Left ventricular hypertrophy

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is thickening of the heart muscle of the left ventricle of the heart, that is, left-sided ventricular hypertrophy.

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | |

|---|---|

| |

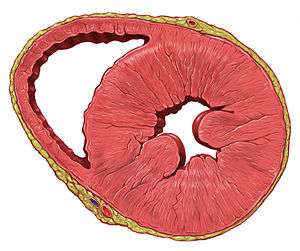

| A heart with left ventricular hypertrophy in short-axis view | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Complications | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Heart failure[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Echocardiography, cardiovascular MRI[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Athletic heart syndrome |

Causes

While ventricular hypertrophy occurs naturally as a reaction to aerobic exercise and strength training, it is most frequently referred to as a pathological reaction to cardiovascular disease, or high blood pressure.[2] It is one aspect of ventricular remodeling.

While LVH itself is not a disease, it is usually a marker for disease involving the heart.[3] Disease processes that can cause LVH include any disease that increases the afterload that the heart has to contract against, and some primary diseases of the muscle of the heart.

Causes of increased afterload that can cause LVH include aortic stenosis, aortic insufficiency and hypertension. Primary disease of the muscle of the heart that cause LVH are known as hypertrophic cardiomyopathies, which can lead into heart failure.

Long-standing mitral insufficiency also leads to LVH as a compensatory mechanism.

Associated genes include OGN, osteoglycin.[4]

Diagnosis

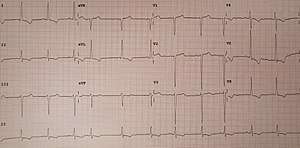

The principal method to diagnose LVH is echocardiography, with which the thickness of the muscle of the heart can be measured. The electrocardiogram (ECG) often shows signs of increased voltage from the heart in individuals with LVH, so this is often used as a screening test to determine who should undergo further testing.

Echocardiography

Two dimensional echocardiography can produce images of the left ventricle. The thickness of the left ventricle as visualized on echocardiography correlates with its actual mass. Normal thickness of the left ventricular myocardium is from 0.6 to 1.1 cm (as measured at the very end of diastole. If the myocardium is more than 1.1 cm thick, the diagnosis of LVH can be made.

ECG criteria

There are several sets of criteria used to diagnose LVH via electrocardiography.[5] None of them are perfect, though by using multiple criteria sets, the sensitivity and specificity are increased.

- S in V1 + R in V5 or V6 (whichever is larger) ≥ 35 mm (≥ 7 large squares)

- R in aVL ≥ 11 mm

The Cornell voltage criteria[8] for the ECG diagnosis of LVH involve measurement of the sum of the R wave in lead aVL and the S wave in lead V3. The Cornell criteria for LVH are:

- S in V3 + R in aVL > 28 mm (men)

- S in V3 + R in aVL > 20 mm (women)

The Romhilt-Estes point score system ("diagnostic" >5 points; "probable" 4 points):

| ECG Criteria | Points |

Voltage Criteria (any of):

|

3 |

ST-T Abnormalities:

|

3 |

| Negative terminal P mode in V1 1 mm in depth and 0.04 sec in duration (indicates left atrial enlargement) | 3 |

| Left axis deviation (QRS of -30° or more) | 2 |

| QRS duration ≥0.09 sec | 1 |

| Delayed intrinsicoid deflection in V5 or V6 (>0.05 sec) | 1 |

Other voltage-based criteria for LVH include:

- Lead I: R wave > 14 mm

- Lead aVR: S wave > 15 mm

- Lead aVL: R wave > 12 mm

- Lead aVF: R wave > 21 mm

- Lead V5: R wave > 26 mm

- Lead V6: R wave > 20 mm

Treatment

The enlargement is not permanent in all cases, and in some cases the growth can regress with the reduction of blood pressure.[9]

LVH may be a factor in determining treatment or diagnosis for other conditions. For example, LVH causes a patient to have an irregular ECG. Patients with LVH may have to participate in more complicated and precise diagnostic procedures, such as imaging, in situations in which a physician could otherwise give advice based on an ECG.[10][11]

References

- Maron, Barry J; Maron, Martin S (2013-01-19). "Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy". Lancet. Elsevier BV. 381 (9862): 242–255. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60397-3. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 22874472.

- "Ask the doctor: Left Ventricular Hypertrophy". Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- Meijs MF, Bots ML, Vonken EJ, et al. (2007). "Rationale and design of the SMART Heart study: A prediction model for left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertension". Neth Heart J. 15 (9): 295–8. doi:10.1007/BF03086003. PMC 1995099. PMID 18030317.

- Petretto E, Sarwar R, Grieve I, Lu H, Kumaran MK, Muckett PJ, Mangion J, Schroen B, Benson M, Punjabi PP, Prasad SK, Pennell DJ, Kiesewetter C, Tasheva ES, Corpuz LM, Webb MD, Conrad GW, Kurtz TW, Kren V, Fischer J, Hubner N, Pinto YM, Pravenec M, Aitman TJ, Cook SA (May 2008). "Integrated genomic approaches implicate osteoglycin (Ogn) in the regulation of left ventricular mass". Nat. Genet. 40 (5): 546–52. doi:10.1038/ng.134. PMC 2742198. PMID 18443592.

- "Lesson VIII - Ventricular Hypertrophy". Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- Sokolow M, Lyon TP. The ventricular complex in left ventricular hypertrophy as obtained by unipolar precordial and limb leads. Am Heart J. 1949;37:161–186.

- Okin, Peter M.; Roman, Mary J.; Devereux, Richard B.; Pickering, Thomas G.; Borer, Jeffrey S.; Kligfield, Paul (1998). "Time-Voltage QRS Area of the 12-Lead Electrocardiogram : Detection of Left Ventricular Hypertrophy -- Okin et al. 31 (4): 937 -- Hypertension". Hypertension. 31 (4): 937–942. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.503.8356. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.31.4.937. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- Casale PN, Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Campo E, Kligfield P (1987). "Improved sex-specific criteria of left ventricular hypertrophy for clinical and computer interpretation of electrocardiograms: validation with autopsy findings". Circulation. 75 (3): 565–72. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.75.3.565. PMID 2949887.

- Gradman AH, Alfayoumi F (2006). "From left ventricular hypertrophy to congestive heart failure: management of hypertensive heart disease". Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 48 (5): 326–41. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2006.02.001. PMID 16627048.

- American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF), Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, archived from the original (PDF) on April 16, 2012, retrieved August 17, 2012

- Anderson, J. L.; Adams, C. D.; Antman, E. M.; Bridges, C. R.; Califf, R. M.; Casey, D. E.; Chavey, W. E.; Fesmire, F. M.; Hochman, J. S.; Levin, T. N.; Lincoff, A. M.; Peterson, E. D.; Theroux, P.; Wenger, N. K.; Wright, R. S. (2007). "ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction): Developed in Collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons: Endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine". Circulation. 116 (7): 803. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185752.