Outpatient commitment

Outpatient commitment—also called Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT) or a Community Treatment Order (CTO)—refers to a civil court procedure wherein a judge orders an individual diagnosed with a severe mental disorder who is experiencing a psychiatric crisis that requires intervention to adhere to an outpatient treatment plan designed to prevent further deterioration that is harmful to themselves or others.

This form of involuntary treatment is distinct from involuntary commitment in that the individual subject to the court order continues to live in their home community rather than being detained in hospital or incarcerated. The individual may be subject to rapid recall to hospital, including medication over objection, if the conditions of the order are broken, and the person's mental health deteriorates. This generally means taking psychiatric medication as directed and may also include attending appointments with a mental health professional, and sometimes even not to take non-prescribed illicit drugs and not associate with certain people or in certain places deemed to have been linked to a deterioration in mental health in that individual.

Criteria for outpatient commitment are established by law, which vary among nations and, in the U.S. and Canada, among states or provinces. Some jurisdictions require court hearings and others require that treating psychiatrists comply with a set of requirements before compulsory treatment is instituted. When a court process is not required, there is usually a form of appeal to the courts or appeal to or scrutiny by tribunals set up for that purpose. Community treatment laws have generally followed the worldwide trend of community treatment. See mental health law for details of countries which do not have laws that regulate compulsory treatment.

Terminology

In the United States the term "assisted outpatient treatment" (AOT) is often used and refers to a process whereby a judge orders a qualifying person with symptoms of severe untreated mental illness to adhere to a mental health treatment plan while living in the community. The plan typically includes medication and may include other forms of treatment as well.[1] Patients are often monitored and assigned to case managers or a community dedicated to treating mental health known as assertive community treatment (ACT).[2]

Australia, Canada, England, and New Zealand use the term "community treatment order" (CTO).[3][4][5]

Involuntary Treatment and International Human Rights Law

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, General comment No. 1 (2014) on Article 12: Equal recognition before the law, specifies that forced treatment, among other discriminatory practices must be abolished in order to ensure that full legal capacity is restored to persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others. [6]

Implementation

Discussions of "outpatient commitment" began in the psychiatry community in the 1980s following deinstitutionalization, a trend that led to the widespread closure of public psychiatric hospitals and resulted in the discharge of large numbers of people with mental illness to the community.

Europe

Denmark

Denmark introduced outpatient commitment in 2010 with the Mental Health Act (Danish: Lov om anvendelse af tvang i psykiatrien).[7]

Germany

In Germany, as of 2014, only former forensic psychiatry patients may be placed under community treatment orders.[8] Legislation to allow for wider use of CTOs was considered in 2003–2004, but it was ultimately rejected by the Bundestag.[8]

The Netherlands

As of 2014, Dutch law provides for community treatment orders, and an individual who does not comply with the terms of their CTO may be subject to immediate involuntary commitment.[8]

Norway

When Norway introduced outpatient commitment in the 1961 Mental Health Act, it could only be mandated for to individuals who had previously been admitted for inpatient treatment.[7] Revisions in 1999 and 2006 provided for outpatient commitment without previous inpatient treatment, but this provision is seldom used.[7]

Sweden

In Sweden, the Compulsory Psychiatric Care Act (Swedish: Lag om psykiatrisk tvångsvård) provides for an administrative court to mandate psychiatric treatment to prevent harm to the individual or others.[9]:61 The law was created in 1991 and revised in 2008.[9]:62

United Kingdom

In England the Mental Health Act 2007 introduced "community treatment orders (CTOs)".[5]

North America

In the last decade of the 20th century and the first of the 21st, "outpatient commitment" laws were passed in a number of U.S. states and jurisdictions in Canada.

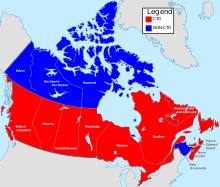

Canada

In the mid-1990s, Saskatchewan became the first Canadian province to implement community treatment orders, and Ontario followed in 2000.[4] As of January 2016, New Brunswick was the only province without legislation that provided for either CTOs or extended leave.[4]

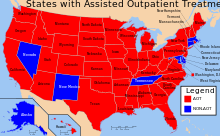

United States

By the end of 2010, 44 U.S. states had enacted some version of an outpatient commitment law. In some cases, passage of the laws followed widely publicized tragedies, such as the murders of Laura Wilcox and Kendra Webdale.

Oceania

Australia and New Zealand introduced community treatment orders in the 1980s and 1990s.[3]

Australia

In Australia, community treatment orders last for a maximum of twelve months but can be renewed after review by a tribunal.

Evidence

There have not been very many clinical trials performed evaluating outpatient commitment. Weak evidence suggests that compulsory community or involuntary outpatient treatment for people who have severe mental illness does not result in an improvement in use of the service, social functioning, or an improvement in quality of life, when compared to people who participated in voluntary treatments or short sessions of conditional leave.[10]

Research published in 2013 showed that Kendra's Law in New York, which served about 2,500 patients at a cost of $32 million, had positive results in terms of net cost, reduced hospitalization, reduced arrests, use of outpatient treatment and use of medication.[11] About $125 million is also spent annually on improved outpatient treatment for patients who are not subject to the law. In contrast to New York, despite wide adoption of outpatient commitment, the programs were generally not adequately funded.[12]

“Although numerous AOT programs currently operate across the United States, it is clear that the intervention is vastly underutilized."[13]

Arrests, danger, and violence

The National Institute of Justice consideres assisted outpatient treatment an effective crime prevention program.[14]

“For those who received AOT, the odds of any arrest were 2.66 times greater (p<.01) and the odds of arrest for a violent offense 8.61 times greater (p<.05) before AOT than they were in the period during and shortly after AOT. The group never receiving AOT had nearly double the odds (1.91, p<.05) of arrest compared with the AOT group in the period during and shortly after assignment.”[15]

“The odds of arrest for participants currently receiving AOT were nearly two-thirds lower (OR=.39, p<.01) than for individuals who had not yet initiated AOT or signed a voluntary service agreement.”[16]

Kendra's Law has lowered risk of violent behaviors, reduced thoughts about suicide, and enhanced capacity to function despite problems with mental illness. Patients given mandatory outpatient treatment—who were more violent to begin with—were nevertheless four times less likely than members of the control group to perpetrate serious violence after undergoing treatment. Patients who underwent mandatory treatment reported higher social functioning and slightly less stigma, rebutting claims that mandatory outpatient care is a threat to self-esteem.[17]

55% fewer recipients engaged in suicide attempts or physical harm to self. 47% fewer physically harmed others. 46% fewer damaged or destroyed property. 43% fewer threatened physical harm to others. Overall, the average decrease in harmful behaviors was 44%.

“Subjects who were ordered to outpatient commitment were less likely to be criminally victimized than those who were released without outpatient commitment.”[18]

Outcomes and hospital admissions

AOT “programs improve adherence with outpatient treatment and have been shown to lead to significantly fewer emergency commitments, hospital admissions, and hospital days as well as a reduction in arrests and violent behavior.”[19]

“The likelihood of psychiatric hospital admission was significantly reduced by approximately 25% during the initial six-month court order…and by over one-third during a subsequent six-month renewal of the order…. Similar significant reductions in days of hospitalization were evident during initial court orders and subsequent renewals…. Improvements were also evident in receipt of psychotropic medications and intensive case management services. Analysis of data from case manager reports showed similar reductions in hospital admissions and improved engagement in services.”[20]

74% fewer participants experienced homelessness. 77% fewer experienced psychiatric hospitalization. 56% reduction in length of hospitalization. 83% fewer experienced arrest. 87% fewer experienced incarceration. 49% fewer abused alcohol. 48% fewer abused drugs. Consumer participation and medication compliance improved. The number of individuals exhibiting good adherence to meds increased 51%. The number of individuals exhibiting good service engagement increased 103%. Consumer perceptions were positive. 75% reported that AOT helped them gain control over their lives. 81% said AOT helped them get and stay well. 90% said AOT made them more likely to keep appointments and take meds. 87% of participants said they were confident in their case manager's ability. 88% said they and their case manager agreed on what was important to work on.

In Nevada County, CA, AOT (“Laura's Law”) decreased the number of psychiatric hospital days 46.7%, the number of incarceration days 65.1%, the number of homeless days 61.9%, and the number of emergency interventions 44.1%. Laura's Law implementation saved $1.81–$2.52 for every dollar spent, and receiving services under Laura's Law caused a “reduction in actual hospital costs of $213,300” and a “reduction in actual incarceration costs of $75,600.”[21]

In New Jersey, Kim Veith, director of clinical services at Ocean Mental Health Services, noted the AOT pilot program performed “beyond wildest dreams.” AOT reduced hospitalizations, shortened inpatient stays, reduced crime and incarceration, stabilized housing, and reduced homelessness. Of clients who were homeless, 20% are now in supportive housing, 40% are in boarding homes, and 20% are living successfully with family members.[22]

Writing in the British Journal of Psychiatry in 2013, Jorun Rugkåsa and John Dawson stated, "The current evidence from RCTs suggests that CTOs do not reduce readmission rates over 12 months."[23]

“We find that New York State’s AOT Program improves a range of important outcomes for its recipients, apparently without feared negative consequences to recipients.”

“The increased services available under AOT clearly improve recipient outcomes, however, the AOT court order, itself, and its monitoring do appear to offer additional benefits in improving outcomes.”

Effect on mental illness system

Access to services

AOT has been instrumental in increasing accountability at all system levels regarding delivery of services to high need individuals. Community awareness of AOT has resulted in increased outreach to individuals who had previously presented engagement challenges to mental health service providers.” “Improved treatment plan development, discharge planning, and coordination of service planning. Processes and structures developed for AOT have resulted in improvements to treatment plans that more appropriately match the needs of individuals who have had difficulties using mental health services in the past.” “Improved collaboration between mental health and court systems. As AOT processes have matured, professionals from the two systems have improved their working relationships, resulting in greater efficiencies, and ultimately, the conservation of judicial, clinical, and administrative resources. There is now an organized process to prioritize and monitor individuals with the greatest need; AOT ensures greater access to services for individuals whom providers have previously been reluctant to serve; There is now increased collaboration between inpatient and community-based providers.”[24]

In New York City net costs declined 50% in the first year after assisted outpatient treatment began and an additional 13% in the second year. In non-NYC counties, costs declined 62% in the first year and an additional 27% in the second year. This was in spite of the fact that psychotropic drug costs increased during the first year after initiation of assisted outpatient treatment, by 40% and 44% in the city and five-county samples, respectively. The increased community-based mental health costs were more than offset by the reduction in inpatient and incarceration costs. Cost declines associated with assisted outpatient treatment were about twice as large as those seen for voluntary services.[11]

“In all three regions, for all three groups, the predicted probability of an MPR ≥80% improved over time (AOT improved by 31–40 percentage points, followed by enhanced services, which improved by 15–22 points, and ‘neither treatment,’ improving 8–19 points). Some regional differences in MPR trajectories were observed.”[25]

“In tandem with New York's AOT program, enhanced services increased among involuntary recipients, whereas no corresponding increase was initially seen for voluntary recipients. In the long run, however, overall service capacity was increased, and the focus on enhanced services for AOT participants appears to have led to greater access to enhanced services for both voluntary and involuntary recipients.”[26]

“It is also important to recognize that the AOT order exerts a critical effect on service providers stimulating their efforts to prioritize care for AOT recipients.”

Race

“We find no evidence that the AOT Program is disproportionately selecting African Americans for court orders, nor is there evidence of a disproportionate effect on other minority populations. Our interviews with key stakeholders across the state corroborate these findings.”

“We found no evidence of racial bias. Defining the target population as public-system clients with multiple hospitalizations, the rate of application to white and black clients approaches parity.”[27]

Service engagement

“After 12 months or more on AOT, service engagement increased such that AOT recipients were judged to be more engaged than voluntary patients. This suggests that after 12 months or more, when combined with intensive services, AOT increases service engagement compared to voluntary treatment alone.” Consumers Approve. Despite being under a court order to participate in treatment, current AOT recipients feel neither more positive nor more negative about their treatment experiences than comparable individuals who are not under AOT.”[20]

“When the court order was for seven months or more, improved medication possession rates and reduced hospitalization outcomes were sustained even when the former AOT recipients were no longer receiving intensive case coordination services.”[21]

In Los Angeles, CA, the AOT pilot program reduced incarceration 78%, hospitalization 86%, hospitalization after discharge from the program 77%, and cut taxpayer costs 40%.[28]

In North Carolina, AOT reduced the percentage of persons refusing medications to 30%, compared to 66% of patients not under AOT.[29]

In Ohio, AOT increased attendance at outpatient psychiatric appointments from 5.7 to 13.0 per year. It increased attendance at day treatment sessions from 23 to 60 per year. “During the first 12 months of outpatient commitment, patients experienced significant reductions in visits to the psychiatric emergency service, hospital admissions, and lengths of stay compared with the 12 months before commitment.”[30]

In Arizona, “71% [of AOT patients] … voluntarily maintained treatment contacts six months after their orders expired” compared with “almost no patients” who were not court-ordered to outpatient treatment.[31]

In Iowa, “it appears as though outpatient commitment promotes treatment compliance in about 80% of patients… After commitment is terminated, about ¾ of that group remain in treatment on a voluntary basis.”[32]

Controversy

Proponents have argued that outpatient commitment improves mental health, increases the effectiveness of treatment, lowers incidence of homelessness, arrest, incarceration and hospitalization and reduces costs. Opponents of outpatient commitment laws argue that they unnecessarily limit freedom, force people to ingest dangerous medications, or are applied with racial and socioeconomic biases.

Proponents

While many outpatient commitment laws have been passed in response to violent acts committed by people with mental illness, most proponents involved in the outpatient commitment debate base their arguments on the quality of life and cost associated with untreated mental illness and "revolving door patients" who experience a cycle of hospitalization, treatment and stabilization, release, and decompensation. While the cost of repeated hospitalzations is indisputable, quality-of-life arguments rest on an understanding of mental illness as an undesirable and dangerous state of being. Outpatient commitment proponents point to studies performed in North Carolina and New York that have found some positive impact of court-ordered outpatient treatment. Proponents include: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), U.S. Department of Justice, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), U. S Department of Health and Human Services, American Psychiatric Association, National Alliance on Mental Illness, International Association of Chiefs of Police. SAMHSA included Assisted Outpatient Treatment in their National Registry of Evidence Based Program and Practices.[13] Crime Solutions:[14] Management Strategies to Reduce Psychiatric Readmissions[33]

Opponents

Outpatient commitment opponents make several varied arguments. Some dispute the positive effects of compulsory treatment, questioning the methodology of studies that show effectiveness. Others highlight negative effects of treatment. Still others point to disparities in the way these laws are applied.

The opponents claim they are giving medication to the patient, but there are no brain chemical imbalances to correct in "mental illness".[34] Our ability to control ourselves and reason comes from the mind, and the brain is being reduced in size from the psychiatric medications.[35][36][37][38]

The slippery slope argument of "If government bodies are given power, they will use it in excess." was proven when 350-450 CTO's were expected to be issued in 2008 and more than five times that number were issued in the first few months. Every year there are increasing numbers of people subject to CTO's.[39][40][41]

The psychiatric survivors movement opposes compulsory treatment on the basis that the ordered drugs often have serious or unpleasant side-effects such as tardive dyskinesia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, excessive weight gain leading to diabetes, addiction, sexual side effects, and increased risk of suicide. The New York Civil Liberties Union has denounced what they see as racial and socioeconomic biases in the issuing of outpatient commitment orders.[42][43] The main opponents to any kind of coercion, including the outpatient commitment and any other form of involuntary commitment, are Giorgio Antonucci and Thomas Szasz.

See also

US specific:

General:

- Involuntary treatment

- Deinstitutionalisation

- Deinstitutionalisation in Italy

- Psychiatric reform in Italy

- Giorgio Antonucci

References

- Org, M. I. P. "AOT (Assisted Outpatient Treatment) Guide". Mental Illness Policy Org. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- Org, M. I. P. "AOT (Assisted Outpatient Treatment) Guide". Mental Illness Policy Org. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- Rugkåsa, Jorun (January 2016). "Effectiveness of Community Treatment Orders: The International Evidence". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 61 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1177/0706743715620415. PMC 4756604. PMID 27582449.

- Kisely, Steve (January 2016). "Canadian Studies on the Effectiveness of Community Treatment Orders". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 61 (1): 7–14. doi:10.1177/0706743715620414. PMC 4756603. PMID 27582448.

- Supervised Community Treatment, Mind, retrieved 2011-08-28

- "Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Eleventh session 31 March–11 April 2014 General comment No. 1 (2014) Article 12: Equal recognition before the law".

- Riley, Henriette; Straume, Bjørn; Høyer, Georg (2 May 2017). "Patients on outpatient commitment orders in Northern Norway". BMC Psychiatry. 17 (1): 157. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1331-1. PMC 5414164. PMID 28464805.

- Steinert, Tilman; Noorthoorn, Eric O.; Mulder, Cornelis L. (24 September 2014). "The use of coercive interventions in mental health care in Germany and the Netherlands. A comparison of the developments in two neighboring countries". Frontiers in Public Health. 2: 141. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2014.00141. PMC 4173217. PMID 25309893.

- Reitan, Therese (March–April 2016). "Commitment without confinement: Outpatient compulsory care for substance abuse, and severe mental disorder in Sweden". International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 45: 60–69. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2016.02.011. PMID 26912456.

- Kisely, Steve R.; Campbell, Leslie A.; O'Reilly, Richard (2017). "Compulsory community and involuntary outpatient treatment for people with severe mental disorders". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD004408. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004408.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 4393705. PMID 28303578.

- Swanson, Jeffrey W.; Van Dorn, Richard A.; Swartz, Marvin S.; et al. (July 30, 2013). "The Cost of Assisted Outpatient Treatment: Can It Save States Money?". American Journal of Psychiatry. 170 (12): 1423–1432. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12091152. PMID 23896998. Archived from the original on August 8, 2013. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

Assisted outpatient treatment requires a substantial investment of state resources but can reduce overall service costs for persons with serious mental illness.

- Belluck, Pam (July 30, 2013). "Program Compelling Outpatient Treatment for Mental Illness Is Working, Study Says". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- Stettin, Brian (February 2015). "Intervention Summary: Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT)". NREPP: SAMHSA'S National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices. Archived from the original on 1 February 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- "Program Profile: Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT)". CrimeSolutions.gov. National Institute of Justice. March 26, 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- Link, Bruce G.; Epperson, Matthew W.; Perron, Brian E.; et al. (2011). "Arrest Outcomes Associated With Outpatient Commitment in New York State". Psychiatric Services. 62 (5): 504–8. doi:10.1176/ps.62.5.pss6205_0504. PMC 5826718. PMID 21532076.

- Gilbert, Allison R.; Moser, Lorna L.; Van Dorn, Richard A.; et al. (2010). "Reductions in Arrest Under Assisted Outpatient Treatment in New York". Psychiatric Services. 61 (10): 996–9. doi:10.1176/ps.2010.61.10.996. PMID 20889637.

- Phelan, Jo C.; Sinkewicz, Marilyn; Castille, Dorothy M.; et al. (2010). "Effectiveness and Outcomes of Assisted Outpatient Treatment in New York State". Psychiatric Services. 61 (2): 137–43. doi:10.1176/ps.2010.61.2.137. PMID 20123818.

- Hiday, Virginia Aldigé; Swartz, Marvin S.; Swanson, Jeffrey W.; et al. (2002). "Impact of Outpatient Commitment on Victimization of People With Severe Mental Illness". American Journal of Psychiatry. 159 (8): 1403–11. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1403. PMID 12153835.

- "Extensive New Independent Support for Assisted Outpatient Treatment from AHRQ Report". Mental Illness Policy Org. 17 November 2016.

- Swartz, Marvin S.; Wilder, Christine M.; Swanson, Jeffrey W.; et al. (October 2010). "Assessing Outcomes for Consumers in New York's Assisted Outpatient Treatment Program". Psychiatric Services. 61 (10): 976–81. doi:10.1176/ps.2010.61.10.976. PMID 20889634.

- Van Dorn, Richard A.; Swanson, Jeffrey W.; Swartz, Marvin S.; et al. (October 2010). "Continuing Medication and Hospitalization Outcomes After Assisted Outpatient Treatment in New York". Psychiatric Services. 61 (10): 982–7. doi:10.1176/ps.2010.61.10.982. PMID 20889635.

- "Success of AOT in New Jersey 'Beyond Wildest Dreams'". Treatment Advocacy Center. September 2, 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- Rugkåsa, Jorun; Dawson, John (December 2013). "Community treatment orders: current evidence and the implications". British Journal of Psychiatry. 203 (6): 406–8. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.113.133900. PMID 24297787.

- New York State Office of Mental Health (2005). Kendra's Law: Final Report on the Status of Assisted Outpatient Treatment (PDF) (Report to Legislature). Albany: New York State. p. 60. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- Busch, Alisa B.; Wilder, Christine M.; Van Dorn, Richard A.; et al. (2010). "Changes in Guideline-Recommended Medication Possession After Implementing Kendra's Law in New York". Psychiatric Services. 61 (10): 1000–5. doi:10.1176/ps.2010.61.10.1000. PMC 6690587. PMID 20889638.

- Swanson, Jeffrey W.; Van Dorn, Richard A.; Swartz, Marvin S.; et al. (2010). "Robbing Peter to Pay Paul: Did New York State's Outpatient Commitment Program Crowd Out Voluntary Service Recipients?". Psychiatric Services. 61 (10): 988–95. doi:10.1176/ps.2010.61.10.988. PMID 20889636.

- Swanson, Jeffrey; Swartz, Marvin; Van Dorn, Richard A.; et al. (2009). "Racial Disparities In Involuntary Outpatient Commitment: Are They Real?". Health Affairs. 28 (3): 816–26. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.816. PMID 19414892.

- Southard, Marvin (February 24, 2011). Assisted Outpatient Treatment Program Outcomes Report (PDF) (Report). Los Angeles, CA: Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Hiday, Virginia Aldigé; Scheid-Cook, Teresa L. (1987). "The North Carolina experience with outpatient commitment: A critical appraisal". International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 10 (3): 215–32. doi:10.1016/0160-2527(87)90026-4. PMID 3692660.

- Munetz, M.R.; Grande, T.; Kleist, J.; et al. (November 1996). "The effectiveness of outpatient civil commitment". Psychiatric Services. 47 (11): 1251–3. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.454.5055. doi:10.1176/ps.47.11.1251. PMID 8916245.

- Van Putten RA, Santiago JM, Berren MR (September 1988). "Involuntary outpatient commitment in Arizona: a retrospective study". Hospital & Community Psychiatry. 39 (9): 953–8. doi:10.1176/ps.39.9.953. PMID 3215643.

- Rohland, Barbara (1998). The role of outpatient commitment in the management of persons with schizophrenia (PDF) (Report). Iowa Consortium for Mental Health Services, Training and Research. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- Gaynes, Bradley N.; Brown, Carrie; Lux, Linda J.; et al. (May 2015). Management Strategies to Reduce Psychiatric Readmissions (Technical Brief). Effective Health Care Program. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. PMID 26020093. 15-EHC018-EF.

- Pies, Ronald W. (July 11, 2011). "Psychiatry's New Brain-Mind and the Legend of the Chemical Imbalance". Psychiatric Times.

- Ho, Beng-Choon; Andreasen, Nancy C.; Ziebell, Steven; et al. (2011). "Long-term Antipsychotic Treatment and Brain Volumes". Archives of General Psychiatry. 68 (2): 128–37. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.199. PMC 3476840. PMID 21300943.

- Dorph-Petersen, Karl-Anton; Pierri, Joseph N.; Perel, James M.; et al. (2005). "The Influence of Chronic Exposure to Antipsychotic Medications on Brain Size before and after Tissue Fixation: A Comparison of Haloperidol and Olanzapine in Macaque Monkeys". Neuropsychopharmacology. 30 (9): 1649–61. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300710. PMID 15756305.

- Radua, J.; Borgwardt, S.; Crescini, A.; et al. (2012). "Multimodal meta-analysis of structural and functional brain changes in first episode psychosis and the effects of antipsychotic medication". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 36 (10): 2325–33. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.07.012. PMID 22910680.

- Harrow, Martin; Jobe, Thomas H. (2007). "Factors involved in outcome and recovery in schizophrenia patients not on antipsychotic medications: a 15-year multifollow-up study". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 195 (5): 406–14. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000253783.32338.6e (inactive 2019-12-11). PMID 17502806.

- McLaughlin, Ken (October 7, 2014). "Community Treatment Orders: Politics and psychiatry in a culture of fear". Politics.co.uk.

- "Inpatients Formally Detained in Hospitals Under the Mental Health Act 1983 and Patients Subject to Supervised Community Treatment, England - 2014-2015, Annual figures" (Press release). NHS Digital. October 23, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- "Number of Mental Health detentions and Community Treatment Order rises" (Press release). NHS Digital. October 23, 2012. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- "Implementation of 'Kendra's Law' is Severely Biased" (PDF). New York Lawyers for the Public Interest. April 7, 2005.

- "Testimony On Extending Kendra's Law". NYCLU. Archived from the original on 2006-01-09. Retrieved 2006-04-02.