Meckel's diverticulum

A Meckel's diverticulum, a true congenital diverticulum, is a slight bulge in the small intestine present at birth and a vestigial remnant of the omphalomesenteric duct (also called the vitelline duct or yolk stalk). It is the most common malformation of the gastrointestinal tract and is present in approximately 2% of the population,[1] with males more frequently experiencing symptoms.

| Meckel's diverticulum | |

|---|---|

| |

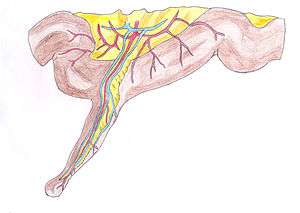

| Schematic drawing of a Meckel's diverticulum with a part of the small intestine. | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Meckel's diverticulum was first explained by Fabricius Hildanus in the sixteenth century and later named after Johann Friedrich Meckel, who described the embryological origin of this type of diverticulum in 1809.[2][3]

Signs and symptoms

The majority of people with a Meckel's diverticulum are asymptomatic. An asymptomatic Meckel's diverticulum is called a silent Meckel's diverticulum.[4] If symptoms do occur, they typically appear before the age of two years.

The most common presenting symptom is painless rectal bleeding such as melaena-like black offensive stools, followed by intestinal obstruction, volvulus and intussusception. Occasionally, Meckel's diverticulitis may present with all the features of acute appendicitis. Also, severe pain in the epigastric region is experienced by the person along with bloating in the epigastric and umbilical regions. At times, the symptoms are so painful that they may cause sleepless nights with acute pain felt in the foregut region, specifically in the epigastric and umbilical regions.

In some cases, bleeding occurs without warning and may stop spontaneously. The symptoms can be extremely painful, often mistaken as just stomach pain resulting from not eating or constipation.

Rarely, a Meckel's diverticulum containing ectopic pancreatic tissue can present with abdominal pain and increased serum amylase levels, mimicking acute pancreatitis.[5]

Complications

The lifetime risk for a person with Meckel's diverticulum to develop certain complications is about 4–6%. Gastrointestinal bleeding, peritonitis or intestinal obstruction may occur in 15–30% of symptomatic people (Table 1). Only 6.4% of all complications requires surgical treatment; and untreated Meckel's diverticulum has a mortality rate of 2.5–15%.[6]

Table 1 – Complications of Meckel's Diverticulum:[7]

| Complications | Percentage of symptomatic Meckel’s Diverticulum (%) |

|---|---|

| Haemorrhage | 20–30 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 20–25 |

| Diverticulitis | 10–20 |

| Umbilical anomalies | ≤10 |

| Neoplasm | 0.5-2 |

Bleeding

Bleeding of the diverticulum is most common in young children, especially in males who are less than 2 years of age.[8] Symptoms may include bright red blood in stools (hematochezia), weakness, abdominal tenderness or pain, and even anaemia in some cases.[9]

Bleeding may be caused by:

- Ectopic gastric or pancreatic mucosa:

- Where diverticulum contains embryonic remnants of mucosa of other tissue types.

- Secretion of gastric acid or alkaline pancreatic juice from the ectopic mucosa leads to ulceration in the adjacent ileal mucosa i.e. peptic or pancreatic ulcer.[10]

- Pain, bleeding or perforation of the bowel at the diverticulum may result.

- Mechanical stimulation may also cause erosion and ulceration.

- Gastrointestinal bleeding may be self-limiting but chronic bleeding may lead to iron deficiency anaemia.[11]

The appearance of stools may indicate the nature of the bleeding:

- Tarry stools: Alteration of blood produced by slow bowel transit due to minor bleeding in upper gastrointestinal tract

- Bright red blood stools: Brisk bleeding

- Stools with blood streak: Anal fissure

- "Currant jelly" stools: Ischaemia of the intestine leads to copious mucus production and may indicate that one part of the bowel invaginates into another intussusception.

Diverticulitis

Inflammation of the diverticulum can mimic symptoms of appendicitis, i.e., periumbilical tenderness and intermittent crampy abdominal pain. Perforation of the inflamed diverticulum can result in peritonitis. Diverticulitis can also cause adhesions, leading to intestinal obstruction.[12]

Diverticulitis may result from:

- Association with the mesodiverticular band attaching to the diverticulum tip where torsion has occurred, causing inflammation and ischaemia.[13]

- Peptic ulceration resulting from ectopic gastric mucosa of the diverticulum

- Following perforation by trauma or ingested foreign material e.g. stalk of vegetable, seeds or fish/chicken bone that become lodged in Meckel's diverticulum.[14]

- Luminal obstruction due to tumors, enterolith, foreign body, causing stasis or bacterial infection.[15]

- Association with acute appendicitis

Intestinal obstruction

Symptoms: Vomiting, abdominal pain and severe or complete constipation.[16]

- The vitelline vessels remnant that connects the diverticulum to the umbilicus may form a fibrous or twisting band (volvulus), trapping the small intestine and causing obstruction. Localised periumbilical pain may be experienced in the right lower quadrant (like appendicitis).[15]

- "Incarceration": when a Meckel's diverticulum is constricted in an inguinal hernia, forming a Littré hernia that obstructs the intestine.[17]

- Chronic diverticulitis causing stricture

- Strangulation of the diverticulum in the obturator foramen.

- Tumors e.g. carcinoma: direct spread of an adenocarcinoma arising in the diverticulum may lead to obstruction

- Lithiasis, stones that are formed in Meckel's diverticulum can:

- Extrude into the terminal ileum, leading to obstruction

- Induce local inflammation and intussusception.[15]

- The diverticulum itself or tumour within it may cause intussusception. For example, from the ileum to the colon, causing obstruction. Symptoms of this include "currant jelly" stools and a palpable lump in the lower abdomen.[7] This occurs when the diverticulum inverts into the lumen of the ileum, due to either:

- An active peristaltic mechanism of the diverticulum that attempts to remove irritating factors

- A passive process such as the transit of food[9]

Umbilical anomalies

Anomalies between the diverticulum and umbilicus may include the presence of fibrous cord, cyst, fistula or sinus, leading to:[12]

- Infection or excoriation of periumbilical skin, resulting in a discharging sinus

- Recurrent infection and healing of sinus

- Abscess formation in the abdominal wall

- Fibrous cord increases the risk of volvulus formation and internal herniation

Neoplasm

Tumors in Meckel's diverticulum may cause bleeding, acute abdominal pain, gastrointestinal obstruction, perforation or intussusception.[12]

- Benign tumors:

- Leiomyoma

- Lipoma

- Vascular and neuromuscular hamartoma

- Carcinoids: most common, 44%

- Mesenchymal tumors: Leiomyosarcoma, peripheral nerve sheath and gastrointestinal stromal tumors, 35%

- Adenocarcinoma, 16%

- Desmoplastic small round cell tumor

Other complications

- A diverticulum inside a Meckel's diverticulum (daughter diverticula)

- Stones and phytobezoar (a bezoar of vegetable fibers) in Meckel's diverticulum

- Vesicodiverticular fistula[7]

Pathophysiology

The omphalomesenteric duct (omphaloenteric duct, vitelline duct or yolk stalk) normally connects the embryonic midgut to the yolk sac ventrally, providing nutrients to the midgut during embryonic development. The vitelline duct narrows progressively and disappears between the 5th and 8th weeks gestation.

In Meckel's diverticulum, the proximal part of vitelline duct fails to regress and involute, which remains as a remnant of variable length and location.[14] The solitary diverticulum lies on the antimesenteric border of the ileum (opposite to the mesenteric attachment) and extends into the umbilical cord of the embryo.[6] The left and right vitelline arteries originate from the primitive dorsal aorta, and travel with the vitelline duct. The right becomes the superior mesenteric artery that supplies a terminal branch to the diverticulum, while the left involutes.[15] Having its own blood supply, Meckel's diverticulum is susceptible to obstruction or infection.

Meckel's diverticulum is located in the distal ileum, usually within 60–100 cm (2 feet) of the ileocecal valve. This blind segment or small pouch is about 3–6 cm (2 inch) long and may have a greater lumen diameter than that of the ileum.[18] It runs antimesenterically and has its own blood supply. It is a remnant of the connection from the yolk sac to the small intestine present during embryonic development. It is a true diverticulum, consisting of all 3 layers of the bowel wall which are mucosa, submucosa and muscularis propria.[15]

As the vitelline duct is made up of pluripotent cell lining, Meckel’s diverticulum may harbor abnormal tissues, containing embryonic remnants of other tissue types. Jejunal, duodenal mucosa or Brunner's tissue were each found in 2% of ectopic cases. Heterotopic rests of gastric mucosa and pancreatic tissue are seen in 60% and 6% of cases respectively. Heterotopic means the displacement of an organ from its normal anatomic location.[19] Inflammation of this Meckel's diverticulum may mimic appendicitis. Therefore, during appendectomy, ileum should be checked for the presence of Meckel's diverticulum, if it is found to be present it should be removed along with appendix.

A memory aid is the rule of 2s:[20]

- 2% (of the population)

- 2 feet (proximal to the ileocecal valve)

- 2 inches (in length)

- 2 types of common ectopic tissue (gastric and pancreatic)

- 2 years is the most common age at clinical presentation

- 2:1 male:female ratio

However, the exact values for the above criteria range from 0.2–5 (for example, prevalence is probably 0.2–4%).

It can also be present as an indirect hernia, typically on the right side, where it is known as a "Hernia of Littré". A case report of strangulated umbilical hernia with Meckel's diverticulum has also been published in the literature.[21] Furthermore, it can be attached to the umbilical region by the vitelline ligament, with the possibility of vitelline cysts, or even a patent vitelline canal forming a vitelline fistula when the umbilical cord is cut. Torsions of intestine around the intestinal stalk may also occur, leading to obstruction, ischemia, and necrosis.

Diagnosis

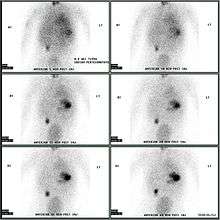

A technetium-99m (99mTc) pertechnetate scan, also called Meckel scan, is the investigation of choice to diagnose Meckel's diverticula in children. This scan detects gastric mucosa; since approximately 50% of symptomatic Meckel's diverticula have ectopic gastric or pancreatic cells contained within them,[22] this is displayed as a spot on the scan distant from the stomach itself. In children, this scan is highly accurate and noninvasive, with 95% specificity and 85% sensitivity;[15] however, in adults the test is only 9% specific and 62% sensitive.[23]

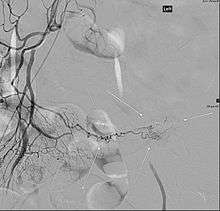

Patients with these misplaced gastric cells may experience peptic ulcers as a consequence. Therefore, other tests such as colonoscopy and screenings for bleeding disorders should be performed, and angiography can assist in determining the location and severity of bleeding. Colonoscopy might be helpful to rule out other sources of bleeding but it is not used as an identification tool.

Angiography might identify brisk bleeding in patients with Meckel's diverticulum.[15]

Ultrasonography could demonstrate omphaloenteric duct remnants or cysts.[24] Computed tomography (CT scan) might be a useful tool to demonstrate a blind ended and inflamed structure in the mid-abdominal cavity, which is not an appendix.[15]

In asymptomatic patients, Meckel's diverticulum is often diagnosed as an incidental finding during laparoscopy or laparotomy.

Treatment

Treatment is surgical, potentially with a laparoscopic resection.[15] In patients with bleeding, strangulation of bowel, bowel perforation or bowel obstruction, treatment involves surgical resection of both the Meckel's diverticulum itself along with the adjacent bowel segment, and this procedure is called a "small bowel resection".[15] In patients without any of the aforementioned complications, treatment involves surgical resection of the Meckel's diverticulum only, and this procedure is called a simple diverticulectomy.[15]

With regards to asymptomatic Meckel's diverticulum, some recommend that a search for Meckel's diverticulum should be conducted in every case of appendectomy/laparotomy done for acute abdomen, and if found, Meckel's diverticulectomy or resection should be performed to avoid secondary complications arising from it.[25]

Epidemiology

Meckel's diverticulum occurs in about 2% of the population.[19] Prevalence in males is 3–5 times higher than in females.[18] Only 2% of cases are symptomatic, which usually presents among children at the age of 2.[6]

Most cases of Meckel's diverticulum are diagnosed when complications manifest or incidentally in unrelated conditions such as laparotomy, laparoscopy or contrast study of the small intestine. Classic presentation in adults includes intestinal obstruction and inflammation of the diverticulum (diverticulitis). Painless rectal bleeding most commonly occurs in toddlers.

Inflammation in the ileal diverticulum has symptoms that mimic appendicitis, therefore its diagnosis is of clinical importance. Detailed knowledge of the pathophysiological properties is essential in dealing with the life-threatening complications of Meckel's diverticulum.[15]

References

- Elsayes KM, Menias CO, Harvin HJ, Francis IR (July 2007). "Imaging manifestations of Meckel's diverticulum". AJR Am J Roentgenol. 189 (1): 81–8. doi:10.2214/AJR.06.1257. PMID 17579156.

- Meckel's diverticulum at Who Named It?

- J. F. Meckel. Über die Divertikel am Darmkanal. Archiv für die Physiologie, Halle, 1809, 9: 421–453.

- Thurley PD, Halliday KE, Somers JM, Al-Daraji WI, Ilyas M, Broderick NJ (February 2009). "Radiological features of Meckel's diverticulum and its complications". Clin Radiol. 64 (2): 109–18. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2008.07.012. PMID 19103339.

- Darlington CD, Anitha GF. Meckel's diverticulitis masquerading as acute pancreatitis: A diagnostic dilemma. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine 2017; 21:789‑92.

- Schoenwolf, G. C., & Larsen, W. J. (2009). Larsen's human embryology (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier.

- Johnston A. O.; Moore T. (1976). "Complications of Meckel's diverticulum". British Journal of Surgery. 63 (6): 453–454. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800630612. PMID 1084202.

- Sagar J.; Kumar V.; Shah D. K. (2006). "Meckel's diverticulum: A systematic review". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 99 (10): 501–505. doi:10.1258/jrsm.99.10.501. PMC 1592061. PMID 17021300.

- Karaman A.; Karaman I.; Cavusoaglu Y. H.; Erdoagan D.; Aslan M. K. (2010). "Management of asymptomatic or incidental meckels diverticulum". Indian Pediatrics. 47 (12): 1055–1057. doi:10.1007/s13312-010-0176-1. PMID 19671945.

- Higaki S.; Saito Y.; Akazawa A.; Okamoto T.; Hirano A.; Takeo Y.; Okita K. (2001). "Bleeding Meckel's diverticulum in an adult". Hepato-Gastroenterology. 48 (42): 1628–1630. PMID 11813588.

- Al-Onaizi I.; Al-Awadi F.; Al-Dawood A. L. (2002). "Iron deficiency anaemia: An unusual complication of Meckel's diverticulum". Medical Principles and Practice. 11 (4): 214–217. doi:10.1159/000065810. PMID 12424418.

- Sharma R.; Jain V. (2008). "Emergency surgery for Meckel's diverticulum". World J Emerg Surg. 3 (27): 1–8. doi:10.1186/1749-7922-3-27. PMC 2533303. PMID 18700974.

- Tan, Y. M., & Zheng, Z. X. (2005). Recurrent torsion of a giant Meckel's diverticulum. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 50(7), 1285–1287.

- Drake, R. L., Vogl, W., Mitchell, A. W. M., Gray, H., & Gray, H. (2010). Gray's anatomy for students (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier.

- Mattei, P. (2011). Fundamentals of Pediatric Surgery. New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC.

- Pariza, G., Mavrodin, C. I., & Ciurea, M. (2009). Complicated meckel's diverticulum in adult pathology. [Diverticulul Meckel complicat in patologia adultului] Chirurgia (Bucharest, Romania : 1990), 104(6), 745–748.

- Martin, E. (2010). Concise colour medical dictionary (5th ed.) Oxford University Press.

- Moore, K. L., Persaud, T. V. N., & Torchia, M. G. (2013). The developing human: Clinically oriented embryology (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders.

- Robbins, S. L., Kumar, V., & Cotran, R. S. (2010). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier

- F. Charles Brunicardi, Dana K. Anderson, Timothy R. Billiar, et al. Small Intestine. In: Ali Tavakkoli, Stanley W. Ashley, Michael J. Zinner: Schwartz's Principles of Surgery. 10 ed. United states: McGraw-Hill;2015

- Tiu A, Lee D (2006). "An unusual manifestation of Meckel's diverticulum: strangulated paraumbilical hernia". N. Z. Med. J. 119 (1236): U2034. PMID 16807577.

- Martin JP, Connor PD, Charles K (February 2000). "Meckel's diverticulum". Am Fam Physician. 61 (4): 1037–42, 1044. PMID 10706156.

- Uppal K, Tubbs RS, Matusz P, Shaffer K, Loukas M (May 2011). "Meckel's diverticulum: a review". Clin Anat. 24 (4): 416–422. doi:10.1002/ca.21094. PMID 21322060.

- Samain, J; Maeyaert, S; Geusens, E; Mussen, E (Mar–Apr 2012). "Sonographic findings of Meckel's diverticulitis". JBR-BTR : Organe de la Societe Royale Belge de Radiologie (SRBR) = Orgaan van de Koninklijke Belgische Vereniging voor Radiologie (KBVR). 95 (2): 103. PMID 22764670.

- Tauro LF, George C, Rao BS, Martis JJ, Menezes LT, Shenoy HD (2010). "Asymptomatic Meckel's diverticulum in adults: is diverticulectomy indicated?". Saudi J Gastroenterol. 16 (3): 198–202. doi:10.4103/1319-3767.65199. PMC 3003224. PMID 20616416.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Meckel's diverticulum. |