Paranasal sinuses

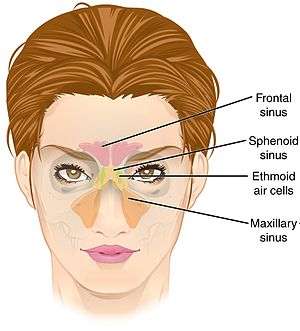

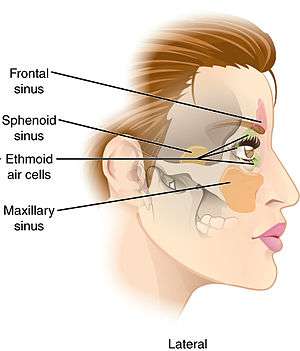

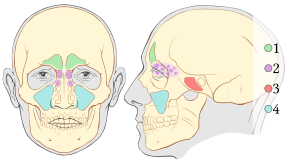

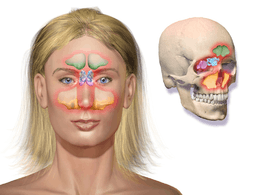

Paranasal sinuses are a group of four paired air-filled spaces that surround the nasal cavity.[1] The maxillary sinuses are located under the eyes; the frontal sinuses are above the eyes; the ethmoidal sinuses are between the eyes and the sphenoidal sinuses are behind the eyes. The sinuses are named for the facial bones in which they are located.

| Paranasal sinuses | |

|---|---|

Paranasal sinuses seen in a frontal view | |

Lateral projection of the paranasal sinuses | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | sinus paranasales |

| MeSH | D010256 |

| TA | A06.1.03.001 |

| FMA | 59679 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

Humans possess four paired paranasal sinuses, divided into subgroups that are named according to the bones within which the sinuses lie:

- The maxillary sinuses, the largest of the paranasal sinuses, are under the eyes, in the maxillary bones (open in the back of the semilunar hiatus of the nose). They are innervated by the trigeminal nerve (CN Vb).[2]

- The frontal sinuses, superior to the eyes, in the frontal bone, which forms the hard part of the forehead. They are also innervated by the trigeminal nerve (CN Va).[2]

- The ethmoidal sinuses, which are formed from several discrete air cells within the ethmoid bone between the nose and the eyes. They are innervated by the ethmoidal nerves, which branch from the nasociliary nerve of the trigeminal nerve (CN Va).

- The sphenoidal sinuses, in the sphenoid bone. They are innervated by the trigeminal nerve (CN Va & Vb).[2]

The paranasal air sinuses are lined with respiratory epithelium (ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium).

Development

Paranasal sinuses form developmentally through excavation of bone by air-filled sacs (pneumatic diverticula) from the nasal cavity. This process begins prenatally (intrauterine life), and it continues through the course of an organism's lifetime.

The results of experimental studies suggest that the natural ventilation rate of a sinus with a single sinus ostium (opening) is extremely slow. Such limited ventilation may be protective for the sinus, as it would help prevent drying of its mucosal surface and maintain a near-sterile environment with high carbon dioxide concentrations and minimal pathogen access. Thus composition of gas content in the maxillary sinus is similar to venous blood, with high carbon dioxide and lower oxygen levels compared to breathing air.[3]

At birth only the maxillary sinus and the ethmoid sinus are developed but not yet pneumatized; only by the age of seven they are fully aerated. The sphenoid sinus appears at the age of three, and the frontal sinuses first appear at the age of six, and fully develop during adulthood.[4]

Clinical significance

Inflammation

The paranasal sinuses are joined to the nasal cavity via small orifices called ostia. These become blocked easily by allergic inflammation, or by swelling in the nasal lining that occurs with a cold. If this happens, normal drainage of mucus within the sinuses is disrupted, and sinusitis may occur. Because the maxillary posterior teeth are close to the maxillary sinus, this can also cause clinical problems if any disease processes are present, such as an infection in any of these teeth. These clinical problems can include secondary sinusitis, the inflammation of the sinuses from another source such as an infection of the adjacent teeth.[5]

These conditions may be treated with drugs such as decongestants, which cause vasoconstriction in the sinuses; reducing inflammation; by traditional techniques of nasal irrigation; or by corticosteroid.

Cancer

Malignancies of the paranasal sinuses comprise approximately 0.2% of all malignancies. About 80% of these malignancies arise in the maxillary sinus. Men are much more often affected than women. They most often occur in the age group between 40 and 70 years. Carcinomas are more frequent than sarcomas. Metastases are rare. Tumours of the sphenoid and frontal sinuses are extremely rare.

History

Etymology

Sinus is a Latin word meaning a "fold", "curve", or "bay". Compare sine.

Other animals

Paranasal sinuses occur in many other animals, including most mammals, birds, non-avian dinosaurs, and crocodilians. The bones occupied by sinuses are quite variable in these other species.

Additional images

Paranasal sinuses radiograph (occipitofrontal)

Paranasal sinuses radiograph (occipitofrontal) Paranasal sinuses radiograph (occipitomental)

Paranasal sinuses radiograph (occipitomental) Paranasal sinuses radiograph (lateral)

Paranasal sinuses radiograph (lateral) Lateral projection of the paranasal sinuses as seen in an X-ray image

Lateral projection of the paranasal sinuses as seen in an X-ray image Paranasal sinuses

Paranasal sinuses Illustration depicting sinusitis

Illustration depicting sinusitis

See also

References

- "Paranasal sinuses".

- "Paranasal Sinus Anatomy: Overview, Gross Anatomy, Microscopic Anatomy". 2016-08-24. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "ARTICLES | Journal of Applied Physiology". jap.physiology.org. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- Towbin, Richard; Dunbar, J. Scott (1982). "The paranasal sinuses in childhood". RadioGraphics. 2 (2): 253–279. doi:10.1148/radiographics.2.2.253. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

- Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck, Fehrenbach and Herring, Elsevier, 2012, p. 68