Novichok agent

Novichok (Russian: Новичо́к, "newcomer"/ "newbie"[1]/ "novice, beginner/ new boy"[2]) is a series of binary chemical weapons developed by the Soviet Union and Russia between 1971 and 1993.[lower-alpha 1][4][5] Russian scientists who developed the nerve agents claim they are the deadliest ever made, with some variants possibly five to eight times more potent than VX,[6][7] and others up to ten times more potent than soman.[8]

| Part of a series on | |||||

| Chemical agents | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lethal agents | |||||

|

Blood

|

|||||

|

Blister

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

Nettle

|

|||||

|

Pulmonary/choking

|

|||||

|

Vomiting

|

|||||

| Incapacitating agents | |||||

|

|||||

| |||||

They were designed as part of a Soviet programme codenamed FOLIANT.[3][9] Five Novichok variants are believed to have been adapted for military use.[10] The most versatile is A-232 (Novichok-5).[11] Novichok agents have never been used on the battlefield. The UK government determined that a novichok agent was used in the poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal in Salisbury, Wiltshire, England in March 2018. It was unanimously confirmed by four laboratories around the world, according to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).[12] Novichok was also involved in the poisoning of a British couple in Amesbury, Wiltshire, four months later, believed to have been caused by nerve agent discarded after the Salisbury attack.[13] The attacks led to the death of one person,[14] left three others in a critical condition from which they recovered, and briefly hospitalised a police officer. Russia denies producing or researching agents "under the title Novichok".[15]

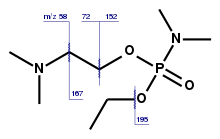

Novichok has however been known to most western secret services ever since the 1990s[16] and in 2016, Iranian chemists synthesised five Novichok agents for analysis and produced detailed mass spectral data which was added to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons Central Analytical Database.[17][18] Previously, there had been no detailed descriptions of their spectral properties in open scientific literature.[17][19] A small amount of agent A-230 was also claimed to have been synthesised in the Czech Republic in 2017 for the purpose of obtaining analytical data to help defend against these novel toxic compounds.[20]

Design objectives

These agents were designed to achieve four objectives:[21][22]

- to be undetectable using standard 1970s and 1980s NATO chemical detection equipment;

- to defeat NATO chemical protective gear;

- to be safer to handle; and

- to circumvent the Chemical Weapons Convention list of controlled precursors, classes of chemical and physical form.[23]

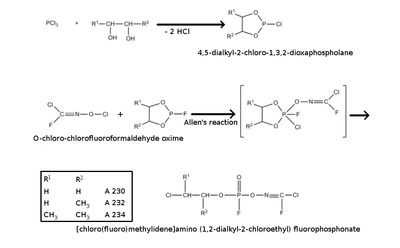

Some of these agents are binary weapons, in which precursors for the nerve agents are mixed in a munition to produce the agent just prior to its use. The precursors are generally significantly less hazardous than the agents themselves, so this technique makes handling and transporting the munitions a great deal simpler. Additionally, precursors to the agents are usually much easier to stabilise than the agents themselves, so this technique also makes it possible to increase the shelf life of the agents. This has the disadvantage that careless preparation may produce a non-optimal agent. During the 1980s and 1990s, binary versions of several Soviet agents were developed and are designated as "Novichok" agents.

History and disclosure

The Soviet Union and Russia reportedly developed extremely potent fourth-generation chemical weapons from the 1970s until the early 1990s, according to a publication by two chemists, Lev Fyodorov and Vil Mirzayanov in Moskovskiye Novosti weekly in 1992.[24][25][lower-alpha 2] The publication appeared just on the eve of Russia's signing of the Chemical Weapons Convention. According to Mirzayanov, the Russian Military Chemical Complex (MCC) was using defence conversion money received from the West for development of a chemical warfare facility.[6][7] Mirzayanov made his disclosure out of environmental concerns. He was the head of a counter-intelligence department and performed measurements outside the chemical weapons facilities to make sure that foreign spies could not detect any traces of production. To his horror, the levels of deadly substances were eighty times greater than the maximum safe concentration.[7][27]

Russian military industrial complex authorities admitted the existence of Novichok agents when they brought a treason case against Mirzayanov. According to expert witness testimonies that three scientists prepared for the KGB, Novichok and other related chemical agents had indeed been produced and therefore Mirzayanov's disclosure represented high treason.[lower-alpha 3]

Mirzayanov was arrested on 22 October 1992 and sent to Lefortovo prison for divulging state secrets. He was released later because "not one of the formulas or names of poisonous substances in the Moscow News article was new to the Soviet press, nor were locations ... of testing sites revealed."[7] According to Yevgenia Albats, "the real state secret revealed by Fyodorov and Mirzayanov was that generals had lied—and were still lying—to both the international community and their fellow citizens."[7] Mirzayanov now lives in the U.S.[29]

Further disclosures followed when Vladimir Uglev, one of Russia's leading binary weapons scientists, revealed the existence of A-232/Novichok-5 in an interview with the magazine Novoye Vremya in early 1994.[30] In his 1998 interview with David E. Hoffman for The Washington Post the chemist claimed that he helped invent the A-232 agent, that it was more frostproof, and confirmed that a binary version has been developed from it.[31] Uglev revealed more details in 2018, following the poisoning of the Skripals, stating that "several hundred" compounds were synthesised during the Foliant research but only four agents were weaponised (presumably the Novichok-5, -7, -8 and -9 mentioned by other sources): the first three were liquids and only the last, which was not developed until 1980, could be made into a powder. Unlike the interview twenty years earlier, he denied any binary agents were developed successfully, at least up until his involvement in the research ceased in 1994.[32]

In the 1990s, the German Federal Intelligence Service (BND) obtained a sample of a Novichok agent from a Russian scientist, and the sample was analysed in Sweden, according to a 2018 Reuters report. The chemical formula was given to Western NATO countries, who used small amounts to test protective and testing equipment, and antidotes.[33]

Novichok was referred to in a patent filed in 2008 for an organophosphorus poisoning treatment. The University of Maryland, Baltimore research was part-funded by the U.S. Army.[34]

Leonid Rink, who said he had done his doctoral dissertation research on the Novichok agents,[35] confirmed that the structures leaked by Mirzayanov were the correct ones.[36] Leonid Rink was himself convicted in Russia in 1994 for illegally selling the agent.[37][38]

David Wise, in his book Cassidy's Run, implies that the Soviet program may have been the unintended result of misleading information, involving a discontinued American program to develop a nerve agent code named "GJ", that was fed by a double agent to the Soviets as part Operation Shocker.[39]

Development and test sites

Stephanie Fitzpatrick, an American geopolitical consultant, has claimed that the Chemical Research Institute in Nukus, Soviet Uzbekistan[40] produced Novichok agents and The New York Times has reported that U.S. officials said the site was the major research and testing site for Novichok agents.[41][42] Small, experimental batches of the weapons may have been tested on the nearby Ustyurt Plateau.[42] Fitzpatrick also writes that the agents may have been tested in a research centre in Krasnoarmeysk near Moscow.[40] Precursor chemicals were made at the Pavlodar Chemical Plant in Soviet Kazakhstan, which was also thought to be the intended Novichok weapons production site, until its still-under-construction chemical warfare agent production building was demolished in 1987 in view of the forthcoming 1990 Chemical Weapons Accord and the Chemical Weapons Convention.[43][44]

Since its independence in 1991, Uzbekistan has been working with the government of the United States to dismantle and decontaminate the sites where the Novichok agents and other chemical weapons were tested and developed.[40][42] Between 1999[45] and 2002 the United States Department of Defense dismantled the major research and testing site for Novichok at the Chemical Research Institute in Nukus, under a $6 million Cooperative Threat Reduction programme.[41][46]

Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, a British chemical weapons expert and former commanding officer of the UK's Joint Chemical, Biological, Radiation and Nuclear Regiment and its NATO equivalent, "dismissed" suggestions that Novichok agents could be found in other places in the former Soviet Union such as Uzbekistan and has asserted that Novichok agents were produced only at Shikhany in Saratov Oblast, Russia.[47] Mirzayanov also says that it was at Shikhany, in 1973, that scientist Pyotr Petrovich Kirpichev first produced Novichok agents; Vladimir Uglev joined him on the project in 1975.[48] According to Mirzayanov, while production took place in Shikhany, the weapon was tested at Nukus between 1986 and 1989.[6]

Following the poisoning of the Skripals, former head of the GosNIIOKhT security department Nikolay Volodin confirmed in an interview to Novaya Gazeta that there have been tests at Nukus, and said that dogs were used.[49]

In May 2018, the Irish Independent reported that "Germany's foreign intelligence service secured a sample of the Soviet-developed nerve agent Novichok in the 1990s and passed on its knowledge to partners including Britain and the US, according to German media reports." The sample was analysed in Sweden.[50] Small amounts of the Novichok nerve agent were subsequently produced in some NATO countries for test purposes.[51]

Description of Novichok agents

Mirzayanov provided the first description of these agents.[27] Dispersed in an ultra-fine powder instead of a gas or a vapour, they have unique qualities. A binary agent was then created that would mimic the same properties but would either be manufactured using materials which are not controlled substances under the CWC,[29] or be undetectable by treaty regime inspections.[42] The most potent compounds from this family, Novichok-5 and Novichok-7, are supposedly around five to eight times more potent than VX.[58] The "Novichok" designation refers to the binary form of the agent, with the final compound being referred to by its code number (e.g. A-232). The first Novichok series compound was in fact the binary form of a known V-series nerve agent, VR,[58] while the later Novichok agents are the binary forms of compounds such as A-232 and A-234.[59]

According to a classified (secret) report by the US Army National Ground Intelligence Center in Military Intelligence Digest dated 24 January 1997,[60] agent designated A-232 and its ethyl analogue A-234 developed under the Foliant programme "are as toxic as VX, as resistant to treatment as soman, and more difficult to detect and easier to manufacture than VX". The binary versions of the agents reportedly use acetonitrile and an organic phosphate "that can be disguised as a pesticide precursor."

Mirzayanov gives somewhat different structures for Novichok agents in his autobiography to those which have been identified by Western experts.[61] He makes clear that a large number of compounds were made, and many of the less potent derivatives were reported in the open literature as new organophosphate insecticides,[62] so that the secret chemical weapons program could be disguised as legitimate pesticide research.

The agent A-234 is also supposedly around five to eight times more potent than VX.[63][58]

The agents are reportedly capable of being delivered as a liquid, aerosol or gas via a variety of systems, including artillery shells, bombs, missiles and spraying devices.[40]

Chemistry

According to chemical weapons expert Jonathan Tucker, the first binary formulation developed under the Foliant programme was used to make Substance 33 (VR), very similar to the more widely-known VX, differing only in the alkyl substituents on its nitrogen and oxygen atoms. "This weapon was given the code name Novichok."[64]

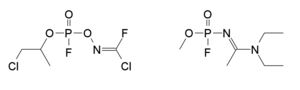

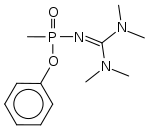

A wide range of potential structures have been reported. These all feature the classical organophosphorus core (sometimes with the P=O replaced with P=S or P=Se), which is most commonly depicted as being a phosphoramidate or phosphonate, usually fluorinated (cf. monofluorophosphate). The organic groups are subject to more variety; however, a common substituent is phosgene oxime or analogues thereof. This is a potent chemical weapon in its own right, specifically as a nettle agent, and would be expected to increase the harm done by the Novichok agent. Many claimed structures from this group also contain cross-linking agent motifs which may covalently bind to the acetylcholinesterase enzyme's active site in several places, perhaps explaining the rapid denaturing of the enzyme that is claimed to be characteristic of the Novichok agents.

Zoran Radić, a chemist at the University of California, San Diego, performed an in silico docking study with Mirzayanov's version of the A-232 structure against the active site of the acetylcholinesterase enzyme. The model predicted a tight fit with high binding affinity and formation of a covalent bond to a serine residue in the active site, with a similar binding mode to established nerve agents such as sarin and soman.[66]

Lifetime

According to Vladimir Uglyov, who worked on the development of Novichok, it is very stable with a slow evaporation rate and can remain dangerous for years once deployed.[67] Insufficient research has been done to fully understand its persistence in various situations in the environment.[68]

Effects and countermeasures

As nerve agents, the Novichok agents belong to the class of organophosphate acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. These chemical compounds inhibit the enzyme acetylcholinesterase, preventing the normal breakdown of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Acetylcholine concentrations then increase at neuromuscular junctions to cause involuntary contraction of all skeletal muscles (cholinergic crisis). This then leads to respiratory and cardiac arrest (as the victim's heart and diaphragm muscles no longer function normally) and finally death from heart failure or suffocation as copious fluid secretions fill the victim's lungs.[69]

As can be seen with other organophosphate poisonings, Novichok agents may cause lasting nerve damage, resulting in permanent disablement of victims, according to Russian scientists.[70] Their effect on humans was demonstrated by the accidental exposure of Andrei Zheleznyakov, one of the scientists involved in their development, to the residue of an unspecified Novichok agent while working in a Moscow laboratory in May 1987. He was critically injured and took ten days to recover consciousness after the incident. He lost the ability to walk and was treated at a secret clinic in Leningrad for three months afterwards. The agent caused permanent harm, with effects that included "chronic weakness in his arms, a toxic hepatitis that gave rise to cirrhosis of the liver, epilepsy, spells of severe depression, and an inability to read or concentrate that left him totally disabled and unable to work." He never recovered and, after five years of deteriorating health, died in July 1992.[71]

The use of a fast-acting peripheral anticholinergic drug such as atropine can block the receptors where acetylcholine acts to prevent poisoning (as in the treatment for poisoning by other acetylcholinesterase inhibitors). Atropine, however, is difficult to administer safely, because its effective dose for nerve agent poisoning is close to the dose at which patients suffer severe side effects, such as changes in heart rate and thickening of the bronchial secretions, which fill the lungs of someone suffering nerve agent poisoning so that suctioning of these secretions, and other advanced life support techniques, may be necessary in addition to administration of atropine to treat nerve agent poisoning.[69]

In the treatment of nerve agent poisoning, atropine is most often administered along with a Hagedorn oxime such as pralidoxime, obidoxime, TMB-4, or HI-6, which reactivates acetylcholinesterase which has been inactivated by phosphorylation by an organophosphorus nerve agent and relieves the respiratory muscle paralysis caused by some nerve agents. Pralidoxime is not effective in reactivating acetylcholinesterase inhibited by some older nerve agents such as soman[69] or the Novichok nerve agents, described in the literature as being up to eight times more toxic than nerve agent VX.[55]

The US Army has funded studies of the use of galantamine along with atropine in the treatment of a number of nerve agents, including soman and the Novichok agents. An unexpected synergistic interaction was seen to occur between galantamine (given between five hours before to thirty minutes after exposure) and atropine in an amount of 6 mg/kg or higher. Increasing the dose of galantamine from 5 to 8 mg/kg decreased the dose of atropine needed to protect experimental animals from the toxicity of soman in dosages 1.5 times the LD50 (lethal dose in half the animals studied).[34]

There have been differing claims about the persistence of Novichok and binary precursors in the environment. One view is that it is not affected by normal weather conditions, and may not decompose as quickly as other organophosphates. However, Mirzayanov states that Novichok decomposes within four months.[72][73]

Uses

Poisoning of Ivan Kivelidi and Zara Ismailova

The forerunner of Novichok agents, substance-33 (frequently also referred to simply as "Novichok")[75] has been reportedly used in 1995 to poison Russian banker Ivan Kivelidi, the head of the Russian Business Round Table, with close ties to the then Russian Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin,[76] and Zara Ismailova, his secretary.[77][78][79][80][81] Russian opposition-linked historians Yuri Felshtinsky and Vladimir Pribylovsky speculated that the murder became "one of the first in the series of poisonings organised by Russia's security services". The Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs analysed the substance and announced that it was "a phosphorus-based military-grade nerve agent"[82] "whose formula was strictly classified".[82] According to Nesterov, the administrative head of Shikhany, he did not know of "a single case of such poison being sold illegally" and noted that the poison "is used by professional spies".[82]

Vladimir Khutsishvili, a former business partner of the banker, was subsequently convicted of the killings.[77] According to The Independent, "A closed trial found that his business partner had obtained the substance via intermediaries from an employee of the State Research Institute of Organic Chemistry and Technology (GosNIIOKhT),[83] which was involved in the development of Novichoks. However, Khutsishvilli, who claimed that he was innocent, had not been detained at the time of the trial and freely left the country. He was only arrested in 2006 after he returned to Russia, believing that the ten-year old case was closed.[82] Felshtinsky and Pribylovsky claimed that Khutsishvilli was framed for the murder by Russia's security services, which had access to the chemical agent, and used it to organise the murder on the orders of a senior Russian state official.[82]

Leonid Rink, an employee of GosNIIOKhT, received a one-year suspended sentence for selling Novichok agents to unnamed buyers "of Chechen ethnicity" soon after the poisoning of Kivelidi and Izmailova.[84][85]

Poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal

On 12 March 2018, the UK government said that a Novichok agent had been used in an attack in the English city of Salisbury on 4 March 2018 in an attempt to kill former GRU officer Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia.[86] British Prime Minister Theresa May said in Parliament: "Either this was a direct action by the Russian state against our country, or the Russian government lost control of its potentially catastrophically damaging nerve agent and allowed it to get into the hands of others."[86] On 14 March 2018, the UK expelled 23 Russian diplomats after the Russian government refused to meet the UK's deadline of midnight on 13 March 2018 to give an explanation for the use of the substance.[87]

After the attack, 21 members of the emergency services and public were checked for possible exposure, and three were hospitalised. As of 12 March, one police officer remained in hospital.[86] Five hundred members of the public were advised to decontaminate their possessions to prevent possible long-term exposure, and 180 members of the military and 18 vehicles were deployed to assist with decontamination at locations in and around Salisbury. Up to 38 people in Salisbury have been affected by the agent to an undetermined extent.[88] Addressing the United Nations Security Council, Vassily Nebenzia, the Russian envoy to the UN, responded to the British allegations by denying that Russia had ever produced or researched the agents, stating: "No scientific research or development under the title novichok were carried out."[15]

Daniel Gerstein, a former senior official at the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, said it was possible that Novichok nerve agents had been used before in Britain to assassinate Kremlin targets, but had not been detected: "It's entirely likely that we have seen someone expire from this and not realised it. We realised in this case because they were found unresponsive on a park bench. Had it been a higher dose, maybe they would have died and we would have thought it was natural causes."[89]

On 20 March 2018, Ahmet Üzümcü, Director-General of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), said that it would take "another two to three weeks to finalise the analysis" of samples taken from the poisoning of Skripal.[90]

On April 3, 2018, the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory announced that it was "completely confident" that the agent used was Novichok, although they still did not know the "precise source" of the agent. Experts said that their findings did not challenge the conclusions by UK government: "We provided that information to the Government who have then used a number of other sources to come to the conclusions that they have."[91]

On April 12, 2018 the OPCW announced that their investigations agreed with the conclusions made by the UK about the identity of the chemical used.[92]

Poisoning of Charlie Rowley and Dawn Sturgess

On 30 June 2018, Charlie Rowley and Dawn Sturgess were found unconscious at a house in Amesbury, Wiltshire, about eight miles from the Salisbury poisoning site.[93] On 4 July 2018, police said that the pair had been poisoned with the same nerve agent as ex-Russian spy Sergei Skripal.[94]

On 8 July 2018, Dawn Sturgess died as a result of the poisoning.[95] Rowley recovered consciousness, and was recovering in hospital.[96] He told his brother Matthew the nerve agent had been in a small perfume or aftershave bottle, which they had found in a park about nine days before spraying themselves with it. The police later closed and fingertip-searched Queen Elizabeth Gardens in Salisbury.[97]

See also

- Poison laboratory of the Soviet secret services

- Russia and weapons of mass destruction

References

Notes

- Jonathon B. Tucker writes that approval to commence research into "fourth generation" chemical weapons was given by the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the Soviet Council of Ministers in May 1971. Vil Mirzayanov, the Russian scientist who first alerted the West to the existence of the Novichok agents, states that testing of Novichok-7 was successfully completed in 1993—after the signing of the Chemical Weapons Convention but before Russia ratified the treaty and when it came into force.[3][4]

- Mirzayanov had made a similar disclosure a year earlier in the 10 October 1991 issue of the Moscow newspaper, Kuranty.[26]

- "[T]he talk [by Mirzayanov] about binary weapons was no more than a verbal construct, an argument ex adverso, and only the MCC [Russian Military Chemical Complex] could corroborate or refute this natural assumption. By entangling V. S. Mirzayanov in the investigation, the MCC confirmed the stated hypothesis, advancing it to the ranks of proven facts."[28]

Citations

- "What are Novichok nerve agents and did Russia do it?".

- Oxford Russian Dictionary (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. 2000. p. 265.

- Tucker 2006, p. 231

- Mirzayanov, Vil (1995), "Dismantling the Soviet/Russian Chemical Weapons Complex: An Insider's View", Global Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction: Hearings Before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Governmental Affairs, 104th Cong., pp. 393–405

- Tucker 2006, pp. 231–233

- Birstein 2004, p. 110

- Albats 1994, pp. 325–328

- Croddy, Wirtz & Larsen 2001, p. 201

- Pitschmann 2014, p. 1765

- Tucker 2006, p. 233

- Tucker 2006, p. 253

- Benjamin Kentish (12 April 2018). "Poison used on Sergei and Yulia Skripal in Salisbury attack was novichok nerve agent, confirms chemical weapons watchdog". The Independent.

- "Wiltshire pair poisoned by Novichok nerve agent". BBC News. 4 July 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "Novichok: Murder inquiry after Dawn Sturgess dies".

- Borger, Julian (15 March 2018). "UK spy poisoning: Russia tells UN it did not make nerve agent used in attack". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "'Unknown' newcomer novichok was long known". NRC. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- Ryan De Vooght-Johnson (1 January 2017). "Iranian chemists identify Russian chemical warfare agents". spectroscopyNOW.com. Wiley. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Hosseini SE, Saeidian H, Amozadeh A, Naseri MT, Babri M (5 October 2016). "Fragmentation pathways and structural characterization of organophosphorus compounds related to the Chemical Weapons Convention by electron ionization and electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry". Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 30 (24): 2585–2593. doi:10.1002/rcm.7757. PMID 27704643.

- Report of the Scientific Advisory Board on developments in science and technology for the Third Review Conference (PDF) (Report). Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. 27 March 2013. p. 3. RC-3/WP.1. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "Земан: в Чехии производился и складировался нервно-паралитический газ "Новичок"".

- Salem & Katz 2014, pp. 498–499

- Kendall et al. 2008, p. 136

- "Novichok agent". ScienceDirect. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

The Novichok class of agents were reportedly developed in an attempt to circumvent the Chemical Weapons Treaty (chemical weapons are banned on the basis of chemical structure and therefore a new chemical agent is not subject to past treaties). They have reportedly been engineered to be undetectable by standard detection equipment and to defeat standard chemical protective gear...Novichok agents may consist of two separate 'non-toxic' components that, when mixed, become the active nerve agent...The binary concept—mixing or storing two less toxic chemicals and creating the nerve agent within the weapon—was safer during storage.

- Darling & Noste 2016

- Fyodorov, Lev; Mirzayanov, Vil (20 September 1992). "A Poison Policy". Moscow News (39).

- "News Chronology: August through November 1992" (PDF), Chemical Weapons Convention Bulletin (18), p. 14, December 1992, retrieved 18 March 2018

- "Chemical Weapons Disarmament in Russia: Problems and Prospects; Dismantling the Soviet/Russian Chemical Weapons Complex: An Insider's View". Henry L. Stimson Center, Washington, D.C. 13 October 1995.

- Fedorov, Lev (27 July 1994), Chemical Weapons in Russia: History, Ecology, Politics, retrieved 13 March 2018

- Hoffman, David (16 August 1998). "Wastes of War: Soviets Reportedly Built Weapon Despite Pact". The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- Waller, J. Michael (13 February 1997). "The Chemical Weapons Coverup". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "WashingtonPost.com: Cold War Report". The Washington Post.

- Svetlana Reiter; Natalia Gevorkyan (20 March 2018). "The scientist who developed "Novichok": "Doses ranged from 20 grams to several kilos"". thebell.io.

- Sabine Siebold, Andrea Shalal (16 May 2018). "West's knowledge of Novichok came from sample secured in 1990s: report". Reuters. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- "Method of Treating Organophosphorous Poisoning". United States Patent and Trademark Office. 22 January 2009. Patent Application 20090023706. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- Cockburn H. (20 March 2018). "Soviet-era scientists contradict Moscow's claims Russia never made Novichok nerve agent". The Independent.

- "Boris Johnson compares Russian World Cup to Hitler's 1936 Olympics". stuff.co.nz. 22 March 2018.

- "Nerve agent was used in 1995 murder, claims former Soviet scientist".

- "Secret trial shows risks of nerve agent theft in post-Soviet chaos: experts". Reuters. 20 March 2018.

- Flynn, Michael; Garthoff, Raymond L. (2000). "Playing with Fire". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 56 (5): 35–40. Bibcode:2000BuAtS..56e..35F. doi:10.1080/00963402.2000.11456992.

- Croddy, Wirtz & Larsen 2001, pp. 201–202

- Miller, Judith (25 May 1999). "U.S. and Uzbeks Agree on Chemical Arms Plant Cleanup". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Hidalgo, Louise (9 August 1999). "US dismantles chemical weapons". BBC News. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- "Kazakhstan – Chemical". Nuclear Threat Initiative. April 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Bozheyeva, Gulbarshyn (Summer 2000). The Pavlodar Chemical Weapons Plant in Kazakhstan: History and Legacy (PDF) (Report). The Nonproliferation Review. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Hogan, Beatrice (19 August 1999). "Uzbekistan: U.S. Begins Survey Of Chemical Weapons Plant". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Wolf, John S. (19 March 2003). "Hearing, First Session". Committee on Foreign Relations. United States Senate. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

Hon. John S. Wolf, Assistant Secretary of State for Nonproliferation: ... DOD completed a project to dismantle the former Soviet CW research facility at Nukus, Uzbekistan in FY 2002.

- MacAskill, Ewen (14 March 2018). "Novichok: nerve agent produced at only one site in Russia, says expert". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- Wise 2000, p. 273

- "'Новичок'—это слишком для одного Скрипаля". Novaya Gazeta. 22 March 2018.

- "Germany obtained sample of Novichok in the 1990s, reports suggest". Irish Independent. 18 May 2018.

- "West's knowledge of Novichok came from sample secured in 1990s: report". Reuters. 18 May 2018.

- Hoenig 2007, pp. 79–80

- Mirzayanov 2008, pp. 142–145, 179–180

- Ellison 2008, pp. 37–42

- Gupta 2015, pp. 339–340

- Konopski L., Historia broni chemicznej, Warszawa: Bellona, 2009, ISBN 978-83-11-11643-6

- Balali-Mood M, Abdollahim M. (Eds.), Basic and Clinical Toxicology of Organophosphorus Compounds, Springer 2014. ISBN 9781447156253

- Peplow, Mark (19 March 2018), "Nerve agent attack on spy used 'Novichok' poison", Chemical & Engineering News, 96 (12), p. 3, retrieved 16 March 2018

- Halámek E, Kobliha Z. POTENCIÁLNÍ BOJOVÉ CHEMICKÉ LÁTKY. Chemicke Listy 2011; 105(5):323–333

- Pike, John. "Russia dodges chemical arms ban By Bill Gertz THE WASHINGTON TIMES Tuesday". www.globalsecurity.org.

- Vásárhelyi, Györgyi; Földi, László (2007). "History of Russia's chemical weapons" (PDF). AARMS. 6 (1): 135–146.

- Sokolov VB, Martynov IV. Effect of Alkyl Substituents in Phosphorylated Oximes. Zhurnal Obshchei Khimii. 1987; 57(12):2720–2723.

- "Spy poisoning: Putin most likely behind attack – Johnson", BBC News, 16 March 2018, retrieved 16 March 2018

- Peplow, Mark (19 March 2018). "Nerve agent attack on spy used 'Novichok' poison". Chemical & Engineering News. 96 (12): 3. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- Emil Halámek and Zbynek Kobliha (May 2011). "Potential Chemical Warfare Agents". Chemicke Listy.

- Stone, R. (19 March 2018). "U.K. attack shines spotlight on deadly nerve agent developed by Soviet scientists". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aat6324. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- "This is how two people could have been poisoned with novichok again". The Independent. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- Hay, Prof Alastair (11 July 2018). "How long Novichok could remain a danger for". BBC News. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- Meridian Medical Technologies, Inc. (30 September 2009). "Label: DuoDote – atropine and pralidoxime chloride". Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- Stewart, Charles Edward (2006). Weapons of Mass Casualties and Terrorism Response Handbook. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 9780763724252.

- Tucker 2006, p. 273

- Nick Allen Helena Horton (5 July 2018). "Novichok in Salisbury: The public thought it was safe ... so how could this happen four months later?". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- "Amesbury Novichok poisoning: Couple exposed to nerve agent". BBC News. 5 July 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- Shleynov, Roman (23 March 2018). ""Новичок" уже убивал" ['Novichok' has already killed]. Novaya Gazeta (in Russian) (30). Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- "Secret trial shows risks of nerve agent theft in post-Soviet chaos:..." Reuters. 20 March 2018.

- "Murders panic Russian business elite". The Independent. 8 August 1995.

- Strokan, Sergey; Yusin, Maksim; Safronov, Ivan; Korostikov, Mikhail; Inyutin, Vsevolod (13 March 2018). "И яд следовал за ним" [And the poison followed him]. Kommersant (in Russian) (41). p. 1. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Stanley, Alessandra (9 August 1995). "To the Business Risks in Russia, Add Poisoning". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- McGregor 2011, p. 166

- "Theresa May accuses Russia of involvement in Skripal's poisoning, as Russian-made prohibited substance discovered". Crime Russia. 13 March 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Stewart, Will. "Were these the first victims of nerve agent Novichok? Russian banker and secretary 'assassinated' in mysterious circumstances 20 years ago". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Felshtinsky & Pribylovsky 2009, pp. 453–457

- "Secret trial shows risks of nerve agent theft in post-Soviet chaos - experts". Thomson Reuters Foundation. 20 March 2018.

- "Why is the UK accusing Russia of launching a nerve agent attack on Sergei Skripal in Salisbury, and what is the evidence?". The Independent. 16 March 2018.

- ""Novichok" has been already used for killing ("Новичок" уже убивал)". Novaya Gazeta. 22 March 2018.

- "Russian spy: Highly likely Moscow behind attack, says Theresa May". BBC News. 12 March 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "Russian spy: UK to expel 23 Russian diplomats". BBC News. 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Moran, Terry; Vlasto, Chris; Meek, James (18 March 2018). "Russian ex-spy's poisoning in UK believed from nerve agent in car vents; at least 38 others sickened: Sources". ABCNews.com. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

The intelligence officials told ABC News up to 38 individuals in Salisbury have been identified as having been affected by the nerve agent but the full impact is still being assessed and more victims sickened by the agent are expected to be identified

- Barry, Ellen; Yeginsu, Ceylan (13 March 2018). "The nerve agent too deadly to use—until someone did in Britain". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Two to three weeks to analyse samples from Salisbury attack: OPCW". Agence France-Presse. 20 March 2018.

- "Defence experts 'unsure' of source behind novichok spy attack". ITV. 3 April 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "OPCW Issues Report on Technical Assistance Requested by the United Kingdom". www.opcw.org. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- "Amesbury: Two collapse near Russian spy poisoning site". BBC News. 4 July 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "Pair 'poisoned by nerve agent'". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "UPDATE: Woman dies following exposure to nerve agent in Amesbury". Metropolitan Police. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Amesbury novichok victim's brother says nerve agent was 'found in perfume bottle'". Sky News. 17 July 2018.

- Steven Morris (18 July 2018). "Novichok poisonings: police search Salisbury park visited by couple". The Guardian.

Bibliography

- Albats, Yevgenia (1994), The State Within a State: The KGB and Its Hold on Russia — Past, Present, and Future, translated by Fitzpatrick, Catherine A., New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux, ISBN 978-0-374-18104-8

- Birstein, Vadim J. (2004), The Perversion Of Knowledge: The True Story of Soviet Science, Westview Press, ISBN 978-0-8133-4280-1

- Darling, Robert G.; Noste, Erin E. (2016), "Future Biological and Chemical Weapons", in Ciottone, Gregory R. (ed.), Ciottone's Disaster Medicine (Second ed.), Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 489–498, doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-28665-7.00080-7, ISBN 9780323286657

- Croddy, Eric A.; Wirtz, James J.; Larsen, Jeffrey A., eds. (2001), Weapons of Mass Destruction: The Essential Reference Guide, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-851-09490-5

- Ellison, D. Hank (2008), Handbook of Chemical and Biological Warfare Agents (Second ed.), CRC Press, ISBN 978-0-849-31434-6

- Felshtinsky, Yuri; Pribylovsky, Vladimir (2009), The Corporation: Russia and the KGB in the Age of President Putin, London: Encounter Books, ISBN 978-1-594-03246-2

- Gupta, Ramesh C., ed. (2015), Handbook of Toxicology of Chemical Warfare Agents, Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, ISBN 978-0-128-00494-4

- Hoenig, Steven L. (2007), Compendium of Chemical Warfare Agents, Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-34626-7

- Kendall, Ronald J.; Presley, Steven M.; Austin, Galen P.; Smith, Philip N. (2008), Advances in Biological and Chemical Terrorism Countermeasures, CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-420-07654-7

- McGregor, Paul (2011), Toxic Politics: The Secret History of the Kremlin's Poison Laboratory—from the Special Cabinet to the Death of Litvinenko, Praeger, ISBN 978-0-313-38746-3

- Mirzayanov, Vil S. (2008), State Secrets: An Insider's Chronicle of the Russian Chemical Weapons Program, Outskirts Press, ISBN 978-1-4327-2566-2

- Pitschmann, Vladimír (2014), "Overall View of Chemical and Biochemical Weapons", Toxins, 6 (6): 1761–1784, doi:10.3390/toxins6061761, PMC 4073128, PMID 24902078

- Salem, Harry; Katz, Sidney A., eds. (2014), Inhalation Toxicology (3rd ed.), CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-466-55273-9

- Tucker, Jonathon B. (2006), War of Nerves, New York: Anchor Books, ISBN 978-0-375-42229-4

- Wise, David (2000), Cassidy's Run: The Secret Spy War Over Nerve Gas, Thorndike, ME: G.K. Hall & Co, ISBN 978-0-783-89144-6

Further reading

- Kincaid, Cliff (February 1995), "Russia's Dirty Chemical Secret", American Legion Magazine, American Legion, 138 (2), pp. 32–34, 58

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Novichok agents. |

- Fedorov, Lev (27 July 1994). "Chemical Weapons in Russia: History, Ecology, Politics". Federation of American Scientists.

- "Russian chemical weapons". Federation of American Scientists.