Olestra

Olestra (also known by its brand name Olean) is a fat substitute that adds no calories to products. It has been used in the preparation of otherwise high-fat foods such as potato chips, thereby lowering or eliminating their fat content. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) originally approved olestra for use as a replacement for fats and oils in prepackaged ready-to-eat snacks in 1996,[1] concluding that such use "meets the safety standard for food additives, reasonable certainty of no harm".[2] In the late 1990s, Olestra lost its popularity due to side effects, but products containing the ingredient can still be purchased at grocery stores in some countries.

| |

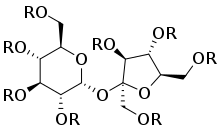

Top: Generic 2D structure of olestra where R = H or fatty acid group, C(O)CnHm Bottom: Stereoscopic animation of a representative olestra molecule with 8 unsaturated fatty acid groups | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Olean |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C n+12H 2n+22O 13 (Where fatty acids are saturated) |

| Molar mass | Variable |

| | |

Commercialization

Olestra was discovered accidentally by Procter & Gamble (P&G) researchers F. Mattson and R. Volpenhein in 1968 while researching fats that could be more easily digested by premature infants.[3] In 1971, P&G met with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to examine what sort of testing would be required to introduce olestra as a food additive.[4]

During the following tests, P&G noticed a decline in blood cholesterol levels as a side effect of olestra replacing natural dietary fats. Following this potentially lucrative possibility, in 1975, P&G filed a new request with the FDA to use olestra as a "drug", specifically to lower cholesterol levels.[4] The lengthy series of studies that followed failed, however, to demonstrate the 15% reduction required by the FDA to be approved as a treatment. Further work on olestra languished.

In 1984, the FDA allowed Kellogg to claim publicly that their high-fiber breakfast cereals were effective in reducing the risk of cancer. P&G immediately started another test series that lasted three years. When these tests were completed, P&G filed for approval as a food additive for up to 35% replacement of fats in home cooking and 75% in commercial uses.[4]

One of the main concerns the FDA had about olestra was it might encourage consumers to eat more of the "top of the pyramid" foods because of the perception of its being healthier. This could result in consumers engaging in over-consumption, thinking the addition of olestra would remove negative consequences.[5] In light of this possibility, approving it as an additive would have meant consumers would be consuming a food with a relatively high amount of an additive, whose long-term health effects were not documented. This made the FDA particularly hesitant to approve the product, as well as the side effects, such as diarrhea, and concern for the loss of fat-soluble vitamins.[3] In August 1990, P&G narrowed their focus to "savory snacks", potato chips, tortilla chips, crackers and similar foods.

By this point, the original patents were approaching their 1995 expiration. P&G lobbied for an extension, which they received in December 1993. This extension lasted until 25 January 1996.[6] With pressure from P&G, the approval was finally granted on 24 January, one day before the patent expired, automatically extending the patent two years.[6]

At the time of the 1996 ruling, FDA concluded that, "to avoid being misbranded…olestra-containing foods would need to bear a label statement to inform consumers about possible effects of olestra on the gastrointestinal system. The label statement also would clarify that the added vitamins were present to compensate for any nutritional effects of olestra, rather than to provide enhanced nutritional value".[7] The FDA later removed the label saying that the "current label does not accurately communicate information to consumers".[8] The FDA also agreed with P&G that the "label statement could be misleading and cause consumers of olestra to attribute serious problems to olestra when this was unlikely to be the case".[9]

Olestra was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use as a food additive in 1996, and was initially used in potato chips under the WOW brand by Frito Lay. In 1998, the first year olestra products were marketed nationally after the FDA's Food Advisory Committee confirmed a judgment it made two years earlier, sales were over $400 million.[10] By 2000, though, sales slowed to $200 million. P&G abandoned attempts to widen the uses of olestra, and sold off its Cincinnati-based factory to Twin Rivers Technologies in February 2002.[6]

As of 2013, the Lay's Light chips were still available, listing olestra as an ingredient.[11] Pringles Light potato crisps, manufactured by Kellogg's (though at one time a P&G product), use Olean brand olestra.

Side effects

Starting in 1996, an FDA-mandated health warning label read "This Product Contains Olestra. Olestra may cause abdominal cramping and loose stools (anal leakage). Olestra inhibits the absorption of some vitamins and other nutrients. Vitamins A, D, E, and K have been added".[12]

These symptoms, normally occurring only by excessive consumption in a short period of time, are known as steatorrhea, and caused by an excess of fat in stool.

The FDA removed the warning requirement in 2003, as it had "conducted a scientific review of several post-market studies submitted by P&G, as well as adverse event reports submitted by P&G and the Center for Science in the Public Interest. The FDA concluded the label statement was no longer warranted".[13] The FDA also agreed with P&G that the "label statement could be misleading and cause consumers of olestra to attribute serious problems to olestra when this [was] unlikely to be the case".[9]

When removing the olestra warning label, the FDA cited a six-week P&G study of more than 3000 people showing the olestra-eating group experienced only a small increase in bowel movement frequency compared to the control group.[11] The FDA concluded that "subjects eating olestra-containing chips were no more likely to report having had loose stools, abdominal cramps, or any other GI symptom compared to subjects eating an equivalent amount of [potato] chips".[14]

In addition to the effects of the health warnings on public acceptance of the product, olestra might not have lived up to consumer expectations of speedy results. If consumers believed they could eat more to compensate for the fat calories "saved", olestra would not be an effective way to improve overall diet.[15] The manufacturers claim that the authentic taste and feel of olestra offsets this tendency,[16] and some studies have shown that people who consume foods with olestra don’t eat more to offset the loss in calories.[17] P&G conducted publicity campaigns to highlight olestra's benefits, including working directly with the health-care community.[18]

Olestra is prohibited from sale in many markets, including the European Union and Canada.[19][20]

Consumption of olestra may encourage rats to eat too much of foods containing regular fats, due to the learning of an incorrect association between fat intake and calories. Rats that were fed regular potato chips as well as chips cooked with olestra gained more weight when subsequently eating a high-fat diet than rats that received just regular chips.[21]

Chemistry

Triglycerides, the energy-yielding dietary fats, consist of three fatty acids bonded in the form of esters to a glycerol backbone. Olestra uses sucrose as the backbone in place of glycerol, and it can form esters with up to eight fatty acids.[22] Olestra is a mixture of hexa-, hepta-, and octa-esters of sucrose with various long chain fatty acids. The resulting radial arrangement is too large and irregular to move through the intestinal wall and be absorbed into the bloodstream. Olestra has the same taste and mouthfeel as fat, but it passes through the gastrointestinal tract undigested without contributing calories or nutritive value to the diet.

From a mechanical point of view, scientists were able to manipulate the compound in such a way that it could be used in place of cooking oils in the preparation of many types of food.[3]

Since it contains fatty acid functional groups, olestra is able to dissolve lipid-soluble vitamins, such as vitamin D, vitamin E, vitamin K, and vitamin A, along with carotenoids. Fat-soluble nutrients consumed with olestra products are excreted with the undigested olestra molecules. To counteract this loss of nutrients, products made with olestra are fortified with oil-soluble vitamins.[23]

Applications

P&G is marketing its sucrose ester products under the brand "Sefose" for use as an industrial lubricant and paint additive.[24] Because olestra is made by chemically combining sugar and vegetable oil, it releases no toxic fumes and could potentially become a safe and environmentally friendly replacement for petrochemicals in these applications.[25] It is currently used as a base for deck stains and a lubricant for small power tools, and there are plans to use it on larger machinery.[26]

In 1999, researchers discovered olestra helps facilitate the removal of toxins from the brain, as it apparently binds to dioxins in a manner similar to that of normal fats. This unexpected side effect may make the substance useful in treating victims of dioxin poisoning.[27][28]

In 2005, research by groups at University of Cincinnati School of Medicine in Ohio and the University of Western Australia indicates olestra can be used to treat poisoning due to exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), including chloracne symptoms.[29] In 2014, Ronald Jandacek Ph.D. and collaborators showed that olestra supplied in the diet reduced body burden of PCBs in a pilot study on a cohort in Anniston AL that had been exposed to these toxins.[30]

Notes

- FDA Regulations (at 172.867)

- FDA Docket; p. 46399.

- Nestle, p. 340

- Nestle, p. 341

- Nestle, pp. 339–40

- "A Brief History of Olestra" Archived 2003-12-12 at the Wayback Machine, CSPI

- FDA Docket; p. 46364.

- FDA Docket; p. 46387.

- FDA Docket; p. 46397.

- Nestle, p. 338

- "Nutrition Facts Label" Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- "FDA approves fat substitute, Olestra", retrieved December 6, 2006

- "FDA Changes Labeling Requirement for Olestra". Retrieved October 12, 2007

- FDA Docket; p 46372.

- Nestle, p. 353

- "Olean Brand Olestra: Frequently Asked Questions". Retrieved 2012-04-16.

- Bray, G., Sparti, A., et al. “Effect of Two Weeks Fat Replacement by Olestra on Food Intake and Energy Metabolism” FASEB J 1995; 9:A439 (abstr).

- Nestle, p. 351

- Peale, Cliff (June 23, 2000). "Canadian ban adds to woes for P&G's olestra". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- "Everything you wanted to know about Olestra". Healthy and Hot. 2007-08-23. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- Swithers, S.E., Ogden, S.B., & Davidson, T.L. (June 20, 2011). “Fat Substitutes Promote Weight Gain in Rats Consuming High-Fat Diets”. Behavioral Neuroscience. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/a0024404 .

- Food and Chemistry Archived 2011-05-26 at the Wayback Machine, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 1993, p. 29. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- "The Problems With Olestra" Archived 2007-07-02 at the Wayback Machine, Center for Science in the Public Interest

- "Sefose". P&G Chemicals. Retrieved 2012-08-28.

- Ballantyne, Coco (6 Apr 2009). "Olestra makes a comeback – This time in paints and lubricants, not potato chips". 60-Second Science. Scientific American. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- Ballantyne, Coco (13 Apr 2009). "New chemicals for eco-friendly paints and lubricants". 60-Second Science. Scientific American. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- Severe 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) Intoxication: Clinical and Laboratory Effects Archived 2009-01-18 at the Wayback Machine retrieved December 6, 2006

- "Olestra Could Be Antidote to Toxins", University of Columbus Health News, 2005.

- Redgrave TG, Wallace P, Jandacek RJ, Tso P (2005). "Treatment with a dietary fat substitute decreased Arochlor 1254 contamination in an obese diabetic male". J. Nutr. Biochem. 16 (6): 383–84. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.12.014. PMID 15936651.

- Jandacek, Ronald J.; Heubi, James E.; Buckley, Donna D.; Khoury, Jane C.; Turner, Wayman E.; Sjödin, Andreas; Olson, James R.; Shelton, Christie; Helms, Kim (April 2014). "Reduction of the body burden of PCBs and DDE by dietary intervention in a randomized trial". The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 25 (4): 483–88. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2014.01.002. ISSN 1873-4847. PMC 3960503. PMID 24629911.

References

- Nestle, Marion. Food Politics. University of California Press, Ltd.: London, 2002.