Pneumothorax

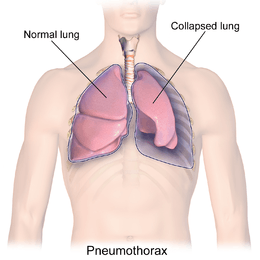

A pneumothorax is an abnormal collection of air in the pleural space between the lung and the chest wall.[3] Symptoms typically include sudden onset of sharp, one-sided chest pain and shortness of breath.[2] In a minority of cases the amount of air in the chest increases when a one-way valve is formed by an area of damaged tissue, leading to a tension pneumothorax.[3] This condition can cause a steadily worsening oxygen shortage and low blood pressure.[3] Unless reversed by effective treatment this can be fatal.[3] Very rarely both lungs may be affected by a pneumothorax.[6] It is often called a collapsed lung, although that term may also refer to atelectasis.[1]

| Pneumothorax | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Collapsed lung[1] |

| |

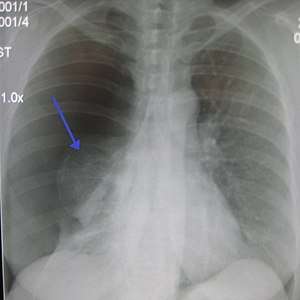

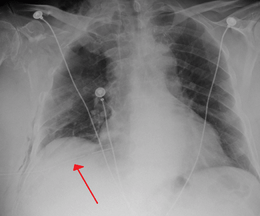

| A large right-sided spontaneous pneumothorax (left in the image). An arrow indicates the edge of the collapsed lung | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology, thoracic surgery |

| Symptoms | Chest pain, shortness of breath, tiredness[2] |

| Usual onset | Sudden[3] |

| Causes | Unknown, trauma[3] |

| Risk factors | COPD, tuberculosis, smoking[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Chest X-ray, ultrasound, CT scan[5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Lung bullae,[3] hemothorax[2] |

| Prevention | Stopping smoking[3] |

| Treatment | conservative, needle aspiration, chest tube, pleurodesis[3] |

| Frequency | 20 per 100,000 per year[3][5] |

A primary spontaneous pneumothorax is one that occurs without an apparent cause and in the absence of significant lung disease.[3] A secondary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs in the presence of existing lung disease.[3][7] Smoking increases the risk of primary spontaneous pneumothorax, while the main underlying causes for secondary pneumothorax are COPD, asthma, and tuberculosis.[3][4] A pneumothorax can also be caused by physical trauma to the chest (including a blast injury) or as a complication of a healthcare intervention, in which case it is called a traumatic pneumothorax.[8][9]

Diagnosis of a pneumothorax by physical examination alone can be difficult (particularly in smaller pneumothoraces).[10] A chest X-ray, computed tomography (CT) scan, or ultrasound is usually used to confirm its presence.[5] Other conditions that can result in similar symptoms include a hemothorax (buildup of blood in the pleural space), pulmonary embolism, and heart attack.[2][11] A large bulla may look similar on a chest X-ray.[3]

A small spontaneous pneumothorax will typically resolve without treatment and requires only monitoring.[3] This approach may be most appropriate in people who have no underlying lung disease.[3] In a larger pneumothorax, or if there is shortness of breath, the air may be removed with a syringe or a chest tube connected to a one-way valve system.[3] Occasionally, surgery may be required if tube drainage is unsuccessful, or as a preventive measure, if there have been repeated episodes.[3] The surgical treatments usually involve pleurodesis (in which the layers of pleura are induced to stick together) or pleurectomy (the surgical removal of pleural membranes).[3] About 17–23 cases of pneumothorax occur per 100,000 people per year.[3][5] They are more common in men than women.[3]

Signs and symptoms

A primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP) tends to occur in a young adult without underlying lung problems, and usually causes limited symptoms. Chest pain and sometimes mild breathlessness are the usual predominant presenting features.[12][13] People who are affected by a PSP are often unaware of the potential danger and may wait several days before seeking medical attention.[14] PSPs more commonly occur during changes in atmospheric pressure, explaining to some extent why episodes of pneumothorax may happen in clusters.[13] It is rare for a PSP to cause a tension pneumothorax.[12]

Secondary spontaneous pneumothoraces (SSPs), by definition, occur in individuals with significant underlying lung disease. Symptoms in SSPs tend to be more severe than in PSPs, as the unaffected lungs are generally unable to replace the loss of function in the affected lungs. Hypoxemia (decreased blood-oxygen levels) is usually present and may be observed as cyanosis (blue discoloration of the lips and skin). Hypercapnia (accumulation of carbon dioxide in the blood) is sometimes encountered; this may cause confusion and – if very severe – may result in comas. The sudden onset of breathlessness in someone with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cystic fibrosis, or other serious lung diseases should therefore prompt investigations to identify the possibility of a pneumothorax.[12][14]

Traumatic pneumothorax most commonly occurs when the chest wall is pierced, such as when a stab wound or gunshot wound allows air to enter the pleural space, or because some other mechanical injury to the lung compromises the integrity of the involved structures. Traumatic pneumothoraces have been found to occur in up to half of all cases of chest trauma, with only rib fractures being more common in this group. The pneumothorax can be occult (not readily apparent) in half of these cases, but may enlarge – particularly if mechanical ventilation is required.[13] They are also encountered in people already receiving mechanical ventilation for some other reason.[13]

Upon physical examination, breath sounds (heard with a stethoscope) may be diminished on the affected side, partly because air in the pleural space dampens the transmission of sound. Measures of the conduction of vocal vibrations to the surface of the chest may be altered. Percussion of the chest may be perceived as hyperresonant (like a booming drum), and vocal resonance and tactile fremitus can both be noticeably decreased. Importantly, the volume of the pneumothorax may not be well correlated with the intensity of the symptoms experienced by the victim,[14] and physical signs may not be apparent if the pneumothorax is relatively small.[13][14]

Tension pneumothorax

Although multiple definitions exist, a tension pneumothorax is generally considered to be present when a pneumothorax (primary spontaneous, secondary spontaneous, or traumatic) leads to significant impairment of respiration and/or blood circulation.[15] Tension pneumothorax tends to occur in clinical situations such as ventilation, resuscitation, trauma, or in people with lung disease.[14]

The most common findings in people with tension pneumothorax are chest pain and respiratory distress, often with an increased heart rate (tachycardia) and rapid breathing (tachypnea) in the initial stages. Other findings may include quieter breath sounds on one side of the chest, low oxygen levels and blood pressure, and displacement of the trachea away from the affected side. Rarely, there may be cyanosis (bluish discoloration of the skin due to low oxygen levels), altered level of consciousness, a hyperresonant percussion note on examination of the affected side with reduced expansion and decreased movement, pain in the epigastrium (upper abdomen), displacement of the apex beat (heart impulse), and resonant sound when tapping the sternum.[15] This is a medical emergency and may require immediate treatment without further investigations (see below).[14][15]

Tension pneumothorax may also occur in someone who is receiving mechanical ventilation, in which case it may be difficult to spot as the person is typically receiving sedation; it is often noted because of a sudden deterioration in condition.[15] Recent studies have shown that the development of tension features may not always be as rapid as previously thought. Deviation of the trachea to one side and the presence of raised jugular venous pressure (distended neck veins) are not reliable as clinical signs.[15]

Cause

Primary spontaneous

Spontaneous pneumothoraces are divided into two types: primary, which occurs in the absence of known lung disease, and secondary, which occurs in someone with underlying lung disease.[16] The cause of primary spontaneous pneumothorax is unknown, but established risk factors include male sex, smoking, and a family history of pneumothorax.[17] Smoking either cannabis or tobacco increases the risk.[3] The various suspected underlying mechanisms are discussed below.[12][13]

Secondary spontaneous

Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs in the setting of a variety of lung diseases. The most common is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which accounts for approximately 70% of cases.[17] Known lung diseases that may significantly increase the risk for pneumothorax are

| Type | Causes |

|---|---|

| Diseases of the airways[12] | COPD (especially when emphysema and lung bullae are present), acute severe asthma, cystic fibrosis |

| Infections of the lung[12] | Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia |

| Interstitial lung disease[12] | Sarcoidosis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, histiocytosis X, lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) |

| Connective tissue diseases[12] | Rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, polymyositis and dermatomyositis, systemic sclerosis, Marfan's syndrome and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome |

| Cancer[12] | Lung cancer, sarcomas involving the lung |

| Miscellaneous[13] | Catamenial pneumothorax (associated with the menstrual cycle and related to endometriosis in the chest) |

In children, additional causes include measles, echinococcosis, inhalation of a foreign body, and certain congenital malformations (congenital pulmonary airway malformation and congenital lobar emphysema).[18]

11.5% of people with a spontaneous pneumothorax have a family member who has previously experienced a pneumothorax. The hereditary conditions – Marfan syndrome, homocystinuria, Ehlers–Danlos syndromes, alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency (which leads to emphysema), and Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome – have all been linked to familial pneumothorax.[19] Generally, these conditions cause other signs and symptoms as well, and pneumothorax is not usually the primary finding.[19] Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome is caused by mutations in the FLCN gene (located at chromosome 17p11.2), which encodes a protein named folliculin.[18][19] FLCN mutations and lung lesions have also been identified in familial cases of pneumothorax where other features of Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome are absent.[18] In addition to the genetic associations, the HLA haplotype A2B40 is also a genetic predisposition to PSP.[20][21]

Traumatic

A traumatic pneumothorax may result from either blunt trauma or penetrating injury to the chest wall.[13] The most common mechanism is due to the penetration of sharp bony points at a new rib fracture, which damages lung tissue.[17] Traumatic pneumothorax may also be observed in those exposed to blasts, even though there is no apparent injury to the chest.[9]

They may be classified as "open" or "closed". In an open pneumothorax, there is a passage from the external environment into the pleural space through the chest wall. When air is drawn into the pleural space through this passageway, it is known as a "sucking chest wound". A closed pneumothorax is when the chest wall remains intact.[22]

Medical procedures, such as the insertion of a central venous catheter into one of the chest veins or the taking of biopsy samples from lung tissue, may lead to pneumothorax. The administration of positive pressure ventilation, either mechanical ventilation or non-invasive ventilation, can result in barotrauma (pressure-related injury) leading to a pneumothorax.[13]

Divers who breathe from an underwater apparatus are supplied with breathing gas at ambient pressure, which results in their lungs containing gas at higher than atmospheric pressure. Divers breathing compressed air (such as when scuba diving) may suffer a pneumothorax as a result of barotrauma from ascending just 1 metre (3 ft) while breath-holding with their lungs fully inflated.[23] An additional problem in these cases is that those with other features of decompression sickness are typically treated in a diving chamber with hyperbaric therapy; this can lead to a small pneumothorax rapidly enlarging and causing features of tension.[23]

Mechanism

The thoracic cavity is the space inside the chest that contains the lungs, heart, and numerous major blood vessels. On each side of the cavity, a pleural membrane covers the surface of lung (visceral pleura) and also lines the inside of the chest wall (parietal pleura). Normally, the two layers are separated by a small amount of lubricating serous fluid. The lungs are fully inflated within the cavity because the pressure inside the airways is higher than the pressure inside the pleural space. Despite the low pressure in the pleural space, air does not enter it because there are no natural connections to an air-containing passage, and the pressure of gases in the bloodstream is too low for them to be forced into the pleural space.[13] Therefore, a pneumothorax can only develop if air is allowed to enter, through damage to the chest wall or damage to the lung itself, or occasionally because microorganisms in the pleural space produce gas.[13]

Chest-wall defects are usually evident in cases of injury to the chest wall, such as stab or bullet wounds ("open pneumothorax"). In secondary spontaneous pneumothoraces, vulnerabilities in the lung tissue are caused by a variety of disease processes, particularly by rupturing of bullae (large air-containing lesions) in cases of severe emphysema. Areas of necrosis (tissue death) may precipitate episodes of pneumothorax, although the exact mechanism is unclear.[12] Primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP) has for many years been thought to be caused by "blebs" (small air-filled lesions just under the pleural surface), which were presumed to be more common in those classically at risk of pneumothorax (tall males) due to mechanical factors. In PSP, blebs can be found in 77% of cases, compared to 6% in the general population without a history of PSP.[24] As these healthy subjects do not all develop a pneumothorax later, the hypothesis may not be sufficient to explain all episodes; furthermore, pneumothorax may recur even after surgical treatment of blebs.[13] It has therefore been suggested that PSP may also be caused by areas of disruption (porosity) in the pleural layer, which are prone to rupture.[12][13][24] Smoking may additionally lead to inflammation and obstruction of small airways, which account for the markedly increased risk of PSPs in smokers.[14] Once air has stopped entering the pleural cavity, it is gradually reabsorbed.[14]

Tension pneumothorax occurs when the opening that allows air to enter the pleural space functions as a one-way valve, allowing more air to enter with every breath but none to escape. The body compensates by increasing the respiratory rate and tidal volume (size of each breath), worsening the problem. Unless corrected, hypoxia (decreased oxygen levels) and respiratory arrest eventually follow.[15]

Diagnosis

The symptoms of pneumothorax can be vague and inconclusive, especially in those with a small PSP; confirmation with medical imaging is usually required.[14] In contrast, tension pneumothorax is a medical emergency and may be treated before imaging – especially if there is severe hypoxia, very low blood pressure, or an impaired level of consciousness. In tension pneumothorax, X-rays are sometimes required if there is doubt about the anatomical location of the pneumothorax.[15][17]

Chest X-ray

A plain chest radiograph, ideally with the X-ray beams being projected from the back (posteroanterior, or "PA"), and during maximal inspiration (holding one's breath), is the most appropriate first investigation.[25] It is not believed that routinely taking images during expiration would confer any benefit.[26] Still, they may be useful in the detection of a pneumothorax when clinical suspicion is high but yet an inspiratory radiograph appears normal.[27] Also, if the PA X-ray does not show a pneumothorax but there is a strong suspicion of one, lateral X-rays (with beams projecting from the side) may be performed, but this is not routine practice.[14][18]

Anteroposterior inspired X-ray, showing subtle left-sided pneumothorax caused by port insertion

Anteroposterior inspired X-ray, showing subtle left-sided pneumothorax caused by port insertion Lateral inspired X-ray at the same time, more clearly showing the pneumothorax posteriorly in this case

Lateral inspired X-ray at the same time, more clearly showing the pneumothorax posteriorly in this case Anteroposterior expired X-ray at the same time, more clearly showing the pneumothorax in this case

Anteroposterior expired X-ray at the same time, more clearly showing the pneumothorax in this case

It is not unusual for the mediastinum (the structure between the lungs that contains the heart, great blood vessels and large airways) to be shifted away from the affected lung due to the pressure differences. This is not equivalent to a tension pneumothorax, which is determined mainly by the constellation of symptoms, hypoxia, and shock.[13]

The size of the pneumothorax (i.e. the volume of air in the pleural space) can be determined with a reasonable degree of accuracy by measuring the distance between the chest wall and the lung. This is relevant to treatment, as smaller pneumothoraces may be managed differently. An air rim of 2 cm means that the pneumothorax occupies about 50% of the hemithorax.[14] British professional guidelines have traditionally stated that the measurement should be performed at the level of the hilum (where blood vessels and airways enter the lung) with 2 cm as the cutoff,[14] while American guidelines state that the measurement should be done at the apex (top) of the lung with 3 cm differentiating between a "small" and a "large" pneumothorax.[28] The latter method may overestimate the size of a pneumothorax if it is located mainly at the apex, which is a common occurrence.[14] The various methods correlate poorly, but are the best easily available ways of estimating pneumothorax size.[14][18] CT scanning (see below) can provide a more accurate determination of the size of the pneumothorax, but its routine use in this setting is not recommended.[28]

Not all pneumothoraces are uniform; some only form a pocket of air in a particular place in the chest.[14] Small amounts of fluid may be noted on the chest X-ray (hydropneumothorax); this may be blood (hemopneumothorax).[13] In some cases, the only significant abnormality may be the "deep sulcus sign", in which the normally small space between the chest wall and the diaphragm appears enlarged due to the abnormal presence of fluid.[15]

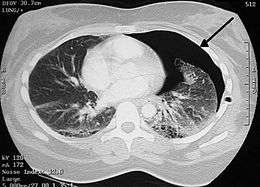

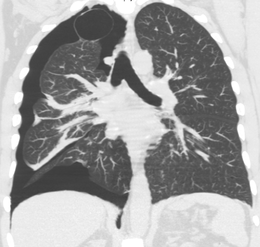

Computed tomography

A CT scan is not necessary for the diagnosis of pneumothorax, but it can be useful in particular situations. In some lung diseases, especially emphysema, it is possible for abnormal lung areas such as bullae (large air-filled sacs) to have the same appearance as a pneumothorax on chest X-ray, and it may not be safe to apply any treatment before the distinction is made and before the exact location and size of the pneumothorax is determined.[14] In trauma, where it may not be possible to perform an upright film, chest radiography may miss up to a third of pneumothoraces, while CT remains very sensitive.[17]

A further use of CT is in the identification of underlying lung lesions. In presumed primary pneumothorax, it may help to identify blebs or cystic lesions (in anticipation of treatment, see below), and in secondary pneumothorax it can help to identify most of the causes listed above.[14][18]

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is commonly used in the evaluation of people who have sustained physical trauma, for example with the FAST protocol.[29] Ultrasound may be more sensitive than chest X-rays in the identification of pneumothorax after blunt trauma to the chest.[30] Ultrasound may also provide a rapid diagnosis in other emergency situations, and allow the quantification of the size of the pneumothorax. Several particular features on ultrasonography of the chest can be used to confirm or exclude the diagnosis.[31][32]

Treatment

The treatment of pneumothorax depends on a number of factors, and may vary from discharge with early follow-up to immediate needle decompression or insertion of a chest tube. Treatment is determined by the severity of symptoms and indicators of acute illness, the presence of underlying lung disease, the estimated size of the pneumothorax on X-ray, and – in some instances – on the personal preference of the person involved.[14]

In traumatic pneumothorax, chest tubes are usually inserted. If mechanical ventilation is required, the risk of tension pneumothorax is greatly increased and the insertion of a chest tube is mandatory.[13][35] Any open chest wound should be covered with an airtight seal, as it carries a high risk of leading to tension pneumothorax. Ideally, a dressing called the "Asherman seal" should be utilized, as it appears to be more effective than a standard "three-sided" dressing. The Asherman seal is a specially designed device that adheres to the chest wall and, through a valve-like mechanism, allows air to escape but not to enter the chest.[36]

Tension pneumothorax is usually treated with urgent needle decompression. This may be required before transport to the hospital, and can be performed by an emergency medical technician or other trained professional.[15][36] The needle or cannula is left in place until a chest tube can be inserted.[15][36] If tension pneumothorax leads to cardiac arrest, needle decompression is performed as part of resuscitation as it may restore cardiac output.[37]

Conservative

Small spontaneous pneumothoraces do not always require treatment, as they are unlikely to proceed to respiratory failure or tension pneumothorax, and generally resolve spontaneously. This approach is most appropriate if the estimated size of the pneumothorax is small (defined as <50% of the volume of the hemithorax), there is no breathlessness, and there is no underlying lung disease.[18][28] It may be appropriate to treat a larger PSP conservatively if the symptoms are limited.[14] Admission to hospital is often not required, as long as clear instructions are given to return to hospital if there are worsening symptoms. Further investigations may be performed as an outpatient, at which time X-rays are repeated to confirm improvement, and advice given with regard to preventing recurrence (see below).[14] Estimated rates of resorption are between 1.25% and 2.2% the volume of the cavity per day. This would mean that even a complete pneumothorax would spontaneously resolve over a period of about 6 weeks.[14] There is, however, no high quality evidence comparing conservative to non conservative management.[38]

Secondary pneumothoraces are only treated conservatively if the size is very small (1 cm or less air rim) and there are limited symptoms. Admission to the hospital is usually recommended. Oxygen given at a high flow rate may accelerate resorption as much as fourfold.[14][39]

Aspiration

In a large PSP (>50%), or in a PSP associated with breathlessness, some guidelines recommend that reducing the size by aspiration is equally effective as the insertion of a chest tube. This involves the administration of local anesthetic and inserting a needle connected to a three-way tap; up to 2.5 liters of air (in adults) are removed. If there has been significant reduction in the size of the pneumothorax on subsequent X-ray, the remainder of the treatment can be conservative. This approach has been shown to be effective in over 50% of cases.[12][14][18] Compared to tube drainage, first-line aspiration in PSP reduces the number of people requiring hospital admission, without increasing the risk of complications.[40]

Aspiration may also be considered in secondary pneumothorax of moderate size (air rim 1–2 cm) without breathlessness, with the difference that ongoing observation in hospital is required even after a successful procedure.[14] American professional guidelines state that all large pneumothoraces – even those due to PSP – should be treated with a chest tube.[28] Moderately sized iatrogenic traumatic pneumothoraces (due to medical procedures) may initially be treated with aspiration.[13]

Chest tube

A chest tube (or intercostal drain) is the most definitive initial treatment of a pneumothorax. These are typically inserted in an area under the axilla (armpit) called the "safe triangle", where damage to internal organs can be avoided; this is delineated by a horizontal line at the level of the nipple and two muscles of the chest wall (latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major). Local anesthetic is applied. Two types of tubes may be used. In spontaneous pneumothorax, small-bore (smaller than 14 F, 4.7 mm diameter) tubes may be inserted by the Seldinger technique, and larger tubes do not have an advantage.[14][41] In traumatic pneumothorax, larger tubes (28 F, 9.3 mm) are used.[36]

Chest tubes are required in PSPs that have not responded to needle aspiration, in large SSPs (>50%), and in cases of tension pneumothorax. They are connected to a one-way valve system that allows air to escape, but not to re-enter, the chest. This may include a bottle with water that functions like a water seal, or a Heimlich valve. They are not normally connected to a negative pressure circuit, as this would result in rapid re-expansion of the lung and a risk of pulmonary edema ("re-expansion pulmonary edema"). The tube is left in place until no air is seen to escape from it for a period of time, and X-rays confirm re-expansion of the lung.[14][18][28]

If after 2–4 days there is still evidence of an air leak, various options are available. Negative pressure suction (at low pressures of –10 to –20 cmH2O) at a high flow rate may be attempted, particularly in PSP; it is thought that this may accelerate the healing of the leak. Failing this, surgery may be required, especially in SSP.[14]

Chest tubes are used first-line when pneumothorax occurs in people with AIDS, usually due to underlying pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), as this condition is associated with prolonged air leakage. Bilateral pneumothorax (pneumothorax on both sides) is relatively common in people with pneumocystis pneumonia, and surgery is often required.[14]

It is possible for a person with a chest tube to be managed in an ambulatory care setting by using a Heimlich valve, although research to demonstrate the equivalence to hospitalization has been of limited quality.[42]

Pleurodesis and surgery

Pleurodesis is a procedure that permanently eliminates the pleural space and attaches the lung to the chest wall. No long-term study (20 years or more) has been performed on its consequences. Good results in the short term are achieved with a thoracotomy (surgical opening of the chest) with identification of any source of air leakage and stapling of blebs followed by pleurectomy (stripping of the pleural lining) of the outer pleural layer and pleural abrasion (scraping of the pleura) of the inner layer. During the healing process, the lung adheres to the chest wall, effectively obliterating the pleural space. Recurrence rates are approximately 1%.[12][14] Post-thoracotomy pain is relatively common.

A less invasive approach is thoracoscopy, usually in the form of a procedure called video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). The results from VATS-based pleural abrasion are slightly worse than those achieved using thoracotomy in the short term, but produce smaller scars in the skin.[12][14] Compared to open thoracotomy, VATS offers a shorter in-hospital stays, less need for postoperative pain control, and a reduced risk of lung problems after surgery.[14] VATS may also be used to achieve chemical pleurodesis; this involves insufflation of talc, which activates an inflammatory reaction that causes the lung to adhere to the chest wall.[12][14]

If a chest tube is already in place, various agents may be instilled through the tube to achieve chemical pleurodesis, such as talc, tetracycline, minocycline or doxycycline. Results of chemical pleurodesis tend to be worse than when using surgical approaches,[12][14] but talc pleurodesis has been found to have few negative long-term consequences in younger people.[12]

Aftercare

If pneumothorax occurs in a smoker, this is considered an opportunity to emphasize the markedly increased risk of recurrence in those who continue to smoke, and the many benefits of smoking cessation.[14] It may be advisable for someone to remain off work for up to a week after a spontaneous pneumothorax. If the person normally performs heavy manual labor, several weeks may be required. Those who have undergone pleurodesis may need two to three weeks off work to recover.[43]

Air travel is discouraged for up to seven days after complete resolution of a pneumothorax if recurrence does not occur.[14] Underwater diving is considered unsafe after an episode of pneumothorax unless a preventative procedure has been performed. Professional guidelines suggest that pleurectomy be performed on both lungs and that lung function tests and CT scan normalize before diving is resumed.[14][28] Aircraft pilots may also require assessment for surgery.[14]

Prevention

A preventative procedure (thoracotomy or thoracoscopy with pleurodesis) may be recommended after an episode of pneumothorax, with the intention to prevent recurrence. Evidence on the most effective treatment is still conflicting in some areas, and there is variation between treatments available in Europe and the US.[12] Not all episodes of pneumothorax require such interventions; the decision depends largely on estimation of the risk of recurrence. These procedures are often recommended after the occurrence of a second pneumothorax.[44] Surgery may need to be considered if someone has experienced pneumothorax on both sides ("bilateral"), sequential episodes that involve both sides, or if an episode was associated with pregnancy.[14]

Epidemiology

The annual age-adjusted incidence rate (AAIR) of PSP is thought to be three to six times as high in males as in females. Fishman[45][46] cites AAIR's of 7.4 and 1.2 cases per 100,000 person-years in males and females, respectively. Significantly above-average height is also associated with increased risk of PSP – in people who are at least 76 inches (1.93 meters) tall, the AAIR is about 200 cases per 100,000 person-years. Slim build also seems to increase the risk of PSP.[45]

The risk of contracting a first spontaneous pneumothorax is elevated among male and female smokers by factors of approximately 22 and 9, respectively, compared to matched non-smokers of the same sex.[47] Individuals who smoke at higher intensity are at higher risk, with a "greater-than-linear" effect; men who smoke 10 cigarettes per day have an approximate 20-fold increased risk over comparable non-smokers, while smokers consuming 20 cigarettes per day show an estimated 100-fold increase in risk.[45]

In secondary spontaneous pneumothorax, the estimated annual AAIR is 6.3 and 2.0 cases per 100,000 person-years for males and females,[20][48] respectively, with the risk of recurrence depending on the presence and severity of any underlying lung disease. Once a second episode has occurred, there is a high likelihood of subsequent further episodes.[12] The incidence in children has not been well studied,[18] but is estimated to be between 5 and 10 cases per 100,000 person-years.[49]

Death from pneumothorax is very uncommon (except in tension pneumothoraces). British statistics show an annual mortality rate of 1.26 and 0.62 deaths per million person-years in men and women, respectively.[14] A significantly increased risk of death is seen in older victims and in those with secondary pneumothoraces.[12]

History

An early description of traumatic pneumothorax secondary to rib fractures appears in Imperial Surgery by Turkish surgeon Şerafeddin Sabuncuoğlu (1385–1468), which also recommends a method of simple aspiration.[50]

Pneumothorax was described in 1803 by Jean Marc Gaspard Itard, a student of René Laennec, who provided an extensive description of the clinical picture in 1819.[51] While Itard and Laennec recognized that some cases were not due to tuberculosis (then the most common cause), the concept of spontaneous pneumothorax in the absence of tuberculosis (primary pneumothorax) was reintroduced by the Danish physician Hans Kjærgaard in 1932.[14][24][52] In 1941, the surgeons Tyson and Crandall introduced pleural abrasion for the treatment of pneumothorax.[14][53]

Prior to the advent of anti-tuberculous medications, pneumothoraces were intentionally caused by healthcare providers in people with tuberculosis in an effort to collapse a lobe, or entire lung, around a cavitating lesion. This was known as "resting the lung". It was introduced by the Italian surgeon Carlo Forlanini in 1888, and publicized by the American surgeon John Benjamin Murphy in the early 20th century (after discovering the same procedure independently). Murphy used the (then) recently discovered X-ray technology to create pneumothoraces of the correct size.[54]

Etymology

The word pneumothorax is from the Greek pneumo- meaning air and thorax meaning chest.[55] Its plural is pneumothoraces.

Other animals

Non-human animals may experience both spontaneous and traumatic pneumothorax. Spontaneous pneumothorax is, as in humans, classified as primary or secondary, while traumatic pneumothorax is divided into open and closed (with or without chest wall damage).[56] The diagnosis may be apparent to the veterinary physician because the animal exhibits difficulty breathing in, or has shallow breathing. Pneumothoraces may arise from lung lesions (such as bullae) or from trauma to the chest wall.[57] In horses, traumatic pneumothorax may involve both hemithoraces, as the mediastinum is incomplete and there is a direct connection between the two halves of the chest.[58] Tension pneumothorax – the presence of which may be suspected due to rapidly deteriorating heart function, absent lung sounds throughout the thorax, and a barrel-shaped chest – is treated with an incision in the animal's chest to relieve the pressure, followed by insertion of a chest tube.[59]

References

- Orenstein, David M. (2004). Cystic Fibrosis: A Guide for Patient and Family. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 62. ISBN 9780781741521. Archived from the original on 31 October 2016.

- "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Pleurisy and Other Pleural Disorders". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. 21 September 2011. Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- Bintcliffe, Oliver; Maskell, Nick (8 May 2014). "Spontaneous pneumothorax". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 348: g2928. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2928. PMID 24812003.

- "What Causes Pleurisy and Other Pleural Disorders?". NHLBI. 21 September 2011. Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- Chen, Lin; Zhang, Zhongheng (August 2015). "Bedside ultrasonography for diagnosis of pneumothorax". Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery. 5 (4): 618–23. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2015.05.04. PMC 4559988. PMID 26435925.

- Morjaria, Jaymin B.; Lakshminarayana, Umesh B.; Liu-Shiu-Cheong, P.; Kastelik, Jack A. (November 2014). "Pneumothorax: a tale of pain or spontaneity". Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. 5 (6): 269–73. doi:10.1177/2040622314551549. PMC 4205574. PMID 25364493.

- Weinberger, S; Cockrill, B; Mandel, J (2019). Principles of Pulmonary Medicine (7th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 215–216. ISBN 9780323523714.

- Slade, Mark (December 2014). "Management of pneumothorax and prolonged air leak". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 35 (6): 706–14. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1395502. PMID 25463161.

- Wolf, Stephen J.; Bebarta, Vikhyat S.; Bonnett, Carl J.; Pons, Peter T.; Cantrill, Stephen V. (August 2009). "Blast injuries". The Lancet. 374 (9687): 405–15. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60257-9. PMID 19631372.

- Yarmus, Lonny; Feller-Kopman, David (April 2012). "Pneumothorax in the critically ill patient". Chest. 141 (4): 1098–105. doi:10.1378/chest.11-1691. PMID 22474153.

- Peters, Jessica Radin; (MD.), Daniel Egan (2006). Blueprints Emergency Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 44. ISBN 9781405104616. Archived from the original on 1 November 2016.

- Tschopp, Jean-Marie; Rami-Porta, Ramon; Noppen, Marc; Astoul, Philippe (September 2006). "Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: state of the art". European Respiratory Journal. 28 (3): 637–50. doi:10.1183/09031936.06.00014206. PMID 16946095.

- Noppen, M.; De Keukeleire, T. (2008). "Pneumothorax". Respiration. 76 (2): 121–27. doi:10.1159/000135932. PMID 18708734.

- MacDuff, Andrew; Arnold, Anthony; Harvey, John; et al. (BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group) (December 2010). "Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society pleural disease guideline 2010". Thorax. 65 (8): ii18–ii31. doi:10.1136/thx.2010.136986. PMID 20696690.

- Leigh-Smith, S.; Harris, T. (January 2005). "Tension pneumothorax – time for a re-think?". Emergency Medicine Journal. 22 (1): 8–16. doi:10.1136/emj.2003.010421. PMC 1726546. PMID 15611534.

- de Menezes Lyra, Roberto (May–June 2016). "Etiology of primary spontaneous pneumothorax". Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia. 42 (3): 222–26. doi:10.1590/S1806-37562015000000230. PMC 5569604. PMID 27383937.

- Marx J (2010). Rosen's emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice (7th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier. pp. 393–96. ISBN 978-0-323-05472-0.

- Robinson, Paul D.; Cooper, Peter; Ranganathan, Sarath C. (September 2009). "Evidence-based management of paediatric primary spontaneous pneumothorax". Paediatric Respiratory Reviews. 10 (3): 110–17. doi:10.1016/j.prrv.2008.12.003. PMID 19651381.

- Chiu, Hsienchang Thomas; Garcia, Christine Kim (July 2006). "Familial spontaneous pneumothorax". Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 12 (4): 268–72. doi:10.1097/01.mcp.0000230630.73139.f0. PMID 16825879.

- Levine DJ, Sako EY, Peters J (2008). Fishman's Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 1520. ISBN 978-0-07-145739-2.

- Light RW (2007). Pleural diseases (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 307. ISBN 978-0-7817-6957-0.

- Nicholas Rathert, W. Scott Gilmore, MD, EMT-P (19 July 2013). "Treating Sucking Chest Wounds and Other Traumatic Chest Injuries". www.jems.com. Journal of Emergency Medical Services. Archived from the original on 8 April 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- Neuman TS (2003). "Arterial gas embolism and pulmonary barotrauma". In Brubakk AO, Neuman TS (eds.). Bennett and Elliott's physiology and medicine of diving (5th Rev ed.). United States: Saunders. pp. 558–61. ISBN 978-0-7020-2571-6.

- Grundy S, Bentley A, Tschopp JM (2012). "Primary spontaneous pneumothorax: a diffuse disease of the pleura". Respiration. 83 (3): 185–89. doi:10.1159/000335993. PMID 22343477.

- Seow, A; Kazerooni, E A; Pernicano, P G; Neary, M (1996). "Comparison of upright inspiratory and expiratory chest radiographs for detecting pneumothoraces". American Journal of Roentgenology. 166 (2): 313–16. doi:10.2214/ajr.166.2.8553937. ISSN 0361-803X. PMID 8553937.

- MacDuff, A.; Arnold, A.; Harvey, J. (2010). "Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society pleural disease guideline 2010". Thorax. 65 (Suppl 2): ii18–ii31. doi:10.1136/thx.2010.136986. ISSN 0040-6376. PMID 20696690.

- O'Connor, A R; Morgan, W E (2005). "Radiological review of pneumothorax". BMJ. 330 (7506): 1493–97. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7506.1493. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 558461. PMID 15976424.

- Baumann MH, Strange C, Heffner JE, Light R, Kirby TJ, Klein J, Luketich JD, Panacek EA, Sahn SA (February 2001). "Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: an American College of Chest Physicians Delphi consensus statement". Chest. 119 (2): 590–602. doi:10.1378/chest.119.2.590. PMID 11171742.

- Scalea TM, Rodriguez A, Chiu WC, Brenneman FD, Fallon WF, Kato K, McKenney MG, Nerlich ML, Ochsner MG, Yoshii H (1999). "Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (FAST): results from an international consensus conference". Journal of Trauma. 46 (3): 466–72. doi:10.1097/00005373-199903000-00022. PMID 10088853.

- Wilkerson RG, Stone MB (January 2010). "Sensitivity of bedside ultrasound and supine anteroposterior chest radiographs for the identification of pneumothorax after blunt trauma". Academic Emergency Medicine. 17 (1): 11–17. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00628.x. PMID 20078434.

- Volpicelli G (February 2011). "Sonographic diagnosis of pneumothorax". Intensive Care Medicine. 37 (2): 224–32. doi:10.1007/s00134-010-2079-y. PMID 21103861.

- Staub, LJ; Biscaro, RRM; Kaszubowski, E; Maurici, R (8 February 2018). "Chest ultrasonography for the emergency diagnosis of traumatic pneumothorax and haemothorax: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Injury. 49 (3): 457–466. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2018.01.033. PMID 29433802.

- "UOTW #6 – Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. 24 June 2014. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- "UOTW #62 – Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. 25 October 2015. Archived from the original on 9 May 2017.

- Keel M, Meier C (December 2007). "Chest injuries – what is new?". Current Opinion in Critical Care. 13 (6): 674–79. doi:10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282f1fe71. PMID 17975389.

- Lee C, Revell M, Porter K, Steyn R, Faculty of Pre-Hospital Care (March 2007). "The prehospital management of chest injuries: a consensus statement". Emergency Medicine Journal. 24 (3): 220–24. doi:10.1136/emj.2006.043687. PMC 2660039. PMID 17351237.

- Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, Kronick SL, Shuster M, Callaway CW, Kudenchuk PJ, Ornato JP, McNally B, Silvers SM, Passman RS, White RD, Hess EP, Tang W, Davis D, Sinz E, Morrison LJ (November 2010). "Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 122 (18 Suppl 3): S729–67. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970988. PMID 20956224.

- Ashby, M; Haug, G; Mulcahy, P; Ogden, KJ; Jensen, O; Walters, JA (18 December 2014). "Conservative versus interventional management for primary spontaneous pneumothorax in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD010565. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010565.pub2. PMC 6516953. PMID 25519778.

- Light RW (2007). Pleural diseases (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-7817-6957-0.

- Carson-Chahhoud, KV; Wakai, A; van Agteren, JE; Smith, BJ; McCabe, G; Brinn, MP; O'Sullivan, R (7 September 2017). "Simple aspiration versus intercostal tube drainage for primary spontaneous pneumothorax in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD004479. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004479.pub3. PMC 6483783. PMID 28881006.

- Chang, SH; Kang, YN; Chiu, HY; Chiu, YH (May 2018). "A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Comparing Pigtail Catheter and Chest Tube as the Initial Treatment for Pneumothorax". Chest. 153 (5): 1201–1212. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.048. PMID 29452099.

- Brims FJ, Maskell NA (2013). "Ambulatory treatment in the management of pneumothorax: a systematic review of the literature". Thorax. 68 (7): 664–69. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202875. PMID 23515437.

- Brown I, Palmer KT, Robin C (2007). Fitness for work: the medical aspects. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 481–82. ISBN 978-0-19-921565-2.

- Baumann MH, Noppen M (June 2004). "Pneumothorax". Respirology. 9 (2): 157–64. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1843.2004.00577.x. PMID 15182264.

- Levine DJ, Sako EY, Peters J (2008). Fishman's Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 1519. ISBN 978-0-07-145739-2.

- Light RW (2007). Pleural diseases (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-7817-6957-0.

- Bense L, Eklund G, Wiman LG (1987). "Smoking and the increased risk of contracting spontaneous pneumothorax". Chest. 92 (6): 1009–12. doi:10.1378/chest.92.6.1009. PMID 3677805.

- Light RW (2007). Pleural diseases (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-7817-6957-0.

- Sahn SA, Heffner JE (2000). "Spontaneous pneumothorax". New England Journal of Medicine. 342 (12): 868–74. doi:10.1056/NEJM200003233421207. PMID 10727592.

- Kaya SO, Karatepe M, Tok T, Onem G, Dursunoglu N, Goksin I (September 2009). "Were pneumothorax and its management known in 15th-century anatolia?". Texas Heart Institute Journal. 36 (2): 152–53. PMC 2676596. PMID 19436812.

- Laennec RTH (1819). Traité de l'auscultation médiate et des maladies des poumons et du coeur – part II (in French). Paris.

- Kjærgard H (1932). "Spontaneous pneumothorax in the apparently healthy". Acta Medica Scandinavica. 43 Suppl: 1–159. doi:10.1111/j.0954-6820.1932.tb05982.x.

- Tyson MD, Crandall WB (1941). "The surgical treatment of recurrent idiopathic spontaneous pneumothorax". Journal of Thoracic Surgery. 10: 566–70.

- Herzog H (1998). "History of tuberculosis". Respiration. 65 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1159/000029220. PMID 9523361.

- Stevenson, Angus (2010). Oxford Dictionary of English. OUP Oxford. p. 1369. ISBN 9780199571123. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016.

- Pawloski DR, Broaddus KD (2010). "Pneumothorax: a review". J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 46 (6): 385–97. doi:10.5326/0460385. PMID 21041331.

- "Causes of Respiratory Malfunction". Merck Veterinary Manual, 9th edition (online version). 2005. Archived from the original on 26 November 2010. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- "Equine trauma and first aid: wounds and lacerations". Merck Veterinary Manual, 9th edition (online version). 2005. Archived from the original on 6 September 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- "Primary survey and triage - breathing". Merck Veterinary Manual, 9th edition (online version). 2005. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |