Vestibulo–ocular reflex

The vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) is a reflex, where activation of the vestibular system of the inner ear causes eye movement. This reflex functions to stabilize images on the retinas (when gaze is held steady on a location) during head movement by producing eye movements in the direction opposite to head movement, thus preserving the image on the center of the visual field(s). For example, when the head moves to the right, the eyes move to the left, and vice versa. Since slight head movement is present all the time, VOR is necessary for stabilizing vision: patients whose VOR is impaired find it difficult to read using print, because they cannot stabilize the eyes during small head tremors, and also because damage to the VOR can cause vestibular nystagmus.[1]

The VOR does not depend on visual input. It can be elicited by caloric (hot or cold) stimulation of the inner ear, and works even in total darkness or when the eyes are closed. However, in the presence of light, the fixation reflex is also added to the movement.[2]

In other animals, the organs that coordinate balance and motor coordination do not operate independently from the organs that control the eyes. A fish, for instance, moves its eyes by reflex when its tail is moved. Humans have semicircular canals, neck muscle "stretch" receptors, and the utricle (gravity organ). Though the semicircular canals cause most of the reflexes which are responsive to acceleration, the maintaining of balance is mediated by the stretch of neck muscles and the pull of gravity on the utricle (otolith organ) of the inner ear.[2]

The VOR has both rotational and translational aspects. When the head rotates about any axis (horizontal, vertical, or torsional) distant visual images are stabilized by rotating the eyes about the same axis, but in the opposite direction.[3] When the head translates, for example during walking, the visual fixation point is maintained by rotating gaze direction in the opposite direction[4], by an amount that depends on distance.[5]

Circuit

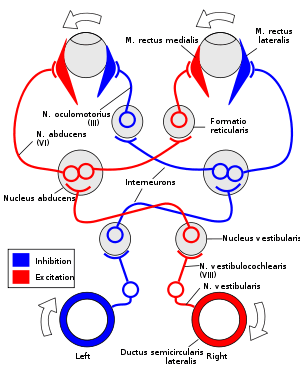

The VOR is ultimately driven by signals from the vestibular apparatus in the inner ear. The semicircular canals detect head rotation and drive the rotational VOR, whereas the otoliths detect head translation and drive the translational VOR. The main "direct path" neural circuit for the horizontal rotational VOR is fairly simple. It starts in the vestibular system, where semicircular canals get activated by head rotation and send their impulses via the vestibular nerve (cranial nerve VIII) through the vestibular ganglion and end in the vestibular nuclei in the brainstem. From these nuclei, fibers cross to the contralateral cranial nerve VI nucleus (abducens nucleus). There they synapse with 2 additional pathways. One pathway projects directly to the lateral rectus of the eye via the abducens nerve. Another nerve tract projects from the abducens nucleus by the medial longitudinal fasciculus to the contralateral oculomotor nucleus, which contains motorneurons that drive eye muscle activity, specifically activating the medial rectus muscle of the eye through the oculomotor nerve (cranial nerve III).

Another pathway (not in picture) directly projects from the vestibular nucleus through the ascending tract of Dieters to the ipsilateral medial rectus motoneuron. In addition there are inhibitory vestibular pathways to the ipsilateral abducens nucleus. However no direct vestibular neuron to medial rectus motoneuron pathway exists.[6]

Similar pathways exist for the vertical and torsional components of the VOR.

In addition to these direct pathways, which drive the velocity of eye rotation, there is an indirect pathway that builds up the position signal needed to prevent the eye from rolling back to center when the head stops moving. This pathway is particularly important when the head is moving slowly because here position signals dominate over velocity signals. David A. Robinson discovered that the eye muscles require this dual velocity-position drive, and also proposed that it must arise in the brain by mathematically integrating the velocity signal and then sending the resulting position signal to the motoneurons. Robinson was correct: the 'neural integrator' for horizontal eye position was found in the nucleus prepositus hypoglossi[7] in the medulla, and the neural integrator for vertical and torsional eye positions was found in the interstitial nucleus of Cajal[8] in the midbrain. The same neural integrators also generate eye position for other conjugate eye movements such as saccades and smooth pursuit.

Excitatory example

For instance, if the head is turned clockwise as seen from above, then excitatory impulses are sent from the semicircular canal on the right side via the vestibular nerve (cranial nerve VIII) through Scarpa's ganglion and end in the right vestibular nuclei in the brainstem. From this nuclei excitatory fibres cross to the left abducens nucleus. There they project and stimulate the lateral rectus of the left eye via the abducens nerve. In addition, by the medial longitudinal fasciculus and oculomotor nuclei, they activate the medial rectus muscles on the right eye. As a result, both eyes will turn counter-clockwise.

Furthermore, some neurons from the right vestibular nucleus directly stimulate the right medial rectus motoneurons, and inhibits the right abducens nucleus.

Speed

The vestibulo-ocular reflex needs to be fast: for clear vision, head movement must be compensated almost immediately; otherwise, vision corresponds to a photograph taken with a shaky hand. To achieve clear vision, signals from the semicircular canals are sent as directly as possible to the eye muscles: the connection involves only three neurons, and is correspondingly called the three neuron arc. Using these direct connections, eye movements lag the head movements by less than 10 ms,[9] and thus the vestibulo-ocular reflex is one of the fastest reflexes in the human body.

VOR suppression

During head-free pursuit of moving targets, the VOR is counterproductive to the goal of reducing retinal offset. Research indicates that there exists mechanisms to suppress VOR using active visual feedback.[10] In the absence of visual feedback, such as during occlusions, we use anticipatory (extra-retinal) signals to supplement our pursuit movements by VOR suppression.[11]

Gain

The "gain" of the VOR is defined as the change in the eye angle divided by the change in the head angle during the head turn. Ideally the gain of the rotational VOR is 1.0. The gain of the horizontal and vertical VOR is usually close to 1.0, but the gain of the torsional VOR (rotation around the line of sight) is generally low.[3] The gain of the translational VOR has to be adjusted for distance, because of the geometry of motion parallax. When the head translates, the angular direction of near targets changes faster than the angular direction of far targets.[5]

If the gain of the VOR is wrong (different from 1)—for example, if eye muscles are weak, or if a person puts on a new pair of eyeglasses—then head movement results in image motion on the retina, resulting in blurred vision. Under such conditions, motor learning adjusts the gain of the VOR to produce more accurate eye motion. This is what is referred to as VOR adaptation.

Ethanol consumption can disrupt the VOR, reducing dynamic visual acuity.[12]

Testing

This reflex can be tested by the rapid head impulse test or Halmagyi–Curthoys test, in which the head is rapidly moved to the side with force, and is controlled if the eyes succeed to remain to look in the same direction. When the function of the right balance system is reduced, by a disease or by an accident, a quick head movement to the right cannot be sensed properly anymore. As a consequence, no compensatory eye movement is generated, and the patient cannot fixate a point in space during this rapid head movement.

The head impulse test can be done at the bed side and used as a screening tool for problems with a person's vestibular system.[13] It can also be diagnostically tested by doing a video-head impose test (VHIT). In this diagnostic test, a person wears highly sensitive goggles that detect rapid changes in eye movement. This test can provide site-specific information on vestibular system and its function.[14]

Another way of testing the VOR response is a caloric reflex test, which is an attempt to induce nystagmus (compensatory eye movement in the absence of head motion) by pouring cold or warm water into the ear. Also available is bi-thermal air caloric irrigations, in which warm and cool air is administered into the ear.

Role in diagnosing brainstem death

The vestibulo-ocular reflex is tested by the caloric test. No eye movements are seen during or following the slow injection of at least 50 ml of ice-cold water over 60 s into each external auditory meatus in turn. Clear access to the tympanic membrane must be established by direct inspection, and the head should be at 30° to the horizontal plane, unless this positioning is contraindicated by the presence of an unstable spinal injury. Testing of the reflex forms part of the confirmation of a diagnosis of brainstem death. Diagnosing brainstem death requires a certain code of practice, written by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges.[15]

Related terms

Cervico-ocular reflex

Summary: Cervico-ocular reflex, also known by its acronym COR, involves the achievement of stabilization of a visual target,[16] and image on the retina, through adjustments of gaze impacted by neck and, or head movements or rotations. The process works in conjunction with the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR).[17]

See also

References

- "Vestibular nystagmus". www.dizziness-and-balance.com.

- "Sensory Reception: Human Vision: Structure and function of the Human Eye" vol. 27, p. 179 Encyclopædia Britannica, 1987

- Crawford JD, Vilis T (March 1991). "Axes of eye rotation and Listing's law during rotations of the head". Journal of Neurophysiology. 65 (3): 407–23. doi:10.1152/jn.1991.65.3.407. PMID 2051188.

- "VOR (Slow and Fast) | NOVEL - Daniel Gold Collection". collections.lib.utah.edu. Retrieved 2019-10-03.

- Angelaki DE (July 2004). "Eyes on target: what neurons must do for the vestibuloocular reflex during linear motion". Journal of Neurophysiology. 92 (1): 20–35. doi:10.1152/jn.00047.2004. PMID 15212435.

- Straka H, Dieringer N (July 2004). "Basic organization principles of the VOR: lessons from frogs". Progress in Neurobiology. 73 (4): 259–309. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.05.003. PMID 15261395.

- Cannon SC, Robinson DA (May 1987). "Loss of the neural integrator of the oculomotor system from brain stem lesions in monkey". Journal of Neurophysiology. 57 (5): 1383–409. doi:10.1152/jn.1987.57.5.1383. PMID 3585473.

- Crawford JD, Cadera W, Vilis T (June 1991). "Generation of torsional and vertical eye position signals by the interstitial nucleus of Cajal". Science. 252 (5012): 1551–3. Bibcode:1991Sci...252.1551C. doi:10.1126/science.2047862. PMID 2047862.

- Aw ST, Halmagyi GM, Haslwanter T, Curthoys IS, Yavor RA, Todd MJ (December 1996). "Three-dimensional vector analysis of the human vestibuloocular reflex in response to high-acceleration head rotations. II. responses in subjects with unilateral vestibular loss and selective semicircular canal occlusion". Journal of Neurophysiology. 76 (6): 4021–30. doi:10.1152/jn.1996.76.6.4021. PMID 8985897.

- "PsycNET". psycnet.apa.org. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- Ackerley R, Barnes GR (April 2011). "The interaction of visual, vestibular and extra-retinal mechanisms in the control of head and gaze during head-free pursuit". The Journal of Physiology. 589 (Pt 7): 1627–42. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2010.199471. PMC 3099020. PMID 21300755.

- Schmäl F, Thiede O, Stoll W (September 2003). "Effect of ethanol on visual-vestibular interactions during vertical linear body acceleration". Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 27 (9): 1520–6. doi:10.1097/01.ALC.0000087085.98504.8C. PMID 14506414.

- Gold, Daniel. "VOR (Slow and Fast)". Neuro-Ophthalmology Virtual Education Library (NOVEL): Daniel Gold Collection. Spencer S. Eccles Health Sciences Library. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- McGarvie LA, MacDougall HG, Halmagyi GM, Burgess AM, Weber KP, Curthoys IS (2015-07-08). "The Video Head Impulse Test (vHIT) of Semicircular Canal Function - Age-Dependent Normative Values of VOR Gain in Healthy Subjects". Frontiers in Neurology. 6: 154. doi:10.3389/fneur.2015.00154. PMC 4495346. PMID 26217301.

- Oram, John; Murphy, Paul (2011-06-01). "Diagnosis of death". Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain. 11 (3): 77–81. doi:10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkr008. ISSN 1743-1816.

- Schubert, Michael C. (December 2010) "The cervico-ocular reflex". Handbook of Clinical Neurophysiology.

- Kelders, W P A ; Kleinrensink; G J , van der Geest, J N ; Feenstra, L ; de Zeeuw, C I ; Frens, M. (November 2003). Compensatory increase of the cervico-ocular reflex with age in healthy humans.

External links

- (Video) Head Impulse Testing site (vHIT) Site with thorough information about vHIT

- Motor Learning in the VOR in Mice at edboyden.org

- Review on VOR adaptation via slides at Johns Hopkins University

- Vestibulo-Ocular+Reflex at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology - Testing device development

- ent/482 at eMedicine - "Vestibuloocular Reflex Testing"

- Depiction of Oculocephalic and Caloric reflexes

- Mueller-Jensen A, Neunzig HP, Emskötter T (April 1987). "Outcome prediction in comatose patients: significance of reflex eye movement analysis". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 50 (4): 389–92. doi:10.1136/jnnp.50.4.389. PMC 1031870. PMID 3585347.

- Vestibular nystagmus

- Videos of animals demonstrating VOR