Iliotibial band syndrome

Ilitotibial Band Syndrome (ITBS) is the second most common knee injury caused by inflammation located on the lateral aspect of the knee due to friction between the iliotibial band and the lateral epicondyle of the femur.[2] Pain is felt most commonly on the lateral aspect of the knee and is most intensive at 30 degrees of knee flexion.[2] Risk factors in women include increased hip adduction, knee internal rotation.[2][3] Risk factors seen in men are increased hip internal rotation and knee adduction.[2] ITB syndrome is most associated with long distance running, cycling, weight-lifting, and with military training.[4][5]

| Iliotibial band syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Iliotibial band friction syndrome (ITBFS)[1] |

| |

| Specialty | Sports medicine, orthopedics |

Signs and symptoms

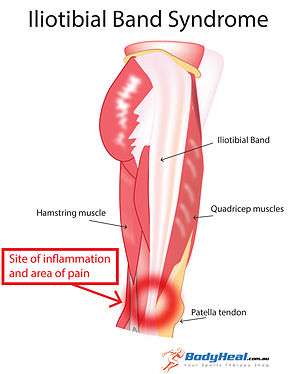

ITBS symptoms range from a stinging sensation just above the knee and outside of the knee (lateral side of the knee) joint, to swelling or thickening of the tissue in the area where the band moves over the femur. The stinging sensation just above the knee joint is felt on the outside of the knee or along the entire length of the iliotibial band. Pain may not occur immediately during activity, but may intensify over time. Pain is most commonly felt when the foot strikes the ground, and pain might persist after activity. Pain may also be present above and below the knee, where the ITB attaches to the tibia.

Causes

ITBS can result from one or more of the following: training habits, anatomical abnormalities, or muscular imbalances:

|

Training habits

|

Abnormalities in leg/feet anatomy

Muscle imbalance

|

Anatomical mechanism

Iliotibial band syndrome is one of the leading causes of lateral knee pain in runners. The iliotibial band is a thick band of fascia on the lateral aspect of the knee, extending from the outside of the pelvis, over the hip and knee, and inserting just below the knee. The band is crucial to stabilizing the knee during running, as it moves from behind the femur to the front of the femur during activity. The continual rubbing of the band over the lateral femoral epicondyle, combined with the repeated flexion and extension of the knee during running may cause the area to become inflamed.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of iliotibial band syndrome is based on history and physical exam findings, including tenderness at the lateral femoral epicondyle, where the iliotibial band passes over the bone.

Treatment

Conservative Treatments

While ITBS pain can be acute, the iliotibial band can be rested, iced, compressed and elevated (RICE) to reduce pain and inflammation, followed by stretching.[7] Utilization of corticosteroid injections and the use of anti-inflammatory medication on the painful area are possible treatments for ITB syndrome. Corticosteroid injections have been shown to decrease running pains significantly 7 days after the initial treatment.[8] Similar results can be found with the use of anti-inflammatory medication, analgesic/anti-inflammatory medication, specifically.[8] Other non-invasive treatments include things such as, flexibility and strength training, neuromuscular/gait training, manual therapy, training volume reduction, or changes in running shoe.[2][8][3][9] Muscular training of the gluteus maximus and hip external rotators is stressed highly as those muscles are associated with many of the risk factors of ITBS.[2] For runners specifically, neuromuscular/gait training may be needed for success in muscular training interventions to ensure that those trained muscles are used properly in the mechanics of running.[2] Strength training alone will not result in decrease in pain due to ITBS, however, gait training, on its own can result in running form modification that reduces the prevalence of risk factors.[3]

Epidemiology

Occupation

Significant association between the diagnosis of ITBS and occupational background of the patients has been thoroughly determined. Occupations that require extensive use of iliotibial band are more susceptible to develop ITB due to continuum of their iliotibial band repeatedly abrading against lateral epicondyle prominence, thereby inducing inflammatory response. Professional or amateur runners are at high clinical risk of ITBS in which shows particularly greater risk in long-distance. Study suggests ITBS alone makes up 12% of all running-related injuries and 1.6% to 12% of runners are afflicted by ITBS.[10]

The relationship between ITBS and mortality/morbidity is claimed to be absent. A study showed that coordination variability did not vary significantly between runners with no injury and runners with ITBS.[11] This result elucidates that the runner’s ability to coordinate themselves toward direction of their intention (motor coordination) is not, or very minorly affected by the pain of ITBS.

Additionally, military trainee in marine boot camps displayed high incidence rate of ITBS. Varying incidence rate of 5.3% - 22% in basic training was reported in a case study. A report from the U.S. Marine Corps announces that running/overuse-related injuries accounted for 12%> of all injuries.[12]

In contrast, studies suggested antithesis of conventional perception that racial, gender or age difference manifests in different incidence rate of ITBS diagnosis. No meaningful statistical data successfully provides significant correlation between ITBS and gender, age, or race. Although, there had been a claim that females are more prone to ITBS due to their anatomical difference in pelvis and lower extremity. Males with larger lateral epicondyle prominence may also be more susceptible to ITBS.[13] Higher incidence rate of ITBS has been reported at age of 15-50, in which generally includes most of active athletes.

Other professions that had noticeable association with ITBS include cyclists, heavy weightlifters, et cetera. One observational study discovered 24% of 254 cyclists were diagnosed with ITBS within 6 years.[14] Another study provided data that shows more than half (50%) of professional cyclists complain of knee pain.[15]

References

- Ellis, R; Hing, W; Reid, D (August 2007). "Iliotibial band friction syndrome—A systematic review". Manual Therapy. 12 (3): 200–8. doi:10.1016/j.math.2006.08.004. PMID 17208506.

- Baker, Rober L.; Fredericson, Micheal (2016). "ClinicalKey". www.clinicalkey.com. Retrieved 2019-11-17.

- Neal, Bradley (2016). "Iliotibial Band Syndrome: A Narrative Review". Co-Kinetic journal. 67: 16–20 – via EBSCO host.

- "Iliotibial Band Syndrome: Background, Epidemiology, Functional Anatomy". 2019-11-10. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hadeed, Andrew; Tapscott, David C. (2019), "Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31194342, retrieved 2019-11-17

- Farrell, Kevin C.; Reisinger, Kim D.; Tillman, Mark D. (March 2003). "Force and repetition in cycling: possible implications for iliotibial band friction syndrome". The Knee. 10 (1): 103–109. doi:10.1016/S0968-0160(02)00090-X.

- Barber, F. Alan; Sutker, Allan N. (August 1992). "Iliotibial Band Syndrome". Sports Medicine. 14 (2): 144–148. doi:10.2165/00007256-199214020-00005. PMID 1509227.

- Beals, Corey; Flanigan, David (2013). "A Review of Treatments for Iliotibial Band Syndrome in the Athletic Population". Journal of Sports Medicine. 2013. doi:10.1155/2013/367169. ISSN 2356-7651. PMC 4590904. PMID 26464876.

- Weckström, Kristoffer; Söderström, Johan (2016). "Radial extracorporeal shockwave therapy compared with manual therapy in runners with iliotibial band syndrome". Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 29: 161–170 – via EBSCOhost.

- Richards, David P.; Alan Barber, F.; Troop, Randal L. (March 2003). "Iliotibial band Z-lengthening". Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 19 (3): 326–329. doi:10.1053/jars.2003.50081. ISSN 0749-8063.

- Hafer, Jocelyn F.; Brown, Allison M.; Boyer, Katherine A. (August 2017). "Exertion and pain do not alter coordination variability in runners with iliotibial band syndrome". Clinical Biomechanics. 47: 73–78. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2017.06.006. ISSN 0268-0033.

- Jensen, Andrew E; Laird, Melissa; Jameson, Jason T; Kelly, Karen R (2019-03-01). "Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Injuries Sustained During Marine Corps Recruit Training". Military Medicine. 184 (Supplement_1): 511–520. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy387. ISSN 0026-4075.

- Everhart, Joshua S.; Kirven, James C.; Higgins, John; Hair, Andrew; Chaudhari, Ajit A.M.W.; Flanigan, David C. (August 2019). "The relationship between lateral epicondyle morphology and iliotibial band friction syndrome: A matched case–control study". The Knee: S0968016018306847. doi:10.1016/j.knee.2019.07.015.

- Farrell, Kevin C.; Reisinger, Kim D.; Tillman, Mark D. (March 2003). "Force and repetition in cycling: possible implications for iliotibial band friction syndrome". The Knee. 10 (1): 103–109. doi:10.1016/s0968-0160(02)00090-x. ISSN 0968-0160.

- Holmes, James C.; Pruitt, Andrew L.; Whalen, Nina J. (May 1993). "Iliotibial band syndrome in cyclists". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 21 (3): 419–424. doi:10.1177/036354659302100316. ISSN 0363-5465.

Further reading

van der Worp, Maarten P.; van der Horst, Nick; de Wijer, Anton; Backx, Frank J. G.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, Maria W. G. (23 December 2012). "Iliotibial Band Syndrome in Runners". Sports Medicine. 42 (11): 969–992. doi:10.1007/BF03262306.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |