Polycystic ovary syndrome

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a set of symptoms due to elevated androgens (male hormones) in females.[4][14] Signs and symptoms of PCOS include irregular or no menstrual periods, heavy periods, excess body and facial hair, acne, pelvic pain, difficulty getting pregnant, and patches of thick, darker, velvety skin.[3] Associated conditions include type 2 diabetes, obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, heart disease, mood disorders, and endometrial cancer.[4]

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hyperandrogenic anovulation (HA),[1] Stein–Leventhal syndrome[2] |

| |

| A polycystic ovary shown on an ultrasound image. | |

| Specialty | Gynecology |

| Symptoms | Irregular menstrual periods, heavy periods, excess hair, acne, pelvic pain, difficulty getting pregnant, patches of thick, darker, velvety skin[3] |

| Complications | Type 2 diabetes, obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, heart disease, mood disorders, endometrial cancer[4] |

| Duration | Long term[5] |

| Causes | Genetic and environmental factors[6][7] |

| Risk factors | Obesity, not enough exercise, family history[8] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on no ovulation, high androgen levels, ovarian cysts[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Adrenal hyperplasia, hypothyroidism, high blood levels of prolactin[9] |

| Treatment | Weight loss, exercise[10][11] |

| Medication | Birth control pills, metformin, anti-androgens[12] |

| Frequency | 2% to 20% of women of childbearing age[8][13] |

PCOS is due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors.[6][7][15] Risk factors include obesity, a lack of physical exercise, and a family history of someone with the condition.[8] Diagnosis is based on two of the following three findings: no ovulation, high androgen levels, and ovarian cysts.[4] Cysts may be detectable by ultrasound.[9] Other conditions that produce similar symptoms include adrenal hyperplasia, hypothyroidism, and high blood levels of prolactin.[9]

PCOS has no cure.[5] Treatment may involve lifestyle changes such as weight loss and exercise.[10][11] Birth control pills may help with improving the regularity of periods, excess hair growth, and acne.[12] Metformin and anti-androgens may also help.[12] Other typical acne treatments and hair removal techniques may be used.[12] Efforts to improve fertility include weight loss, clomiphene, or metformin.[16] In vitro fertilization is used by some in whom other measures are not effective.[16]

PCOS is the most common endocrine disorder among women between the ages of 18 and 44.[17] It affects approximately 2% to 20% of this age group depending on how it is defined.[8][13] When someone is infertile due to lack of ovulation, PCOS is the most common cause.[4] The earliest known description of what is now recognized as PCOS dates from 1721 in Italy.[18]

Signs and symptoms

Common signs and symptoms of PCOS include the following:

- Menstrual disorders: PCOS mostly produces oligomenorrhea (fewer than nine menstrual periods in a year) or amenorrhea (no menstrual periods for three or more consecutive months), but other types of menstrual disorders may also occur.[17]

- Infertility: This generally results directly from chronic anovulation (lack of ovulation).[17]

- High levels of masculinizing hormones: Known as hyperandrogenism, the most common signs are acne and hirsutism (male pattern of hair growth, such as on the chin or chest), but it may produce hypermenorrhea (heavy and prolonged menstrual periods), androgenic alopecia (increased hair thinning or diffuse hair loss), or other symptoms.[17][19] Approximately three-quarters of women with PCOS (by the diagnostic criteria of NIH/NICHD 1990) have evidence of hyperandrogenemia.[20]

- Metabolic syndrome: This appears as a tendency towards central obesity and other symptoms associated with insulin resistance.[17] Serum insulin, insulin resistance, and homocysteine levels are higher in women with PCOS.[21]

Women with PCOS tend to have central obesity, but studies are conflicting as to whether visceral and subcutaneous abdominal fat is increased, unchanged, or decreased in women with PCOS relative to reproductively normal women with the same body mass index.[22] In any case, androgens, such as testosterone, androstanolone (dihydrotestosterone), and nandrolone decanoate have been found to increase visceral fat deposition in both female animals and women.[23]

Cause

PCOS is a heterogeneous disorder of uncertain cause.[24][25] There is some evidence that it is a genetic disease. Such evidence includes the familial clustering of cases, greater concordance in monozygotic compared with dizygotic twins and heritability of endocrine and metabolic features of PCOS.[7][24][25] There is some evidence that exposure to higher than typical levels of androgens and the anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) in utero increases the risk of developing PCOS in later life.[26]

Genetics

The genetic component appears to be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion with high genetic penetrance but variable expressivity in females; this means that each child has a 50% chance of inheriting the predisposing genetic variant(s) from a parent, and, if a daughter receives the variant(s), the daughter will have the disease to some extent.[25][27][28][29] The genetic variant(s) can be inherited from either the father or the mother, and can be passed along to both sons (who may be asymptomatic carriers or may have symptoms such as early baldness and/or excessive hair) and daughters, who will show signs of PCOS.[27][29] The phenotype appears to manifest itself at least partially via heightened androgen levels secreted by ovarian follicle theca cells from women with the allele.[28] The exact gene affected has not yet been identified.[7][25][30] In rare instances, single-gene mutations can give rise to the phenotype of the syndrome.[31] Current understanding of the pathogenesis of the syndrome suggests, however, that it is a complex multigenic disorder.[32]

The severity of PCOS symptoms appears to be largely determined by factors such as obesity.[7][17][33]

PCOS has some aspects of a metabolic disorder, since its symptoms are partly reversible. Even though considered as a gynecological problem, PCOS consists of 28 clinical symptoms.

Even though the name suggests that the ovaries are central to disease pathology, cysts are a symptom instead of the cause of the disease. Some symptoms of PCOS will persist even if both ovaries are removed; the disease can appear even if cysts are absent. Since its first description by Stein and Leventhal in 1935, the criteria of diagnosis, symptoms, and causative factors are subject to debate. Gynecologists often see it as a gynecological problem, with the ovaries being the primary organ affected. However, recent insights show a multisystem disorder, with the primary problem lying in hormonal regulation in the hypothalamus, with the involvement of many organs. The name PCOD is used when there is ultrasonographic evidence. The term PCOS is used due to the fact that there is a wide spectrum of symptoms possible, and cysts in the ovaries are seen only in 15% of people.[34]

Environment

PCOS may be related to or worsened by exposures during the prenatal period, epigenetic factors, environmental impacts (especially industrial endocrine disruptors,[35] such as bisphenol A and certain drugs) and the increasing rates of obesity.[35][36][37][38][39][40][41]

Pathogenesis

Polycystic ovaries develop when the ovaries are stimulated to produce excessive amounts of androgenic hormones, in particular testosterone, by either one or a combination of the following (almost certainly combined with genetic susceptibility):[28]

- the release of excessive luteinizing hormone (LH) by the anterior pituitary gland[42]

- through high levels of insulin in the blood (hyperinsulinaemia) in women whose ovaries are sensitive to this stimulus

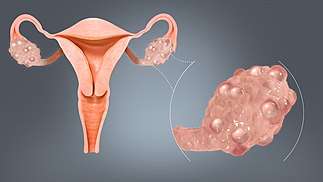

The syndrome acquired its most widely used name due to the common sign on ultrasound examination of multiple (poly) ovarian cysts. These "cysts" are actually immature follicles not cysts. The follicles have developed from primordial follicles, but the development has stopped ("arrested") at an early antral stage due to the disturbed ovarian function. The follicles may be oriented along the ovarian periphery, appearing as a 'string of pearls' on ultrasound examination.

Women with PCOS experience an increased frequency of hypothalamic GnRH pulses, which in turn results in an increase in the LH/FSH ratio.[43]

A majority of women with PCOS have insulin resistance and/or are obese. Their elevated insulin levels contribute to or cause the abnormalities seen in the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis that lead to PCOS. Hyperinsulinemia increases GnRH pulse frequency, LH over FSH dominance, increased ovarian androgen production, decreased follicular maturation, and decreased SHBG binding. Furthermore, excessive insulin, acting through its cognate receptor in the presence of component cAMP signalling, upregulates 17α-hydroxylase activity via PI3K, 17α-hydroxylase activity being responsible for synthesising androgen precursors. The combined effects of hyperinsulinemia contribute to an increased risk of PCOS.[44] Insulin resistance is a common finding among women with a normal weight as well as overweight women.[10][17][21]

Adipose tissue possesses aromatase, an enzyme that converts androstenedione to estrone and testosterone to estradiol. The excess of adipose tissue in obese women creates the paradox of having both excess androgens (which are responsible for hirsutism and virilization) and estrogens (which inhibits FSH via negative feedback).[45]

PCOS may be associated with chronic inflammation,[46] with several investigators correlating inflammatory mediators with anovulation and other PCOS symptoms.[47][48] Similarly, there seems to be a relation between PCOS and increased level of oxidative stress.[49]

It has previously been suggested that the excessive androgen production in PCOS could be caused by a decreased serum level of IGFBP-1, in turn increasing the level of free IGF-I, which stimulates ovarian androgen production, but recent data concludes this mechanism to be unlikely.[50]

PCOS has also been associated with a specific FMR1 sub-genotype. The research suggests that women with heterozygous-normal/low FMR1 have polycystic-like symptoms of excessive follicle-activity and hyperactive ovarian function.[51]

Transgender men on testosterone may experience a higher than expected rate of PCOS due to increased testosterone.[52][53]

Diagnosis

Not everyone with PCOS has polycystic ovaries (PCO), nor does everyone with ovarian cysts have PCOS; although a pelvic ultrasound is a major diagnostic tool, it is not the only one.[54] The diagnosis is straightforward using the Rotterdam criteria, even when the syndrome is associated with a wide range of symptoms.

Transvaginal ultrasound scan of polycystic ovary

Transvaginal ultrasound scan of polycystic ovary Polycystic ovary as seen on sonography

Polycystic ovary as seen on sonography

Definition

Two definitions are commonly used:

NIH

- In 1990 a consensus workshop sponsored by the NIH/NICHD suggested that a person has PCOS if they have all of the following:[55]

- oligoovulation

- signs of androgen excess (clinical or biochemical)

- exclusion of other disorders that can result in menstrual irregularity and hyperandrogenism

Rotterdam

- In 2003 a consensus workshop sponsored by ESHRE/ASRM in Rotterdam indicated PCOS to be present if any 2 out of 3 criteria are met, in the absence of other entities that might cause these findings[17][56][57]

- oligoovulation and/or anovulation

- excess androgen activity

- polycystic ovaries (by gynecologic ultrasound)

The Rotterdam definition is wider, including many more women, the most notable ones being women without androgen excess. Critics say that findings obtained from the study of women with androgen excess cannot necessarily be extrapolated to women without androgen excess.[58][59]

- Androgen Excess PCOS Society

- In 2006, the Androgen Excess PCOS Society suggested a tightening of the diagnostic criteria to all of the following:[17]

- excess androgen activity

- oligoovulation/anovulation and/or polycystic ovaries

- exclusion of other entities that would cause excess androgen activity

Standard assessment

- History-taking, specifically for menstrual pattern, obesity, hirsutism and acne. A clinical prediction rule found that these four questions can diagnose PCOS with a sensitivity of 77.1% (95% confidence interval [CI] 62.7%–88.0%) and a specificity of 93.8% (95% CI 82.8%–98.7%).[60]

- Gynecologic ultrasonography, specifically looking for small ovarian follicles. These are believed to be the result of disturbed ovarian function with failed ovulation, reflected by the infrequent or absent menstruation that is typical of the condition. In a normal menstrual cycle, one egg is released from a dominant follicle – in essence, a cyst that bursts to release the egg. After ovulation, the follicle remnant is transformed into a progesterone-producing corpus luteum, which shrinks and disappears after approximately 12–14 days. In PCOS, there is a so-called "follicular arrest"; i.e., several follicles develop to a size of 5–7 mm, but not further. No single follicle reaches the preovulatory size (16 mm or more). According to the Rotterdam criteria, which are widely used for diagnosis,[10] 12 or more small follicles should be seen in an ovary on ultrasound examination.[55] More recent research suggests that there should be at least 25 follicles in an ovary to designate it as having polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM) in women aged 18–35 years.[61] The follicles may be oriented in the periphery, giving the appearance of a 'string of pearls'.[62] If a high resolution transvaginal ultrasonography machine is not available, an ovarian volume of at least 10 ml is regarded as an acceptable definition of having polycystic ovarian morphology instead of follicle count.[61]

- Laparoscopic examination may reveal a thickened, smooth, pearl-white outer surface of the ovary. (This would usually be an incidental finding if laparoscopy were performed for some other reason, as it would not be routine to examine the ovaries in this way to confirm a diagnosis of PCOS.)

- Serum (blood) levels of androgens (hormones associated with male development), including androstenedione and testosterone may be elevated.[17] Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate levels above 700–800 µg/dL are highly suggestive of adrenal dysfunction because DHEA-S is made exclusively by the adrenal glands.[63][64] The free testosterone level is thought to be the best measure,[64][65] with ~60% of PCOS patients demonstrating supranormal levels.[20] The Free androgen index (FAI) of the ratio of testosterone to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) is high[17][64] and is meant to be a predictor of free testosterone, but is a poor parameter for this and is no better than testosterone alone as a marker for PCOS,[66] possibly because FAI is correlated with the degree of obesity.[67]

Some other blood tests are suggestive but not diagnostic. The ratio of LH (Luteinizing hormone) to FSH (Follicle-stimulating hormone), when measured in international units, is elevated in women with PCOS. Common cut-offs to designate abnormally high LH/FSH ratios are 2:1[68] or 3:1[64] as tested on Day 3 of the menstrual cycle. The pattern is not very sensitive; a ratio of 2:1 or higher was present in less than 50% of women with PCOS in one study.[68] There are often low levels of sex hormone-binding globulin,[64] in particular among obese or overweight women.[69] Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) is increased in PCOS, and may become part of its diagnostic criteria.[70][71][72]

Associated conditions

- Fasting biochemical screen and lipid profile[64]

- 2-Hour oral glucose tolerance test (GTT) in women with risk factors (obesity, family history, history of gestational diabetes)[17] may indicate impaired glucose tolerance (insulin resistance) in 15–33% of women with PCOS.[64] Frank diabetes can be seen in 65–68% of women with this condition. Insulin resistance can be observed in both normal weight and overweight people, although it is more common in the latter (and in those matching the stricter NIH criteria for diagnosis); 50–80% of people with PCOS may have insulin resistance at some level.[17]

- Fasting insulin level or GTT with insulin levels (also called IGTT). Elevated insulin levels have been helpful to predict response to medication and may indicate women needing higher dosages of metformin or the use of a second medication to significantly lower insulin levels. Elevated blood sugar and insulin values do not predict who responds to an insulin-lowering medication, low-glycemic diet, and exercise. Many women with normal levels may benefit from combination therapy. A hypoglycemic response in which the two-hour insulin level is higher and the blood sugar lower than fasting is consistent with insulin resistance. A mathematical derivation known as the HOMAI, calculated from the fasting values in glucose and insulin concentrations, allows a direct and moderately accurate measure of insulin sensitivity (glucose-level x insulin-level/22.5).

- Glucose tolerance testing (GTT) instead of fasting glucose can increase diagnosis of impaired glucose tolerance and frank diabetes among people with PCOS according to a prospective controlled trial.[73] While fasting glucose levels may remain within normal limits, oral glucose tests revealed that up to 38% of asymptomatic women with PCOS (versus 8.5% in the general population) actually had impaired glucose tolerance, 7.5% of those with frank diabetes according to ADA guidelines.[73]

Differential diagnosis

Other causes of irregular or absent menstruation and hirsutism, such as hypothyroidism, congenital adrenal hyperplasia (21-hydroxylase deficiency), Cushing's syndrome, hyperprolactinemia, androgen secreting neoplasms, and other pituitary or adrenal disorders, should be investigated.[17][57][64]

Management

The primary treatments for PCOS include: lifestyle changes and medications.[74]

Goals of treatment may be considered under four categories:

- Lowering of insulin resistance levels

- Restoration of fertility

- Treatment of hirsutism or acne

- Restoration of regular menstruation, and prevention of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer

In each of these areas, there is considerable debate as to the optimal treatment. One of the major reasons for this is the lack of large-scale clinical trials comparing different treatments. Smaller trials tend to be less reliable and hence may produce conflicting results.

General interventions that help to reduce weight or insulin resistance can be beneficial for all these aims, because they address what is believed to be the underlying cause.

As PCOS appears to cause significant emotional distress, appropriate support may be useful.[75]

Diet

Where PCOS is associated with overweight or obesity, successful weight loss is the most effective method of restoring normal ovulation/menstruation. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists guidelines recommend a goal of achieving 5 to 15% weight loss or more, which improves insulin resistance and all hormonal disorders.[76] However, many women find it very difficult to achieve and sustain significant weight loss. A scientific review in 2013 found similar decreases in weight and body composition and improvements in pregnancy rate, menstrual regularity, ovulation, hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, lipids, and quality of life to occur with weight loss independent of diet composition.[77] Still, a low GI diet, in which a significant part of total carbohydrates are obtained from fruit, vegetables, and whole-grain sources, has resulted in greater menstrual regularity than a macronutrient-matched healthy diet.[77]

Vitamin D deficiency may play some role in the development of the metabolic syndrome, so treatment of any such deficiency is indicated.[78][79] However, a systematic review of 2015 found no evidence that vitamin D supplementation reduced or mitigated metabolic and hormonal dysregulations in PCOS.[80] As of 2012, interventions using dietary supplements to correct metabolic deficiencies in people with PCOS had been tested in small, uncontrolled and nonrandomized clinical trials; the resulting data is insufficient to recommend their use.[81]

Medications

Medications for PCOS include oral contraceptives and metformin. The oral contraceptives increase sex hormone binding globulin production, which increases binding of free testosterone. This reduces the symptoms of hirsutism caused by high testosterone and regulates return to normal menstrual periods. Metformin is a medication commonly used in type 2 diabetes mellitus to reduce insulin resistance, and is used off label (in the UK, US, AU and EU) to treat insulin resistance seen in PCOS. In many cases, metformin also supports ovarian function and return to normal ovulation.[78][82] Spironolactone can be used for its antiandrogenic effects, and the topical cream eflornithine can be used to reduce facial hair. A newer insulin resistance medication class, the thiazolidinediones (glitazones), have shown equivalent efficacy to metformin, but metformin has a more favorable side effect profile.[83][84] The United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommended in 2004 that women with PCOS and a body mass index above 25 be given metformin when other therapy has failed to produce results.[85][86] Metformin may not be effective in every type of PCOS, and therefore there is some disagreement about whether it should be used as a general first line therapy.[87] In addition to this, metformin is associated with several unpleasant side effects: including abdominal pain, metallic taste in the mouth, diarrhoea and vomiting.[88] The use of statins in the management of underlying metabolic syndrome remains unclear.[89]

It can be difficult to become pregnant with PCOS because it causes irregular ovulation. Medications to induce fertility when trying to conceive include the ovulation inducer clomiphene or pulsatile leuprorelin. Metformin improves the efficacy of fertility treatment when used in combination with clomiphene.[90] Metformin is thought to be safe to use during pregnancy (pregnancy category B in the US).[91] A review in 2014 concluded that the use of metformin does not increase the risk of major birth defects in women treated with metformin during the first trimester.[92] Liraglutide may reduce weight and waist circumference more than other medications.[93]

Infertility

Not all women with PCOS have difficulty becoming pregnant. For those that do, anovulation or infrequent ovulation is a common cause. Other factors include changed levels of gonadotropins, hyperandrogenemia and hyperinsulinemia.[94] Like women without PCOS, women with PCOS that are ovulating may be infertile due to other causes, such as tubal blockages due to a history of sexually transmitted diseases.[95]

For overweight anovulatory women with PCOS, weight loss and diet adjustments, especially to reduce the intake of simple carbohydrates, are associated with resumption of natural ovulation.

For those women that after weight loss still are anovulatory or for anovulatory lean women, then the medications letrozole and clomiphene citrate are the principal treatments used to promote ovulation.[96][97][98] Previously, the anti-diabetes medication metformin was recommended treatment for anovulation, but it appears less effective than letrozole or clomiphene.[99][100]

For women not responsive to letrozole or clomiphene and diet and lifestyle modification, there are options available including assisted reproductive technology procedures such as controlled ovarian hyperstimulation with follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) injections followed by in vitro fertilisation (IVF).

Though surgery is not commonly performed, the polycystic ovaries can be treated with a laparoscopic procedure called "ovarian drilling" (puncture of 4–10 small follicles with electrocautery, laser, or biopsy needles), which often results in either resumption of spontaneous ovulations[78] or ovulations after adjuvant treatment with clomiphene or FSH. (Ovarian wedge resection is no longer used as much due to complications such as adhesions and the presence of frequently effective medications.) There are, however, concerns about the long-term effects of ovarian drilling on ovarian function.[78]

Hirsutism and acne

When appropriate (e.g., in women of child-bearing age who require contraception), a standard contraceptive pill is frequently effective in reducing hirsutism.[78] Progestogens such as norgestrel and levonorgestrel should be avoided due to their androgenic effects.[78]

Other medications with anti-androgen effects include flutamide,[101] and spironolactone,[78] which can give some improvement in hirsutism. Metformin can reduce hirsutism, perhaps by reducing insulin resistance, and is often used if there are other features such as insulin resistance, diabetes, or obesity that should also benefit from metformin. Eflornithine (Vaniqa) is a medication that is applied to the skin in cream form, and acts directly on the hair follicles to inhibit hair growth. It is usually applied to the face.[78] 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (such as finasteride and dutasteride) may also be used;[102] they work by blocking the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (the latter of which responsible for most hair growth alterations and androgenic acne).

Although these agents have shown significant efficacy in clinical trials (for oral contraceptives, in 60–100% of individuals[78]), the reduction in hair growth may not be enough to eliminate the social embarrassment of hirsutism, or the inconvenience of plucking or shaving. Individuals vary in their response to different therapies. It is usually worth trying other medications if one does not work, but medications do not work well for all individuals.

Menstrual irregularity

If fertility is not the primary aim, then menstruation can usually be regulated with a contraceptive pill.[78] The purpose of regulating menstruation, in essence, is for the woman's convenience, and perhaps her sense of well-being; there is no medical requirement for regular periods, as long as they occur sufficiently often.

If a regular menstrual cycle is not desired, then therapy for an irregular cycle is not necessarily required. Most experts say that, if a menstrual bleed occurs at least every three months, then the endometrium (womb lining) is being shed sufficiently often to prevent an increased risk of endometrial abnormalities or cancer.[103] If menstruation occurs less often or not at all, some form of progestogen replacement is recommended.[102] An alternative is oral progestogen taken at intervals (e.g., every three months) to induce a predictable menstrual bleeding.

Alternative medicine

A 2017 review concluded that while both myo-inositol and D-chiro-inositols may regulate menstrual cycles and improve ovulation, there is a lack of evidence regarding effects on the probability of pregnancy.[104][105] A 2012 and 2017 review have found myo-inositol supplementation appears to be effective in improving several of the hormonal disturbances of PCOS.[106][107] Myo-inositol reduces the amount of gonadotropins and the length of controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in women undergoing in vitro fertilization.[108] A 2011 review found not enough evidence to conclude any beneficial effect from D-chiro-inositol.[109] There is insufficient evidence to support the use of acupuncture.[110][111]

Prognosis

A diagnosis of PCOS suggests an increased risk of the following:

- Endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer (cancer of the uterine lining) are possible, due to overaccumulation of uterine lining, and also lack of progesterone resulting in prolonged stimulation of uterine cells by estrogen.[55][112] It is not clear whether this risk is directly due to the syndrome or from the associated obesity, hyperinsulinemia, and hyperandrogenism.[113][114][115]

- Insulin resistance/Type II diabetes. A review published in 2010 concluded that women with PCOS have an elevated prevalence of insulin resistance and type II diabetes, even when controlling for body mass index (BMI).[55][116] PCOS also makes a woman, particularly if obese, prone to gestational diabetes.

- High blood pressure, in particular if obese or during pregnancy

- Depression and anxiety[17][117]

- Dyslipidemia – disorders of lipid metabolism — cholesterol and triglycerides. Women with PCOS show a decreased removal of atherosclerosis-inducing remnants, seemingly independent of insulin resistance/Type II diabetes.

- Cardiovascular disease,[55] with a meta-analysis estimating a 2-fold risk of arterial disease for women with PCOS relative to women without PCOS, independent of BMI.[118]

- Strokes[55]

- Weight gain

- Miscarriage[119][120]

- Sleep apnea, particularly if obesity is present

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, again particularly if obesity is present

- Acanthosis nigricans (patches of darkened skin under the arms, in the groin area, on the back of the neck)[55]

- Autoimmune thyroiditis

The risk of ovarian cancer and breast cancer is not significantly increased overall.[112]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of PCOS depends on the choice of diagnostic criteria. The World Health Organization estimates that it affects 116 million women worldwide as of 2010 (3.4% of women).[121] Another estimate indicates that 7% of women of reproductive age are affected.[122] Well another study using the Rotterdam criteria found that about 18% of women had PCOS, and that 70% of them were previously undiagnosed.[17]

Ultrasonographic findings of polycystic ovaries are found in 8–25% of women non-affected by the syndrome.[123][124][125][126] 14% women on oral contraceptives are found to have polycystic ovaries.[124] Ovarian cysts are also a common side effect of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices (IUDs).[127]

History

The condition was first described in 1935 by American gynecologists Irving F. Stein, Sr. and Michael L. Leventhal, from whom its original name of Stein–Leventhal syndrome is taken.[54][55]

The earliest published description of a person with what is now recognized as PCOS was in 1721 in Italy.[18] Cyst-related changes to the ovaries were described in 1844.[18]

Society and culture

Funding

In 2005, 4 million cases of PCOS were reported in the US, costing $4.36 billion in healthcare costs.[128] In 2016 out of the National Institute Health's research budget of $32.3 billion for that year, 0.1% was spent on PCOS research.[129]

Names

Other names for this syndrome include polycystic ovarian syndrome, polycystic ovary disease, functional ovarian hyperandrogenism, ovarian hyperthecosis, sclerocystic ovary syndrome, and Stein–Leventhal syndrome. The eponymous last option is the original name; it is now used, if at all, only for the subset of women with all the symptoms of amenorrhea with infertility, hirsutism, and enlarged polycystic ovaries.[54]

Most common names for this disease derive from a typical finding on medical images, called a polycystic ovary. A polycystic ovary has an abnormally large number of developing eggs visible near its surface, looking like many small cysts.[54]

See also

- Androgen-dependent syndromes

- PCOS Challenge (reality television series)

References

- Kollmann M, Martins WP, Raine-Fenning N (2014). "Terms and thresholds for the ultrasound evaluation of the ovaries in women with hyperandrogenic anovulation". Hum. Reprod. Update. 20 (3): 463–4. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu005. PMID 24516084.

- "USMLE-Rx". MedIQ Learning, LLC. 2014.

Stein-Leventhal syndrome, also known as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), is a disorder characterized by hirsutism, obesity, and amenorrhea because of luteinizing hormone-resistant cystic ovaries.

Missing or empty|url=(help) - "What are the symptoms of PCOS?" (05/23/2013). National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Archived from the original on 3 March 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- "Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): Condition Information". National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. January 31, 2017. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- "Is there a cure for PCOS?". US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. 2013-05-23. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- De Leo V, Musacchio MC, Cappelli V, Massaro MG, Morgante G, Petraglia F (2016). "Genetic, hormonal and metabolic aspects of PCOS: an update". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology (Review). 14 (1): 38. doi:10.1186/s12958-016-0173-x. PMC 4947298. PMID 27423183.

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Kandarakis H (2006). "The role of genes and environment in the etiology of PCOS". Endocrine. 30 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1385/ENDO:30:1:19. PMID 17185788.

- "How many people are affected or at risk for PCOS?". http://www.nichd.nih.gov. 2013-05-23. Archived from the original on 4 March 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - "How do health care providers diagnose PCOS?". http://www.nichd.nih.gov/. 2013-05-23. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - Mortada R, Williams T (2015). "Metabolic Syndrome: Polycystic Ovary Syndrome". FP Essentials (Review). 435: 30–42. PMID 26280343.

- Giallauria F, Palomba S, Vigorito C, Tafuri MG, Colao A, Lombardi G, Orio F (2009). "Androgens in polycystic ovary syndrome: the role of exercise and diet". Seminars in Reproductive Medicine (Review). 27 (4): 306–15. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1225258. PMID 19530064.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) (2014-07-14). "Treatments to Relieve Symptoms of PCOS". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- editor, Lubna Pal (2013). "Diagnostic Criteria and Epidemiology of PCOS". Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Current and Emerging Concepts. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 7. ISBN 9781461483946. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- "Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) fact sheet". Women's Health. December 23, 2014. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- Dumesic DA, Oberfield SE, Stener-Victorin E, Marshall JC, Laven JS, Legro RS (2015). "Scientific Statement on the Diagnostic Criteria, Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Molecular Genetics of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome". Endocrine Reviews (Review). 36 (5): 487–525. doi:10.1210/er.2015-1018. PMC 4591526. PMID 26426951.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) (2014-07-14). "Treatments for Infertility Resulting from PCOS". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Teede H, Deeks A, Moran L (2010). "Polycystic ovary syndrome: a complex condition with psychological, reproductive and metabolic manifestations that impacts on health across the lifespan". BMC Med. 8 (1): 41. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-41. PMC 2909929. PMID 20591140.

- Kovacs, Gabor T.; Norman, Robert (2007-02-22). Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9781139462037. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- Christine Cortet-Rudelli; Didier Dewailly (Sep 21, 2006). "Diagnosis of Hyperandrogenism in Female Adolescents". Hyperandrogenism in Adolescent Girls. Armenian Health Network, Health.am. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- Huang A, Brennan K, Azziz R (2010). "Prevalence of hyperandrogenemia in the polycystic ovary syndrome diagnosed by the National Institutes of Health 1990 criteria". Fertil. Steril. 93 (6): 1938–41. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.138. PMC 2859983. PMID 19249030.

- Nafiye Y, Sevtap K, Muammer D, Emre O, Senol K, Leyla M (2010). "The effect of serum and intrafollicular insulin resistance parameters and homocysteine levels of nonobese, nonhyperandrogenemic polycystic ovary syndrome patients on in vitro fertilization outcome". Fertil. Steril. 93 (6): 1864–9. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.024. PMID 19171332.

- Sam S (February 2015). "Adiposity and metabolic dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome". Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 21 (2): 107–16. doi:10.1515/hmbci-2015-0008. PMID 25781555.

- Corbould A (October 2008). "Effects of androgens on insulin action in women: is androgen excess a component of female metabolic syndrome?". Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 24 (7): 520–32. doi:10.1002/dmrr.872. PMID 18615851.

- Page 836 (Section:Polycystic ovary syndrome) in: Fauser BC, Diedrich K, Bouchard P, Domínguez F, Matzuk M, Franks S, Hamamah S, Simón C, Devroey P, Ezcurra D, Howles CM (2011). "Contemporary genetic technologies and female reproduction". Hum. Reprod. Update. 17 (6): 829–47. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr033. PMC 3191938. PMID 21896560.

- Legro RS, Strauss JF (2002). "Molecular progress in infertility: polycystic ovary syndrome". Fertil. Steril. 78 (3): 569–76. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03275-2. PMID 12215335.

- Filippou, P; Homburg, R (1 July 2017). "Is foetal hyperexposure to androgens a cause of PCOS?". Human Reproduction Update. 23 (4): 421–432. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmx013. PMID 28531286.

- Crosignani PG, Nicolosi AE (2001). "Polycystic ovarian disease: heritability and heterogeneity". Hum. Reprod. Update. 7 (1): 3–7. doi:10.1093/humupd/7.1.3. PMID 11212071.

- Strauss JF (2003). "Some new thoughts on the pathophysiology and genetics of polycystic ovary syndrome". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 997 (1): 42–8. Bibcode:2003NYASA.997...42S. doi:10.1196/annals.1290.005. PMID 14644808.

- Ada Hamosh (12 September 2011). "POLYCYSTIC OVARY SYNDROME 1; PCOS1". OMIM. McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- Amato P, Simpson JL (2004). "The genetics of polycystic ovary syndrome". Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 18 (5): 707–18. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.05.002. PMID 15380142.

- Draper; et al. (2003). "Mutations in the genes encoding 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase interact to cause cortisone reductase deficiency". Nature Genetics. 34 (4): 434–439. doi:10.1038/ng1214. PMID 12858176.

- Ehrmann David A (2005). "Polycystic Ovary Syndrome". N Engl J Med. 352 (6039): 1223–1236. doi:10.1056/NEJMra041536. PMID 15788499.

- Faghfoori Z, Fazelian S, Shadnoush M, Goodarzi R (2017). "Nutritional management in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A review study". Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome (Review). 11 Suppl 1: S429–S432. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2017.03.030. PMID 28416368.

- Dunaif A, Fauser BC (2013). "Renaming PCOS—a two-state solution". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98 (11): 4325–8. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-2040. PMC 3816269. PMID 24009134.

- Palioura E, Diamanti-Kandarakis E (2013). "Industrial endocrine disruptors and polycystic ovary syndrome". J. Endocrinol. Invest. 36 (11): 1105–11. doi:10.1007/bf03346762. PMID 24445124.

- Hoeger KM (2014). "Developmental origins and future fate in PCOS". Semin. Reprod. Med. 32 (3): 157–158. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1371086. PMID 24715509.

- Harden CL (2005). "Polycystic ovaries and polycystic ovary syndrome in epilepsy: evidence for neurogonadal disease". Epilepsy Curr. 5 (4): 142–6. doi:10.1111/j.1535-7511.2005.00039.x. PMC 1198730. PMID 16151523.

- Rasgon N (2004). "The relationship between polycystic ovary syndrome and antiepileptic drugs: a review of the evidence". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 24 (3): 322–34. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000125745.60149.c6. PMID 15118487.

- Hu X, Wang J, Dong W, Fang Q, Hu L, Liu C (2011). "A meta-analysis of polycystic ovary syndrome in women taking valproate for epilepsy". Epilepsy Res. 97 (1–2): 73–82. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.07.006. PMID 21820873.

- Abbott DH, Barnett DK, Bruns CM, Dumesic DA (2005). "Androgen excess fetal programming of female reproduction: a developmental aetiology for polycystic ovary syndrome?". Hum. Reprod. Update. 11 (4): 357–74. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmi013. PMID 15941725.

- Rutkowska A, Rachoń D (2014). "Bisphenol A (BPA) and its potential role in the pathogenesis of the polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 30 (4): 260–5. doi:10.3109/09513590.2013.871517. PMID 24397396.

- "What is Luteinizing Hormone?". Hormone.org. Endocrine Society. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- Lewandowski KC, Cajdler-Łuba A, Salata I, Bieńkiewicz M, Lewiński A (2011). "The utility of the gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) test in the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)". Endokrynol Pol. 62 (2): 120–8. PMID 21528473.

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, Evanthia; Dunaif, Andrea (December 2012). "Insulin Resistance and the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Revisited: An Update on Mechanisms and Implications". Endocrine Reviews. 33 (6): 981–1030. doi:10.1210/er.2011-1034. PMC 5393155. PMID 23065822.

- Kumar Cotran Robbins: Basic Pathology 6th ed. / Saunders 1996

- Sathyapalan T, Atkin SL (2010). "Mediators of inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome in relation to adiposity". Mediators Inflamm. 2010: 1–5. doi:10.1155/2010/758656. PMC 2852606. PMID 20396393.

- Fukuoka M, Yasuda K, Fujiwara H, Kanzaki H, Mori T (1992). "Interactions between interferon gamma, tumour necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-1 in modulating progesterone and oestradiol production by human luteinized granulosa cells in culture". Hum. Reprod. 7 (10): 1361–4. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137574. PMID 1291559.

- González F, Rote NS, Minium J, Kirwan JP (2006). "Reactive oxygen species-induced oxidative stress in the development of insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism in polycystic ovary syndrome". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 91 (1): 336–40. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-1696. PMID 16249279.

- Murri M, Luque-Ramírez M, Insenser M, Ojeda-Ojeda M, Escobar-Morreale HF (2013). "Circulating markers of oxidative stress and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a systematic review and meta-analysis". Hum. Reprod. Update. 19 (3): 268–88. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms059. PMID 23303572.

- Kelly CJ, Stenton SR, Lashen H (2010). "Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 in PCOS: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Hum. Reprod. Update. 17 (1): 4–16. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq027. PMID 20634211.

- Gleicher N, Weghofer A, Lee IH, Barad DH (2010). "FMR1 genotype with autoimmunity-associated polycystic ovary-like phenotype and decreased pregnancy chance". PLoS ONE. 5 (12): e15303. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...515303G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015303. PMC 3002956. PMID 21179569.

- "Transgender/PCOS". 2006-09-20. Archived from the original on 2014-10-25. Retrieved 2014-10-24.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-05-10. Retrieved 2015-05-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Marrinan, Greg (20 April 2011). Lin, Eugene C (ed.). "Imaging in Polycystic Ovary Disease". eMedicine. eMedicine. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- Richard Scott Lucidi (25 October 2011). "Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome". eMedicine. Archived from the original on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- Azziz R (2006). "Controversy in clinical endocrinology: diagnosis of polycystic ovarian syndrome: the Rotterdam criteria are premature". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 91 (3): 781–5. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-2153. PMID 16418211.

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group (2004). "Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)". Hum. Reprod. 19 (1): 41–7. doi:10.1093/humrep/deh098. PMID 14688154.

- Carmina E (2004). "Diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome: from NIH criteria to ESHRE-ASRM guidelines". Minerva Ginecol. 56 (1): 1–6. PMID 14973405.

- Hart R, Hickey M, Franks S (2004). "Definitions, prevalence and symptoms of polycystic ovaries and polycystic ovary syndrome". Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 18 (5): 671–83. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.05.001. PMID 15380140.

- Pedersen SD, Brar S, Faris P, Corenblum B (2007). "Polycystic ovary syndrome: validated questionnaire for use in diagnosis". Can Fam Physician. 53 (6): 1042–7, 1041. PMC 1949220. PMID 17872783.

- Dewailly D, Lujan ME, Carmina E, Cedars MI, Laven J, Norman RJ, Escobar-Morreale HF (2013). "Definition and significance of polycystic ovarian morphology: a task force report from the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society". Hum. Reprod. Update. 20 (3): 334–52. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt061. PMID 24345633.

- O'Brien, William T. (1 January 2011). Top 3 Differentials in Radiology. Thieme. p. 369. ISBN 978-1-60406-228-1. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

Ultrasound findings in PCOS include enlarged ovaries with peripheral follicles in a "string of pearls" configuration.

- Somani N, Harrison S, Bergfeld WF (2008). "The clinical evaluation of hirsutism". Dermatol Ther. 21 (5): 376–91. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00219.x. PMID 18844715.

- "Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome Workup". eMedicine. 25 October 2011. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- Sharquie KE, Al-Bayatti AA, Al-Ajeel AI, Al-Bahar AJ, Al-Nuaimy AA (2007). "Free testosterone, luteinizing hormone/follicle stimulating hormone ratio and pelvic sonography in relation to skin manifestations in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome". Saudi Med J. 28 (7): 1039–43. PMID 17603706.

- Robinson S, Rodin DA, Deacon A, Wheeler MJ, Clayton RN (1992). "Which hormone tests for the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome?". Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 99 (3): 232–8. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb14505.x. PMID 1296589.

- Li X, Lin JF (2005). "[Clinical features, hormonal profile, and metabolic abnormalities of obese women with obese polycystic ovary syndrome]". Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (in Chinese). 85 (46): 3266–71. PMID 16409817.

- Banaszewska B, Spaczyński RZ, Pelesz M, Pawelczyk L (2003). "Incidence of elevated LH/FSH ratio in polycystic ovary syndrome women with normo- and hyperinsulinemia". Rocz. Akad. Med. Bialymst. 48: 131–4. PMID 14737959.

- Macpherson, Gordon (2002). Black's Medical Dictionary (40 ed.). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. p. 496. ISBN 0810849844.

- Dumont A, Robin G, Catteau-Jonard S, Dewailly D (2015). "Role of Anti-Müllerian Hormone in pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: a review". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology (Review). 13: 137. doi:10.1186/s12958-015-0134-9. PMC 4687350. PMID 26691645.

- Dewailly D, Andersen CY, Balen A, Broekmans F, Dilaver N, Fanchin R, Griesinger G, Kelsey TW, La Marca A, Lambalk C, Mason H, Nelson SM, Visser JA, Wallace WH, Anderson RA (2014). "The physiology and clinical utility of anti-Mullerian hormone in women". Human Reproduction Update (Review). 20 (3): 370–85. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt062. PMID 24430863.

- Broer SL, Broekmans FJ, Laven JS, Fauser BC (2014). "Anti-Müllerian hormone: ovarian reserve testing and its potential clinical implications". Hum. Reprod. Update. 20 (5): 688–701. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu020. PMID 24821925.

- Legro RS, Kunselman AR, Dodson WC, Dunaif A (1999). "Prevalence and predictors of risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in polycystic ovary syndrome: a prospective, controlled study in 254 affected women". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 84 (1): 165–9. doi:10.1210/jcem.84.1.5393. PMID 9920077.

- Legro, Richard S.; Arslanian, Silva A.; Ehrmann, David A.; Hoeger, Kathleen M.; Murad, M. Hassan; Pasquali, Renato; Welt, Corrine K.; Endocrine Society (December 2013). "Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 98 (12): 4565–4592. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-2350. ISSN 1945-7197. PMC 5399492. PMID 24151290.

- Veltman-Verhulst SM, Boivin J, Eijkemans MJ, Fauser BJ (2012). "Emotional distress is a common risk in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 28 studies". Hum. Reprod. Update. 18 (6): 638–51. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms029. PMID 22824735.

- Garvey, WT; Mechanick, JI; Brett, EM; Garber, AJ; Hurley, DL; Jastreboff, AM; Nadolsky, K; Pessah-Pollack, R; Plodkowski, R; Reviewers of the AACE/ACE Obesity Clinical Practice, Guidelines. (July 2016). "American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Comprehensive Clinical Practice Guidelines for Medical Care of Patients with Obesity". Endocrine Practice. 22 Suppl 3: 1–203. doi:10.4158/EP161365.GL. PMID 27219496.

- Moran LJ, Ko H, Misso M, Marsh K, Noakes M, Talbot M, Frearson M, Thondan M, Stepto N, Teede HJ (2013). "Dietary composition in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review to inform evidence-based guidelines". Hum. Reprod. Update. 19 (5): 432. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt015. PMID 23727939.

- "Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome Treatment & Management". eMedicine. 25 October 2011. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- Krul-Poel YH, Snackey C, Louwers Y, Lips P, Lambalk CB, Laven JS, Simsek S (2013). "The role of vitamin D in metabolic disturbances in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review". European Journal of Endocrinology (Review). 169 (6): 853–65. doi:10.1530/EJE-13-0617. PMID 24044903.

- He C, Lin Z, Robb SW, Ezeamama AE (2015). "Serum Vitamin D Levels and Polycystic Ovary syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Nutrients (Meta-analysis). 7 (6): 4555–77. doi:10.3390/nu7064555. PMC 4488802. PMID 26061015.

- Huang, G; Coviello, A (December 2012). "Clinical update on screening, diagnosis and management of metabolic disorders and cardiovascular risk factors associated with polycystic ovary syndrome". Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 19 (6): 512–9. doi:10.1097/med.0b013e32835a000e. PMID 23108199.

- Lord JM, Flight IH, Norman RJ (2003). "Metformin in polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 327 (7421): 951–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7421.951. PMC 259161. PMID 14576245.

- Li, X.-J.; Yu, Y.-X.; Liu, C.-Q.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.-J.; Yan, B.; Wang, L.-Y.; Yang, S.-Y.; Zhang, S.-H. (March 2011). "Metformin vs thiazolidinediones for treatment of clinical, hormonal and metabolic characteristics of polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis". Clinical Endocrinology. 74 (3): 332–339. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03917.x. ISSN 1365-2265. PMID 21050251.

- Grover, Anjali; Yialamas, Maria A. (March 2011). "Metformin or thiazolidinedione therapy in PCOS?". Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 7 (3): 128–. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2011.16. ISSN 1759-5029. PMID 21283123. Archived from the original on 2015-07-22. Retrieved 2015-05-24.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 11 Clinical guideline 11 : Fertility: assessment and treatment for people with fertility problems . London, 2004.

- Balen A (December 2008). "Metformin therapy for the management of infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome" (PDF). Scientific Advisory Committee Opinion Paper 13. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-18. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- Leeman L, Acharya U (2009). "The use of metformin in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome and associated anovulatory infertility: the current evidence". J Obstet Gynaecol. 29 (6): 467–72. doi:10.1080/01443610902829414. PMID 19697191.

- NICE (December 2018). "Metformin Hydrochloride". National Institute for Care Excellence. NICE. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- Legro, RS; Arslanian, SA; Ehrmann, DA; Hoeger, KM; Murad, MH; Pasquali, R; Welt, CK; Endocrine, Society (December 2013). "Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 98 (12): 4565–92. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-2350. PMC 5399492. PMID 24151290.

- Nestler, John E.; Jakubowicz, Daniela J.; Evans, William S.; Pasquali, Renato (1998-06-25). "Effects of Metformin on Spontaneous and Clomiphene-Induced Ovulation in the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome". New England Journal of Medicine. 338 (26): 1876–1880. doi:10.1056/NEJM199806253382603. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 9637806.

- Feig, Denice S.; Moses, Robert G. (2011-10-01). "Metformin Therapy During Pregnancy Good for the goose and good for the gosling too?". Diabetes Care. 34 (10): 2329–2330. doi:10.2337/dc11-1153. ISSN 0149-5992. PMC 3177745. PMID 21949224. Archived from the original on 2015-05-25. Retrieved 2015-05-24.

- Cassina M, Donà M, Di Gianantonio E, Litta P, Clementi M (2014). "First-trimester exposure to metformin and risk of birth defects: a systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). Hum. Reprod. Update. 20 (5): 656–69. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu022. PMID 24861556.

- Wang, F.-F.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Y.-H.; Ding, T.; Batterham, R. L.; Qu, F.; Hardiman, P. J. (2018-07-31). "Pharmacologic therapy to induce weight loss in women who have obesity/overweight with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". Obesity Reviews. 19 (10): 1424–1445. doi:10.1111/obr.12720. ISSN 1467-789X. PMID 30066361.

- Qiao J, Feng HL (2010). "Extra- and intra-ovarian factors in polycystic ovary syndrome: impact on oocyte maturation and embryo developmental competence". Hum. Reprod. Update. 17 (1): 17–33. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq032. PMC 3001338. PMID 20639519.

- "What are some causes of female infertility?". National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

- Franik, Sebastian; Eltrop, Stephanie M.; Kremer, Jan Am; Kiesel, Ludwig; Farquhar, Cindy (May 24, 2018). "Aromatase inhibitors (letrozole) for subfertile women with polycystic ovary syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5: CD010287. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010287.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6494577. PMID 29797697.

- Tanbo, Tom; Mellembakken, Jan; Bjercke, Sverre; Ring, Eva; Åbyholm, Thomas; Fedorcsak, Peter (October 2018). "Ovulation induction in polycystic ovary syndrome". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 97 (10): 1162–1167. doi:10.1111/aogs.13395. ISSN 1600-0412. PMID 29889977.

- Hu, Shifu; Yu, Qiong; Wang, Yingying; Wang, Mei; Xia, Wei; Zhu, Changhong (May 2018). "Letrozole versus clomiphene citrate in polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 297 (5): 1081–1088. doi:10.1007/s00404-018-4688-6. ISSN 1432-0711. PMID 29392438.

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (September 2017). "Role of metformin for ovulation induction in infertile patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a guideline". Fertility and Sterility. 108 (3): 426–441. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.06.026. ISSN 1556-5653. PMID 28865539.

- Legro RS, Barnhart HX, Schlaff WD, Carr BR, Diamond MP, Carson SA, Steinkampf MP, Coutifaris C, McGovern PG, Cataldo NA, Gosman GG, Nestler JE, Giudice LC, Leppert PC, Myers ER (2007). "Clomiphene, metformin, or both for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome". N. Engl. J. Med. 356 (6): 551–66. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa063971. PMID 17287476.

- "Polycystic ovary syndrome – Treatment". United Kingdom: National Health Service. 17 October 2011. Archived from the original on 6 November 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- Richard Scott Lucidi (25 October 2011). "Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome Medication". eMedicine. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- "What are the health risks of PCOS?". Verity – PCOS Charity. Verity. 2011. Archived from the original on 25 December 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- Pundir, J; Psaroudakis, D; Savnur, P; Bhide, P; Sabatini, L; Teede, H; Coomarasamy, A; Thangaratinam, S (24 May 2017). "Inositol treatment of anovulation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomised trials" (PDF). BJOG : An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 125 (3): 299–308. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14754. PMID 28544572.

- Amoah-Arko, Afua; Evans, Meirion; Rees, Aled (2017-10-20). "Effects of myoinositol and D-chiro inositol on hyperandrogenism and ovulation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review". Endocrine Abstracts. doi:10.1530/endoabs.50.P363.

- Unfer V, Carlomagno G, Dante G, Facchinetti F (2012). "Effects of myo-inositol in women with PCOS: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 28 (7): 509–15. doi:10.3109/09513590.2011.650660. PMID 22296306.

- Zeng, Liuting; Yang, Kailin (2017-10-19). "Effectiveness of myoinositol for polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Endocrine. 59 (1): 30–38. doi:10.1007/s12020-017-1442-y. ISSN 1355-008X. PMID 29052180.

- Laganà, Antonio Simone; Vitagliano, Amerigo; Noventa, Marco; Ambrosini, Guido; D'Anna, Rosario (2018-08-04). "Myo-inositol supplementation reduces the amount of gonadotropins and length of ovarian stimulation in women undergoing IVF: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 298 (4): 675–684. doi:10.1007/s00404-018-4861-y. ISSN 1432-0711. PMID 30078122.

- Galazis N, Galazi M, Atiomo W (2011). "D-Chiro-inositol and its significance in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 27 (4): 256–62. doi:10.3109/09513590.2010.538099. PMID 21142777.

- Lim, Chi Eung Danforn; Ng, Rachel W. C.; Xu, Ke; Cheng, Nga Chong Lisa; Xue, Charlie C. L.; Liu, Jian Ping; Chen, Nini (2016-05-03). "Acupuncture for polycystic ovarian syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD007689. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007689.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 27136291.

- Wu, XK; Stener-Victorin, E; Kuang, HY; Ma, HL; Gao, JS; Xie, LZ; Hou, LH; Hu, ZX; Shao, XG; Ge, J; Zhang, JF; Xue, HY; Xu, XF; Liang, RN; Ma, HX; Yang, HW; Li, WL; Huang, DM; Sun, Y; Hao, CF; Du, SM; Yang, ZW; Wang, X; Yan, Y; Chen, XH; Fu, P; Ding, CF; Gao, YQ; Zhou, ZM; Wang, CC; Wu, TX; Liu, JP; Ng, EHY; Legro, RS; Zhang, H; PCOSAct Study, Group. (27 June 2017). "Effect of Acupuncture and Clomiphene in Chinese Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial". JAMA. 317 (24): 2502–2514. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.7217. PMC 5815063. PMID 28655015.

- Barry JA, Azizia MM, Hardiman PJ (2014). "Risk of endometrial, ovarian and breast cancer in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Hum. Reprod. Update. 20 (5): 748–758. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu012. PMC 4326303. PMID 24688118.

- New MI (1993). "Nonclassical congenital adrenal hyperplasia and the polycystic ovarian syndrome". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 687 (1): 193–205. Bibcode:1993NYASA.687..193N. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb43866.x. PMID 8323173.

- Hardiman P, Pillay OC, Atiomo W (2003). "Polycystic ovary syndrome and endometrial carcinoma". Lancet. 361 (9371): 1810–2. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13409-5. PMID 12781553.

- Mather KJ, Kwan F, Corenblum B (2000). "Hyperinsulinemia in polycystic ovary syndrome correlates with increased cardiovascular risk independent of obesity". Fertil. Steril. 73 (1): 150–6. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(99)00468-9. PMID 10632431.

- Moran LJ, Misso ML, Wild RA, Norman RJ (2010). "Impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Hum. Reprod. Update. 16 (4): 347–63. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq001. PMID 20159883.

- Barry JA, Kuczmierczyk AR, Hardiman PJ (2011). "Anxiety and depression in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Hum. Reprod. 26 (9): 2442–51. doi:10.1093/humrep/der197. PMID 21725075.

- de Groot PC, Dekkers OM, Romijn JA, Dieben SW, Helmerhorst FM (2011). "PCOS, coronary heart disease, stroke and the influence of obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Hum. Reprod. Update. 17 (4): 495–500. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr001. PMID 21335359.

- Goldenberg N, Glueck C (2008). "Medical therapy in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome before and during pregnancy and lactation". Minerva Ginecol. 60 (1): 63–75. PMID 18277353.

- Boomsma CM, Fauser BC, Macklon NS (2008). "Pregnancy complications in women with polycystic ovary syndrome". Semin. Reprod. Med. 26 (1): 072–084. doi:10.1055/s-2007-992927. PMID 18181085.

- Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. (2012). "Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2163–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMC 6350784. PMID 23245607.

- McLuskie, Isabel; Newth, Aisha (12 January 2017). "New diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome". BMJ. 356: i6456. doi:10.1136/bmj.i6456. hdl:10044/1/44217. PMID 28082338.

- Polson DW, Adams J, Wadsworth J, Franks S (1988). "Polycystic ovaries—a common finding in normal women". Lancet. 1 (8590): 870–2. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91612-1. PMID 2895373.

- Clayton RN, Ogden V, Hodgkinson J, Worswick L, Rodin DA, Dyer S, Meade TW (1992). "How common are polycystic ovaries in normal women and what is their significance for the fertility of the population?". Clin. Endocrinol. 37 (2): 127–34. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb02296.x. PMID 1395063.

- Farquhar CM, Birdsall M, Manning P, Mitchell JM, France JT (1994). "The prevalence of polycystic ovaries on ultrasound scanning in a population of randomly selected women". Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 34 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.1994.tb01041.x. PMID 8053879.

- van Santbrink EJ, Hop WC, Fauser BC (1997). "Classification of normogonadotropic infertility: polycystic ovaries diagnosed by ultrasound versus endocrine characteristics of polycystic ovary syndrome". Fertil. Steril. 67 (3): 452–8. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(97)80068-4. PMID 9091329.

- Hardeman J, Weiss BD (2014). "Intrauterine devices: an update". Am Fam Physician. 89 (6): 445–50. PMID 24695563.

- Azziz, Ricardo; Marin, Catherine; Hoq, Lalima; Badamgarav, Enkhe; Song, Paul (1 August 2005). "Health Care-Related Economic Burden of the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome during the Reproductive Life Span". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 90 (8): 4650–4658. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-0628. PMID 15944216.

- "RCDC Estimates of Funding for Various Research, Condition, and Disease Categories (RCDC)". NIH. NIH. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Polycystic ovary syndrome. |