Middle ear

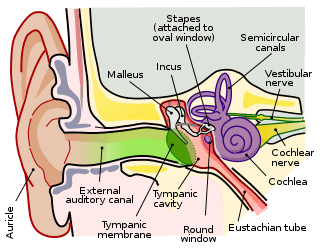

The middle ear is the portion of the ear internal to the eardrum, and external to the oval window of the inner ear. The mammalian middle ear contains three ossicles, which transfer the vibrations of the eardrum into waves in the fluid and membranes of the inner ear. The hollow space of the middle ear is also known as the tympanic cavity and is surrounded by the tympani bone. The auditory tube (also known as the Eustachian tube or the pharyngotympanic tube) joins the tympanic cavity with the nasal cavity (nasopharynx), allowing pressure to equalize between the middle ear and throat.

| Middle ear | |

|---|---|

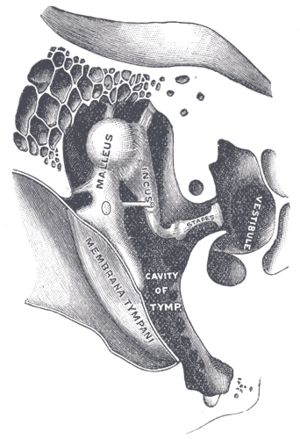

A diagram of the anatomy of the human ear:

| |

| Details | |

| Nerve | glossopharyngeal nerve |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | auris media |

| MeSH | D004432 |

| TA | A15.3.02.001 |

| FMA | 56513 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

|

| This article is one of a series documenting the anatomy of the |

| Human ear |

|---|

|

The primary function of the middle ear is to efficiently transfer acoustic energy from compression waves in air to fluid–membrane waves within the cochlea.

Structure

Ossicles

The middle ear contains three tiny bones known as the ossicles: malleus, incus, and stapes. The ossicles were given their Latin names for their distinctive shapes; they are also referred to as the hammer, anvil, and stirrup, respectively. The ossicles directly couple sound energy from the ear drum to the oval window of the cochlea. While the stapes is present in all tetrapods, the malleus and incus evolved from lower and upper jaw bones present in reptiles.

The ossicles are classically supposed to mechanically convert the vibrations of the eardrum, into amplified pressure waves in the fluid of the cochlea (or inner ear) with a lever arm factor of 1.3. Since the effective vibratory area of the eardrum is about 14 fold larger than that of the oval window, the sound pressure is concentrated, leading to a pressure gain of at least 18.1. The eardrum is merged to the malleus, which connects to the incus, which in turn connects to the stapes. Vibrations of the stapes footplate introduce pressure waves in the inner ear. There is a steadily increasing body of evidence that shows that the lever arm ratio is actually variable, depending on frequency. Between 0.1 and 1 kHz it is approximately 2, it then rises to around 5 at 2 kHz and then falls off steadily above this frequency.[1] The measurement of this lever arm ratio is also somewhat complicated by the fact that the ratio is generally given in relation to the tip of the malleus (also known as the umbo) and the level of the middle of the stapes. The eardrum is actually attached to the malleus handle over about a 0.5 cm distance. In addition the eardrum itself moves in a very chaotic fashion at frequencies >3 kHz. The linear attachment of the eardrum to the malleus actually smooths out this chaotic motion and allows the ear to respond linearly over a wider frequency range than a point attachment. The auditory ossicles can also reduce sound pressure (the inner ear is very sensitive to overstimulation), by uncoupling each other through particular muscles.

The middle ear efficiency peaks at a frequency of around 1 kHz. The combined transfer function of the outer ear and middle ear gives humans a peak sensitivity to frequencies between 1 kHz and 3 kHz.

Muscles

The movement of the ossicles may be stiffened by two muscles. The stapedius muscle, the smallest skeletal muscle in the body, connects to the stapes and is controlled by the facial nerve; the tensor tympani muscle is attached to the upper end of the medial surface of the handle of malleus[2] and is under the control of the medial pterygoid nerve which is a branch of the mandibular nerve of the trigeminal nerve. These muscles contract in response to loud sounds, thereby reducing the transmission of sound to the inner ear. This is called the acoustic reflex.

Nerves

Of surgical importance are two branches of the facial nerve that also pass through the middle ear space. These are the horizontal portion of the facial nerve and the chorda tympani. Damage to the horizontal branch during ear surgery can lead to paralysis of the face (same side of the face as the ear). The chorda tympani is the branch of the facial nerve that carries taste from the ipsilateral half (same side) of the tongue.

Function

Sound transfer

Ordinarily, when sound waves in air strike liquid, most of the energy is reflected off the surface of the liquid. The middle ear allows the impedance matching of sound traveling in air to acoustic waves traveling in a system of fluids and membranes in the inner ear. This system should not be confused, however, with the propagation of sound as compression waves in liquid.

The middle ear couples sound from air to the fluid via the oval window, using the principle of "mechanical advantage" in the form of the "hydraulic principle" and the "lever principle".[3] The vibratory portion of the tympanic membrane (eardrum) is many times the surface area of the footplate of the stapes (the third ossicular bone which attaches to the oval window); furthermore, the shape of the articulated ossicular chain is like a lever, the long arm being the long process of the malleus, the fulcrum being the body of the incus, and the short arm being the lenticular process of the incus. The collected pressure of sound vibration that strikes the tympanic membrane is therefore concentrated down to this much smaller area of the footplate, increasing the force but reducing the velocity and displacement, and thereby coupling the acoustic energy.

The middle ear is able to dampen sound conduction substantially when faced with very loud sound, by noise-induced reflex contraction of the middle-ear muscles.

Clinical significance

The middle ear is hollow. In a high-altitude environment or on diving into water, there will be a pressure difference between the middle ear and the outside environment. This pressure will pose a risk of bursting or otherwise damaging the tympanum if it is not relieved. If middle ear pressure remains low, the ear drum may become retracted into the middle ear <cite>. One of the functions of the Eustachian tubes that connect the middle ear to the nasopharynx is to help keep middle ear pressure the same as air pressure. The Eustachian tubes are normally pinched off at the nose end, to prevent being clogged with mucus, but they may be opened by lowering and protruding the jaw; this is why yawning or chewing helps relieve the pressure felt in the ears when on board an aircraft.

Otitis media is an inflammation of the middle ear.

Other animals

The middle ear of tetrapods is analogous with the spiracle of fishes, an opening from the pharynx to the side of the head in front of the main gill slits. In fish embryos, the spiracle forms as a pouch in the pharynx, which grows outward and breaches the skin to form an opening; in most tetrapods, this breach is never quite completed, and the final vestige of tissue separating it from the outside world becomes the eardrum. The inner part of the spiracle, still connected to the pharynx, forms the eustachian tube.[4]

In reptiles, birds, and early fossil tetrapods, there is a single auditory ossicle, the columella ( that is homologous with the stapes, or "stirrup" of mammals). This is connected indirectly with the eardrum via a mostly cartilaginous extracolumella and medially to the inner-ear spaces via a widened footplate in the fenestra ovalis.[4] The columella is an evolutionary derivative of the bone known as the hyomandibula in fish ancestors, a bone that supported the skull and braincase.

The structure of the middle ear in living amphibians varies considerably, and is often degenerate. In most frogs and toads, it is similar to that of reptiles, but in other amphibians, the middle ear cavity is often absent. In these cases, the stapes either is also missing or, in the absence of an eardrum, connects to the quadrate bone in the skull, although, it is presumed, it still has some ability to transmit vibrations to the inner ear. In many amphibians, there is also a second auditory ossicle, the operculum (not to be confused with the structure of the same name in fishes). This is a flat, plate-like bone, overlying the fenestra ovalis, and connecting it either to the stapes or, via a special muscle, to the scapula. It is not found in any other vertebrates.[4]

Mammals are unique in having evolved a three-ossicle middle-ear independently of the various single-ossicle middle ears of other land vertebrates, all during the Triassic period of geological history. Functionally, the mammalian middle ear is very similar to the single-ossicle ear of non-mammals, except that it responds to sounds of higher frequency, because these are better taken up by the inner ear (which also responds to higher frequencies than those of non-mammals). The malleus, or "hammer", evolved from the articular bone of the lower jaw, and the incus, or "anvil", from the quadrate. In other vertebrates, these bones form the primary jaw joint, but the expansion of the dentary bone in mammals led to the evolution of an entirely new jaw joint, freeing up the old joint to become part of the ear. For a period of time, both jaw joints existed together, one medially and one laterally. The evolutionary process leading to a three-ossicle middle ear was thus an "accidental" byproduct of the simultaneous evolution of the new, secondary jaw joint. In many mammals, the middle ear also becomes protected within a cavity, the auditory bulla, not found in other vertebrates. A bulla evolved late in time and independently numerous times in different mammalian clades, and it can be surrounded by membranes, cartilage or bone. The bulla in humans is part of the temporal bone.[4]

Additional images

See also

- Facial canal

- Hearing

References

- Koike, Takuji; Wada, Hiroshi; Kobayashi, Toshimitsu (2002). "Modeling of the human middle ear using the finite-element method". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 111 (3): 1306–1317. Bibcode:2002ASAJ..111.1306K. doi:10.1121/1.1451073. PMID 11931308.

- Standring, Susan (2015-08-07). Gray's Anatomy E-Book: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780702068515.

- Joseph D. Bronzino (2006). Biomedical Engineering Fundamentals. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-2121-4.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 480–488. ISBN 978-0-03-910284-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Middle ear. |