Insect repellent

An insect repellent (also commonly called "bug spray") is a substance applied to skin, clothing, or other surfaces which discourages insects (and arthropods in general) from landing or climbing on that surface. Insect repellents help prevent and control the outbreak of insect-borne (and other arthropod-bourne) diseases such as malaria, Lyme disease, dengue fever, bubonic plague, river blindness and West Nile fever. Pest animals commonly serving as vectors for disease include insects such as flea, fly, and mosquito; and the arachnid tick .

Some insect repellents are insecticides (bug killers), but most simply discourage insects and send them flying or crawling away. Almost any might kill at a massive dose without reprieve, but classification as an insecticide implies death even at lower doses .

Common insect repellents

Common synthetic insect repellents

- Methyl anthranilate and other anthranilate-based insect repellents

- Benzaldehyde, for bees[1]

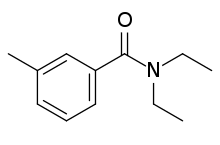

- DEET (N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide)

- Dimethyl carbate

- Dimethyl phthalate, not as common as it once was but still occasionally an active ingredient in commercial insect repellents

- Ethylhexanediol, also known as Rutgers 612 or "6-12 repellent," discontinued in the US in 1991 due to evidence of causing developmental defects in animals[2]

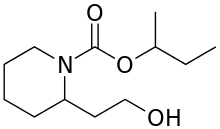

- Icaridin, also known as picaridin, Bayrepel, and KBR 3023

- Butopyronoxyl (trade name Indalone). Widely used in a "6-2-2" mixture (60% Dimethyl phthalate, 20% Indalone, 20% Ethylhexanediol) during the 1940s and 1950s before the commercial introduction of DEET

- Ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate (IR3535 or 3-[N-Butyl-N-acetyl]-aminopropionic acid, ethyl ester)

- Metofluthrin

- Permethrin is different in that it is actually a contact insecticide

- A more recent repellent being currently researched is SS220, which has been shown to provide significantly better protection than DEET

- Tricyclodecenyl allyl ether, a compound often found in synthetic perfumes[3][4]

Common natural insect repellents

- Beautyberry (Callicarpa) leaves

- Birch tree bark is traditionally made into tar. Combined with another oil (e.g., fish oil) at 1/2 dilution, it is then applied to the skin for repelling mosquitos[6]

- Bog Myrtle (Myrica Gale)

- Catnip oil whose active compound is Nepetalactone

- Citronella oil[7]

- Essential oil of the lemon eucalyptus (Corymbia citriodora) and its active compound p-menthane-3,8-diol (PMD)

- Neem oil

- Lemongrass

- Tea tree oil[8] from the leaves of Melaleuca alternifolia

- Tobacco

Repellent effectiveness

Synthetic repellents tend to be more effective and/or longer lasting than "natural" repellents.[9][10]

For protection against mosquito bites, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends DEET, picaridin (icaridin, KBR 3023), oil of lemon eucalyptus (para-menthane-diol or PMD), ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate and 2-undecanone with the caveat that higher percentages of the active ingredient provide longer protection.[11]

In 2015, Researchers at New Mexico State University tested 10 commercially available products for their effectiveness at repelling mosquitoes. On the mosquito Aedes aegypti, the vector of Zika virus, only one repellent that did not contain DEET had a strong effect for the duration of the 240 minutes test: a lemon eucalyptus oil repellent. All DEET-containing mosquito repellents were active.

In one comparative study from 2004, ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate was as effective or better than DEET in protection against Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes.[12] Other sources (official publications of the associations of German physicians[13] as well as of German druggists[14]) suggest the contrary and state DEET is still the most efficient substance available and the substance of choice for stays in malaria regions, while ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate has little effect. However, some plant-based repellents may provide effective relief as well.[9][10][15] Essential oil repellents can be short-lived in their effectiveness, since essential oils can evaporate completely.

A test of various insect repellents by an independent consumer organization found that repellents containing DEET or picaridin are more effective than repellents with "natural" active ingredients. All the synthetics gave almost 100% repellency for the first 2 hours, where the natural repellent products were most effective for the first 30 to 60 minutes, and required reapplication to be effective over several hours.[16]

Although highly toxic to cats, permethrin is recommended as protection against mosquitoes for clothing, gear, or bed nets.[17] In an earlier report, the CDC found oil of lemon eucalyptus to be more effective than other plant-based treatments, with a similar effectiveness to low concentrations of DEET.[18] However, a 2006 published study found in both cage and field studies that a product containing 40% oil of lemon eucalyptus was just as effective as products containing high concentrations of DEET.[19] Research has also found that neem oil is mosquito repellent for up to 12 hours.[15] Citronella oil's mosquito repellency has also been verified by research,[20] including effectiveness in repelling Aedes aegypti,[21] but requires reapplication after 30 to 60 minutes.

There are also products available based on sound production, particularly ultrasound (inaudibly high frequency sounds) which purport to be insect repellents. However, these electronic devices have been shown to be ineffective based on studies done by the United States Environmental Protection Agency and many universities.[22]

Repellent safety for humans

.svg.png)

Regarding safety with insect repellent use on children and pregnant women:

- Children may be at greater risk for adverse reactions to repellents, in part, because their exposure may be greater.

- Keep repellents out of the reach of children.

- Do not allow children to apply repellents to themselves.

- Use only small amounts of repellent on children.

- Do not apply repellents to the hands of young children because this may result in accidental eye contact or ingestion.

- Try to reduce the use of repellents by dressing children in long sleeves and long trousers tucked into boots or socks whenever possible. Use netting over strollers, playpens, etc.

- As with chemical exposures in general, pregnant women should take care to avoid exposures to repellents when practical, as the fetus may be vulnerable.

Some experts also recommend against applying chemicals such as DEET and sunscreen simultaneously since that would increase DEET penetration. Canadian researcher, Xiaochen Gu, a professor at the University of Manitoba’s faculty of Pharmacy who led a study about mosquitos, advises that DEET should be applied 30 or more minutes later. Gu also recommends insect repellent sprays instead of lotions which are rubbed into the skin "forcing molecules into the skin".[23]

Regardless of which repellent product used, it is recommended to read the label before use and carefully follow directions.[24] Usage instructions for repellents vary from country to country. Some insect repellents are not recommended for use on younger children.[11]

In the DEET Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED) the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reported 14 to 46 cases of potential DEET associated seizures, including 4 deaths. The EPA states: "... it does appear that some cases are likely related to DEET toxicity," but observed that with 30% of the US population using DEET, the likely seizure rate is only about one per 100 million users.[25]

The Pesticide Information Project of Cooperative Extension Offices of Cornell University states that, "Everglades National Park employees having extensive DEET exposure were more likely to have insomnia, mood disturbances and impaired cognitive function than were lesser exposed co-workers".[26]

The EPA states that citronella oil shows little or no toxicity and has been used as a topical insect repellent for 60 years. However, the EPA also states that citronella may irritate skin and cause dermatitis in certain individuals.[7] Canadian regulatory authorities concern with citronella based repellents is primarily based on data-gaps in toxicology, not on incidents.[27][28]

Within countries of the European Union, implementation of Regulation 98/8/EC,[29] commonly referred to as the Biocidal Products Directive, has severely limited the number and type of insect repellents available to European consumers. Only a small number of active ingredients have been supported by manufacturers in submitting dossiers to the EU Authorities.

In general, only formulations containing DEET, icaridin (sold under the trade name Saltidin and formerly known as Bayrepel or KBR3023), ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate (IR3535) and citriodiol (p-menthane-3,8-diol) are available. Most "natural" insect repellents such as citronella, neem oil, and herbal extracts are no longer permitted for sale as insect repellents in the EU due to their lack of effectiveness; this does not preclude them from being sold for other purposes, as long as the label does not indicate they are a biocide (insect repellent).

Repellent safety for the other creatures

A 2018 study found that Icaridin, in what the authors described as conservative exposure doses, is highly toxic to salamander larvae.[30] The LC50 standard was additionally found to be completely inadequate in the context of finding this result.[31]

Permethrin is highly toxic to cats but not to dogs or humans.[32]

Insect repellents from natural sources

There are many preparations from naturally occurring sources that have been used as a repellent to certain insects. Some of these act as insecticides while others are only repellent.

- Achillea alpina (mosquitos)

- alpha-terpinene (mosquitos)

- Basil[33]

- Sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum)

- Callicarpa americana (beautyberry)[34]

- Breadfruit (Insect repellent, including mosquitoes[35])

- Camphor (moths)

- Carvacrol (mosquitos)

- Castor oil (Ricinus communis) (mosquitos)[36]

- Catnip oil (Nepeta species) (nepetalactone against mosquitos)[37]

- Cedar oil (mosquitos, moths)[36]

- Celery extract (Apium graveolens) (mosquitos) In clinical testing an extract of celery was demonstrated to be at least equally effective to 25% DEET,[38] although the commercial availability of such an extract is not known.

- Cinnamon (leaf oil kills mosquito larvae)[39]

- Citronella oil (repels mosquitos)[36]

- Oil of cloves (mosquitos)[36]

- Eucalyptus oil (70%+ eucalyptol), (cineol is a synonym), mosquitos, flies, dust mites[40])

- Fennel oil (Foeniculum vulgare) (mosquitos)

- Garlic (Allium sativum) (Mosquito, rice weevil, wheat flour beetle)[41]

- Geranium oil (also known as Pelargonium graveolens)[36][42]

- Lavender (ineffective alone, but measurable effect in certain repellent mixtures)[43][44]

- Lemon eucalyptus (Corymbia citriodora) essential oil and its active ingredient p-menthane-3,8-diol (PMD)

- Lemongrass oil (Cymbopogon species) (mosquitos)[36]

- East-Indian lemon grass (Cymbopogon flexuosus)[45]

- Marigolds (Tagetes species)

- Marjoram (spider mites Tetranychus urticae and Eutetranychus orientalis)[46]

- Mint (menthol is active chemical.) (Mentha sp.)

- Neem oil (Azadirachta indica) (Repels or kills mosquitos, their larvae and a plethora of other insects including those in agriculture)

- Oleic acid, repels bees and ants by simulating the "smell of death" produced by their decomposing corpses.

- Pennyroyal (Mentha pulegium) (mosquitos,[40] fleas,[47]) but very toxic to pets[47]

- Peppermint (Mentha x piperita) (mosquitos)[48]

- Pyrethrum (from Chrysanthemum species, particularly C. cinerariifolium and C. coccineum)

- Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis)[46] (mosquitos)[36]

- Spanish Flag (Lantana camara) (against Tea Mosquito Bug, Helopeltis theivora)[49]

- Tea tree oil[8] from the leaves of Melaleuca alternifolia

- Thyme (Thymus species) (mosquitos)

- Yellow nightshade (Solanum villosum), berry juice (against Stegomyia aegypti mosquitos)[50]

- Andrographis paniculata extracts (mosquito)[51]

Less effective methods

Some old studies suggested that the ingestion of large doses of thiamine could be effective as an oral insect repellent against mosquito bites. However, there is now conclusive evidence that thiamin has no efficacy against mosquito bites.[52][53][54][55] Some claim that plants like wormwood or sagewort, lemon balm, lemon grass, lemon thyme and the mosquito plant (Pelargonium) will act against mosquitoes. However, scientists have determined that these plants are "effective" for a limited time only when the leaves are crushed and applied directly to the skin.[56]

There are several, widespread, unproven theories about mosquito control, such as the assertion that vitamin B, in particular B1 (thiamine), garlic, ultrasonic devices or incense can be used to repel or control mosquitoes.[53][57] Moreover, manufacturers of "mosquito repelling" ultrasonic devices have been found to be fraudulent,[58] and their devices were deemed "useless" according to a review of scientific studies.[59]

See also

- Fly spray (insecticide)

- Mosquito coil

- Mosquito net

- Pest control

- RID Insect Repellent

- Slug tape

- VUAA1

References

- Evans, Elizabeth; Butler, Carol (2010-02-09). Why Do Bees Buzz?: Why Do Bees Buzz? Fascinating Answers to Questions about Bees. Rutgers University Press. pp. 177–178. ISBN 9780813549200.

- Brown, Maryland Extension Service leaflet 10

- Insect Repellents - Patent 6660288

- Detailed patent information

- Comparisons explanatory text in the display: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Oil_Jar_in_cow_horn_for_mosquito-repelling_pitch_oil.JPG

- Birch bark used as mosquito repellent

- "Citronella (Oil of Citronella) (021901) Fact Sheet". United States Environmental Protection Agency. 16 February 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- U.S. Patent 5,738,863

- M. S. Fradin; J. F. Day (2002). "Comparative Efficacy of Insect Repellents against Mosquito Bites". N Engl J Med. 347 (1): 13–18. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa011699. PMID 12097535.

- Collins, D.A.; Brady, J.N.; Curtis, C.F. (1993). "Assessment of the efficacy of Quwenling as a Mosquito repellent". Phytotherapy Research. 7 (1): 17–20. doi:10.1002/ptr.2650070106.

- "Updated Information regarding Insect Repellents". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 14 August 2017.

- Cilek JE, Petersen JL, Hallmon CE (2004). "Comparative efficacy of IR3535 and deet as repellents against adult Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus". J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 20 (3): 299–304. PMID 15532931.

- "Insektenschutz: Wie man das Stichrisiko senkt". 2013-07-22.

- "Repellentien und Insektizide: Erfolgreich gegen den Insektenangriff".

- Mishra AK, Singh N, Sharma VP (1995). "Use of neem oil as a mosquito repellent in tribal villages of mandla district, madhya pradesh". Indian J Malariol. 32 (3): 99–103. PMID 8936291.

- "Test: Mosquito Repellents, The Verdict" Choice, The Australian Consumers Association

- "Protection against Mosquitoes, Ticks, & Other Arthropods", U.S. Centers for Disease Control

- "Insect Repellent Use and Safety". West Nile Virus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 12 January 2007.

- Carroll SP, Loye J, 2006, Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 22(3):507-514, 510

- Jeong-Kyu KIM, Chang-Soo KANG, Jong-Kwon LEE, Young-Ran KIM, Hye-Yun HAN, Hwa Kyung YUN, Evaluation of Repellency Effect of Two Natural Aroma Mosquito Repellent Compounds, Citronella and Citronellal, Entomological Research 35 (2), 117–120, 2005

- Ibrahim Jantan, and Zaridah Mohd. Zaki, Development of environment-friendly insect repellents from the leaf oils of selected Malaysian plants, ASEAN Review of Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation (ARBEC), May 1998.

- "Mosquito repellents that emit high-pitched sounds don't prevent bites" (Press release). Eurekalert!. April 17, 2007.

- "How to choose the best bug repellent". Best Health. Reader's Digest Association, Inc. January 2000. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

‘Anything intended for topical use only shouldn’t be going into the body,’ says Xiaochen Gu, a professor at the University of Manitoba’s faculty of pharmacy, who led the study.

- "Health Advisory: Tick and Insect Repellents", Information factsheet, Department of Health, New York State

- "Reregistration Eligibility Decision: DEET." U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Prevention, Pesticides, and Toxic Substances. September 1998. pp39-40 Archived 2012-10-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Deet

- Re-evaluation of Citronella Oil and Related Active Compounds for Use as Personal Insect Repellents (PDF). Responsible Pesticide Use. Pest Management Regulatory Agency (Canada). 17 September 2004. ISBN 978-0-662-38012-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-07-11.

- "So Then: Who’s Afraid of Citronella Oil? Update!" Archived 2007-10-15 at the Wayback Machine Cropwatch Newsletter Vol 2, Issue 1, No. 1

- "Directive 98/8/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 February 1998 concerning the placing of biocidal products on the market". Official Journal of the European Communities. 16 February 1998. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- Almeida, Rafael; Han, Barbara; Reisinger, Alexander; Kagemann, Catherine; Rosi, Emma (1 October 2018). "High mortality in aquatic predators of mosquito larvae caused by exposure to insect repellent". Biology Letters. 14 (10): 20180526. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2018.0526. PMC 6227861. PMID 30381452.

- "Widely used mosquito repellent proves lethal to larval salamanders". Science News. ScienceDaily. Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. 31 October 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- Roberts, Catherine (22 October 2018). "Should You Use Natural Tick Prevention for Your Dog or Cat?". Consumer Reports. Consumer Reports Inc. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- Taverne, Janice (2001). "Malaria on the Web and the mosquito-repellent properties of basil". Trends in Parasitology. 17 (6): 299–300. doi:10.1016/S1471-4922(01)01978-X.

- "A Granddad's Advice May Help Thwart Mosquitoes". www.sciencedaily.com. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- A. Maxwell P. Jones; Jerome A. Klun; Charles L. Cantrell; Diane Ragone; Kamlesh R. Chauhan; Paula N. Brown; Susan J. Murch (2012). "Isolation and Identification of Mosquito (Aedes aegypti) Biting Deterrent Fatty Acids from Male Inflorescences of Breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson) Fosberg)". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 60 (15): 3867–3873. doi:10.1021/jf300101w. PMID 22420541.

- "Natural Mosquito Repellents". chemistry.about.com. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- "Catnip Repels Mosquitoes More Effectively Than DEET". www.sciencedaily.com. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- Tuetun, B.; Choochote, W.; Pongpaibul, Y.; Junkum, A.; Kanjanapothi, D.; Chaithong, U.; Jitpakdi, A.; Riyong, D.; Wannasan, A.; Pitasawat, B. (2008). "Field evaluation of G10, a celery (Apium graveolens)-based topical repellent, against mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in Chiang Mai province, northern Thailand". Parasitology Research. 104 (3): 515–521. doi:10.1007/s00436-008-1224-9. PMID 18853188.

- "Cinnamon Oil Kills Mosquitoes". www.sciencedaily.com. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- "Natural Insect and Rodent Repellents - Quick & Simple". www.quickandsimple.com. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- Rahman, G. K. M. M.; N. Motoyama (1998). "Identification of the active components of garlic causing repellent effect against the rice weevil and the wheat flour beetle". Nihon Oyo Doubutsu Konchu Gakkai Taikai Koen Youshi. 42: 211. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- Botha, B. M.; C. M. McCrindle (2000). "An appropriate method for extracting the insect repellent citronellol from an indigenous plant (Pelargonium graveolens L'Her) for potential use by resource-limited animal owners". Retrieved 30 May 2009.

- Jaenson, Thomas G. T.; et al. (2006). "Repellency of Oils of Lemon Eucalyptus, Geranium, and Lavender and the Mosquito Repellent MyggA Natural to Ixodes ricinus (Acari: Ixodidae) in the Laboratory and Field". Journal of Medical Entomology. 43 (4): 731–736. doi:10.1603/0022-2585(2006)43[731:ROOOLE]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-2585.

- Cook, Samantha M.; et al. (2007). "Responses of Phradis parasitoids to volatiles of lavender, Lavendula angustifolia – a possible repellent for their host, Meligethes aeneus". BioControl. 52 (5): 591–598. doi:10.1007/s10526-006-9057-x.

- Oyedele, A. O.; et al. (2002). "Formulation of an effective mosquito-repellent topical product from Lemongrass oil". Phytomedicine. 9 (3): 259–262. doi:10.1078/0944-7113-00120. PMID 12046869.

- Momen, F. M.; et al. (2001). "Repellent and Oviposition-Deterring Activity of Rosemary and Sweet Marjoram on the Spider Mites Tetranychus urticae and Eutetranychus orientalis (Acari: Tetranychidae)". Acta Phytopathologica et Entomologica Hungarica. 36 (1–2): 155–164. doi:10.1556/APhyt.36.2001.1-2.18.

- "Warnings". bitsandbrew.com. Archived from the original on April 23, 2008. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- Ansari, M. A.; et al. (2000). "Larvicidal and mosquito repellent action of peppermint (Mentha piperita) oil". Bioresource Technology. 71 (3): 267–271. doi:10.1016/S0960-8524(99)00079-6.

- Deka, M. K.; et al. "Antifeedant and Repellent Effects of Pongam (Pongamia Pinnata) and Wild Sage (Lantana Camara) on Tea Mosquito Bug (Helopeltis Theivora)". Indian Journal of Agricultural Science. 68 (5): 274. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- "Common Weed, Ayurvedic Nightshade, Deadly For Dengue Mosquito". www.sciencedaily.com. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- Govindarajan M., Sivakumar R. " Adulticidal and repellent properties of indigenous plant extracts against Culex quinquefasciatus and Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasitol Res. 2011 Oct 20.

- BMJ Clinical Evidence

- Ives A.R.; Paskewitz, S.M. (June 2005). "Testing vitamin B as a home remedy against mosquitoes". J. Am. Mosq. Control. Assoc. 21 (2): 213–217. doi:10.2987/8756-971X(2005)21[213:TVBAAH]2.0.CO;2. PMID 16033124.

- Khan AA, Maibach HI, Strauss WG, Fenley WR (2005). "Vitamin B1 is not a systemic mosquito repellent in man". Trans. St. Johns Hosp. Dermatol. Soc. 55 (1): 99–102. PMID 4389912.

- Strauss WG, Maibach HI, Khan AA (1968). "Drugs and disease as mosquito repellents in man". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 17 (3): 461–464. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1968.17.461. PMID 4385133.

- Medscape: Medscape Access

- "Insect Repellents". DermNet NZ. 5 July 2010. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- Lentek International-08/28/02

- Enayati AA, Hemingway J, Garner P (2007). "Electronic mosquito repellents for preventing mosquito bites and malaria infection" (PDF). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 18 (2): CD005434. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005434.pub2. PMC 6532582. PMID 17443590.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to insect repellents. |

- 2011 review of studies of plant-based mosquito repellents - NIH

- Aphid repellents

- Choosing and Using Insect Repellents - National Pesticide Information Center

- Jeanie Lerche Davis (2003). "Best Insect Repellent for Mosquitoes: Bug Experts Rate Products to Keep West Nile Virus at Bay". WebMD.

- "CDC Adopts New Repellent Guidance" (Press release). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 28 April 2005. Archived from the original on 2008-04-30.

- Department of Health, New York State. "Health Advisory: Tick and Insect Repellents".

- Plant parts with Insect-repellent Activity from the chemical Borneol (Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases)

- Mosquito repellents; Florida U

- Insect repellent active ingredients recommended by the CDC