Parechovirus B

Parechovirus B, formerly called the Ljungan virus, was first discovered in the mid-1990s after being isolated from a bank vole near the Ljungan river in Medelpad county, Sweden.[2] It has since been established that Parechovirus B, which is also found in several places in Europe and America, causes serious illness in wild as well as laboratory animals.[3][4][5][6] Several scientific articles have recently reported findings indicating that Parechovirus B is associated with malformations, intrauterine fetal death, and sudden infant death syndrome in humans.[7][8][9][10] In addition, studies are being conducted worldwide to investigate the possible connection of the virus to diabetes, neurological and other illnesses in humans.

| Parechovirus B | |

|---|---|

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Phylum: | incertae sedis |

| Order: | Picornavirales |

| Family: | Picornaviridae |

| Genus: | Parechovirus |

| Species: | Parechovirus B |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Parechovirus B belongs to the genus Parechovirus of the family Picornaviridae. Other members of this viral family include poliovirus, Hepatovirus A, and the viruses causing the common cold (rhinovirus).[11] One of the earliest scientific discoveries regarding Parechovirus B was that infected wild rodents developed diabetes if they were exposed to stress.[12] This has led to speculation that this disease may be the underlying cause of fluctuating rodent populations in Scandinavia; when rodents increase to high densities, they find it difficult to defend territory and obtain food, and then become more susceptible to predation. This stressful situation results in disease, death and population decline, leading to a pattern of cyclic variation in population size over time.[4]

Viral classification

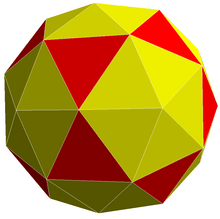

Parecherovirus B is a positive sense, single stranded RNA virus.[13] Parechovirus B is a virus that contains an outer shell. This outer shell, or capsid is made up of proteins set up in an icosahedral formation. Unlike other picornaviruses, the capsid shell of Parechovirus B has some proteins that protrude and are markedly displaced form the remainder fo the proteins. [14]

Genome replication

Cell entry

There is a receptor for Parechovirus B on the outer membrane of a cell called integrin αvβ6. The viral Protein RGD is what binds the virus to the cell it is trying to get into. The protein rests in the more flexible areas of the capsid shell. [15] Very little is known about how exactly the virus enters the cell. The virus can enter the cell through many different pathways, but most likely the integrin αvβ6 proteins on the host cell are still used.[16]

Replication

When the virus is replicating in cells, it typically uses the mechanisms already in the cell to replicate ins own genomic information. However, unlike many other picornaviruses, Pacherovirus B does not completely shut down the host cell's ability to replicate its own genomic information. Protein synthesis is maintained and not disrupted in the host cell. Maintaining protein synthesis allows the virus to prevent normal cellular replication, but still allow for ribosome dependent translation to still occur. The primary site for replication is also thought to be in the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts[13].

Associated diseases

Due to primary replication in the gastrointestinal tract, specifically the intestines, viral shedding can lead to many gastrointestinal issues. Diarrhea is one of the most common symptoms associated with being infected with picornaviruses, Pacherovirus B included. As for respiratory disease and symptoms, there is evidence that Pacherovirus B can cause respiratory disease. Wheezing and even contracting pneumonia have also been identified as symptoms of respiratory infection with Pacherovirus B[13].

References

- Knowles, Nick (7 July 2014). "Rename 12 picornavirus species" (PDF). International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Retrieved 1 May 2019.

Parechovirus Ljungan virus Parechovirus B Ljungan virus 1-4

- Niklasson, B.; Hörnfeldt, Birger; Hörling, Jan; et al. (1999). "A new picornavirus isolated from bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus)". Virology. 255 (1): 86–93. doi:10.1006/viro.1998.9557. PMID 10049824.

- Main, A.J.; R.E. Shope & R.C. Wallis (1976). "Characterization of Whitney's Clethrionomys gapperi virus isolates from Massachusetts". J Wildl Dis. 12 (2): 154–64. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-12.2.154. PMID 6801.

- Niklasson, B.; Feinstein, Ricardo E.; Samsioe, Annika; et al. (2006). "Diabetes and myocarditis in voles and lemmings at cyclic peak densities--induced by Ljungan virus?". Oecologia. 150 (1): 1–7. Bibcode:2006Oecol.150....1N. doi:10.1007/s00442-006-0493-1. PMID 16868760.

- Samsioe, A.; Saade, George; Sjöholm, Åke; et al. (2006). "Intrauterine death, fetal malformation, and delayed pregnancy in Ljungan virus-infected mice". Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 77 (4): 251–56. doi:10.1002/bdrb.20083. PMID 16894624.

- Salisbury, A. M.; Begon, M.; Dove, W.; Niklasson, B.; Stewart, J. P. (2013). "Ljungan virus is endemic in rodents in the UK". Archives of Virology. 159 (3): 547–51. doi:10.1007/s00705-013-1731-6. PMID 23665770.

- Niklasson, B.; Schønecker, Bryan; Bildsøe, Mogens; et al. (2003). "Development of type 1 diabetes in wild bank voles associated with islet autoantibodies and the novel ljungan virus". Int J Exp Diabesity Res. 4 (1): 35–44. doi:10.1080/15438600303733. PMC 2480497. PMID 12745669.

- Niklasson, B.; Papadogiannakis, Nikos; Gustafsson, Susanne; et al. (2009). "Zoonotic Ljungan virus associated with central nervous system malformations in terminated pregnancy". Birth Defects Res a Clin Mol Teratol. 85 (6): 542–55. doi:10.1002/bdra.20568. PMID 19180651.

- Niklasson, B.; Hörnfeldt, Birger; Klitz, William (2009). "Sudden infant death syndrome and Ljungan virus". Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 5 (4): 274–9. doi:10.1007/s12024-009-9086-8. PMID 19408134.

- Niklasson, B.; et al. (2007). "Association of zoonotic Ljungan virus with intrauterine fetal deaths". Birth Defects Res a Clin Mol Teratol. 79 (6): 488–93. doi:10.1002/bdra.20359. PMID 17335057.

- Joki-Korpela, P.; T. Hyypia (2001). "Parechoviruses, a novel group of human picornaviruses". Ann Med. 33 (7): 466–71. doi:10.3109/07853890109002095. PMID 11680794.

- Schoenecker, B.; K.E. Heller & T. Freimanis (2000). "Development of stereotypies and polydipsia in wild caught bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus) and their laboratory-bred offspring. Is polydipsia a symptom of diabetes mellitus?". Appl Anim Behav Sci. 68 (4): 349–357. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(00)00108-8. PMID 10844158.

- Harvala, H.; Simmonds, P. (2009). "Human parechoviruses: Biology, epidemiology and clinical significance". Journal of Clinical Virology. 45 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2009.03.009. ISSN 1386-6532.

- Zhu, Ling; Wang, Xiangxi; Ren, Jingshan; Porta, Claudine; Wenham, Hannah; Ekström, Jens-Ola; Panjwani, Anusha; Knowles, Nick J.; Kotecha, Abhay; Siebert, C. Alistair; Lindberg, A. Michael (2015-10-08). "Structure of Ljungan virus provides insight into genome packaging of this picornavirus". Nature Communications. 6 (1). doi:10.1038/ncomms9316. ISSN 2041-1723.

- Kalynych, Sergei; Pálková, Lenka; Plevka, Pavel (2015-11-18). "The Structure of Human Parechovirus 1 Reveals an Association of the RNA Genome with the Capsid". Journal of Virology. 90 (3): 1377–1386. doi:10.1128/jvi.02346-15. ISSN 0022-538X.

- Joki-Korpela, P.; Marjomaki, V.; Krogerus, C.; Heino, J.; Hyypia, T. (2001-02-15). "Entry of Human Parechovirus 1". Journal of Virology. 75 (4): 1958–1967. doi:10.1128/jvi.75.4.1958-1967.2001. ISSN 0022-538X.

External links

- Ljunganvirus.org – This site intends to be a knowledge bank summarizing the increasing mass of information generated regarding the effects of Parechovirus B infection. It is financed and written by Apodemus AB.

- "Developing tools and treatments for virus infections". – Apodemus is the research company that discovered Parechovirus B in the 1990s