Iliofemoral ligament

The iliofemoral ligament is a ligament of the hip joint which extends from the ilium to the femur in front of the joint. It is also referred to as the Y-ligament (see below). the ligament of Bigelow, the ligament of Bertin and any combinations of these names.

| Iliofemoral | |

|---|---|

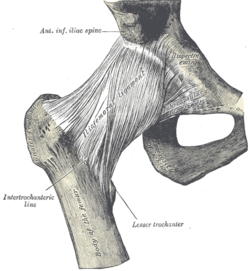

Right hip-joint from the front. (Iliofemoral ligament visible at center.) | |

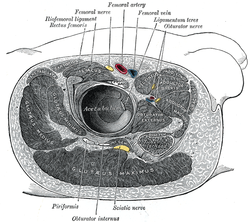

Structures surrounding right hip-joint. (Iliofemoral ligament labeled at upper left.) | |

| Details | |

| From | ilium (anterior inferior iliac spine) |

| To | femur (intertrochanteric line) |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | ligamentum iliofemorale |

| TA | A03.6.07.003 |

| FMA | 42993 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

With a tensile strength exceeding 350 kg (772 lbs),[1] the iliofemoral ligament is not only stronger than the two other ligaments of the hip joint, the ischiofemoral and the pubofemoral, but also the strongest ligament in the human body and as such is an important constraint to the hip joint.[2]

Structure

Arising from the anterior inferior iliac spine and the rim of the acetabulum, the iliofemoral ligament spreads obliquely downwards and laterally to the intertrochanteric line on the anterior side of the femoral head. It is divided into two parts or bands which act differently: the transverse part above, is strong and runs parallel to the axis of the femoral neck. The descending part below, is weaker and runs parallel to the femoral shaft. As the lateral portion is twisted like a screw, the two parts together take the form of an inverted Y.[3]

It is intimately connected with the joint capsule, and serves to strengthen the joint by resisting hyperextension. Its upper band is sometimes named the iliotrochanteric ligament. Between the two bands is a thinner part of the capsule. In some cases there is no division, and the ligament spreads out into a flat triangular band which is attached to the whole length of the intertrochanteric line.

Function

In a standing posture, when the pelvis is tilted posteriorly, the ligament is twisted and tense, which prevents the trunk from falling backwards and the posture is maintained without the need for muscular activity. In this position the ligament also keeps the femoral head pressed into the acetabulum.[3]

As the hip flexes, the tension in the ligament is reduced and the amount of possible rotations in the hip joint is increased, which permits the pelvis to tilt backwards into its sitting angle. Lateral rotation and adduction in the hip joint is controlled by the strong transversal part, while the descending part limits medial rotation.[3]

Turnout used in the classical ballet style requires a great deal of flexibility in this ligament. As does the front split where the rear leg is hyper-extended at the hip. Many externally rotate the rear leg while doing a front split, this external rotation when the hip is not flexed stretches the ligament even more. This "martial arts split" is distinguished by the rear knee pointing outward sideways (usually the foot along with it) rather than pointing straight down with the patella facing the floor, in a pure extension front split.

Additional images

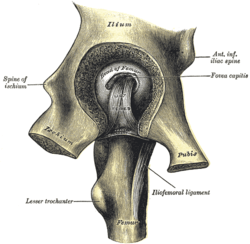

Left hip-joint, opened by removing the floor of the acetabulum from within the pelvis.

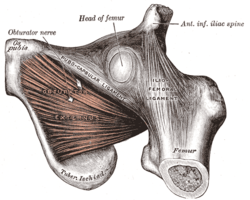

Left hip-joint, opened by removing the floor of the acetabulum from within the pelvis. The Obturator externus.

The Obturator externus. A front split requires mobility in the ligament to adequately extend the rear hip joint.

A front split requires mobility in the ligament to adequately extend the rear hip joint. Front oversplits require even more mobility to attain proper hip hyperextension.

Front oversplits require even more mobility to attain proper hip hyperextension.

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 335 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- Platzer, Werner (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol 1: Locomotor system (5th ed.). Thieme. p. 198. ISBN 3-13-533305-1.

- Thieme Atlas of Anatomy. Thieme. 2006. p. 380. ISBN 3131420812.

- Platzer, Werner (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol 1: Locomotor system (5th ed.). Thieme. p. 200. ISBN 3-13-533305-1.

External links

- lljoints at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (hipjointanterior)

- hip/hip%20ligaments/ligaments3 at the Dartmouth Medical School's Department of Anatomy