Klatskin tumor

A Klatskin tumor (or hilar cholangiocarcinoma) is a cholangiocarcinoma (cancer of the biliary tree) occurring at the confluence of the right and left hepatic bile ducts. The disease was named after Gerald Klatskin, who in 1965 described 15 cases and found some characteristics for this type of cholangiocarcinoma[1][2][3]

| Klatskin tumor | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hilar cholangiocarcinoma |

| |

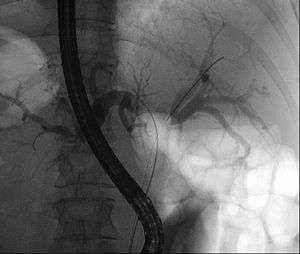

| Klatskin tumor during ERCP. Wires were inserted into the left and right biliary systems. Both parts were injected through a tube with contrast, but there is no contrast visible in the area of confluence of the two systems | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

Cause

The cause of cholangiocarcinoma has not been defined. A number of pathologic conditions, however, resulting in either acute or chronic biliary tract epithelial injury may predispose to malignant change. Primary sclerosing cholangitis, an idiopathic inflammatory condition of the biliary tree, has been associated with the development of cholangiocarcinoma in up to 40% of patients.[4][5] Congenital biliary cystic disease, such as choledochal cysts or Caroli's disease,[6][7][8] has also been associated with malignant transformation in up to 25% of cases. These conditions appear to be related to an anomalous pancreatico-biliary duct junction and, perhaps, are related to the reflux of pancreatic secretions into the bile duct. Chronic biliary tract parasitic infection, seen commonly in Southeast Asia due to Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini, has also been identified as a risk factor.[9] Although gallstones and cholecystectomy are not thought to be associated with an increased incidence of cholangiocarcinoma, hepatolithiasis and choledocholithiasis may predispose to malignant change. Further, industrial exposure to asbestos and nitrosamines, and the use of the radiologic contrast agent, Thorotrast (thorium dioxide), are considered to be risk factors for the development of cholangiocarcinoma.

Diagnosis

Levels of the tumor markers carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA 125 are abnormally high in the bloodstreams of patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and Klatskin tumor. The serum CA 19-9 in particular may be very high.[10] The ultrasonography (and the use of Doppler modes) permit definitive diagnosis of a large number of lesions and the involvement of hepatic hilum,[11] but it is less sensitive than CT or MRI in detecting focal lesions.[12][13] Ultrasonography always detects dilatation of the bile ducts, but more rarely the tumor itself.[14] Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is a good non-invasive alternative to these other procedure. This technique demonstrates hepatic parenchyma and it's accurate for detecting nodular carcinomas and infiltrating lesions.[15]

Treatment

Because of their location, these tumors tend to become symptomatic late in their development and therefore are not usually resectable at the time of presentation. Complete resection of the tumor, especially in early-stage disease, offers hope of long-term survival. However, patients that are candidates for resectability are few and moreover many of these patients will have a relapse despite apparent removal of the tumor. The type of surgery and the extent of the resection depend on the location of the tumor and the degree of extension.[16] In some case, the obstruction, jaundice may present early and compel the patient to seek help. More often, liver resection is not a viable option because many patients are of advanced age, have multiple co-pathologies and are therefore at high risk.[17] Of late there has been renewed interest in liver transplantation from deceased donors along with add on therapy.[18] Prognosis remains poor.

Epidemiology

Approximately 15,000 new cases of liver and biliary tract carcinoma are diagnosed annually in the United States, with roughly 10% of these cases being Klatskin tumors. Cholangiocarcinoma accounts for approximately 2% of all cancer diagnoses, with an overall incidence of 1.2/100,000 individuals. Two-thirds of cases occur in patients over the age of 65, with a near ten-fold increase in patients over 80 years of age. The incidence is similar in both men and women.

References

- Chamberlain RS, Blumgart LH (2000). "Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a review and commentary". Annals of Surgical Oncology. 7 (1): 55–66. doi:10.1007/s10434-000-0055-4. PMID 10674450.

- Fenster LF (Jan–Feb 1979). "Gerald Klatskin". Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 52 (1): 1–3. PMC 2595709.

- Burcharth F (1988). "Klatskin tumours". Acta Chirurgica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 541: 63–69. PMID 2455407.

- Kuang D, Wang GP (2010). "Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: pathology and tumor biology". Frontiers of Medicine in China. 4 (4): 371–377. doi:10.1007/s11684-010-0130-6. PMID 21110142.

- Boberg KM, Bergquist A, Mitchell S, Pares A, Rosina F, Broomé U, Chapman R, Fausa O, Egeland T, Rocca G, Schrumpf E (2002). "Cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis: risk factors and clinical presentation". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 37 (10): 1205–1211. doi:10.1080/003655202760373434. PMID 12408527.

- Faría G, de Aretxabala X, Sierralta A, Flores P, Burgos L (2001). "[Primary cholangiocarcinoma associated with Caroli disease]". Revista Médica de Chile (in Spanish). 129 (12): 1433–1438. PMID 12080880.

- Totkas S, Hohenberger P (2000). "Cholangiocellular carcinoma associated with segmental Caroli's disease". European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 26 (5): 520–521. doi:10.1053/ejso.1999.0936. PMID 11016478.

- Falco E, Nardini A, Celoria G, Briglia R, Stefani R, Gadducci G, Belloni E (1993). "[Caroli's disease associated with cholangiocarcinoma. A case of our own observation]". Minerva Chirurgica (in Italian). 48 (17): 961–964. PMID 8290138.

- Tannapfel A, Wittekind C (2004). "[Gallbladder and bile duct carcinoma. Biology and pathology]". Internist (Berlin) (in German). 45 (1): 33–41. doi:10.1007/s00108-003-1110-6. PMID 14735242.

- Qin XL, Wang ZR, Shi JS, Lu M, Wang L, He QR (2004). "Utility of serum CA19-9 in diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma: in comparison with CEA". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 10 (3): 427–432. doi:10.3748/wjg.v10.i3.427. PMC 4724921. PMID 14760772. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- Tchelepi H, Ralls PW (2004). "Ultrasound of focal liver masses". Ultrasound Quarterly. 20 (4): 155–169. doi:10.1097/00013644-200412000-00002. PMID 15602218. Retrieved 2018-02-10.

- Harvey CJ, Albrecht T (2001). "Ultrasound of focal liver lesions". European Radiology. 11 (9): 1578–1593. doi:10.1007/s003300101002. PMID 11511877.

- Hussain SM, Semelka RC (2005). "Hepatic imaging: comparison of modalities". Radiol. Clin. North Am. 43 (5): 929–47, ix. doi:10.1016/j.rcl.2005.05.006. PMID 16098348.

- Acalovschi M (2004). "Cholangiocarcinoma: risk factors, diagnosis and management". Romanian Journal of Internal Medicine. 42 (1): 41–58. PMID 15529594.

- Bley TA, Pache G, Saueressig U, Frydrychowicz A, Langer M, Schaefer O (2007). "State of the art 3D MR-cholangiopancreatography for tumor detection". In Vivo. 21 (5): 885–889. PMID 18019429. Retrieved 2018-02-10.

- Clary B, Jarnigan W, Pitt H, Gores G, Busuttil R, Pappas T (2004). "Hilar cholangiocarcinoma". Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 8 (3): 298–302. doi:10.1016/j.gassur.2003.12.004. PMID 15019927.

- Jarnagin WR, Shoup M (2004). "Surgical management of cholangiocarcinoma". Seminars in Liver Disease. 24 (2): 189–199. doi:10.1055/s-2004-828895. PMID 15192791.

- Heimbach JK, Haddock MG, Alberts SR, Nyberg SL, Ishitani MB, Rosen CB, Gores GJ (2004). "Transplantation for hilar cholangiocarcinoma". Liver Transplantation. 10 (10 Suppl 2): S65–568. doi:10.1002/lt.20266. PMID 15382214.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |