Multiple sclerosis signs and symptoms

Multiple sclerosis can cause a variety of symptoms: changes in sensation (hypoesthesia), muscle weakness, abnormal muscle spasms, or difficulty moving; difficulties with coordination and balance; problems in speech (dysarthria) or swallowing (dysphagia), visual problems (nystagmus, optic neuritis, phosphenes or diplopia), fatigue and acute or chronic pain syndromes, bladder and bowel difficulties, cognitive impairment, or emotional symptomatology (mainly major depression). The main clinical measure in progression of the disability and severity of the symptoms is the Expanded Disability Status Scale or EDSS.[1]

The initial attacks are often transient, mild (or asymptomatic), and self-limited. They often do not prompt a health care visit and sometimes are only identified in retrospect once the diagnosis has been made after further attacks. The most common initial symptoms reported are: changes in sensation in the arms, legs or face (33%), complete or partial vision loss (optic neuritis) (20%), weakness (13%), double vision (7%), unsteadiness when walking (5%), and balance problems (3%); but many rare initial symptoms have been reported such as aphasia or psychosis.[2][3] Fifteen percent of individuals have multiple symptoms when they first seek medical attention.[4]

Bladder and bowel

Bladder problems (See also urinary system and urination) appear in 70–80% of people with multiple sclerosis (MS) and they have an important effect both on hygiene habits and social activity.[5][6] Bladder problems are usually related with high levels of disability and pyramidal signs in lower limbs.[7]

The most common problems are an increase in frequency and urgency (incontinence) but difficulties to begin urination, hesitation, leaking, sensation of incomplete urination, and retention also appear. When retention occurs secondary urinary infections are common.

There are many cortical and subcortical structures implicated in urination[8] and MS lesions in various central nervous system structures can cause these kinds of symptoms.

Treatment objectives are the alleviation of symptoms of urinary dysfunction, treatment of urinary infections, reduction of complicating factors and the preservation of renal function. Treatments can be classified in two main subtypes: pharmacological and non-pharmacological. Pharmacological treatments vary greatly depending on the origin or type of dysfunction and some examples of the medications used are:[9] alfuzosin for retention,[10] trospium and flavoxate for urgency and incontinency,[11][12] and desmopressin for nocturia.[13][14] Non pharmacological treatments involve the use of pelvic floor muscle training, stimulation, biofeedback, pessaries, bladder retraining, and sometimes intermittent catheterization.[15][16]

Bowel problems affect around 70% of patients, with around 50% of patients suffering from constipation and up to 30% from fecal incontinence.[16] Cause of bowel impairments in MS patients is usually either a reduced gut motility or an impairment in neurological control of defecation. The former is commonly related to immobility or secondary effects from drugs used in the treatment of the disease.[16] Pain or problems with defecation can be helped with a diet change which includes among other changes an increased fluid intake, oral laxatives or suppositories and enemas when habit changes and oral measures are not enough to control the problems.[16][17]

Cognitive

Some of the most common deficits affect recent memory, attention, processing speed, visual-spatial abilities and executive function.[18] Symptoms related to cognition include emotional instability and fatigue including neurological fatigue. Commonly a form of cognitive disarray is experienced, where specific cognitive processes may remain unaffected, but cognitive processes as a whole are impaired. Cognitive deficits are independent of physical disability and can occur in the absence of neurological dysfunction.[19] Severe impairment is a major predictor of a low quality of life, unemployment, caregiver distress,[20] and difficulty in driving;[21] limitations in a patient's social and work activities are also correlated with the extent of impairment.[19]

Cognitive impairments occur in about 40 to 60 percent of patients with multiple sclerosis,[22] with the lowest percentages usually from community-based studies and the highest ones from hospital-based. Impairments may be present at the beginning of the disease.[23] Probable multiple sclerosis sufferers, meaning after a first attack but before a secondary confirmatory one, have up to 50 percent of patients with impairment at onset.[24] Dementia is rare and occurs in only five percent of patients.[19]

Measures of tissue atrophy are well correlated with, and predict, cognitive dysfunction. Neuropsychological outcomes are highly correlated with linear measures of sub-cortical atrophy. Cognitive impairment is the result of not only tissue damage, but tissue repair and adaptive functional reorganization.[20] Neuropsychological testing is important for determining the extent of cognitive deficits. Neuropsychological rehabilitation may help to reverse or decrease the cognitive deficits although studies on the issue have been of low quality.[25] Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are commonly used to treat Alzheimer's disease related dementia and so are thought to have potential in treating the cognitive deficits in multiple sclerosis. They have been found to be effective in preliminary clinical trials.[25]

Emotional

Emotional symptoms are also common and are thought to be both a normal response to having a debilitating disease and the result of damage to specific areas of the central nervous system that generate and control emotions.

Clinical depression is the most common neuropsychiatric condition: lifetime depression prevalence rates of 40–50% and 12-month prevalence rates around 20% have been typically reported for samples of people with MS; these figures are considerably higher than those for the general population or for people with other chronic illnesses.[26][27] Brain imaging studies trying to relate depression to lesions in certain regions of the brain have met with variable success. On balance the evidence seems to favour an association with neuropathology in the left anterior temporal/parietal regions.[28]

Other feelings such as anger, anxiety, frustration, and hopelessness also appear frequently and suicide is a very real threat since it results in 15% of deaths in MS sufferers.[29]

Fatigue

Fatigue is very common and disabling in MS with a close relationship to depressive symptomatology.[31] When depression is reduced fatigue also tends to reduce and it is recommended that patients should be evaluated for depression before other therapeutic approaches are used.[32] In a similar way other factors such as disturbed sleep, chronic pain, poor nutrition, or even some medications can all contribute to fatigue and medical professionals are encouraged to identify and modify them.[33] There are also different medications used to treat fatigue; such as amantadine,[34][35] or pemoline;[36][37] as well as psychological interventions of energy conservation;[38][39] but their effects are small and for these reasons fatigue is a difficult symptom to manage. Fatigue has also been related to specific brain areas in MS using magnetic resonance imaging.[40]

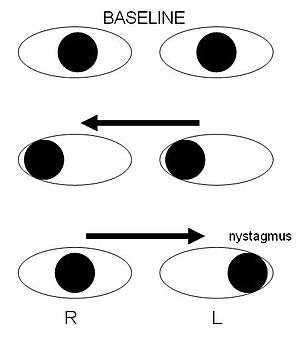

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia is a disorder of conjugate lateral gaze. The affected eye shows impairment of adduction. The partner eye diverges from the affected eye during abduction, producing diplopia; during extreme abduction, compensatory nystagmus can be seen in the partner eye. Diplopia means double vision while nystagmus is involuntary eye movement characterized by alternating smooth pursuit in one direction and a saccadic movement in the other direction.

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia occurs when MS affects a part of the brain stem called the medial longitudinal fasciculus, which is responsible for communication between the two eyes by connecting the abducens nucleus of one side to the oculomotor nucleus of the opposite side. This results in the failure of the medial rectus muscle to contract appropriately, so that the eyes do not move equally (called disconjugate gaze).

Different drugs as well as optic compensatory systems and prisms can be used to improve these symptoms.[41][42][43][44] Surgery can also be used in some cases for this problem.[45]

Mobility restrictions

_Animation_all_rows.gif)

Restrictions in mobility (walking, transfers, bed mobility etc.) are common in individuals suffering from multiple sclerosis. Within 10 years after the onset of MS one-third of patients reach a score of 6 on the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), requiring the use of a unilateral walking aid, and by 30 years the proportion increases to 83%. Within five years of onset the EDSS is six in 50% of those with the progressive form of MS.[46]

A wide range of impairments may exist in MS sufferers which can act either alone or in combination to impact directly on a person's balance, function and mobility. Such impairments include fatigue, weakness, hypertonicity, low exercise tolerance, impaired balance, ataxia and tremor.[47]

Interventions may be aimed at the individual impairments that reduce mobility or at the level of disability. This second level intervention includes provision, education, and instruction in the use of equipment such as walking aids, wheelchairs, motorized scooters and car adaptations as well as instruction on compensatory strategies to accomplish an activity — for example undertaking safe transfers by pivoting in a flexed posture rather than standing up and stepping around.

Optic neuritis

Up to 50% of patients with MS will develop an episode of optic neuritis and 20% of the time optic neuritis is the presenting sign of MS. The presence of demyelinating white matter lesions on brain MRIs at the time of presentation for optic neuritis is the strongest predictor in developing clinical diagnosis of MS. Almost half of patients with optic neuritis have white matter lesions consistent with multiple sclerosis.

At five year follow-ups the overall risk of developing MS is 30%, with or without MRI lesions. Patients with a normal MRI still develop MS (16%), but at a lower rate compared to those patients with three or more MRI lesions (51%). From the other perspective, however, 44% of patients with any demyelinating lesions on MRI at presentation will not have developed MS ten years later.[48][49]

Individuals experience rapid onset of pain in one eye followed by blurry vision in part or all its visual field. Flashes of light (phosphenes) may also be present.[50] Inflammation of the optic nerve causes loss of vision most usually by the swelling and destruction of the myelin sheath covering the optic nerve.

The blurred vision usually resolves within 10 weeks but individuals are often left with less vivid color vision, especially red, in the affected eye.

A systemic intravenous treatment with corticosteroids may quicken the healing of the optic nerve, prevent complete loss of vision and delay the onset of other symptoms.

Pain

Pain is a common symptom in MS. A recent study systematically pooling results from 28 studies (7101 patients) estimates that pain affects 63% of people with MS.[51] These 28 studies described pain in a large range of different people with MS. The authors found no evidence that pain was more common in people with progressive types of MS, in females compared to males, in people with different levels of disability, or in people who had had MS for different periods of time.

Pain can be severe and debilitating, and can have a profound effect on the quality of life and mental health of the sufferer.[52] Certain types of pain are thought to sometimes appear after a lesion to the ascending or descending tracts that control the transmission of painful stimulus, such as the anterolateral system, but many other causes are also possible.[43] The most prevalent types of pain are thought to be headaches (43%), dysesthetic limb pain (26%), back pain (20%), painful spasms (15%), painful Lhermitte's phenomenon (16%) and Trigeminal Neuralgia (3%).[51] These authors did not however find enough data to quantify the prevalence of painful optic neuritis.

Acute pain is mainly due to optic neuritis, trigeminal neuralgia, Lhermitte's sign or dysesthesias.[53] Subacute pain is usually secondary to the disease and can be a consequence of spending too much time in the same position, urinary retention, or infected skin ulcers. Chronic pain is common and harder to treat.

Trigeminal neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia (or "tic douloureux") is a disorder of the trigeminal nerve that causes episodes of intense pain in the eyes, lips, nose, scalp, forehead, and jaw, affecting 2-4% of MS patients.[51] The episodes of pain occur paroxysmally (suddenly) and the patients describe it as trigger area on the face, so sensitive that touching or even air currents can bring an episode of pain. Usually it is successfully treated with anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine,[54] or phenytoin[55] although others such as gabapentin[56] can be used.[57] When drugs are not effective, surgery may be recommended. Glycerol rhizotomy (surgical injection of glycerol into a nerve) has been studied[58] although the beneficial effects and risks in MS patients of the procedures that relieve pressure on the nerve are still under discussion.[59][60]

Lhermitte's sign

Lhermitte's sign is an electrical sensation that runs down the back and into the limbs and is produced by bending the neck forward. The sign suggests a lesion of the dorsal columns of the cervical cord or of the caudal medulla, correlating significantly with cervical MRI abnormalities.[61] Between 25 and 40% of MS patients report having Lhermitte's sign during the course of their illness.[62][63][64] It is not always experienced as painful, but about 16% of people with MS will experience painful Lhermitte's sign.[51]

Dysesthesias

Dysesthesias are disagreeable sensations produced by ordinary stimuli. The abnormal sensations are caused by lesions of the peripheral or central sensory pathways, and are described as painful feelings such as burning, wetness, itching, electric shock or pins and needles. Both Lhermitte's sign and painful dysesthesias usually respond well to treatment with carbamazepine, clonazepam or amitriptyline.[65][66][67] A related symptom is a pleasant, yet unsettling sensation which has no normal explanation (such as sensation of gentle warmth arising from touch by clothing)

Sexual

Sexual dysfunction (SD) is one of many symptoms affecting persons with a diagnosis of MS. SD in men encompasses both erectile and ejaculatory disorder. The prevalence of SD in men with MS ranges from 75 to 91%.[68] Erectile dysfunction appears to be the most common form of SD documented in MS. SD may be due to alteration of the ejaculatory reflex which can be affected by neurological conditions such as MS.[69] Sexual dysfunction is also prevalent in female MS patients, typically lack of orgasm, probably related to disordered genital sensation.

Spasticity

.jpg)

Spasticity is characterised by increased stiffness and slowness in limb movement, the development of certain postures, an association with weakness of voluntary muscle power, and with involuntary and sometimes painful spasms of limbs.[33] Painful spasms affect about 15% of people with MS overall.[51] A physiotherapist can help to reduce spasticity and avoid the development of contractures with techniques such as passive stretching.[70] There is evidence, albeit limited, of the clinical effectiveness of THC and CBD extracts,[71] baclofen,[72] dantrolene,[73] diazepam,[74] and tizanidine.[75][76][77] In the most complicated cases intrathecal injections of baclofen can be used.[78] There are also palliative measures like castings, splints or customised seatings.[33]

Speech

Speech problems include slurred speech, low tone of voice (dysphonia), decreased talking speed, and problems with articulation of sounds (dysarthria). A related problem, since it involves similar anatomical structures, is swallowing difficulties (dysphagia).[79]

Transverse myelitis

Some MS patients develop rapid onset of numbness, weakness, bowel or bladder dysfunction, and/or loss of muscle function, typically in the lower half of the body. This is the result of MS attacking the spinal cord. The symptoms and signs depend upon the nerve cords involved and the extent of the involvement.

Prognosis for complete recovery is generally poor. Recovery from transverse myelitis usually begins between weeks 2 and 12 following onset and may continue for up to 2 years in some patients and as many as 80% of individuals with transverse myelitis are left with lasting disabilities.

Though it was considered for many years that traverse myelitis was a normal consequence of MS, since the discovery of anti-AQP4 and anti-MOG biomarkers it is not. Now TM is considered an indicator of neuromyelitis optica, and a red flag against the diagnosis of MS.[80]

Tremor and ataxia

Tremor is an unintentional, somewhat rhythmic, muscle movement involving to-and-fro movements (oscillations) of one or more parts of the body. It is the most common of all involuntary movements and can affect the hands, arms, head, face, vocal cords, trunk, and legs. Ataxia is an unsteady and clumsy motion of the limbs or torso due to a failure of the gross coordination of muscle movements. People with ataxia experience a failure of muscle control in their arms and legs, resulting in a lack of balance and coordination or a disturbance of gait.

Tremor and ataxia are frequent in MS and present in 25 to 60% of patients. They can be very disabling and embarrassing, and are difficult to manage.[81] The origin of tremor in MS is difficult to identify but it can be due to a mixture of different factors such as damage to the cerebellar connections, weakness, spasticity, etc.

Many medications have been proposed to treat tremor; however their efficacy is very limited. Medications that have been reported to provide some relief are isoniazid,[82][83][84][85] carbamazepine,[54] propranolol[86][87][88] and gluthetimide[89] but published evidence of effectiveness is limited.[90] Physical therapy is not indicated as a treatment for tremor or ataxia although the use of orthese devices can help. An example is the use of wrist bandages with weights, which can be useful to increase the inertia of movement and therefore reduce tremor.[91] Daily use objects are also adapted so they are easier to grab and use.

If all these measures fail patients are candidates for thalamus surgery. This kind of surgery can be both a thalamotomy or the implantation of a thalamic stimulator. Complications are frequent (30% in thalamotomy and 10% in deep brain stimulation) and include a worsening of ataxia, dysarthria and hemiparesis. Thalamotomy is a more efficacious surgical treatment for intractable MS tremor though the higher incidence of persistent neurological deficits in patients receiving lesional surgery supports the use of deep brain stimulation as the preferred surgical strategy.[92]

References

- Kurtzke JF (1983). "Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS)". Neurology. 33 (11): 1444–52. doi:10.1212/WNL.33.11.1444. PMID 6685237.

- Navarro S, Mondéjar-Marín B, Pedrosa-Guerrero A, Pérez-Molina I, Garrido-Robres J, Alvarez-Tejerina A (2005). "[Aphasia and parietal syndrome as the presenting symptoms of a demyelinating disease with pseudotumoral lesions]". Rev Neurol. 41 (10): 601–3. PMID 16288423.

- Jongen P (2006). "Psychiatric onset of multiple sclerosis". J Neurol Sci. 245 (1–2): 59–62. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2005.09.014. PMID 16631798.

- Paty D, Studney D, Redekop K, Lublin F (1994). "MS COSTAR: a computerized patient record adapted for clinical research purposes". Annals of Neurology. 36 Suppl: S134–5. doi:10.1002/ana.410360732. PMID 8017875.

- Hennessey A, Robertson NP, Swingler R, Compston DA (1999). "Urinary, faecal and sexual dysfunction in patients with multiple sclerosis". J. Neurol. 246 (11): 1027–32. doi:10.1007/s004150050508. PMID 10631634.

- Burguera-Hernández JA (2000). "[Urinary alterations in multiple sclerosis]". Revista de Neurologia (in Spanish). 30 (10): 989–92. doi:10.33588/rn.3010.99371. PMID 10919202.

- Betts CD, D'Mellow MT, Fowler CJ (1993). "Urinary symptoms and the neurological features of bladder dysfunction in multiple sclerosis". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 56 (3): 245–50. doi:10.1136/jnnp.56.3.245. PMC 1014855. PMID 8459239.

- Nour S, Svarer C, Kristensen JK, Paulson OB, Law I (2000). "Cerebral activation during micturition in normal men". Brain. 123 (4): 781–9. doi:10.1093/brain/123.4.781. PMID 10734009.

- Ayuso-Peralta L, de Andrés C (2002). "[Symptomatic treatment of multiple sclerosis]". Revista de Neurologia (in Spanish). 35 (12): 1141–53. PMID 12497297.

- Information from the USA National library of medicine on alfuzosin

- Information from the USA National library of medicine on trospium

- Information from the USA National library of medicine on flavoxate

- Bosma R, Wynia K, Havlíková E, De Keyser J, Middel B (2005). "Efficacy of desmopressin in patients with multiple sclerosis suffering from bladder dysfunction: a meta-analysis" (PDF). Acta Neurol. Scand. 112 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2005.00431.x. PMID 15932348.

- Information from the USA National library of medicine on desmopressin

- Frances M Diro (2006) "Urological Management in Neurological Disease"

- The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions (UK) (2004). "Diagnosis and treatment of specific impairments". Multiple sclerosis: national clinical guideline for diagnosis and management in primary and secondary care. NICE Clinical Guidelines. 8. London: Royal College of Physicians (UK). pp. 87–132. ISBN 978-1-86016-182-7. PMID 21290636. Retrieved 6 February 2013. External link in

|title=(help) - DasGupta R, Fowler CJ (2003). "Bladder, bowel and sexual dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: management strategies". Drugs. 63 (2): 153–66. doi:10.2165/00003495-200363020-00003. PMID 12515563.

- Bobholz J, Rao S (2003). "Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: a review of recent developments". Current Opinion in Neurology. 16 (3): 283–8. doi:10.1097/00019052-200306000-00006. PMID 12858063.

- Amato MP, Ponziani G, Siracusa G, Sorbi S (October 2001). "Cognitive dysfunction in early-onset multiple sclerosis: a reappraisal after 10 years". Arch. Neurol. 58 (10): 1602–6. doi:10.1001/archneur.58.10.1602. PMID 11594918.

- Benedict RH, Carone DA, Bakshi R (July 2004). "Correlating brain atrophy with cognitive dysfunction, mood disturbances, and personality disorder in multiple sclerosis". J Neuroimaging. 14 (3 Suppl): 36S–45S. doi:10.1177/1051228404266267. PMID 15228758.

- Shawaryn M, Schultheis M, Garay E, Deluca J (2002). "Assessing functional status: exploring the relationship between the multiple sclerosis functional composite and driving". Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 83 (8): 1123–9. doi:10.1053/apmr.2002.33730. PMID 12161835.

- Rao S, Leo G, Bernardin L, Unverzagt F (1991). "Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. I. Frequency, patterns, and prediction". Neurology. 41 (5): 685–91. doi:10.1212/wnl.41.5.685. PMID 2027484.

- Dujardin, K.; Donze, AC; Hautecoeur, P (1998). "Attention impairment in recently diagnosed multiple sclerosis". Eur J Neurol. 5 (1): 61–66. doi:10.1046/j.1468-1331.1998.510061.x. PMID 10210813.

- Achiron A, Barak Y (2003). "Cognitive impairment in probable multiple sclerosis". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 74 (4): 443–6. doi:10.1136/jnnp.74.4.443. PMC 1738365. PMID 12640060.

- Chiaravalloti ND, DeLuca J (Dec 2008). "Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis". Lancet Neurol. 7 (12): 1139–51. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70259-X. PMID 19007738.

- Sadovnick A, Remick R, Allen J, Swartz E, Yee I, Eisen K, Farquhar R, Hashimoto S, Hooge J, Kastrukoff L, Morrison W, Nelson J, Oger J, Paty D (1996). "Depression and multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 46 (3): 628–32. doi:10.1212/wnl.46.3.628. PMID 8618657.

- Patten S, Beck C, Williams J, Barbui C, Metz L (2003). "Major depression in multiple sclerosis: a population-based perspective". Neurology. 61 (11): 1524–7. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.581.3646. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000095964.34294.b4. PMID 14663036.

- Siegert R, Abernethy D (2005). "Depression in multiple sclerosis: a review". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 76 (4): 469–75. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2004.054635. PMC 1739575. PMID 15774430.

- Sadovnick A, Eisen K, Ebers G, Paty D (1991). "Cause of death in patients attending multiple sclerosis clinics". Neurology. 41 (8): 1193–6. doi:10.1212/wnl.41.8.1193. PMID 1866003.

- Murray ED, Buttner N, Price BH. (2012) Depression and Psychosis in Neurological Practice. In: Neurology in Clinical Practice, 6th Edition. Bradley WG, Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, Jankovic J (eds.) Butterworth Heinemann. April 12, 2012. ISBN 1437704344 | ISBN 978-1437704341

- Bakshi R (2003). "Fatigue associated with multiple sclerosis: diagnosis, impact and management". Mult. Scler. 9 (3): 219–27. doi:10.1191/1352458503ms904oa. PMID 12814166.

- Mohr DC, Hart SL, Goldberg A (2003). "Effects of treatment for depression on fatigue in multiple sclerosis". Psychosomatic Medicine. 65 (4): 542–7. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.318.5928. doi:10.1097/01.PSY.0000074757.11682.96. PMID 12883103.

- The Royal College of Physicians (2004). Multiple Sclerosis. National clinical guideline for diagnosis and management in primary and secondary care. Salisbury, Wiltshire: Sarum ColourView Group. ISBN 978-1-86016-182-7.Free full text (2004-08-13). Retrieved on 2007-10-01.

- Pucci E, Branãs P, D'Amico R, Giuliani G, Solari A, Taus C (2007). Pucci E (ed.). "Amantadine for fatigue in multiple sclerosis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD002818. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002818.pub2. PMID 17253480.

- Amantadine. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-07.

- Weinshenker BG, Penman M, Bass B, Ebers GC, Rice GP (1992). "A double-blind, randomized, crossover trial of pemoline in fatigue associated with multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 42 (8): 1468–71. doi:10.1212/wnl.42.8.1468. PMID 1641137.

- Pemoline. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2006-01-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-07.

- Mathiowetz VG, Finlayson ML, Matuska KM, Chen HY, Luo P (2005). "Randomized controlled trial of an energy conservation course for persons with multiple sclerosis". Mult. Scler. 11 (5): 592–601. doi:10.1191/1352458505ms1198oa. PMID 16193899.

- Matuska K, Mathiowetz V, Finlayson M (2007). "Use and perceived effectiveness of energy conservation strategies for managing multiple sclerosis fatigue". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 61 (1): 62–9. doi:10.5014/ajot.61.1.62. PMID 17302106.

- Sepulcre J, Masdeu J, Goñi J, et al. (November 2008). "Fatigue in multiple sclerosis is associated with the disruption of frontal and parietal pathways". Mult. Scler. 15 (3): 337–44. doi:10.1177/1352458508098373. PMID 18987107.

- Leigh RJ, Averbuch-Heller L, Tomsak RL, Remler BF, Yaniglos SS, Dell'Osso LF (1994). "Treatment of abnormal eye movements that impair vision: strategies based on current concepts of physiology and pharmacology". Annals of Neurology. 36 (2): 129–41. doi:10.1002/ana.410360204. PMID 8053648.

- Starck M, Albrecht H, Pöllmann W, Straube A, Dieterich M (1997). "Drug therapy for acquired pendular nystagmus in multiple sclerosis". J. Neurol. 244 (1): 9–16. doi:10.1007/PL00007728. PMID 9007739.

- Clanet MG, Brassat D (2000). "The management of multiple sclerosis patients". Current Opinion in Neurology. 13 (3): 263–70. doi:10.1097/00019052-200006000-00005. PMID 10871249.

- Menon GJ, Thaller VT (2002). "Therapeutic external ophthalmoplegia with bilateral retrobulbar botulinum toxin- an effective treatment for acquired nystagmus with oscillopsia". Eye (London, England). 16 (6): 804–6. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6700167. PMID 12439689.

- Jain S, Proudlock F, Constantinescu CS, Gottlob I (2002). "Combined pharmacologic and surgical approach to acquired nystagmus due to multiple sclerosis". Am. J. Ophthalmol. 134 (5): 780–2. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(02)01629-X. PMID 12429265.

- Weinshenker BG, Bass B, Rice GP, et al. (1989). "The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study. I. Clinical course and disability". Brain. 112 (1): 133–46. doi:10.1093/brain/112.1.133. PMID 2917275.

- Freeman JA (2001). "Improving mobility and functional independence in persons with multiple sclerosis". J. Neurol. 248 (4): 255–9. doi:10.1007/s004150170198. PMID 11374088.

- Beck RW, Trobe JD (1995). "What we have learned from the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial". Ophthalmology. 102 (10): 1504–8. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30839-1. PMID 9097798.

- "The 5-year risk of MS after optic neuritis: experience of the optic neuritis treatment trial. 1997". Neurology. 57 (12 Suppl 5): S36–45. 2001. PMID 11902594.

- Cervetto L, Demontis GC, Gargini C (February 2007). "Cellular mechanisms underlying the pharmacological induction of phosphenes". Br. J. Pharmacol. 150 (4): 383–90. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706998. PMC 2189731. PMID 17211458.

- Foley P, Vesterinen H, Laird B, et al. (2013). "Prevalence and natural history of pain in adults with multiple sclerosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis". Pain. 154 (5): 632–42. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2012.12.002. PMID 23318126.

- Archibald CJ, McGrath PJ, Ritvo PG, et al. (1994). "Pain prevalence, severity and impact in a clinic sample of multiple sclerosis patients". Pain. 58 (1): 89–93. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(94)90188-0. PMID 7970843.

- Kerns RD, Kassirer M, Otis J (2002). "Pain in multiple sclerosis: a biopsychosocial perspective". Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 39 (2): 225–32. PMID 12051466.

- Information from the USA National library of medicine on carbamazepine

- Information from the USA National library of medicine on phenytoin

- Information from the USA National library of medicine on gabapentin

- Solaro C, Messmer Uccelli M, Uccelli A, Leandri M, Mancardi GL (2000). "Low-dose gabapentin combined with either lamotrigine or carbamazepine can be useful therapies for trigeminal neuralgia in multiple sclerosis". Eur. Neurol. 44 (1): 45–8. doi:10.1159/000008192. PMID 10894995.

- Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD, Bissonette DJ (1994). "Long-term results after glycerol rhizotomy for multiple sclerosis-related trigeminal neuralgia". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 21 (2): 137–40. doi:10.1017/S0317167100049076. PMID 8087740.

- Athanasiou TC, Patel NK, Renowden SA, Coakham HB (2005). "Some patients with multiple sclerosis have neurovascular compression causing their trigeminal neuralgia and can be treated effectively with MVD: report of five cases". British Journal of Neurosurgery. 19 (6): 463–8. doi:10.1080/02688690500495067. PMID 16574557.

- Eldridge PR, Sinha AK, Javadpour M, Littlechild P, Varma TR (2003). "Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia in patients with multiple sclerosis". Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery. 81 (1–4): 57–64. doi:10.1159/000075105. PMID 14742965.

- Gutrecht JA, Zamani AA, Slagado ED (1993). "Anatomic-radiologic basis of Lhermitte's sign in multiple sclerosis". Arch. Neurol. 50 (8): 849–51. doi:10.1001/archneur.1993.00540080056014. PMID 8352672.

- Al-Araji AH, Oger J (2005). "Reappraisal of Lhermitte's sign in multiple sclerosis". Mult. Scler. 11 (4): 398–402. doi:10.1191/1352458505ms1177oa. PMID 16042221.

- Sandyk R, Dann LC (1995). "Resolution of Lhermitte's sign in multiple sclerosis by treatment with weak electromagnetic fields". Int. J. Neurosci. 81 (3–4): 215–24. doi:10.3109/00207459509004888. PMID 7628912.

- Kanchandani R, Howe JG (1982). "Lhermitte's sign in multiple sclerosis: a clinical survey and review of the literature". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 45 (4): 308–12. doi:10.1136/jnnp.45.4.308. PMC 491365. PMID 7077340.

- Information from the USA National library of medicine on clonazepam

- Information from the USA National library of medicine on amitriptyline

- Moulin DE, Foley KM, Ebers GC (1988). "Pain syndromes in multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 38 (12): 1830–4. doi:10.1212/wnl.38.12.1830. PMID 2973568.

- O'Leary et al., 2007

- O'Leary, M., Heyman, R., Erickson, J., Chancellor, M.B.: Premature ejaculation and MS: A Review, Consortium of MS Centers, http://www.mscare.org, June 2007

- Cardini RG, Crippa AC, Cattaneo D (2000). "Update on multiple sclerosis rehabilitation". J. Neurovirol. 6 Suppl 2: S179–85. PMID 10871810.

- Lakhan SE, Rowland M (2009). "Whole plant cannabis extracts in the treatment of spasticity in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review". BMC Neurology. 9: 59. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-9-59. PMC 2793241. PMID 19961570.

- Baclofen oral. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-17.

- Dantrolene oral. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-17.

- Diazepam. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2005-07-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-17.

- Tizanidine. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2005-07-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-17.

- Beard S, Hunn A, Wight J (2003). "Treatments for spasticity and pain in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review". Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England). 7 (40): iii, ix–x, 1–111. doi:10.3310/hta7400. PMID 14636486.

- Paisley S, Beard S, Hunn A, Wight J (2002). "Clinical effectiveness of oral treatments for spasticity in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review". Mult. Scler. 8 (4): 319–29. doi:10.1191/1352458502ms795rr. PMID 12166503.

- Becker WJ, Harris CJ, Long ML, Ablett DP, Klein GM, DeForge DA (1995). "Long-term intrathecal baclofen therapy in patients with intractable spasticity". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 22 (3): 208–17. doi:10.1017/S031716710003986X. PMID 8529173.

- Richard Senelick (Reviewer) (Aug 2012). "The Speech and Swallowing Problems of Multiple Sclerosis". Web MD. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- Solmaz Asnafi et al., The Frequency of Longitudinally Extensive Transverse Myelitis in MS; A Population-Based Study, October 30, 2019, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2019.101487

- Koch M, Mostert J, Heersema D, De Keyser J (2007). "Tremor in multiple sclerosis". J. Neurol. 254 (2): 133–45. doi:10.1007/s00415-006-0296-7. PMC 1915650. PMID 17318714.

- Bozek CB, Kastrukoff LF, Wright JM, Perry TL, Larsen TA (1987). "A controlled trial of isoniazid therapy for action tremor in multiple sclerosis". J. Neurol. 234 (1): 36–9. doi:10.1007/BF00314007. PMID 3546605.

- Duquette P, Pleines J, du Souich P (1985). "Isoniazid for tremor in multiple sclerosis: a controlled trial". Neurology. 35 (12): 1772–5. doi:10.1212/wnl.35.12.1772. PMID 3906430.

- Hallett M, Lindsey JW, Adelstein BD, Riley PO (1985). "Controlled trial of isoniazid therapy for severe postural cerebellar tremor in multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 35 (9): 1374–7. doi:10.1212/wnl.35.9.1374. PMID 3895037.

- Information from the USA National library of medicine on Isoniazid

- Koller WC (1984). "Pharmacologic trials in the treatment of cerebellar tremor". Arch. Neurol. 41 (3): 280–1. doi:10.1001/archneur.1984.04050150058017. PMID 6365047.

- Sechi GP, Zuddas M, Piredda M, Agnetti V, Sau G, Piras ML, Tanca S, Rosati G (1989). "Treatment of cerebellar tremors with carbamazepine: a controlled trial with long-term follow-up". Neurology. 39 (8): 1113–5. doi:10.1212/wnl.39.8.1113. PMID 2668787.

- Information from the USA National library of medicine on propanolol

- Aisen ML, Holzer M, Rosen M, Dietz M, McDowell F (1991). "Glutethimide treatment of disabling action tremor in patients with multiple sclerosis and traumatic brain injury". Arch. Neurol. 48 (5): 513–5. doi:10.1001/archneur.1991.00530170077023. PMID 2021365.

- Mills RJ, Yap L, Young CA (2007). Mills RJ (ed.). "Treatment for ataxia in multiple sclerosis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD005029. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005029.pub2. PMID 17253537.

- Aisen ML, Arnold A, Baiges I, Maxwell S, Rosen M (1993). "The effect of mechanical damping loads on disabling action tremor". Neurology. 43 (7): 1346–50. doi:10.1212/wnl.43.7.1346. PMID 8327136.

- Bittar RG, Hyam J, Nandi D, Wang S, Liu X, Joint C, Bain PG, Gregory R, Stein J, Aziz TZ (2005). "Thalamotomy versus thalamic stimulation for multiple sclerosis tremor". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 12 (6): 638–42. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2004.09.008. PMID 16098758.