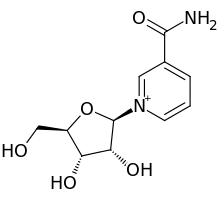

Nicotinamide riboside

Nicotinamide riboside (NR) is claimed to be a new form pyridine-nucleoside of vitamin B3 that functions as a precursor to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide or NAD+.[1][2]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

1-(β-D-Ribofuranosyl)nicotinamide; N-Ribosylnicotinamide | |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number |

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula |

C11H15N2O5+ |

| Molar mass | 255.25 g/mol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Chemistry

While the molecular weight of nicotinamide riboside is 255.25 g/mol,[3] that of its chloride salt is 290.70 g/mol.[4][5] As such, 100 mg of nicotinamide riboside chloride provides 88 mg of nicotinamide riboside.

History

Nicotinamide riboside (NR) was first described in 1944 as a growth factor, termed Factor V, for Haemophilus influenza, a bacterium that lives in and depends on blood. Factor V, purified from blood, was shown to exist in three forms: NAD+, NMN and NR. NR was the compound that led to the most rapid growth of this bacterium.[6] Notably, H. influenza cannot grow on nicotinic acid, nicotinamide, tryptophan or aspartic acid, which were the previously known precursors of NAD+.[7]

In 2000, yeast Sir2 was shown to be an NAD+-dependent protein lysine deacetylase,[8] which led several research groups to probe yeast NAD+ metabolism for genes and enzymes that might regulate lifespan. Biosynthesis of NAD+ in yeast was thought to flow exclusively through NAMN (nicotinic acid mononucleotide).[9][10][11][12][13]

When NAD+ synthase (glutamine-hydrolysing) was deleted from yeast cells, NR permitted yeast cells to grow. Thus, these Dartmouth College investigators proceeded to clone yeast and human nicotinamide riboside kinases and demonstrate the conversion of NR to NMN by nicotinamide riboside kinases in vitro and in vivo. They also demonstrated that NR is a natural product found in cow's milk.[14][15]

Properties

Although it is a form of vitamin B3, NR exhibits unique properties that distinguish it from the other B3 vitamins—niacin and nicotinamide. In a head-to-head experiment conducted on mice, each of these vitamins exhibited unique effects on the hepatic NAD+ metabolome with unique kinetics, and with NR as the form of B3 that produced the greatest increase in NAD+ at a single timepoint.[16]

Different biosynthetic pathways are responsible for converting the different B3 vitamins into NAD+. The enzyme nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (Nampt) catalyzes the rate-limiting step of the two-step pathway converting nicotinamide to NAD+. Two nicotinamide riboside kinases (NRK1 and NRK2) convert NR to NAD+ via a pathway that does not require Nampt.[14]

Animal studies have demonstrated that these enzymes respond differently to age and stress. In a mouse model of dilated cardiomyopathy, NRK2 mRNA expression increased, while Nampt mRNA expression decreased.[17] A similar increase in NRK1 and NRK2 expression has been observed in injured central and peripheral neurons.[18][19][20][21][22]

Niacin is known for its tendency to cause an uncomfortable flushing of the skin. This flushing is triggered by the activation of the GPR109A G-protein coupled receptor. NR does not activate this receptor,[23] and has not been shown to cause flushing in humans—even at doses as high as 2,000 mg/day.[16][24][25][26]

Despite being an NAD+ precursor, nicotinamide acts as an inhibitor of the NAD+-consuming sirtuin enzymes.[10] When sirtuins consume NAD+, they create nicotinamide and O-acetyl-ADP-ribose as products of the deacetylation reaction. Consistent with high-dose nicotinamide as a sirtuin inhibitor, NR and niacin, but not nicotinamide, have been shown to increase hepatic levels of O-acetyl-ADP-ribose.[16]

Commercialization

In 2004, Dartmouth Medical School researcher Dr. Charles Brenner discovered that NR could be converted to NAD+ via the eukaryotic nicotinamide riboside kinase biosynthetic pathway[14] Dartmouth was subsequently issued patents for nutritional and therapeutic uses of NR, in 2006.[27] ChromaDex licensed these patents in July 2012, and began to develop a commercially viable, full-scale process to bring NR to market.[28] ChomaDex has been in a patent dispute with Elysium Health over the rights to a nicotinamide riboside supplements.[29]

Human Clinical Testing

There have been five published clinical trials on groups of both men and women testing for safety. One of these trials studied NR in combination with pterostilbene,[30] while the other four examined the effects of NR alone.[16][24][25][26]

The first published clinical trial established the safety and characterized the pharmacokinetics of single doses of NR.[16] Since then, doses as high as 2,000 mg/day have been administered over periods as long as 12 weeks.[25] These studies show that NR can significantly increase levels of NAD+ and some of its associated metabolites in both whole blood and peripheral blood mononuclear cells.[16][24][26]

In a 12 week clinical trial of obese insulin-resistant men using 2000 mg/day, NR appeared safe, but did not improve insulin sensitivity or whole-body glucose metabolism.[26] In a trial of NR 250 mg plus 50 mg of pterostilbene, as well as with double this dose, the combined supplement raised NAD+ levels in a trial of older adults.[30]

See also

- Nicotinamide mononucleotide

- Niacin

- Nicotinamide

- Vitamin B3

- Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- Sirtuin

- Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

References

- Bogan, K.L., Brenner, C. (2008). "Nicotinic acid, nicotinamide, and nicotinamide riboside: a molecular evaluation of NAD+ precursor vitamins in human nutrition". Annu. Rev. Nutr. 28: 115–130. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155443. PMID 18429699.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Chi Y, Sauve AA (November 2013). "Nicotinamide riboside, a trace nutrient in foods, is a vitamin B3 with effects on energy metabolism and neuroprotection". Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 16 (6): 657–61. doi:10.1097/MCO.0b013e32836510c0. PMID 24071780.

- "Nicotinamide riboside". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- "GRAS Notices, GRN No. 635". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- "Spherix/ChromaDex GRAS submission" (PDF). FDA.gov. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- Gingrich, W; Schlenk, F (June 1944). "Codehydrogenase I and Other Pyridinium Compounds as V-Factor for Hemophilus influenzae and H. parainfluenzae". Journal of Bacteriology. 47 (6): 535–50. PMC 373952. PMID 16560803.

- Belenky, P.; et al. (2007). "NAD+ Metabolism in Health and Disease". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 32 (1): 12–19. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2006.11.006. PMID 17161604.

- Imai, S.; et al. (2000). "Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase". Nature. 403 (6771): 795–800. doi:10.1038/35001622. PMID 10693811.

- Anderson; et al. (2003). "Nicotinamide and PNC1 govern lifespan extension by calorie restriction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Nature. 423 (6936): 181–185. doi:10.1038/nature01578. PMC 4802858. PMID 12736687.

- Bitterman; et al. (2002). "Inhibition of silencing and accelerated aging by nicotinamide, a putative negative regulator of yeast Sir2 and human SIRT1". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (47): 45099–45107. doi:10.1074/jbc.m205670200. PMID 12297502.

- Gallo; et al. (2004). "Nicotinamide clearance by pnc1 directly regulates sir2-mediated silencing and longevity". Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 (3): 1301–1312. doi:10.1128/mcb.24.3.1301-1312.2004. PMC 321434.

- Panozzo, C.; et al. (2002). "Aerobic and anaerobic NAD+ metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". FEBS Lett. 517 (1–3): 97–102. doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02585-1. PMID 12062417.

- Sandmeier, JJ; Celic, I; Boeke, JD; Smith, JS (March 2002). "Telomeric and rDNA silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are dependent on a nuclear NAD(+) salvage pathway". Genetics. 160 (3): 877–89. PMC 1462005. PMID 11901108.

- Bieganowki, P. & Brenner, C. (2004). "Discoveries of Nicotinamide Riboside as a Nutrient and Conserved NRK Genes Establish a Preiss-Handler Independent Route to NAD+ in Fungi and Humans". Cell. 117 (4): 495–502. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00416-7. PMID 15137942.

- Hautkooper, R.H.; et al. (2012). "Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan". Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13 (4): 225–238. doi:10.1038/nrm3293. PMC 4872805. PMID 22395773.

- Trammell, Samuel A. J.; Schmidt, Mark S.; Weidemann, Benjamin J.; Redpath, Philip; Jaksch, Frank; Dellinger, Ryan W.; Li, Zhonggang; Abel, E. Dale; Migaud, Marie E.; Brenner, Charles (10 October 2016). "Nicotinamide riboside is uniquely and orally bioavailable in mice and humans". Nature Communications. 7 (1): 12948. doi:10.1038/ncomms12948. PMC 5062546. PMID 27721479.

- Diguet, Nicolas; Trammell, Samuel A.J.; Tannous, Cynthia; Deloux, Robin; Piquereau, Jérôme; Mougenot, Nathalie; Gouge, Anne; Gressette, Mélanie; Manoury, Boris; Blanc, Jocelyne; Breton, Marie; Decaux, Jean-François; Lavery, Gareth G.; Baczkó, István; Zoll, Joffrey; Garnier, Anne; Li, Zhenlin; Brenner, Charles; Mericskay, Mathias (22 May 2018). "Nicotinamide Riboside Preserves Cardiac Function in a Mouse Model of Dilated Cardiomyopathy". Circulation. 137 (21): 2256–2273. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026099. PMID 29217642.

- Vaur, Pauline; Brugg, Bernard; Mericskay, Mathias; Li, Zhenlin; Schmidt, Mark S.; Vivien, Denis; Orset, Cyrille; Jacotot, Etienne; Brenner, Charles; Duplus, Eric (December 2017). "Nicotinamide riboside, a form of vitamin B , protects against excitotoxicity-induced axonal degeneration". The FASEB Journal. 31 (12): 5440–5452. doi:10.1096/fj.201700221RR. PMID 28842432.

- Sasaki, Y.; Araki, T.; Milbrandt, J. (16 August 2006). "Stimulation of Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Biosynthetic Pathways Delays Axonal Degeneration after Axotomy". Journal of Neuroscience. 26 (33): 8484–8491. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2320-06.2006. PMID 16914673.

- Frederick, David W.; Loro, Emanuele; Liu, Ling; Davila, Antonio; Chellappa, Karthikeyani; Silverman, Ian M.; Quinn, William J.; Gosai, Sager J.; Tichy, Elisia D.; Davis, James G.; Mourkioti, Foteini; Gregory, Brian D.; Dellinger, Ryan W.; Redpath, Philip; Migaud, Marie E.; Nakamaru-Ogiso, Eiko; Rabinowitz, Joshua D.; Khurana, Tejvir S.; Baur, Joseph A. (August 2016). "Loss of NAD Homeostasis Leads to Progressive and Reversible Degeneration of Skeletal Muscle". Cell Metabolism. 24 (2): 269–282. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2016.07.005. PMC 4985182. PMID 27508874.

- Cantó, Carles; Jiang, Lake Q.; Deshmukh, Atul S.; Mataki, Chikage; Coste, Agnes; Lagouge, Marie; Zierath, Juleen R.; Auwerx, Johan (March 2010). "Interdependence of AMPK and SIRT1 for Metabolic Adaptation to Fasting and Exercise in Skeletal Muscle". Cell Metabolism. 11 (3): 213–219. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2010.02.006. PMC 3616265. PMID 20197054.

- Rappou, Elisabeth; Jukarainen, Sakari; Rinnankoski-Tuikka, Rita; Kaye, Sanna; Heinonen, Sini; Hakkarainen, Antti; Lundbom, Jesper; Lundbom, Nina; Saunavaara, Virva; Rissanen, Aila; Virtanen, Kirsi A.; Pirinen, Eija; Pietiläinen, Kirsi H. (March 2016). "Weight Loss Is Associated With Increased NAD /SIRT1 Expression But Reduced PARP Activity in White Adipose Tissue". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 101 (3): 1263–1273. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-3054. PMID 26760174.

- Cantó, Carles; Houtkooper, Riekelt H.; Pirinen, Eija; Youn, Dou Y.; Oosterveer, Maaike H.; Cen, Yana; Fernandez-Marcos, Pablo J.; Yamamoto, Hiroyasu; Andreux, Pénélope A.; Cettour-Rose, Philippe; Gademann, Karl; Rinsch, Chris; Schoonjans, Kristina; Sauve, Anthony A.; Auwerx, Johan (June 2012). "The NAD+ Precursor Nicotinamide Riboside Enhances Oxidative Metabolism and Protects against High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity". Cell Metabolism. 15 (6): 838–847. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2012.04.022. PMC 3616313. PMID 22682224.

- Airhart, Sophia E.; Shireman, Laura M.; Risler, Linda J.; Anderson, Gail D.; Nagana Gowda, G. A.; Raftery, Daniel; Tian, Rong; Shen, Danny D.; O’Brien, Kevin D.; Sinclair, David A. (6 December 2017). "An open-label, non-randomized study of the pharmacokinetics of the nutritional supplement nicotinamide riboside (NR) and its effects on blood NAD+ levels in healthy volunteers". PLOS ONE. 12 (12): e0186459. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186459. PMC 5718430. PMID 29211728.

- Dollerup, Ole L; Christensen, Britt; Svart, Mads; Schmidt, Mark S; Sulek, Karolina; Ringgaard, Steffen; Stødkilde-Jørgensen, Hans; Møller, Niels; Brenner, Charles; Treebak, Jonas T; Jessen, Niels (August 2018). "A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of nicotinamide riboside in obese men: safety, insulin-sensitivity, and lipid-mobilizing effects". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 108 (2): 343–353. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqy132. PMID 29992272.

- Martens, Christopher R.; Denman, Blair A.; Mazzo, Melissa R.; Armstrong, Michael L.; Reisdorph, Nichole; McQueen, Matthew B.; Chonchol, Michel; Seals, Douglas R. (29 March 2018). "Chronic nicotinamide riboside supplementation is well-tolerated and elevates NAD+ in healthy middle-aged and older adults". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 1286. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03421-7. PMC 5876407. PMID 29599478.

- Brenner, Charles (20 April 2006). "Nicotinamide riboside kinase compositions and methods for using the same". Google Patents. Dartmouth College. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- "ChromaDex Licenses Exclusive Patent Rights for Nicotinamide Riboside (NR) Vitamin Technologies". 2012-07-16. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Melody M. Bomgardner (2018). "Firms feud over purported age-fighting molecule". Chemical & Engineering News. 96 (33).

- Dellinger, Ryan W.; Santos, Santiago Roel; Morris, Mark; Evans, Mal; Alminana, Dan; Guarente, Leonard; Marcotulli, Eric (24 November 2017). "Repeat dose NRPT (nicotinamide riboside and pterostilbene) increases NAD+ levels in humans safely and sustainably: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study". NPJ Aging and Mechanisms of Disease. 3 (1): 17. doi:10.1038/s41514-017-0016-9. PMC 5701244. PMID 29184669.

Further reading

- "Press Release: NIH researchers find potential target for reducing obesity-related inflammation". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 16 November 2015.

- Stipp, David (March 11, 2015). "Guest Blog: Beyond Resveratrol: The Anti-Aging NAD Fad". Scientific American Blog Network.

- Zhang, H; Ryu, D; Wu, Y; Gariani, K; Wang, X; Luan, P; D'Amico, D; Ropelle, ER; Lutolf, MP; Aebersold, R; Schoonjans, K; Menzies, KJ; Auwerx, J (17 June 2016). "NAD⁺ repletion improves mitochondrial and stem cell function and enhances life span in mice". Science. 352 (6292): 1436–43. doi:10.1126/science.aaf2693. PMID 27127236.

- Dolopikou CF, Kourtzidis IA, Margaritelis NV, Vrabas IS, Koidou I, Kyparos A, Theodorou AA, Paschalis V, Nikolaidis MG. (2019 Feb 6). Acute nicotinamide riboside supplementation improves redox homeostasis and exercise performance in old individuals: a double-blind cross-over study. doi:10.1007/s00394-019-01919-4.