Pembrolizumab

Pembrolizumab (formerly lambrolizumab, trade name Keytruda)[1] is a humanized antibody used in cancer immunotherapy. This includes to treat melanoma, lung cancer, head and neck cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, and stomach cancer.[2] It is given by slow injection into a vein.[2]

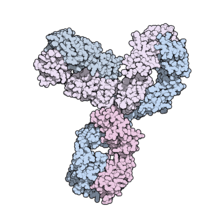

From PDB entry 5dk3 | |

| Monoclonal antibody | |

|---|---|

| Type | Whole antibody |

| Source | Humanized (from mouse) |

| Target | PD-1 |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Keytruda |

| Other names | MK-3475, lambrolizumab |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | IV |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem SID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.234.370 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C6534H10004N1716O2036S46 |

| Molar mass | 146–149 kDa g·mol−1 |

Common side effects include itchiness, rash, cough, fever, nausea, and constipation.[2] It is an IgG4 isotype antibody that blocks a protective mechanism of cancer cells and thereby, allows the immune system to destroy them. It targets the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) receptor of lymphocytes.

Pembrolizumab was approved for medical use in the United States in 2014.[2] In 2017 the FDA approved it for any unresectable or metastatic solid tumor with certain genetic anomalies (mismatch repair deficiency or microsatellite instability).[3]

Medical uses

As of 2019, pembrolizumab is used via intravenous infusion to treat inoperable or metastatic melanoma, metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in certain situations, as an first-line treatment for metastatic bladder cancer in patients who can’t receive cisplatin-based chemotherapy and have high levels of PD-L1, as a second-line treatment for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), after platinum-based chemotherapy, for the treatment of adult and pediatric patients with refractory classic Hodgkin's lymphoma (cHL), and recurrent locally advanced or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11]

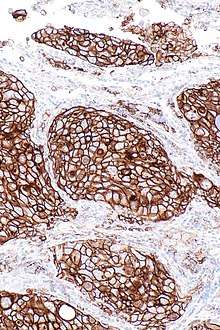

For NSCLC, pembrolizumab is a first-line treatment if the cancer overexpresses PD-L1, a PD-1 receptor ligand, and the cancer has no mutations in EGFR or in ALK; if chemotherapy has already been administered, then pembrolizumab can be used as a second-line treatment, but if the cancer has EGFR or ALK mutations, agents targeting those mutations should be used first.[4][12] Assessment of PD-L1 expression must be conducted with a validated and approved companion diagnostic.[4][9]

In 2017 the FDA approved pembrolizumab for any unresectable or metastatic solid tumor with certain genetic anomalies (mismatch repair deficiency or microsatellite instability).[3][13] This was the first time the FDA approved a cancer drug based on tumor genetics rather than tissue type or tumor site; therefore, pembrolizumab is a so-called tissue-agnostic drug.

Contraindications

If a person is taking corticosteroids or immunosuppressants, those drugs should be stopped before starting pembrolizumab because they may interfere with pembrolizumab; they may be used after pembrolizumab is started to deal with immune-related adverse effects.[5]

Women of child-bearing age should use contraception when taking pembrolizumab; it should not be administered to pregnant women because animal studies have shown that it can reduce tolerance to the fetus, increasing the risk of miscarriage. It is not known whether pembrolizumab is present in breast milk.[5]

As of 2017, the drug had not been tested in people with active infections (including any HIV, hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection), kidney or liver disease, active CNS metastases, active systemic autoimmune disease, interstitial lung disease, prior pneumonia, and people with a history of severe reaction to another monoclonal antibody.[5]

Adverse effects

People have had severe infusion-related reactions to pembrolizumab. There have also been severe immune-related adverse effects including lung inflammation (including fatal cases) and inflammation of endocrine organs that caused inflammation of the pituitary gland, of the thyroid (causing both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism in different people), and pancreatitis that caused Type 1 diabetes and diabetic ketoacidosis; some people have had to go on lifelong hormone therapy as a result (e.g. insulin therapy or thyroid hormones). People have also had colon inflammation, liver inflammation, kidney inflammation due to the drug.[5][14]

The common adverse reactions have been fatigue (24%), rash (19%), itchiness (pruritus) (17%), diarrhea (12%), nausea (11%) and joint pain (arthralgia) (10%).[5]

Other adverse effects occurring in between 1% and 10% of people taking pembrolizumab have included anemia, decreased appetite, headache, dizziness, distortion of the sense of taste, dry eye, high blood pressure, abdominal pain, constipation, dry mouth, severe skin reactions, vitiligo, various kinds of acne, dry skin, eczema, muscle pain, pain in a limb, arthritis, weakness, edema, fever, chills, myasthenia gravis, and flu-like symptoms.[5]

Mechanism of action

Pembrolizumab is a therapeutic antibody that binds to and blocks PD-1 located on lymphocytes. This receptor is generally responsible for preventing the immune system from attacking the body's own tissues; it is a so-called immune checkpoint.[15][16] Many cancers make proteins that bind to PD-1, thus shutting down the ability of the body to kill the cancer on its own.[9][15] Inhibiting PD-1 on the lymphocytes prevents this, allowing the immune system to target and destroy cancer cells;[17] this same mechanism also allows the immune system to attack the body itself, and checkpoint inhibitors like pembrolizumab have immune-dysfunction side effects as a result.[16]

Tumors that have mutations that cause impaired DNA mismatch repair, which often results in microsatellite instability, tend to generate many mutated proteins that could serve as tumor antigens; pembrolizumab appears to facilitate clearance of any such tumor by the immune system, by preventing the self-checkpoint system from blocking the clearance.[9][18]

Pharmacology

Since pembrolizumab is cleared from the circulation through non-specific catabolism, no metabolic drug interactions are expected and no studies were done on routes of elimination.[5] The systemic clearance [rate] is about 0.2 L/day and the terminal half-life is about 25 days.[5]

Chemistry and manufacturing

Pembrolizumab is an immunoglobulin G4, with a variable region against the human PD-1 receptor, a humanized mouse monoclonal [228-L-proline(H10-S>P)]γ4 heavy chain (134-218') disulfide and a humanized mouse monoclonal κ light chain dimer (226-226:229-229)-bisdisulfide.[19]

It is recombinantly manufactured in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells.[20]

History

Pembrolizumab was invented by scientists Gregory Carven, Hans van Eenennaam and John Dulos at Organon after which they worked with Medical Research Council Technology (now known as LifeArc) starting in 2006 to humanize the antibody; Schering-Plough acquired Organon in 2007 and Merck & Co. acquired Schering-Plough two years later.[21] Carven, van Eenennaam and Dulos were recognized as Inventors of the Year by the Intellectual Property Owners Education Foundation in 2016.[22]

The development program for pembrolizumab was seen as high priority at Organon, but low at Schering and later Merck. In early 2010 Merck terminated development and began preparing to out-license it.[23] Later in 2010 scientists from Bristol Myers Squibb published a paper in the New England Journal of Medicine showing that their checkpoint inhibitor, ipilimumab (Yervoy) had shown strong promise in treating metastatic melanoma and that a second Bristol-Myers Squibb checkpoint inhibitor, nivolumab, (Opdivo) was also promising.[23] Merck at that time had little commitment or expertise in either oncology or immunotherapy, but understood the opportunity and reacted strongly, reactivating the program and filing its IND by the end of 2010.[23] As one example, Martin Huber was one of the few senior people at Merck with strong experience in lung cancer drug development, but had been promoted to senior management and was no longer involved in product development. He stepped down from his role to lead clinical development of pembrolizumab for lung cancer.[23]

Scientists at the company argued for developing a companion diagnostic and limiting testing of the drug only to patients with biomarkers showing they were likely to respond, and received agreement from management. Some people, including shareholders and analysts, criticized this decision as it limited the potential market size for the drug, while others argued it increased the chances of proving the drug would work and would make clinical trials faster. (The trials would need fewer patients because of the likelihood of greater effect size.) Moving quickly and reducing the risk of failure was essential for catching up with Bristol-Myers Squibb, which had an approximate five year lead over Merck.[23] The phase I study started in early 2011, and Eric Rubin, who was running the melanoma trial, argued for and was able to win expansion of the trial until it reached around 1300 people. This was the largest Phase I study ever run in oncology, with the patients roughly divided between melanoma and lung cancer.[23]

In 2013 Merck quietly applied for and won a breakthrough therapy designation for the drug. This regulatory pathway was new at the time and not well understood. One of its advantages is that the FDA holds more frequent meetings with drug developers, reducing the risk of developers making mistakes or misunderstandings arising between regulators' expectations and what the developers want to do. This was Merck's first use of the designation and the reduction in regulatory risk was one of the reasons management was willing to put company resources into development.[23]

In 2013, the USAN name was changed from lambrolizumab to pembrolizumab.[19] In that year clinical trial results in advanced melanoma were published in the New England Journal of Medicine.[24] This was part of the large phase 1 NCT01295827 trial.[25]

On September 4, 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved pembrolizumab under the FDA Fast Track Development Program.[26] It is approved for use following treatment with ipilimumab, or after treatment with Ipilimumab and a BRAF inhibitor in advanced melanoma patients who carry a BRAF mutation.[27]

As of 2015, the only PD-1/PD-L1 targeting drugs on the market were pembrolizumab and Bristol-Myers Squibb's Opdivo, with clinical developments in the class of drugs receiving coverage in the New York Times.[28]

By April 2016, Merck applied for approval to market the drug in Japan and signed an agreement with Taiho Pharmaceutical to co-promote it there.[29]

In July 2015, pembrolizumab received marketing approval in Europe.[5][30]

On October 2, 2015, the FDA approved pembrolizumab for the treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in patients whose tumors express PD-L1 and who have failed treatment with other chemotherapeutic agents.[31]

In July 2016, the US FDA accepted for priority review an application for recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) after a platinum-based chemotherapy.[32] They granted accelerated approval to pembrolizumab as a treatment for patients with recurrent or metastatic (HNSCC) ("regardless of PD-L1 staining") following progression on a platinum-based chemotherapy, based on objective response rates (ORR) in the phase Ib KEYNOTE-012 study in August of the same year.[33] Full approval depended on the results of the phase III KEYNOTE-040 study (NCT02252042), which ran until Jan 2017.[33]

In May 2017, pembrolizumab received an accelerated approval from the FDA for use in any unresectable or metastatic solid tumor with DNA mismatch repair deficiencies or a microsatellite instability-high state (or, in the case of colon cancer, tumors that have progressed following chemotherapy). This approval marked the first instance in which the FDA approved marketing of a drug based only on the presence of a genetic mutation, with no limitation on the site of the cancer or the kind of tissue in which it originated.[13][18][34] The approval was based on a clinical trial of 149 patients with microsatellite instability-high or mismatch repair deficient cancers who enrolled on one of five single-arm trials. Ninety patients had colorectal cancer, and 59 patients had one of 14 other cancer types. The objective response rate for all patients was 39.6%. Response rates were similar across all cancer types, including 36% in colorectal cancer and 46% across the other tumor types. Notably, there were 11 complete responses, with the remainder partial responses. Responses lasted for at least six months in 78% of responders.[18] Because the clinical trial was fairly small, Merck is obligated to conduct further post-marketing studies to ensure that the results are valid.[35]

In June 2018, the FDA approved pembrolizumab for use in both advanced cervical cancer for PD-L1 positive patients[36] and for the treatment of adult and pediatric patients with refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL), or who have relapsed after two or more prior lines of therapy[37].

Society and culture

Pembrolizumab was priced at $150,000 per year when it launched (late 2014).[38]

Research

In 2015, Merck reported results in 13 cancer types; much attention was given to early results in head and neck cancer.[9][39][40]

As of May 2016, pembrolizumab was in Phase IB clinical trials for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), gastric cancer, urothelial cancer, and head and neck cancer (all under the "Keynote-012" trial) and in Phase II trial for TNBC (the "Keynote-086" trial).[41] At ASCO in June 2016, Merck reported that the clinical development program was directed to around 30 cancers and that it was running over 270 clinical trials (around 100 in combination with other treatments) and had four registration-enabling studies in process.[42]

Results of a Phase II clinical trial in Merkel-cell carcinoma were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in June 2016.[43]

Results of a clinical trial in people with untreatable metastases arising from various solid tumors were published in Science in 2017.[44]

It is in a phase III trial in combination with epacadostat, an Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1) inhibitor to treat melanoma.[9][45]

See also

References

![]()

- "Pembrolizumab". AdisInsight. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- "Pembrolizumab Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Syn, Nicholas L; Teng, Michele W L; Mok, Tony S K; Soo, Ross A (2017). "De-novo and acquired resistance to immune checkpoint targeting". The Lancet Oncology. 18 (12): e731–e741. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30607-1. PMID 29208439.

- "Pembrolizumab label" (PDF). FDA. May 2017. linked from Index page at FDA website November 2016

- "Pembrolizumab label at eMC". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. 27 January 2017.

- Redman, Jason M.; Gibney, Geoffrey T.; Atkins, Michael B. (6 February 2016). "Advances in immunotherapy for melanoma". BMC Medicine. 14 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/s12916-016-0571-0. PMC 4744430. PMID 26850630.

- Fuereder, Thorsten (20 June 2016). "Immunotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma". Memo - Magazine of European Medical Oncology. 9 (2): 66–69. doi:10.1007/s12254-016-0270-8. PMC 4923082. PMID 27429658.

- Pembrolizumab (KEYTRUDA) for classical Hodgkin lymphoma, 15 Mar 2017, FDA

- Syn, Nicholas L; Teng, Michele W L; Mok, Tony S K; Soo, Ross A (2017). "De-novo and acquired resistance to immune checkpoint targeting". The Lancet Oncology. 18 (12): e731–e741. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30607-1. PMID 29208439.

- Research, Center for Drug Evaluation and (2019-07-31). "FDA approves pembrolizumab for advanced esophageal squamous cell cancer". FDA.

- "Checkpoint Inhibitor Use Changed for Bladder Cancer". National Cancer Institute. 26 July 2018.

- Chen, Hongbin; Vachhani, Pankit (September 2016). "Spotlight on pembrolizumab in non-small cell lung cancer: the evidence to date". OncoTargets and Therapy. 9: 5855–5866. doi:10.2147/ott.s97746. PMC 5045223. PMID 27713639.

- "FDA grants accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for first tissue/site agnostic indication". Food and Drug Administration. May 23, 2017.

- Linardou, Helena; Gogas, Helen (July 2016). "Toxicity management of immunotherapy for patients with metastatic melanoma". Annals of Translational Medicine. 4 (14): 272. doi:10.21037/atm.2016.07.10. PMC 4971373. PMID 27563659.

- Francisco LM, Sage PT, Sharpe AH (Jul 2010). "The PD-1 pathway in tolerance and autoimmunity". Immunological Reviews. 236: 219–42. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00923.x. PMC 2919275. PMID 20636820.

- Buqué, Aitziber; et al. (2 March 2015). "Trial Watch: Immunomodulatory monoclonal antibodies for oncological indications". OncoImmunology. 4 (4): e1008814. doi:10.1080/2162402x.2015.1008814. PMC 4485728. PMID 26137403.

- Pardoll, DM (Mar 22, 2012). "The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy". Nature Reviews Cancer. 12 (4): 252–64. doi:10.1038/nrc3239. PMC 4856023. PMID 22437870.

- Bala, Sanjeeve; Nair, Abhi (30 May 2017). "Approved Drugs - FDA D.I.S.C.O.: First Tissue/Site Agnostic Approval Transcript". FDA.

- "Statement on a Nonproprietary Name Adopted by the USAN Council" (PDF). November 27, 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Assessment report: Keytruda. Procedure No. EMEA/H/C/003820/0000" (PDF). EMA. 21 May 2015.

- "Unlocking Checkpoint Inhibition". Translational Scientist. August 9, 2016.

- "Inventors of the Year". Inventors Digest. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- Shaywitz, David (July 26, 2017). "The Startling History Behind Merck's New Cancer Blockbuster". Forbes.

- Hamid, O; et al. (2013). "Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma". New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (2): 134–44. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1305133. PMC 4126516. PMID 23724846.

- Study of Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) in Participants With Progressive Locally Advanced or Metastatic Carcinoma, Melanoma, or Non-small Cell Lung Carcinoma (P07990/MK-3475-001/KEYNOTE-001) (KEYNOTE-001)

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (September 4, 2014). "FDA approves Keytruda for advanced melanoma". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- "FDA Approves Anti-PD-1 Drug for Advanced Melanoma". cancernetwork.com.

- Pollack, Andrew (May 29, 2015). "New Class of Drugs Shows More Promise in Treating Cancer". New York Times. Retrieved May 30, 2015.

- "Merck & Co and Taiho to co-promote cancer immunotherapy pembrolizumab in Japan". The Pharma Letter. April 13, 2016.

- "Keytruda index page at EMA". European Medicines Agency. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- "FDA approves Keytruda for advanced non-small cell lung cancer". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. October 2, 2015.

- Potential Biomarkers Identified for Pembrolizumab in Head and Neck Cancer. July 2016

- FDA Approves Pembrolizumab for Head and Neck Cancer. Aug 2016

- Ledford, Heidi (24 May 2017). "News: Tissue-independent cancer drug gets fast-track approval from US regulator". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22054.

- "Accelerated approval notice: BLA 125514/S-14" (PDF). FDA. 23 May 2017.

- "FDA Approves Pembrolizumab for Advanced Cervical Cancer with Disease Progression During or After Chemotherapy". ASCO. 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2018-06-13.

- Research, Center for Drug Evaluation and. "Approved Drugs - FDA approves pembrolizumab for treatment of relapsed or refractory PMBCL". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 2018-06-16.

- Amgen slaps record-breaking $178K price on rare leukemia drug Blincyto

- Timmerman, Luke (June 2, 2015). "ASCO Wrapup: Immunotherapy Shines, Hope For Brain Tumors, & The Great Cancer Drug Price Debate". Forbes.

- Adams, Katherine T. (24 July 2015). "Cancer Immunotherapies--and Their Cost--Take Center Stage at ASCO's 2015 Annual Meeting". Managed Care Magazine Online.

- Jenkins, Kristin (5 May 2016). "Keytruda Impresses in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer". MedPage Today.

- "Merck & Co updates Keytruda findings at ASCO". The Pharma Letter. June 10, 2016.

- Nghiem (2016). "PD-1 Blockade with Pembrolizumab in Advanced Merkel-Cell Carcinoma". N. Engl. J. Med. 374 (26): 2542–2552. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1603702. PMC 4927341. PMID 27093365.

- Le, DT; Durham, JN; Smith, KN; Wang, H; Bartlett, BR; Aulakh, LK; Lu, S; Kemberling, H; Wilt, C; Luber, BS; Wong, F; Azad, NS; Rucki, AA; Laheru, D; Donehower, R; Zaheer, A; Fisher, GA; Crocenzi, TS; Lee, JJ; Greten, TF; Duffy, AG; Ciombor, KK; Eyring, AD; Lam, BH; Joe, A; Kang, SP; Holdhoff, M; Danilova, L; Cope, L; Meyer, C; Zhou, S; Goldberg, RM; Armstrong, DK; Bever, KM; Fader, AN; Taube, J; Housseau, F; Spetzler, D; Xiao, N; Pardoll, DM; Papadopoulos, N; Kinzler, KW; Eshleman, JR; Vogelstein, B; Anders, RA; Diaz LA, Jr (8 June 2017). "Mismatch-repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade". Science. 357 (6349): 409–413. doi:10.1126/science.aan6733. PMC 5576142. PMID 28596308.

- A Phase 3 Study of Pembrolizumab + Epacadostat or Placebo in Subjects With Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma (Keynote-252 / ECHO-301)