Kwashiorkor

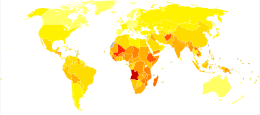

Kwashiorkor is a form of severe protein malnutrition characterized by edema and an enlarged liver with fatty infiltrates. It is caused by sufficient calorie intake, but with insufficient protein consumption, which distinguishes it from marasmus. Kwashiorkor cases occur in areas of famine or poor food supply.[1] Cases in the developed world are rare.[2]

| Kwashiorkor | |

|---|---|

| |

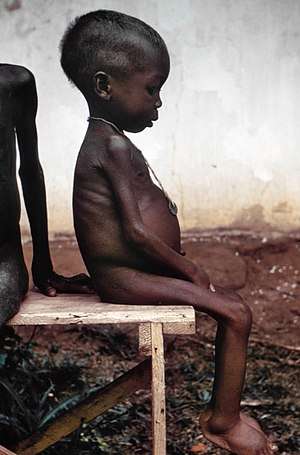

| One of many children with kwashiorkor in relief camps during the Biafra War | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Pediatrics |

Jamaican pediatrician Cicely Williams introduced the term in a 1935 Lancet article, two years after she published the disease's first formal description.[3][4] The name is derived from the Ga language of coastal Ghana, translated as "the sickness the baby gets when the new baby comes" or "the disease of the deposed child",[5] and reflecting the development of the condition in an older child who has been weaned from the breast when a younger sibling comes.[6] Breast milk contains amino acids vital to a child's growth. In at-risk populations, kwashiorkor may develop after a mother weans her child from breast milk, replacing it with a diet high in carbohydrates, especially sugar.

Signs and symptoms

The defining sign of kwashiorkor in a malnourished child is pitting edema (swelling of the ankles and feet). Other signs include a distended abdomen, an enlarged liver with fatty infiltrates, thinning of hair, loss of teeth, skin depigmentation and dermatitis. Children with kwashiorkor often develop irritability and anorexia. Generally, the disease can be treated by adding protein to the diet; however, it can have a long-term impact on a child's physical and mental development, and in severe cases may lead to death.

In dry climates, marasmus is the more frequent disease associated with malnutrition. Another malnutrition syndrome includes cachexia, although it is often caused by underlying illnesses. These are important considerations in the treatment of the patients.

Causes

The precise etiology of kwashiorkor remains unclear.[7][8][9][10][11] Several hypotheses have been proposed that are associated with and explain some, but not all aspects of the pathophysiology of kwashiorkor. They include, but are not limited to protein deficiency causing hypoalbuminemia, amino acid deficiency, oxidative stress, and gut microbiome changes.[7][11][12]

Low protein intake and hypoalbuminemia

Kwashiorkor is a severe form of malnutrition associated with a deficiency in dietary protein.[8] The extreme lack of protein causes an osmotic imbalance in the gastro-intestinal system causing swelling of the gut diagnosed as an edema or retention of water.[4]

Extreme fluid retention observed in individuals suffering from kwashiorkor is a direct result of irregularities in the lymphatic system and an indication of capillary exchange. The lymphatic system serves three major purposes: fluid recovery, immunity, and lipid absorption. Victims of kwashiorkor commonly exhibit reduced ability to recover fluids, immune system failure, and low lipid absorption, all of which result from a state of severe undernourishment. Fluid recovery in the lymphatic system is accomplished by re-absorption of water and proteins which are then returned to the blood. Compromised fluid recovery results in the characteristic belly distension observed in highly malnourished children.[14]

Capillary exchange between the lymphatic system and the bloodstream is stunted due to the inability of the body to effectively overcome the hydrostatic pressure gradient. Proteins, mainly albumin, are responsible for creating the colloid osmotic pressure (COP) observed in the blood and tissue fluids. The difference in the COP of the blood and tissue is called the oncotic pressure. The oncotic pressure is in direct opposition with the hydrostatic pressure and tends to draw water back into the capillary by osmosis. However, due to the lack of proteins, no substantial pressure gradient can be established to draw fluids from the tissue back into the blood stream. This results in the pooling of fluids, causing the swelling and distention of the abdomen.[15]

The low protein intake leads to some specific signs: edema of the hands and feet, irritability, anorexia, a desquamative rash, hair discolouration, and a large fatty liver. The typical swollen abdomen is due to two causes: ascites because of hypoalbuminemia (low oncotic pressure), and enlarged fatty liver.[16]

Ignorance of nutrition can be a cause. Dr. Michael Latham, former director of the Program in International Nutrition at Cornell University, along with Keith Rosenberg cited a case where parents fed their child cassava failed to recognize malnutrition because of the edema caused by the syndrome and insisted the child was well-nourished despite the lack of dietary protein.[17]

Protein should be supplied only for anabolic purposes. The catabolic needs should be satisfied with carbohydrate and fat. Protein catabolism involves the urea cycle, which is located in the liver and can easily overwhelm the capacity of an already damaged organ. The resulting liver failure can be fatal. This means in patients suffering from kwashiorkor, protein must be introduced back into the diet gradually. Clinical solutions include weaning the affected with milk products and increasing the intake of proteinaceous material progressively to daily recommended amounts.

Diagnosis

Kwashiorkor is a subtype of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) that is characterized by bilateral peripheral pitting edema, low mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC < 115 mm), and a low weight-for-height Z-score (WHZ, Z < -3).[18][19][8] Additional clinical findings on physical exam include marked muscle atrophy, abdominal distension, dermatitis, and hepatomegaly.[8][20] Kwashiorkor is distinguished from marasmus by the presence of edema.

WHO criteria for clinical assessment of malnutrition are based on the degree of wasting (MUAC), stunting (weight-for-height Z-score), and the presence of edema (mild to severe).[21]

Treatment

WHO guidelines outline 10 general principles for the inpatient management of severely malnourished children.[21][22]

- Treat/prevent hypoglycemia

- Treat/prevent hypothermia

- Treat/prevent dehydration

- Correct electrolyte imbalance

- Treat/prevent infection

- Correct micronutrient deficiencies

- Start cautious feeding

- Achieve catch-up growth

- Provide sensory stimulation and emotional support

- Prepare for follow-up after recovery

Both clinical subtypes of severe acute malnutrition (kwashiorkor and marasmus) are treated similarly.[11][21]

Prevention

In order to avoid refeeding syndrome, the person must be rehabilitated with small but frequent rations, given every two to four hours. During week one, a diet high in sugar and carbs is gradually enriched in protein as well as essential elements: sweet milk with mineral salts and vitamins. The diet may include lactases—so that children who have developed lactose intolerance can ingest dairy products—and antibiotics—to compensate for immunodeficiency. After two to three weeks, the milk is replaced by boiled cereals fortified with minerals and vitamins until the person's mass is at least 80% of normal weight. Traditional food can then be reintroduced. The child is considered healed when their mass reaches 85% of normal.

Prognosis

Disorders usually resolve after early treatment. If the treatment is delayed, the overall health of the child is improved but physical (reduced) and intellectual (mental disabilities) sequelae are feared. Without treatment or if treatment occurs too late, death is inevitable.

A high risk of death is identified by a brachial perimeter < 11 cm or by a weight-to-height threshold < −3 SD. In practice, malnourished children with edema are suffering from potentially life-threatening severe malnutrition.

See also

References

- Krebs NF, Primak LE, Hambridge KM. Normal childhood nutrition & its disorders. In: Current Pediatric Diagnosis & Treatment. McGraw-Hill.

- Liu T, Howard RM, Mancini AJ, Weston WL, Paller AS, Drolet BA, et al. (May 2001). "Kwashiorkor in the United States: fad diets, perceived and true milk allergy, and nutritional ignorance". Archives of Dermatology. 137 (5): 630–6. PMID 11346341.

- Williams CD (July 1983) [1933]. "Fifty years ago. Archives of Diseases in Childhood 1933. A nutritional disease of childhood associated with a maize diet". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 58 (7): 550–60. doi:10.1136/adc.58.7.550. PMC 1628206. PMID 6347092.

- Williams CD, Oxon BM, Lond H (1935). "Kwashiorkor: a nutritional disease of children associated with a maize diet. 1935". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 81 (12): 912–3. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)94666-X. PMC 2572388. PMID 14997245. Reprint: Williams CD, Oxon BM, Lond H (2003). "Kwashiorkor: a nutritional disease of children associated with a maize diet. 1935". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 81 (12): 912–3. PMC 2572388. PMID 14997245.

- Stanton J (2001). "Listening to the Ga: Cicely Williams' discovery of kwashiorkor on the Gold Coast". Clio Medica. 61: 149–71. PMID 11603151.

- "Merriam Webster Dictionary". Retrieved 2009-04-05.

- Briend A (2014). "Kwashiorkor: still an enigma – the search must go on" (PDF). Emergency Nutrition Network. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- Benjamin O, Lappin SL (2019). "Kwashiorkor". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29939653. Retrieved 2019-08-01.

- Coulthard MG (May 2015). "Oedema in kwashiorkor is caused by hypoalbuminaemia". Paediatrics and International Child Health. 35 (2): 83–9. doi:10.1179/2046905514Y.0000000154. PMC 4462841. PMID 25223408.

- Pham TP, Tidjani Alou M, Bachar D, Levasseur A, Brah S, Alhousseini D, et al. (June 2019). "Gut Microbiota Alteration is Characterized by a Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria Bloom in Kwashiorkor and a Bacteroidetes Paucity in Marasmus". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 9084. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-45611-3. PMC 6591176. PMID 31235833.

- Smith MI, Yatsunenko T, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Mkakosya R, Cheng J, et al. (February 2013). "Gut microbiomes of Malawian twin pairs discordant for kwashiorkor". Science. 339 (6119): 548–54. doi:10.1126/science.1229000. PMC 3667500. PMID 23363771.

- Velly H, Britton RA, Preidis GA (March 2017). "Mechanisms of cross-talk between the diet, the intestinal microbiome, and the undernourished host". Gut Microbes. 8 (2): 98–112. doi:10.1080/19490976.2016.1267888. PMC 5390823. PMID 27918230.

- "Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2002" (xls). World Health Organization. 2002.

- "Nova et Vetera". The British Medical Journal. 2 (4673): 284. 1950. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4673.267.

- Saladin K (2012). Anatomy and Physiology (6th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. pp. 766–767, 809–811. ISBN 978-0-07-337825-1.

- Tierney EP, Sage RJ, Shwayder T (May 2010). "Kwashiorkor from a severe dietary restriction in an 8-month infant in suburban Detroit, Michigan: case report and review of the literature". International Journal of Dermatology. 49 (5): 500–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04253.x. PMID 20534082.

- "Malnutrition in Third World Countries". www.religion-online.org.

- "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2019-08-01.

- Roberfroid D, Hammami N, Mehta P, Lachat C, Verstraeten R, Weise Prinzo Z, Huybregts L, Kolsteren P. "Management of oedematous malnutrition in infants and children aged >6 months: a systematic review of the evidence" (PDF).

- Heilskov S, Rytter MJ, Vestergaard C, Briend A, Babirekere E, Deleuran MS (August 2014). "Dermatosis in children with oedematous malnutrition (Kwashiorkor): a review of the literature". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 28 (8): 995–1001. doi:10.1111/jdv.12452. PMID 24661336.

- "Updates on the Management of Severe Acute Malnutrition in Infants and Children" (PDF). WHO. 2013.

- Ashworth A (2003). "Guidelines for the inpatient treatment of severely malnourished children" (PDF). WHO.

External links

- https://m.delugerpg.com/