Tyramine

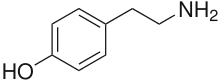

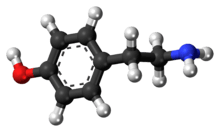

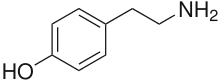

Tyramine (/ˈtaɪrəmiːn/ TY-rə-meen) (also spelled tyramin), also known under several other names,[note 1] is a naturally occurring trace amine derived from the amino acid tyrosine.[2] Tyramine acts as a catecholamine releasing agent. Notably, it is unable to cross the blood-brain barrier, resulting in only non-psychoactive peripheral sympathomimetic effects following ingestion. A hypertensive crisis can result, however, from ingestion of tyramine-rich foods in conjunction with the use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| ATC code |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | CYP2D6, FMO3, MAO-A, MAO-B, PNMT, DBH, others |

| Metabolites | 4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, dopamine, N-methyltyramine, octopamine |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.106 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C8H11NO |

| Molar mass | 137.179 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 164.5 °C (328.1 °F) [1] |

| Boiling point | 206 °C (403 °F) at 25 mmHg; 166 °C at 2 mmHg[1] |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Occurrence

Tyramine occurs widely in plants[3] and animals, and is metabolized by various enzymes, including monoamine oxidases. In foods, it often is produced by the decarboxylation of tyrosine during fermentation or decay. Foods containing considerable amounts of tyramine include:

- herring

- meats that are spoiled, pickled, aged, smoked, fermented, or marinated (some fish, poultry, and beef), and most pork (except cured ham)

- fermented dairy products such as sour cream, yogurt, and most cheeses (except ricotta, cottage, Monterey Jack, cream, and Neufchâtel cheeses)

- fermented plant foods such as alcoholic beverages, soy sauce, soybean condiments, teriyaki sauce, tempeh, miso soup, sauerkraut, and kimchi

- chocolate, shrimp paste, broad (fava) beans, green bean pods, Italian flat (Romano) beans, snow peas, edamame, avocados, bananas, raisins, dates, pineapple, eggplants, figs, red plums, raspberries, peanuts, Brazil nuts, coconuts, processed meat, yeast, an array of cacti, and the holiday plant mistletoe.

Physical effects and pharmacology

Evidence for the presence of tyramine in the human brain has been confirmed by postmortem analysis.[4] Additionally, the possibility that tyramine acts directly as a neuromodulator was revealed by the discovery of a G protein-coupled receptor with high affinity for tyramine, called TAAR1.[5][6] The TAAR1 receptor is found in the brain, as well as peripheral tissues, including the kidneys.[7] Tyramine binds to both TAAR1 and TAAR2 as an agonist in humans.[8]

Tyramine is physiologically metabolized by monoamine oxidases (primarily MAO-A), FMO3, PNMT, DBH, and CYP2D6.[9][10][11][12][13] Human monoamine oxidase enzymes metabolize tyramine into 4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde.[14] If monoamine metabolism is compromised by the use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and foods high in tyramine are ingested, a hypertensive crisis can result, as tyramine also can displace stored monoamines, such as dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine, from pre-synaptic vesicles.

The first signs of this effect were discovered by a British pharmacist who noticed that his wife, who at the time was on MAOI medication, had severe headaches when eating cheese.[15] For this reason, it is still called the "cheese effect" or "cheese crisis," though other foods can cause the same problem.[16]:30–31

Most processed cheeses do not contain enough tyramine to cause hypertensive effects, although some aged cheeses (such as Stilton) do.[17][18]

A large dietary intake of tyramine (or a dietary intake of tyramine while taking MAO inhibitors) can cause the tyramine pressor response, which is defined as an increase in systolic blood pressure of 30 mmHg or more. The increased release of norepinephrine (noradrenaline) from neuronal cytosol or storage vesicles is thought to cause the vasoconstriction and increased heart rate and blood pressure of the pressor response. In severe cases, adrenergic crisis can occur. Although the mechanism is unclear, tyramine ingestion also triggers migraine attacks in sensitive individuals. Vasodilation, dopamine, and circulatory factors are all implicated in the migraines. Double-blind trials suggest that the effects of tyramine on migraine may be adrenergic.[19]

Research reveals a possible link between migraines and elevated levels of tyramine. A 2007 review published in Neurological Sciences[20] presented data showing migraine and cluster diseases are characterized by an increase of circulating neurotransmitters and neuromodulators (including tyramine, octopamine and synephrine) in the hypothalamus, amygdala and dopaminergic system. People with Migraine are over-represented among those with inadequate natural monoamine oxidase, resulting in similar problems to individuals taking MAO inhibitors. Many migraine attack triggers are high in tyramine.[21]

If one has had repeated exposure to tyramine, however, there is a decreased pressor response; tyramine is degraded to octopamine, which is subsequently packaged in synaptic vesicles with norepinephrine (noradrenaline). Therefore, after repeated tyramine exposure, these vesicles contain an increased amount of octopamine and a relatively reduced amount of norepinephrine. When these vesicles are secreted upon tyramine ingestion, there is a decreased pressor response, as less norepinephrine is secreted into the synapse, and octopamine does not activate alpha or beta adrenergic receptors.

When using a MAO inhibitor (MAOI), an intake of approximately 10 to 25 mg of tyramine is required for a severe reaction, compared to 6 to 10 mg for a mild reaction.

Biosynthesis

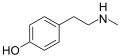

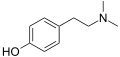

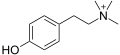

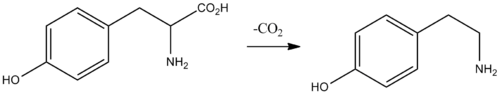

Biochemically, tyramine is produced by the decarboxylation of tyrosine via the action of the enzyme tyrosine decarboxylase.[22] Tyramine can, in turn, be converted to methylated alkaloid derivatives N-methyltyramine, N,N-dimethyltyramine (hordenine), and N,N,N-trimethyltyramine (candicine).

Tyramine

Tyramine N-Methyltyramine

N-Methyltyramine N,N-Dimethyltyramine (hordenine)

N,N-Dimethyltyramine (hordenine) N,N,N-Trimethyltyramine (candicine)

N,N,N-Trimethyltyramine (candicine)

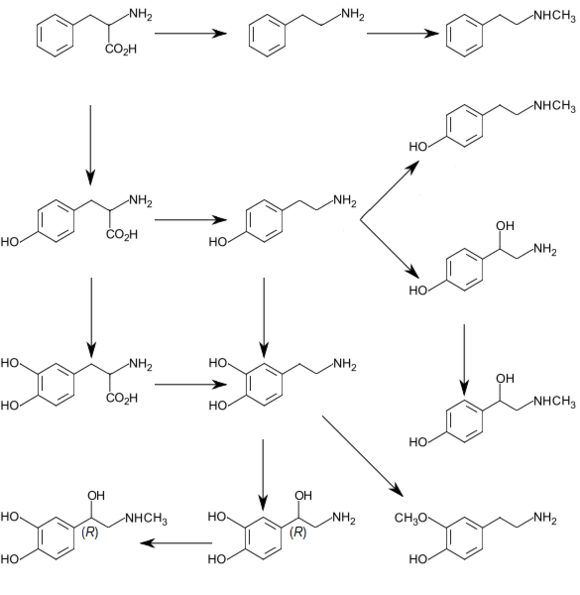

In humans, tyramine is produced from tyrosine, as shown in the following diagram.

Chemistry

In the laboratory, tyramine can be synthesized in various ways, in particular by the decarboxylation of tyrosine.[23][24][25]

Legal status

United States

Tyramine is not scheduled at the federal level in the United States and is therefore legal to buy, sell, or possess.[26]

Status in Florida

Tyramine is a Schedule I controlled substance, categorized as a hallucinogen, making it illegal to buy, sell, or possess in the state of Florida without a license at any purity level or any form whatsoever. The language in the Florida statute says tyramine is illegal in "any material, compound, mixture, or preparation that contains any quantity of [tyramine] or that contains any of [its] salts, isomers, including optical, positional, or geometric isomers, and salts of isomers, if the existence of such salts, isomers, and salts of isomers is possible within the specific chemical designation."[27]

This ban is likely the product of lawmakers overly eager to ban substituted phenethylamines, which tyramine is, in the mistaken belief that ring-substituted phenethylamines are hallucinogenic drugs like the 2C series of psychedelic substituted phenethylamines. The further banning of tyramine's optical isomers, positional isomers, or geometric isomers, and salts of isomers where they exist, means that meta-tyramine and phenylethanolamine, a substance found in every living human body, and other common, non-hallucinogenic substances are also illegal to buy, sell or possess in Florida. Given that tyramine occurs naturally in many foods and drinks (most commonly as a by-product of bacterial fermentation), e.g. wine, cheese, and chocolate, Florida's total ban on the substance may prove difficult to enforce.[28]

Notes

- Synonyms and alternative names include: 4-hydroxyphenethylamine, para-tyramine, mydrial, and uteramin; the latter two names are not commonly used. The IUPAC name is 4-(2-aminoethyl)phenol.

References

- The Merck Index, 10th Ed. (1983), p. 1405, Rahway: Merck & Co.

- "tyramine | C8H11NO". PubChem. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- T. A. Smith (1977) Phytochemistry 16 9–18.

- Philips, Rozdilsky Boulton (February 1978). "Evidence for the presence of m-tyramine, p-tyramine, tryptamine, and phenylethylamine in the rat brain and several areas of the human brain". Biological Psychiatry. 13 (1): 51–57. PMID 623853.

- Navarro, Gilmour Lewin (10 July 2006). "A Rapid Functional Assay for the Human Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1 Based on the Mobilization of Internal Calcium". J Biomol Screen. 11 (6): 668–693. doi:10.1177/1087057106289891. PMID 16831861.

- Liberles, Buck (10 August 2006). "A second class of chemosensory receptors in the olfactory epithelium". Nature. 442 (7103): 645–650. doi:10.1038/nature05066. PMID 16878137.

- Xie, Westmoreland Miller (May 2008). "Modulation of monoamine transporters by common biogenic amines via trace amine-associated receptor 1 and monoamine autoreceptors in human embryonic kidney 293 cells and brain synaptosomes". J. Pharm. 325 (2): 629–640. doi:10.1124/jpet.107.135079. PMID 18310473.

- Khan MZ, Nawaz W (October 2016). "The emerging roles of human trace amines and human trace amine-associated receptors (hTAARs) in central nervous system". Biomed. Pharmacother. 83: 439–449. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2016.07.002. PMID 27424325.

- "Trimethylamine monooxygenase (Homo sapiens)". BRENDA. Technische Universität Braunschweig. July 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Krueger SK, Williams DE (June 2005). "Mammalian flavin-containing monooxygenases: structure/function, genetic polymorphisms and role in drug metabolism". Pharmacol. Ther. 106 (3): 357–387. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.001. PMC 1828602. PMID 15922018.

Table 5: N-containing drugs and xenobiotics oxygenated by FMO - Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacol. Ther. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

- Lindemann L, Hoener MC (May 2005). "A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 26 (5): 274–281. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID 15860375.

- Wang X, Li J, Dong G, Yue J (February 2014). "The endogenous substrates of brain CYP2D". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 724: 211–218. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.12.025. PMID 24374199.

- "4-Hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde". Human Metabolome Database – Version 4.0. University of Alberta. 23 July 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- Sathyanarayana Rao TS, Vikram K. Yeragani VK (2009). "Hypertensive crisis and cheese". Indian J Psychiatry. 51 (1): 65–66. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.44910. PMC 2738414. PMID 19742203.

- E. Siobhan Mitchell "Antidepressants", chapter in Drugs, the Straight Facts, edited by David J. Triggle. 2004, Chelsea House Publishers

- Stahl SM, Felker A (2008). "Monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a modern guide to an unrequited class of antidepressants". CNS Spectrums. 13 (10): 855–870. doi:10.1017/S1092852900016965. PMID 18955941.

- Tyramine-restricted Diet 1998, W.B. Saunders Company.

- Ghose, K.; Coppen, A.; Carrol, D. (7 May 1977). "Intravenous tyramine response in migraine before and during treatment with indoramin". Br Med J. 1 (6070): 1191–1193. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.6070.1191. ISSN 0007-1447. PMC 1606859. PMID 324566.

- D'Andrea, G; Nordera, GP; Perini, F; Allais, G; Granella, F (May 2007). "Biochemistry of neuromodulation in primary headaches: focus on anomalies of tyrosine metabolism". Neurological Sciences. 28, Supplement 2 (S2): S94–S96. doi:10.1007/s10072-007-0758-4. PMID 17508188.

- "Headache Sufferer's Diet | National Headache Foundation". National Headache Foundation. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- Tyrosine metabolism - Reference pathway, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

- G. Barger (1909). "CXXVII.?Isolation and synthesis of p-hydroxyphenylethylamine, an active principle of ergot soluble in water". J. Chem. Soc. 95: 1123–1128. doi:10.1039/ct9099501123.

- Waser, Ernst (1925). "Untersuchungen in der Phenylalanin-Reihe VI. Decarboxylierung des Tyrosins und des Leucins". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 8: 758–773. doi:10.1002/hlca.192500801106.

- Buck, Johannes S. (1933). "Reduction of Hydroxymandelonitriles. A New Synthesis of Tyramine". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 55 (8): 3388–3390. doi:10.1021/ja01335a058.

- §1308.11 Schedule I

- "Statutes & Constitution :View Statutes : Online Sunshine". leg.state.fl.us. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- Suzzi, Giovanna; Torriani, Sandra (18 May 2015). "Editorial: Biogenic amines in foods". Frontiers in Microbiology. 6: 472. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.00472. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 4435245. PMID 26042107.