Photoheterotroph

Photoheterotrophs (Gk: photo = light, hetero = (an)other, troph = nourishment) are heterotrophic phototrophs—that is, they are organisms that use light for energy, but cannot use carbon dioxide as their sole carbon source. Consequently, they use organic compounds from the environment to satisfy their carbon requirements; these compounds include carbohydrates, fatty acids, and alcohols. Examples of photoheterotrophic organisms include purple non-sulfur bacteria, green non-sulfur bacteria, and heliobacteria.[1] Recent research has indicated that the oriental hornet and some aphids may be able to use light to supplement their energy supply.[2]

Metabolism

Photoheterotrophs generate ATP using light, in one of two ways:[3][4] they use a bacteriochlorophyll-based reaction center, or they use a bacteriorhodopsin. The chlorophyll-based mechanism is similar to that used in photosynthesis, where light excites the molecules in a reaction center and causes a flow of electrons through an electron transport chain (ETS). This flow of electrons through the proteins causes hydrogen ions to be pumped across a membrane. The energy stored in this proton gradient is used to drive ATP synthesis. Unlike in photoautotrophs, the electrons flow only in a cyclic pathway: electrons released from the reaction center flow through the ETS and return to the reaction center. They are not utilized to reduce any organic compounds. Purple non-sulfur bacteria, green non-sulfur bacteria and heliobacteria are examples of bacteria that carry out this scheme of photoheterotrophy.

Other organisms, including halobacteria and flavobacteria[5] and vibrios[6] have purple-rhodopsin-based proton pumps that supplement their energy supply. The archaeal version is called bacteriorhodopsin, while the eubacterial version is called proteorhodopsin. The pump consists of a single protein bound to a Vitamin A derivative, retinal. The pump may have accessory pigments (e.g., carotenoids) associated with the protein. When light is absorbed by the retinal molecule, the molecule isomerises. This drives the protein to change shape and pump a proton across the membrane. The hydrogen ion gradient can then be used to generate ATP, transport solutes across the membrane, or drive a flagellar motor. One particular flavobacterium cannot reduce carbon dioxide using light, but uses the energy from its rhodopsin system to fix carbon dioxide through anaplerotic fixation.[5] The flavobacterium is still a heterotroph as it needs reduced carbon compounds to live and cannot subsist on only light and CO2. It cannot carry out reactions in the form of

- n CO2 + 2n H2D + photons → (CH2O)n + 2n D + n H2O,

where H2D may be water, H2S or another compound/compounds providing the reducing electrons and protons; the 2D + H2O pair represents an oxidized form.

However, it can fix carbon in reactions like:

where malate or other useful molecules are otherwise obtained by breaking down other compounds by

- carbohydrate + O2 → malate + CO2 + energy.

This method of carbon fixation is useful when reduced carbon compounds are scarce and cannot be wasted as CO2 during interconversions, but energy is plentiful in the form of sunlight.

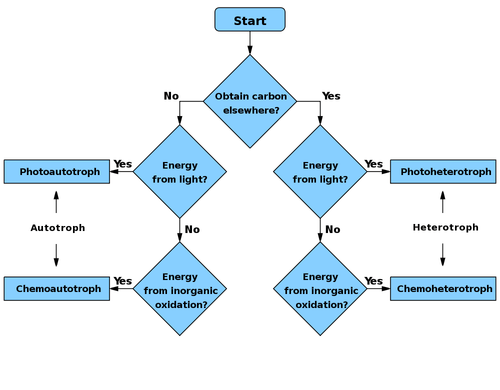

Flowchart

- Autotroph

- Chemoautotroph

- Photoautotroph

- Heterotroph

- Chemoheterotroph

- Photoheterotroph

See also

- Primary nutritional groups

References

- D.A. Bryant & N.-U. Frigaard (November 2006). "Prokaryotic photosynthesis and phototrophy illuminated". Trends Microbiol. 14 (11): 488–96. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2006.09.001. PMID 16997562.

- Valmalette, J. C.; Dombrovsky, A.; Brat, P.; Mertz, C.; Capovilla, M.; Robichon, A. (2012). "Light- induced electron transfer and ATP synthesis in a carotene synthesizing insect". Scientific Reports. 2: 579. doi:10.1038/srep00579. PMC 3420219. PMID 22900140.

- Bryant, Donald A.; Niels-Ulrik Frigaard (November 2006). "Prokaryotic photosynthesis and phototrophy illuminated". Trends in Microbiology. 14 (11): 488–496. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2006.09.001. ISSN 0966-842X. PMID 16997562.

- Zubkov, Mikhail V (2009-09-01). "Photoheterotrophy in Marine Prokaryotes". Journal of Plankton Research. 31 (9): 933–938. doi:10.1093/plankt/fbp043. ISSN 0142-7873. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- González, José M; Beatriz Fernández-Gómez; Antoni Fernàndez-Guerra; Laura Gómez-Consarnau; Olga Sánchez; Montserrat Coll-Lladó; Javier Del Campo; Lorena Escudero; Raquel Rodríguez-Martínez; Laura Alonso-Sáez; Mikel Latasa; Ian Paulsen; Olga Nedashkovskaya; Itziar Lekunberri; Jarone Pinhassi; Carlos Pedrós-Alió (2008-06-24). "Genome Analysis of the Proteorhodopsin-Containing Marine Bacterium Polaribacter Sp. MED152 (Flavobacteria)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (25): 8724–8729. doi:10.1073/pnas.0712027105. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2438413. PMID 18552178.

- Gómez-Consarnau, Laura; Neelam Akram; Kristoffer Lindell; Anders Pedersen; Richard Neutze; Debra L. Milton; José M. González; Jarone Pinhassi (2010). "Proteorhodopsin Phototrophy Promotes Survival of Marine Bacteria during Starvation". PLoS Biol. 8 (4): e1000358. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000358. PMC 2860489. PMID 20436956.