Jones fracture

A Jones fracture is a break between the base and middle part of the fifth metatarsal of the foot.[8] It results in pain near the midportion of the foot on the outside.[2] There may also be bruising and difficulty walking.[3] Onset is generally sudden.[4]

| Jones fracture | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Fracture of the metaphysis of the fifth metatarsal[1] |

| |

| Jones fracture as seen on Xray | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine, orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Pain near the midportion of the foot on the outside, bruising[2][3] |

| Usual onset | Sudden[4] |

| Duration | 6-12 weeks to heal[5] |

| Causes | Bending the foot inwards when the toes are pointed[6] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, X-rays[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Pseudo-Jones fracture, normal growth plate[3][7] |

| Treatment | Non-weight bearing, cast, surgery[5] |

The fracture typically occurs when the toes are pointed and the foot bends inwards.[6][2] This movement may occur when changing direction while the heel is off the ground such in dancing, tennis, or basketball.[9][10] Diagnosis is generally suspected based on symptoms and confirmed with X-rays.[3]

Initial treatment is typically in a cast, without any walking on it, for at least six weeks.[5] If after this period of time healing has not occurred a further six weeks of casting may be recommended.[5] Due to poor blood supply in this area, the break sometimes does not heal and surgery is required.[3] In athletes or if the pieces of bone are separated surgery may be considered sooner.[5][8] The fracture was first described in 1902 by orthopedic surgeon Robert Jones, who sustained the injury while dancing.[11][4]

Diagnosis

A person with a Jones fracture may not realize that a fracture has occurred. Diagnosis includes the palpation of an intact peroneus brevis tendon, and demonstration of local tenderness distal to the tuberosity of the fifth metatarsal, and localized over the diaphysis of the proximal metatarsal. Bony crepitus is unusual.

Diagnostic x-rays include anteroposterior, oblique, and lateral views and should be made with the foot in full flexion.

Differential diagnosis

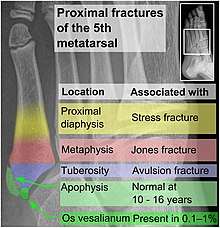

- Proximal diaphysis, typically stress fracture.[12][13]

- Metaphysis: Jones fracture[14]

-Tuberosity: Pseudo-Jones fracture[15] (avulsion fracture).[16]

Normal anatomy:

- Apophysis: Normal at 10 - 16 years.[17]

- Os vesalianum, an accessory bone.[18]

Other proximal fifth metatarsal fractures exist, although they are not as severe as a Jones fracture. If the fracture enters the intermetatarsal joint, it is a Jones fracture. If, however, it enters the tarsometatarsal joint, then it is an avulsion fracture caused by pull from the peroneus brevis. An avulsion fracture is sometimes called a Pseudo-Jones fracture or a Dancer's fracture.

This injury should be differentiated from the developmental "apophysis" which is the secondary ossification center of the metatarsal bone. It is normally occurring at this site in adolescents. Differentiation is possible by characteristics such as absence of sclerosis of the fractured edges (in acute cases) and orientation of the lucent line: transverse (at 90 degrees) to the metatarsal axis for the fracture (due to avulsion pull by the peroneus brevis muscle inserting at the proximal tip) – and parallel to the metatarsal axis in the case of the apophysis.

Treatment

Prognosis

For several reasons, a Jones fracture may not unite. The diaphyseal bone (zone II), where the fracture occurs, is an area of potentially poor blood supply, existing in a watershed area between two blood supplies. This may compromise healing. In addition, there are various tendons, including the peroneus brevis and fibularis tertius, and two small muscles attached to the bone. These may pull the fracture apart and prevent healing.

Zones I and III have been associated with relatively guaranteed union and this union has taken place with only limited restriction of activity combined with early immobilization. On the other hand, zone II has been associated with either delayed or non-union and, consequently, it has been generally agreed that fractures in this area should be considered for some form of internal immobilization, such as internal screw fixation.

These zones can be identified anatomically and on x-ray adding to the clinical usefulness of this classification.[19] It should be emphasized that surgical intervention is not, by itself, a guarantee of cure and has its own complication rate. Other reviews of the literature have concluded that conservative, non-operative, treatment is an acceptable option for the non-athlete.[20]

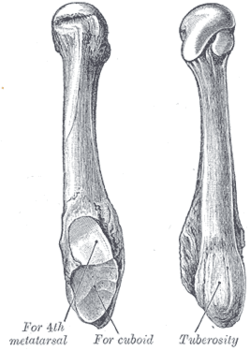

Anatomy of the fifth metatarsal.

Anatomy of the fifth metatarsal. 3 zone description

3 zone description 2 zone description

2 zone description

References

- "5th Metatarsal". Emergency Care Institute, New South Wales. 2017-09-19.

- Eltorai, Adam E. M.; Eberson, Craig P.; Daniels, Alan H. (2017). Orthopedic Surgery Clerkship: A Quick Reference Guide for Senior Medical Students. Springer. pp. 395–397. ISBN 9783319525679. Archived from the original on 2017-10-15.

- "Toe and Forefoot Fractures". OrthoInfo - AAOS. June 2016. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Valderrabano, Victor; Easley, Mark (2017). Foot and Ankle Sports Orthopaedics. Springer. p. 430. ISBN 9783319157351. Archived from the original on 2017-10-15.

- Bica, D; Sprouse, RA; Armen, J (1 February 2016). "Diagnosis and Management of Common Foot Fractures". American Family Physician. 93 (3): 183–91. PMID 26926612.

- Dähnert, Wolfgang (2011). Radiology Review Manual. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 96. ISBN 9781609139438. Archived from the original on 2017-10-15.

- Conaghan, Philip G.; O'Connor, Philip; Isenberg, David A. (2010). Musculoskeletal Imaging. OUP Oxford. p. 231. ISBN 9780191575273. Archived from the original on 2017-10-15.

- Joel A. DeLisa; Bruce M. Gans; Nicholas E. Walsh (2005). Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 881–. ISBN 978-0-7817-4130-9. Archived from the original on 2017-01-07.

- Mattu, Amal; Chanmugam, Arjun S.; Swadron, Stuart P.; Tibbles, Carrie; Woolridge, Dale; Marcucci, Lisa (2012). Avoiding Common Errors in the Emergency Department. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 790. ISBN 9781451152852. Archived from the original on 2017-10-16.

- Lee, Edward (2017). Pediatric Radiology: Practical Imaging Evaluation of Infants and Children. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. Chapter 24. ISBN 9781496380272. Archived from the original on 2017-10-15.

- Jones, Robert (Jun 1902). "I. Fracture of the Base of the Fifth Metatarsal Bone by Indirect Violence". Annals of Surgery. 35 (6): 697–700. PMC 1425723. PMID 17861128.

- Bica D, Sprouse RA, Armen J (2016). "Diagnosis and Management of Common Foot Fractures". Am Fam Physician. 93 (3): 183–91. PMID 26926612.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "5th Metatarsal". Emergency Care Institute, New South Wales. 2017-09-19.

- "Toe and Forefoot Fractures". OrthoInfo - AAOS. June 2016. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Robert Silbergleit. "Foot Fracture". Medscape.com. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- Robert Silbergleit. "Foot Fracture". Medscape.com. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- Deniz, G.; Kose, O.; Guneri, B.; Duygun, F. (2014). "Traction apophysitis of the fifth metatarsal base in a child: Iselin's disease". Case Reports. 2014 (may14 4): bcr2014204687–bcr2014204687. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-204687. ISSN 1757-790X.

- Nwawka, O. Kenechi; Hayashi, Daichi; Diaz, Luis E.; Goud, Ajay R.; Arndt, William F.; Roemer, Frank W.; Malguria, Nagina; Guermazi, Ali (2013). "Sesamoids and accessory ossicles of the foot: anatomical variability and related pathology". Insights into Imaging. 4 (5): 581–593. doi:10.1007/s13244-013-0277-1. ISSN 1869-4101. PMC 3781258.

- Polzer H, Polzer S, Mutschler W, Prall WC (Oct 2012). "Acute fractures to the proximal fifth metatarsal bone: development of classification and treatment recommendations based on the current evidence". Injury. 43 (10): 1626–32. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2012.03.010. PMID 22465516.

- Dean BJ, Kothari A, Uppal H, Kankate R (Aug 2012). "The jones fracture classification, management, outcome, and complications: a systematic review". Foot and Ankle Specialist. 5 (4): 256–9. doi:10.1177/1938640012444730. PMID 22547534.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to X-rays of Jones fractures. |

- Jones fracture, wheelessonline.com