Mandatory vaccination of animals is less effective in rural areas, especially in developing countries where pets may be community property and their destruction unacceptable. Oral vaccines can be safely administered to wild animals through bait, a method initiated on a large scale in Belgium that has successfully reduced rabies in rural areas of Canada, France, the United States, and elsewhere. For example, in Montreal baits are successfully ingested by raccoons in the Mount Royal park area.

Asia

An estimated 31,000 human deaths due to rabies occur annually in Asia,[1] with the majority – approximately 20,000 – concentrated in India.[2] Worldwide, India has the highest rate of human rabies in the world primarily due to stray dogs. Because of a decline in the number of vultures due to acute poisoning by the anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac (vultures themselves are not susceptible to rabies), animal carcasses that would have been consumed by vultures instead became available for consumption by feral dogs, resulting in a growth of the dog population and thus a larger pool of carriers for the rabies virus.[3] Another reason for the great increase in the number of stray dogs is the 2001 law that forbade the killing of dogs.[2]

In many Asian countries which still have a high prevalence of rabies, such as Vietnam and Thailand, the virus is primarily transmitted through canines (feral dogs and other wild canine species).[4] Another source of rabies in Asia is the pet boom.

Mainland China

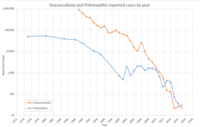

Historically, rabies was highly endemic in China, with few/inconsistent attempts to control transmission due to the lack of healthcare infrastructure. More than 5,200 deaths were reported annually during the period 1987 - 1989.[5] Infection is seasonal, with more cases reported during the spring and winter, with dogs being the most common animal vector.[6] The highest number of recorded cases was recorded in 1981, with 7037 human infections.[7] It was only until the 1990s did death rates decrease, as eradication efforts started being implemented on a nationwide level. The incidence of rabies decreased to fewer than 2000 cases per annum by 2011.[5] Despite this progress, rabies is still the third most common cause of death amongst category A and B infectious diseases, following HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis.

Chinese law requires all diagnosed rabies cases to be recorded in the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS) within 24 hours of diagnosis. Additionally, a questionnaire is used to interview patients and family members, in order to collect demographic information, as well as the means of exposure.[6]

Due to China's open organ transplant policy, an additional vector for the transmission of rabies is via donated organs. There has been 1 reported case of rabies transmission through organ donation in 2015, where a previously healthy 2-year-old patient was checked in to a hospital with unspecified symptoms. Rabies virus antibody tests were performed on serum samples and yielded negative results, which allowed the body to be used for donations despite suspicions from the clinical staff. The donor's kidneys and liver were transplanted to two other patients, who eventually died due to the rabies virus.[8]

In 2006 China introduced the "one-dog policy" in Beijing to control the problem.[9]

Indonesia

The island of Bali in Indonesia has been undergoing a severe outbreak of canine rabies since 2008, that has also killed about 78 humans as of late September 2010.[10] Unlike predominantly Muslim parts of Indonesia, in Bali many dogs are kept as pets and strays are tolerated in residential areas.[11] Efforts are under way to vaccinate pets and strays, as well as selective culling of some strays,[10] to control the outbreak. As Bali is a popular tourist destination, visitors are advised to consider rabies vaccinations before going there, if they will be touching animals.[12]

Israel

Since 1948, 29 people have been reported dead from rabies in Israel. The last death was in 2003, when a 58-year-old Bedouin woman was bitten by a cat and became infected. She was not inoculated and later died.[13]

Rabies is not endemic to Israel, but is imported from neighbouring countries. The areas of highest prevalence are along the northern region, which are close to Lebanon and Syria. Since the early 2000s, The Ministry of Agriculture and Israel Nature and National Parks Protection Authority (ILA) have dropped oral vaccines from planes in open and agricultural areas. The vaccine comes in the form of 3 by 3 cm. dumplings, made with an ingredient preferred by wild animals, and which contain a transgenic rabies virus. Cases of animal rabies dropped from 58 in 2009 to 29 in 2016.[14]

Japan

Rabies existed in Japan with a particular spike in the mid-1920s, but a dog vaccination campaign and increased stray dog control reduced cases.[15] The Rabies Control Act was enacted in 1950, and[16] the last human and animal cases were reported in 1954 and 1957,[17] and Japan is believed to have been rabies-free since 1957.[18]

There have been three imported cases since then, a college student who died in 1970, and two elderly men who had travelled to the Philippines and been bitten there by rabid dogs, and then died after returning to Japan.[15][19][20]

Africa

Approximately 24,000 people die from rabies annually in Africa,[21] which accounts for almost half the total rabies deaths worldwide each year.

South Africa

In South Africa, about a dozen cases of human rabies are confirmed every year[22] and it is particularly widespread in the north-eastern regions of the Eastern Cape, the eastern and south-eastern areas of Mpumalanga, northern Limpopo and KwaZulu-Natal.[23] Dogs are the main vector (especially in the east of the country) for the disease but also wildlife, including the bat-eared fox, yellow mongoose and black-backed jackal.[24] The death rate of 13 per annum over the decade 2001–2010 [25] is a rate of approximately 0.26 per million population. This is approximately 30 times the rate in the United States but 1/90th of the African average. The number of cases per province over the last decade are as follows:[26]

| Year | Eastern Cape | Free State | Gauteng | KwaZulu-Natal | Limpopo | Mpumalanga | Northern Cape | North-West | Western Cape | South Africa |

| 2001 | 6 | 1 | 7 | |||||||

| 2002 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||||||

| 2003 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 11 | ||||||

| 2004 | 7 | 1 | 8 | |||||||

| 2005 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | ||||||

| 2006 | 4 | 4 | 22 | 1 | 31 | |||||

| 2007 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 15 | ||||||

| 2008 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 17 | |||||

| 2009 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 15 | |||||

| 2010 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 | ||

| 2001 to 2010 | 31 | 1 | 1 | 57 | 31 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 133 |

| 2011 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | ||||||

| 2012 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 10 | ||||

| 2013 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 7 | |||||

| 2014 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||||||

| 2015 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 8 | |||||

| Average | 2.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 5.4 | 2.9 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 11.3 |

North America

United States

The United States as with other developed countries have seen a dramatic decrease in the number of human infections and deaths due to the rabies virus. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) the stark reduction in the number of rabies cases is attributable to the elimination of canine rabies through vaccination, the vaccination of wildlife, education about the virus, and timely administration of post exposure prophylaxis. Currently, in the U.S. only one to three cases of rabies are reported annually. Since 2008 there have been 23 cases of human rabies infection, eight of which were due to exposures outside of the U.S.[27] Human exposures to the virus is dependent on the prevalence of the virus in animals, thus investigations into the incidence and distribution of animal populations is vital. A breakdown of the results obtained from animal surveillance in the U.S. for 2015 revealed that wild animals accounted for 92.4% and domestic animals accounted for 7.6% of all reported cases.[28] In wild animals, bats were the most frequently reported rabid species (30.9% of cases during 2015), followed by raccoons (29.4%), skunks (24.8%), and foxes (5.9%).[29]

Southern United States

Rabies was once rare in the United States outside the Southern states, but raccoons in the mid-Atlantic and northeast United States have been suffering from a rabies epidemic since the 1970s, that is now moving westwards into Ohio.[30] Most westward expansion has been prevented via the action of Oral Rabies Vaccination (ORV) programs.[31]

The particular variant of the virus has been identified in the southeastern United States raccoon population since the 1950s, and is believed to have traveled to the northeast as the result of infected raccoons being among those caught and transported from the southeast to the northeast by human hunters attempting to replenish the declining northeast raccoon population.[32] As a result, urban residents of these areas have become more wary of the large but normally unseen urban raccoon population. Whether as a result of increased vigilance or only the common human avoidance reaction to any other animal not normally seen, such as a raccoon, there has only been one documented human rabies case as a result of this variant.[33][34] This does not include, however, the greatly increasing rate of prophylactic rabies treatments in cases of possible exposure, which numbered fewer than one hundred humans annually in the state of New York before 1990, for instance, but rose to approximately ten thousand annually between 1990 and 1995. At approximately $1,500 per course of treatment, this represents a considerable public health expenditure. Raccoons do constitute approximately 50% of the approximately eight thousand documented non-human rabies cases in the United States.[35] Domestic animals constitute only 8% of rabies cases, but are increasing at a rapid rate.[35]

Midwestern United States

In the midwestern United States, skunks are the primary carriers of rabies, composing 134 of the 237 documented non-human cases in 1996. The most widely distributed reservoir of rabies in the United States, however, and the source of most human cases in the U.S., are bats. Nineteen of the twenty-two human rabies cases documented in the United States between 1980 and 1997 have been identified genetically as bat rabies. In many cases, victims are not even aware of having been bitten by a bat, assuming that a small puncture wound found after the fact was the bite of an insect or spider; in some cases, no wound at all can be found, leading to the hypothesis that in some cases the virus can be contracted via inhaling airborne aerosols from the vicinity of bats. For instance, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warned on May 9, 1997, that a woman who died in October 1996 in Cumberland County, Kentucky and a man who died in December 1996 in Missoula County, Montana were both infected with a rabies strain found in silver-haired bats; although bats were found living in the chimney of the woman's home and near the man's workplace, neither victim could remember having had any contact with them.[36] Similar reports among spelunkers led to experimental demonstration in animals.[37] This inability to recognize a potential infection, in contrast to a bite from a dog or raccoon, leads to a lack of proper prophylactic treatment, and is the cause of the high mortality rate for bat bites.

On September 7, 2007, rabies expert Dr. Charles Rupprecht of Atlanta-based U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said that canine rabies had disappeared from the United States. Rupprecht emphasized that the disappearance of the canine-specific strain of rabies virus in the US does not eliminate the need for dog rabies vaccination as dogs can still become infected from exposure to wildlife.[38]

Southwestern United States

The primary terrestrial reservoirs for the Southwest states are skunks and foxes, with bats being identified as another important species for virus persistence in the environment. In Colorado the growing population pressures indicated by the increase in the number of residents by 9.2% between 2010 and 2016[39] has led to an elevated risk of rabies to the public. Additionally, according to Colorado Parks and Wildlife, reported cases, as well as the geographical distribution, in skunks, raccoons, and bats have increased; thereby further enhancing the likelihood of exposure. Together these increased risk factors have been documented in the state by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, which reported 141 positive animals; 95 of these reported animal cases were suspected to have exposed 180 domestic pets, 193 livestock animals, and 59 people.[40] In New Mexico the same trend of increased prevalence in wildlife has been observed with a reported 57% increase in the number of rabid bats.[41] As of 2017, there have been 11 confirmed cases of rabies in New Mexico: 5 bats, 2 skunks, 2 bobcats, and 2 foxes.[42] Conversely to these two states, Arizona in 2015 saw a drop in the number of confirmed rabies cases with a 21.3% decrease in reported skunk and fox rabies virus variants.[41] Furthermore, during that same time frame in Arizona 53.3% of all reported positive rabies cases were bats and 40% were identified as skunks.[43] Similarly, in 2015, Utah reported 22 positive cases of rabid bats.[44][41] For the year of 2016 Utah had identified 20 total positive cases of rabies, all of which pertained to only bat species.[45]

Europe

Several countries in Europe have been designated rabies-free jurisdictions: Austria, United Kingdom, Ireland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, France, Switzerland, Portugal, Italy, Spain, Greece, Malta, Germany, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Latvia, Estonia,[46] the Czech Republic, Iceland,[47] and the Republic of Cyprus.

Spain

The first case of rabies since 1978 was confirmed in the city of Toledo, Central Spain, on 5 June 2013. The dog had been imported from Morocco. No human fatalities have been reported, although adults and children were reported to have been bitten by the animal.[48]

Germany

Nine deaths from rabies were reported in Germany between 1981 and 2005. Two were caused by animal bites within Germany (one fox, one dog), and four were acquired abroad. In the remaining three cases, the source was a transplant from a donor who had died of rabies.[49] On 28 September 2008, the World Organisation for Animal Health declared Germany as free of rabies.[50]

Ireland

In 1897 the Disease of Animals Act included provisions to prevent the spread of rabies throughout Ireland. There have been no indigenous cases reported since 1903. In 2009, four people in Dublin received rabies vaccination therapy after being bitten by an imported kitten, although subsequent examination of the kitten yielded a negative result for rabies.[51][52]

United Kingdom

The UK was declared rabies free in 1902 but there were further outbreaks after 1918 when servicemen returning from war smuggled rabid dogs back to Britain. The disease was subsequently eradicated and Britain was declared rabies-free in 1922 after the introduction of compulsory quarantine for dogs.[49][53]

Since 1902, there have been 26 deaths in the UK from rabies (excluding the European bat lyssavirus 2 case discussed below).[49][54] A case in 1902 occurred shortly before the eradication of rabies from the UK, and no details were recorded for a case in 1919.[49] All other cases of rabies caused by rabies virus acquired the infection while abroad. Sixteen cases (62%) involved infections acquired in India, Pakistan or Bangladesh.[49]

Since 2000, four deaths from rabies have occurred; none of these cases had received any post-exposure prophylactic treatment. In 2001, there were two deaths from infections acquired in Nigeria and the Philippines. One death occurred in 2005 from an infection acquired by a dog bite in Goa (western India).[49][55] A woman died on 6 January 2009 in Belfast, Northern Ireland. She is believed to have been infected in South Africa, probably from being scratched by a dog.[56][57][58][59] Prior to this, the last reported human case of the disease in Northern Ireland was in 1938.[58][59] The most recent case was a woman who died on 28 May 2012 in London after being bitten by a dog in South Asia.[60]

A rabies-like lyssavirus, called European bat lyssavirus 2, was identified in bats in 2003.[55] In 2002, there was a fatal case in a bat handler involving infection with European bat lyssavirus 2; infection was probably acquired from a bite from a bat in Scotland.[49][55]

Benelux

The Netherlands has been designated rabies-free since 1923, Belgium since 2008. Isolated cases of rabies involving illegally smuggled pets from Africa, as well as infected animals crossing the German and French borders, do occur.[61]

Norway

The death of a woman on 6 May 2019 from the rabies virus was reported to be the first in Norway for almost 200 years. She contracted the virus while on holiday with friends in the Philippines, and after being bitten by a stray puppy they had rescued.[62]

Oceania

Australia

Australia is free of rabies. There have been two confirmed human deaths from the disease, in 1987 and 1990. Both were contracted overseas. However the closely related Australian Bat Lyssavirus (ABLV) has caused three deaths since its discovery in 1996, the most recent of these was in 2013 when an 8 year old Queensland boy was scratched on the wrist by an infected bat, developing rabies and dying 2 months afterwards.[63] There is also a report of an 1867 case.[64] There has been professional concern that the arrival of rabies in Australia is likely, given its wide spread presence in Australia's neighbour, Indonesia.[65]

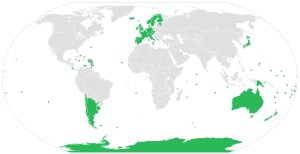

Rabies-free jurisdictions

Many countries and territories have been declared to be free of rabies. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published the following list based on countries and political units that reported no indigenous cases of rabies (excluding bat rabies) since 2009.

- Africa: Canary Islands, Cape Verde, Ceuta, Mayotte, Madeira Islands, Melilla, Réunion, Saint Helena

- Americas: Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Aruba, Ascension Island, Bahamas, Barbados, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Chile, Costa Rica, Dominica, Easter Island, Falkland Islands, Galapagos Islands, Guadeloupe, Jamaica, Martinique, Montserrat, Netherlands Antilles, Saint Kitts (Saint Christopher) and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Martin (Sint Maarten), Saint Vincent and Grenadines, South Georgia and South Sandwich Island, Trinidad and Tobago, Turks and Caicos Islands, Uruguay, Virgin Islands (British and U.S.)

- Asia and the Middle East: British Indian Ocean Territory, Cyprus, Hong Kong, Japan, Macau SAR, Maldives, Singapore

- Europe: Albania, Andorra, Austria, Azores, Balearic Islands, Belgium, Cabrera, Channel Islands, Corsica, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Faroe Islands, Finland, Formentera, France, Germany, Gibraltar, Ibiza, Iceland, Ireland, Isle of Man, Italy, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Majorca, Malta, Minorca, Monaco, Netherlands, Norway (except Svalbard), Portugal, San Marino, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom

- Oceania: American Samoa, Australia, Christmas Island, Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Cook Islands, Fiji, French Polynesia, Guam, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Nauru, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Niue, Norfolk Island, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Pitcairn Islands, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tahiti, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, Wake Islands and the US Pacific Islands, Wallis and Futuna Islands

- Antarctica: Antarctica

New Zealand and Australia have never had rabies. However, in Australia, the closely related Australian bat lyssavirus occurs normally in both insectivorous and fruit-eating bats (flying foxes) from most mainland states. Scientists believe it is present in bat populations throughout the range of flying foxes in Australia. Rabies has also never been reported in Cook Islands, Jersey in the Channel Islands, mainland Norway, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and Vanuatu.[69]

References

- "Rabies" World Health Organization (WHO)

- Harris, Gardiner (6 August 2012). "Where Streets Are Thronged With Strays Baring Fangs". New York Times. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- Dugan, Emily (30 April 2008). "Dead as a dodo? Why scientists fear for the future of the Asian vulture". United Kingdom: The Independent. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

India now has the highest rate of human rabies in the world, partly due to the increase in feral dogs.

- Denduangboripant J, Wacharapluesadee S, Lumlertdacha B, Ruankaew N, Hoonsuwan W, Puanghat A, Hemachudha T (June 2005). "Transmission dynamics of rabies virus in Thailand: implications for disease control". BMC Infectious Diseases. 5: 52. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-5-52. PMC 1184074. PMID 15985183.

- "Rabies". WHO Western Pacific Region. Retrieved 2018-01-15.

- Ren J, Gong Z, Chen E, Lin J, Lv H, Wang W, Liu S, Sun J (September 2015). "Human rabies in Zhejiang Province, China". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 38: 77–82. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2015.07.013. PMID 26216767.

- Zhou H, Vong S, Liu K, Li Y, Mu D, Wang L, Yin W, Yu H (August 2016). "Human Rabies in China, 1960-2014: A Descriptive Epidemiological Study". PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 10 (8): e0004874. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004874. PMC 4976867. PMID 27500957.

- Chen S, Zhang H, Luo M, Chen J, Yao D, Chen F, Liu R, Chen T (September 2017). "Rabies Virus Transmission in Solid Organ Transplantation, China, 2015-2016". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 23 (9): 1600–1602. doi:10.3201/eid2309.161704. PMC 5572883. PMID 28820377.

- "China cracks down on rabid dog menace". Toronto Star. 2007-07-23. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- Bali Turns Back to Vaccinations After Culling Fails to Curb Rabies Outbreak, Jakarta Globe, September 21, 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- Bali suffering rabies epidemic, The Sydney Morning Herald, August 6, 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- Rabies in Bali, Indonesia, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), March 29, 2010, Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- Rotem, Tsahar. "Negev woman bitten by cat, dies of rabies – Haaretz Daily Newspaper | Israel News". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- "מכת כלבת: עשרות נדבקים מדי שנה - כולם בצפון הארץ". וואלה! חדשות. 5 March 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- Yamada, Akio Challenges and risk for rabies free countries Retrieved July 15, 2016

- Inoue, Dr Satoshi http://www.npo-bmsa.org/ewf055.htm No.55 Prevention and risk management of rabies in Japan Retrieved July 15, 2016

- Takahashi-Omoe, Hiromi Regulatory Systems for Prevention and Control of Rabies, Japan Volume 14, Number 9—September 2008 Retrieved July 15, 2016

- Inoue, Dr Satoshi The Rabies Prevention and the Risk Management in Japan Retrieved July 15, 2016

- Rabies still poses a threat December 21, 2006 Japan Times Retrieved July 15, 2016

- Dog-bit Kyoto man who caught rabies in Philippines dies November 18, 2006 Japan Times Retrieved July 15, 2016

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-05-09. Retrieved 2011-12-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Ngubane, Nompendulo (2017-06-13). "Dogs stand in line for anti-rabies vaccinations". GroundUp. Retrieved 2017-06-13.

- "Rabies still kills in South Africa – but it doesn't have to". Bizcommunity.com. 2008-09-23. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- "Canadian Cooperation Centre – Research and testing: Rabies in South Africa". Psu-southafrica.org. Archived from the original on 2011-11-19. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- http://www.savc.org.za/pdf_docs/rabies_guide_2011.pdf

- "Rabies: Frequently Asked Questions", National Institute for Communicable Diseases, June 2016

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human Rabies. (2017, August 23). Retrieved October 25, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/location/usa/surveillance/human_rabies.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017, July 05). Rabies- Domestic Animals. Retrieved October 23, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/location/usa/surveillance/domestic_animals.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rabies- Wild Animals. (2017, July 05). Retrieved October 23, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/location/usa/surveillance/wild_animals.html

- "Compendium of animal rabies prevention and control, 2006: National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians, Inc. (NASPHV)" (PDF). MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 55 (RR-5): 1–8. April 2006. PMID 16636647.

- "Oral Rabies Vaccine Project – Environmental Epidemiology". www.vdh.virginia.gov. Retrieved 2017-07-23.

- Nettles VF, Shaddock JH, Sikes RK, Reyes CR (June 1979). "Rabies in translocated raccoons". American Journal of Public Health. 69 (6): 601–2. doi:10.2105/AJPH.69.6.601. PMC 1618975. PMID 443502.

- "First human death associated with raccoon rabies--Virginia, 2003" (PDF). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 52 (45): 1102–3. November 2003. PMID 14614408.

- "Rabies and Wildlife". The Humane Society of the United States. 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-06-15. Retrieved 2006-06-30.

- Krebs JW, Strine TW, Smith JS, Noah DL, Rupprecht CE, Childs JE (December 1996). "Rabies surveillance in the United States during 1995". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 209 (12): 2031–44. PMID 8960176.

- Human Rabies — Kentucky and Montana, 1996, May 9, 1997/Vol. 46/No. 18

- Constantine DG (April 1962). "Rabies transmission by nonbite route". Public Health Reports. 77: 287–9. doi:10.2307/4591470. PMC 1914752. PMID 13880956.

- Fox, Maggie (2007-09-07). "Reuters, U.S. free of canine rabies virus". Reuters.com. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- United States Census Bureau. (2016). Retrieved January 10, 2017, from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2016/demo/popest/state-total.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017, July 05) Rabies in Colorado. Retrieved January 10, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/location/usa/surveillance/domestic_animals.html

- Birhane, M. G., Cleaton, J. M., Monroe, B. P., Wadhwa, A., Orciari, L. A., Yager, P., ... & Wallace, R. M. (2017). Rabies surveillance in the United States during 2015. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 250(10), 1117–1130.

- New Mexico Department of Health. Rabies- Activity in New Mexico. (2017, October 17). Retrieved October 23, 2017, from https://nmhealth.org/about/erd/ideb/zdp/rab/

- Arizona Department of Health Services. 2015 Rabies Data. (2016, February 18). Retrieved October 28, 2017, from http://www.azdhs.gov/documents/preparedness/epidemiology-disease-control/rabies/data/2015.pdf

- Utah Department of Health. Utah Department of Health Monthly Rabies Report January–December 2015. (2016). Retrieved October 28, 2017, from http://health.utah.gov/epi/diseases/rabies/surveillance/

- Utah Department of Health. Utah Department of Health Monthly Rabies Report January–December 2016 (2017, September 5). Retrieved October 28, 2017, from http://health.utah.gov/epi/diseases/rabies/surveillance/

- "News - WSAVA Global Veterinary Community". www.wsava.org. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- http://www.who.int/rabies/Absence_Presence_Rabies_07_large.jpg

- office, PHE press. "Rabies in Spain: update 19 June 2013". GOV.UK. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- Johnson N, Brookes SM, Fooks AR, Ross RS. (2005) Review of human rabies cases in the UK and in Germany. Veterinary Record 157:715. doi:10.1136/vr.157.22.715. Retrieved 8 January 2009)

- "BMELV – Tiergesundheit – Deutschland ist frei von Tollwut" (in German). Bmelv.de. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- "The eradication of rabies / News / Issue 1 (Jan/Feb 2006) / Volume 14 / historyireland.com". Retrieved 2013-03-10.

- "Rabies: a new awareness in Ireland — Irish Medical Times". Retrieved 2013-03-10.

- "Wildlife Online – What is Rabies?". Retrieved 2013-03-10.

- 25 cases to 2005 (excluding the 2002 European bat lyssavirus 2 case), plus a case in Northern Ireland in January 2009

- Health Protection Agency: Rabies (Retrieved 8 January 2009)

- Health Protection Agency: Health Protection Report: News: Vol. 2, No. 51 (19 December 2008) (Retrieved 8 January 2009)

- "Woman with rabies dies in Belfast". RTÉ. 2009-01-07. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- "Woman treated for rabies in Belfast hospital". RTÉ. 2008-12-15. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- "Belfast woman dies of rabies". Irish Examiner. 7 January 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- "Woman with rabies dies at London hospital". BBC News. 2012-05-28.

- "Rabies(virus) (Infectieziektebestrijding)". Rivm.nl. 2011-01-03. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- "Woman dies of rabies after rescuing puppy". 10 May 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2019 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- Rabies – Queensland Government Retrieved July 15, 2016

- Attwood, Bronwyn Murdoch Rabies and Australian Bat Lyssavirus January 2007 Retrieved July 15, 2016

- Drewitt, Andy Health experts say Australia must brace for rabies arrival from Indonesia January 3, 2012 The Australian

- OIE Report on Re-Emergence of Rabies in Chinese Taipei

- "Taiwan informs OIE of 3 confirmed rabies cases - Society - FOCUS TAIWAN - CNA ENGLISH NEWS". focustaiwan.tw. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "Rabies outbreak in Perlis, Kedah and Penang". The Straits Times. 18 September 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "World Survey of Rabies No.34 1998" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-03-10.