Pneumoconiosis

Pneumoconiosis is the general term for a class of interstitial lung diseases where inhalation of dust has caused interstitial fibrosis. Pneumoconiosis often causes restrictive impairment,[1] although diagnosable pneumoconiosis can occur without measurable impairment of lung function. Depending on extent and severity, it may cause death within months or years, or it may never produce symptoms. It is usually an occupational lung disease, typically from years of dust exposure during work in mining; textile milling; shipbuilding, ship repairing, and/or shipbreaking; sandblasting; industrial tasks; rock drilling (subways or building pilings);[2] or agriculture.[3][4]

| Pneumoconiosis | |

|---|---|

| |

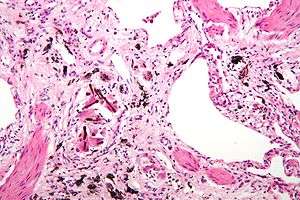

| Micrograph of asbestosis (with ferruginous bodies), a type of pneumoconiosis. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

In 2013, it resulted in 260,000 deaths globally, up from 251,000 deaths in 1990.[5] Of these deaths, 46,000 were due to silicosis, 24,000 due to asbestosis and 25,000 due to coal workers pneumoconiosis.[5]

Types

Depending upon the type of dust, the disease is given different names:

- Coalworker's pneumoconiosis (also known as miner's lung, black lung or anthracosis) – coal, carbon

- Aluminosis – Aluminium

- Asbestosis – asbestos

- Silicosis (also known as "grinder's disease" or Potter's rot, or when related to silica inhaled from the ash of an erupting volcano, pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis) – crystalline silica dust

- Bauxite fibrosis – bauxite

- Berylliosis – beryllium

- Siderosis – iron

- Byssinosis – cotton

- Silicosiderosis – mixed dust containing silica and iron

- Labrador lung (found in miners in Labrador, Canada) – mixed dust containing iron, silica and anthophyllite, a type of asbestos

- Stannosis – tin oxide

Pathogenesis

The reaction of the lung to mineral dusts depends on many variables, including size, shape, solubility, and reactivity of the particles. For example, particles greater than 5 to 10 μm are unlikely to reach distal airways, whereas particles smaller than 0.5 μm move into and out of alveoli, often without substantial deposition and injury. Particles that are 1 to 5 μm in diameter are the most dangerous, because they get lodged at the bifurcation of the distal airways. Coal dust is relatively inert, and large amounts must be deposited in the lungs before lung disease is clinically detectable. Silica, asbestos, and beryllium are more reactive than coal dust, resulting in fibrotic reactions at lower concentrations. Most inhaled dust is entrapped in the mucus blanket and rapidly removed from the lung by ciliary movement. However, some of the particles become impacted at alveolar duct bifurcations, where macrophages accumulate and engulf the trapped particulates. The pulmonary alveolar macrophage is a key cellular element in the initiation and perpetuation of lung injury and fibrosis. Many particles activate the inflammasome and induce IL-1 production. The more reactive particles trigger the macrophages to release a number of products that mediate an inflammatory response and initiate fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition. Some of the inhaled particles may reach the lymphatics either by direct drainage or within migrating macrophages and thereby initiate an immune response to components of the particulates and/or to self-proteins that are modified by the particles. This then leads to an amplification and extension of the local reaction. Tobacco smoking worsens the effects of all inhaled mineral dusts, more so with asbestos than with any other particle.[3]

Diagnosis

Positive indications on patient assessment:

- Shortness of breath

- Chest X-ray may show a characteristic patchy, subpleural, bibasilar interstitial infiltrates or small cystic radiolucencies called honeycombing.

Pneumoconiosis in combination with multiple pulmonary rheumatoid nodules in rheumatoid arthritis patients is known as Caplan's syndrome.[6]

Epidemiology

In 2013 pneumoconiosis resulted in 260,001 deaths up from 251,000 deaths in 1990.[5] Of these deaths 46,000 were due to silicosis, 24,000 due to asbestosis and 25,000 due to coal workers pneumoconiosis.[5]

Popular culture

- In the 1939 movie Four Wives, actor Eddie Albert plays a doctor studying pneumoconiosis.

- In the classic British film Brief Encounter (1945), derived from a Noël Coward play, housewife Laura (Celia Johnson) and physician Alec (Trevor Howard) begin an affair. She is desperately mesmerized in a train station lounge by his evocation of his passion for pneumoconiosis.

- In the 1995 British film Brassed Off, the band leader (Pete Postlethwaite) in a small coal-mining town is hospitalized with pneumoconiosis.

- A 2006 documentary film by Shane Roberts features interviews with miners suffering from the disease and footage shot inside the mine

- An episode of 1000 Ways to Die featured an incident where two kitchen workers succumb to pneumoconiosis from playing in cocoa powder.

- In the puzzle/shooter video game Portal 2, former CEO and founder of Aperture Science Laboratories, Cave Johnson, purportedly contracted and died of lunar pneumoconiosis after prolonged exposure to the moon rocks he was using in teleportation technology research.

- In the 2001 film Zoolander, the "black lung" is referenced to after the male model protagonist spends one day working in a coal mine.[7]

- In the 2004 BBC miniseries North & South, Bessy Higgins dies from pneumoconiosis from working in the cotton mill in 19th-century England.

- Pneumoconiosis was mentioned in the famous "Royal Episode" of Monty Python's Flying Circus in 1971.

See also

- Aluminosis

- Black Lung Benefits Act of 1973

- Chalicosis

- Philip D'Arcy Hart

- Popcorn workers' lung disease — diacetyl emissions and airborne dust from butter flavorings used in microwave popcorn production

References

- American Thoracic Society. "Diagnosis and Initial Management of Nonmalignant Diseases Related to Asbestos". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 170 (6): 691–715. doi:10.1164/rccm.200310-1436ST. PMID 15355871.

- Shih, Gerry (15 December 2019). "They built a Chinese boomtown. It left them dying of lung disease with nowhere to turn". New York Times. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- Kumar, MBBS, MD, FRCPath, Vinay (2013). Robbins Basic Pathology 9th Edition. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Elsevier Saunders. pp. 474–475. ISBN 978-1-4377-1781-5.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Schenker, Marc B.; Pinkerton, Kent E.; Mitchell, Diane; Vallyathan, Val; Elvine-Kreis, Brenda; Green, Francis H.Y. "Pneumoconiosis from Agricultural Dust Exposure among Young California Farmworkers". Environmental Health Perspectives. 117 (6): 988–994. doi:10.1289/ehp.0800144. PMC 2702418. PMID 19590695.

- GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385: 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- Andreoli, Thomas, ed. CECIL Essentials of Medicine. Saunders: Pennsylvania, 2004. p. 737.

- "Zoolander (2001)". IMDb.com.

Further reading

- Cochrane, A.L.; Blythe, M. (1989). One Man's Medicine, an autobiography of Professor Archie Cochrane. London: BMJ Books. ISBN 0727902776. (Paperback ed. (2009) Cardiff University ISBN 0954088433.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- "Pneumoconioses". NIOSH Safety and Health Topic. Center for Disease Control.

- "Black Lung Benefits Act". U.S. Department of Labor.

- Coal Workers' Pneumoconiosis at Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition

- Black Lung — United Mine Workers of America

- "Black Lung" (PDF). U.S. Department of Labor Mine Safety and Health Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-30.

- A Conversation about Mining and Black Lung Disease

- Flavorings-Related Lung Disease

- The Institute of Occupational Medicine and its research into pneumocomiosis

- Miller, B.G.; Kinnear, A.G. Pneumoconiosis in coalminers and exposure to dust of variable quartz content (PDF) (Technical report). Institute of Occupational Medicine. TM/88/17.