Polyarteritis nodosa

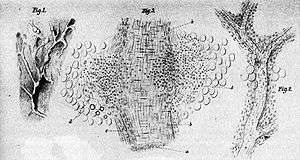

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), is a systemic necrotizing inflammation of blood vessels (vasculitis) affecting medium-sized muscular arteries, typically involving the arteries of the kidneys and other internal organs but generally sparing the lungs' circulation.[3] Polyarteritis nodosa may be present in infants.[4] In polyarteritis nodosa, small aneurysms are strung like the beads of a rosary,[5] therefore making "rosary sign" an important diagnostic feature of the vasculitis.[6] PAN is sometimes associated with infection by the hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus.[7]

| Polyarteritis Nodosa | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Panarteritis nodosa,[1] Periarteritis nodosa,[1] Kussmaul disease, or Kussmaul-Maier disease,[2] |

| |

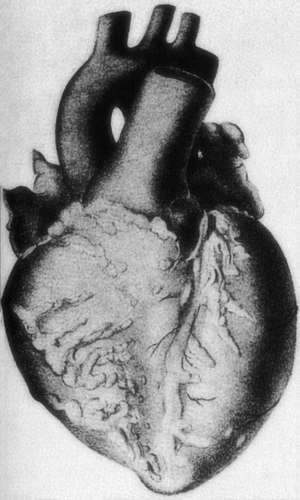

| Polyarteritis nodosa: Macroscopic specimen of the heart with abundant adipose tissue and nodular thickened coronary vessels | |

| Specialty | Immunology, rheumatology |

PAN is a rare disease.[7] With treatment, five-year survival is 80%; without treatment, five-year survival is 13%. Death is often a consequence of kidney failure, myocardial infarction, or stroke.[8]

Signs and symptoms

PAN may affect nearly every organ system and thus it can present with a broad array of signs and symptoms.[7] These manifestations result from ischemic damage to affected organs, often the skin, heart, kidneys, and nervous system. Constitutional symptoms are seen in up to 90% of affected individuals and include fever, fatigue, weakness, loss of appetite, and unintentional weight loss.[7] Muscle and joint aches are common.[7] The skin may show rashes, swelling, necrotic ulcers, and subcutaneous nodules (lumps).[7] Skin manifestations of PAN include palpable purpura and livedo reticularis in some individuals.[7] Abdominal pain may also be seen.

Nerve involvement may cause sensory changes with numbness, pain, burning, and weakness (peripheral neuropathy). Peripheral nerves are often affected and this most commonly presents as mononeuritis multiplex, which is the most common neurologic sign of PAN.[7] Central nervous system involvement may cause strokes or seizures. Kidney involvement is common and often leads to death of parts of the kidney though kidney filtration function is often preserved.[7] Involvement of the renal artery, which supplies the kidneys with highly oxygenated blood, often leads to high blood pressure in about one-third of cases.[7] deposition of protein or blood in the urine may also be seen.[7] Involvement of the arteries of the heart may cause a heart attack, heart failure, and inflammation of the sac around the heart (pericarditis).

Complications

- Stroke[7]

- Heart failure due to cardiomyopathy and pericarditis[7]

- Intestinal necrosis and perforation[9]

Causes

There is no association with ANCA,[7] but about 30% of people with PAN have chronic hepatitis B and deposits containing HBsAg-HBsAb complexes in affected blood vessels, indicating an immune complex–mediated cause in that subset. Infection with the Hepatitis C virus and HIV are occasionally discovered in people affected by PAN.[7] PAN has also been associated with underlying hairy cell leukemia. The cause remains unknown in the remaining cases; there may be causal and clinical distinctions between classic idiopathic PAN, the cutaneous forms of PAN, and PAN associated with chronic hepatitis.[3] In children, cutaneous PAN is frequently associated with streptococcal infections, and positive streptococcal serology is included in the diagnostic criteria.[10]

Diagnosis

No specific lab tests exist for diagnosing polyarteritis nodosa. Diagnosis is generally based on the physical examination and a few laboratory studies that help confirm the diagnosis:

- CBC (may demonstrate an elevated white blood count)

- ESR (elevated)

- Perinuclear pattern of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) - not associated with "classic" polyarteritis nodosa, but is present in a form of the disease affecting smaller blood vessels, known as microscopic polyangiitis or leukocytoclastic angiitis

- Tissue biopsy (reveals inflammation in small arteries, called arteritis)

- Elevated C-reactive protein

A patient is said to have polyarteritis nodosa if he or she has three of the 10 signs known as the 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)[11] criteria, when a radiographic or pathological diagnosis of vasculitis is made:

- Weight loss greater than/equal to 4.5 kg

- Livedo reticularis (a mottled purplish skin discoloration over the extremities or torso)

- Testicular pain or tenderness (occasionally, a site biopsied for diagnosis)

- Muscle pain, weakness, or leg tenderness

- Nerve disease (either single or multiple)

- Diastolic blood pressure greater than 90 mmHg (high blood pressure)

- Elevated kidney blood tests (BUN greater than 40 mg/dL or creatinine greater than 1.5 mg/dL)

- Hepatitis B (not C) virus tests positive (for surface antigen or antibody)

- Arteriogram (angiogram) showing the arteries that are dilated (aneurysms) or constricted by the blood vessel inflammation

- Biopsy of tissue showing the arteritis (typically inflamed arteries):[12] The sural nerve is a frequent location for the biopsy.

In polyarteritis nodosa, small aneurysms are strung like the beads of a rosary,[5] therefore making "rosary sign" an important diagnostic feature of the vasculitis.[6] The 1990 ACR criteria were designed for classification purposes only. Nevertheless, their good discriminatory performances, indicated by the initial ACR analysis, suggested their potential usefulness for diagnostic purposes as well. Subsequent studies did not confirm their diagnostic utility, demonstrating a significant dependence of their discriminative abilities on the prevalence of the various vasculitides in the analyzed populations. Recently, an original study, combining the analysis of more than 100 items used to describe patients' characteristics in a large sample of vasculitides with a computer simulation technique designed to test the potential diagnostic utility of the various criteria, proposed a set of eight positively or negatively discriminating items to be used as a screening tool for diagnosis in patients suspected of systemic vasculitis.[13]

Differential diagnosis

Polyarteritis nodosa rarely affects the blood vessels of the lungs and this feature can help to differentiate it from other vasculitides, which may have similar signs and symptoms (e.g., granulomatosis with polyangiitis or microscopic polyangiitis).[7]

Treatment

Treatment involves medications to suppress the immune system, including prednisone and cyclophosphamide. When present, underlying hepatitis B virus infection should be immediately treated. In some cases, methotrexate or leflunomide may be helpful.[14] Some patients have also noticed a remission phase when a four-dose infusion of rituximab is used before the leflunomide treatment is begun. Therapy results in remissions or cures in 90% of cases. Untreated, the disease is fatal in most cases. The most serious associated conditions generally involve the kidneys and gastrointestinal tract. A fatal course usually involves gastrointestinal bleeding, infection, myocardial infarction, and/or kidney failure.[15]

In case of remission, about 60% experience relapse within five years.[16] In cases caused by hepatitis B virus, however, recurrence rate is only around 6%.[17]

Epidemiology

The condition affects adults more frequently than children and males more frequently than females.[7] Most cases occur between the ages of 40 and 60.[7] Polyarteritis nodosa is more common in people with hepatitis B infection.[7]

History

The medical eponyms (Kussmaul disease or Kussmaul-Maier disease) reflect the seminal description of the disease in the medical literature by Adolph Kussmaul and Rudolf Robert Maier.

In popular media

The 1956 film Bigger Than Life featured the protagonist being diagnosed with polyarteritis nodosa.

References

- Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- synd/764 at Who Named It?

- Kumar, Vinay; K. Abbas, Abul; C. Aster, Jon (2015). Robbins and Cotran: Pathologic Basis of Disease (9th ed.). Elsevier. p. 509. ISBN 978-1-4557-2613-4.

- Person, A, Donald (2006-06-15). "Infantile Polyarteritis Nodosa". eMedicine. WebMD. Retrieved 24 December 2009.

- Keen, William. Surgery, Volume 5. W. B. Saunders. p. 243.

- Greenson, Joel K.; Montgomery, Elizabeth A.; Polydorides, Alexandros D. (1 September 2009). Diagnostic Pathology: Gastrointestinal: Published by Amirsys. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-931884-26-6. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- Forbess, L; Bannykh, S (2015). "Polyarteritis Nodosa". Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America. 41 (1): 33–46, vii. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2014.09.005. PMID 25399938.

- Russell Goodman; Paul F. Dellaripa; Amy Leigh Miller; Joseph Loscalzo (January 2, 2014). "An Unusual Case of Abdominal Pain". N Engl J Med. 370 (1): 70–75. doi:10.1056/NEJMcps1215559. PMID 24382068.

- Ebert, Ellen C.; Hagspiel, Klaus D.; Nagar, Michael; Schlesinger, Naomi (2008). "Gastrointestinal Involvement in Polyarteritis Nodosa". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 6 (9): 960–966. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2008.04.004. ISSN 1542-3565. PMID 18585977.

- Sarah Ringold; Carol A Wallace (May 1, 2010). "Evolution of paediatric-specific vasculitis classification criteria". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 69 (5): 785–86. doi:10.1136/ard.2009.127886. PMID 20388739.

- American College of Rheumatology

- Shiel, Jr., William C, http://www.medicinenet.com/polyarteritis_nodosa/article.htm

- Henegar, Corneliu; Pagnoux, Christian; Puéchal, Xavier; Zucker, Jean-Daniel; Bar-Hen, Avner; Guern, Véronique Le; Saba, Mona; Bagnères, Denis; Meyer, Olivier; Guillevin, Loïc (1 May 2008). "A paradigm of diagnostic criteria for polyarteritis nodosa: Analysis of a series of 949 patients with vasculitides". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 58 (5): 1528–1538. doi:10.1002/art.23470. PMID 18438816.

- Boehm, Ingrid; Bauer, R (1 February 2000). "Low-Dose Methotrexate Controls a Severe Form of Polyarteritis Nodosa". Archives of Dermatology. 136 (2): 167–9. doi:10.1001/archderm.136.2.167. PMID 10677090.

- Giannini, AJ; Black, HR. Psychiatric, Psychogenic and Somatopsychic Disorders Handbook. Garden City, NY. Medical Examination Publishing, 1978. Pp. 219–220. ISBN 0-87488-596-5

- Selga, D.; Mohammad, A.; Sturfelt, G.; Segelmark, M. (2006). "Polyarteritis nodosa when applying the Chapel Hill nomenclature--a descriptive study on ten patients". Rheumatology. 45 (10): 1276–1281. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kel091. PMID 16595516., Entry in Polyarteritis Nodosa Follow-up article

- Guillevin, L.; Lhote, F.; Cohen, P.; Sauvaget, F.; Jarrousse, B.; Lortholary, O.; Noël, L.; Trépo, C. (1995). "Polyarteritis nodosa related to hepatitis B virus. A prospective study with long-term observation of 41 patients". Medicine. 74 (5): 238–253. doi:10.1097/00005792-199509000-00002. PMID 7565065. , Entry in Polyarteritis Nodosa Follow-up article

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |