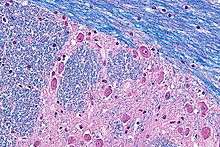

Luxol fast blue stain

Luxol fast blue stain, abbreviated LFB stain or simply LFB, is a commonly used stain to observe myelin under light microscopy, created by Heinrich Klüver and Elizabeth Barrera in 1953.[1] LFB is commonly used to detect demyelination in the central nervous system (CNS), but cannot discern myelination in the peripheral nervous system.[2]

Procedure

Luxol fast blue is a copper phthalocyanine dye that is soluble in alcohol and is attracted to bases found in the lipoproteins of the myelin sheath.[3][4]

Under the stain, myelin fibers appear blue, neuropil appears pink, and nerve cells appear purple. Tissues sections are treated over an extended period of time (usually overnight) and then differentiated with a lithium carbonate solution.[4]

Combination methods

The combination of LFB with a variety of common staining methods provides the most useful and reliable method for the demonstration of pathological processes in the CNS.[2] It is often combined with H&E stain (hematoxylin and eosin), which is abbreviated H-E-LFB, H&E-LFB. Other common staining methods include the periodic acid-Schiff, Oil Red O, phosphotungstic acid, and Holmes silver nitrate method.[2]

Disease states

Studies have demonstrated that in both, human and mice, traumatic brain injury is associated with ongoing white matter degeneration with survival > 1 year post-injury.[5][6]

See also

References

- Kluver H., Barrera E. (1953). "A method for the combined staining of cells and fibers in the Nervous system". J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 12 (4): 400–403. doi:10.1097/00005072-195312040-00008. PMID 13097193.

- Shin J. Oh (2002). Color Atlas of Nerve Biopsy Pathology. CRC Press. pp. 191–. ISBN 978-0-8493-1676-0. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- Bruce-Gregorios, Jocelyn (2006). Histophatologic Techniques. Goodwill Trading Co., Inc. pp. 241–. ISBN 978-971-12-0270-5. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- Peter A. Humphrey; Louis P. Dehner; John D. Pfeifer (2008). The Washington Manual of Surgical Pathology: Department of Pathology and Immunology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 681–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6527-5. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- Jonhson, VE; Stewart, JE (January 2013). "Inflammation and white matter degeneration persist for years after a single traumatic brain injury". Brain. 136 (1): 28–42. doi:10.1093/brain/aws322. PMC 3562078. PMID 23365092.

- Mouzon, B; Bachmeier, C (February 2014). "Chronic neuropathological and neurobehavioral changes in a repetitive mild traumatic brain injury model". Ann. Neurol. 75 (2): 241–254. doi:10.1002/ana.24064. PMID 24243523.