Ichthyophthirius multifiliis

Ichthyophthirius multifiliis is an ectoparasite of freshwater fish which causes a disease commonly known as white spot disease, or Ich.[1] Ich is one of the most common and persistent diseases in fish. It appears on the body, fins and gills of fish as white nodules of up to 1 mm, that look like white grains of salt. Each white spot is an encysted parasite.[2] It is easily introduced into a fish pond or home aquarium by new fish or equipment which has been moved from one fish-holding unit or pond to another. When the organism gets into a large fish culture facility, it is difficult to control due to its fast reproductive cycle and its unique life stages. If not controlled, there is a 100% mortality rate of fish. With careful treatment, the disease can be controlled but the cost is high in terms of lost fish, labor, and cost of chemicals.[3]

| Ichthyophthirius multifiliis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cichlid showing the white spots characteristic of ich | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| (unranked): | SAR |

| (unranked): | |

| Phylum: | Ciliophora |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | Ichthyophthiriidae |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | I. multifiliis |

| Binomial name | |

| Ichthyophthirius multifiliis Fouquet, 1876 | |

The protozoa damages the gills and skin as it enters the tissues, leading to ulceration and loss of skin. Severe infections rapidly lead to loss of condition and death. Damage to the gills reduces the respiratory efficiency of the fish, reducing its oxygen intake from the water. This causes the fish to become less tolerant to low oxygen concentrations in the water.[4]

Life stages

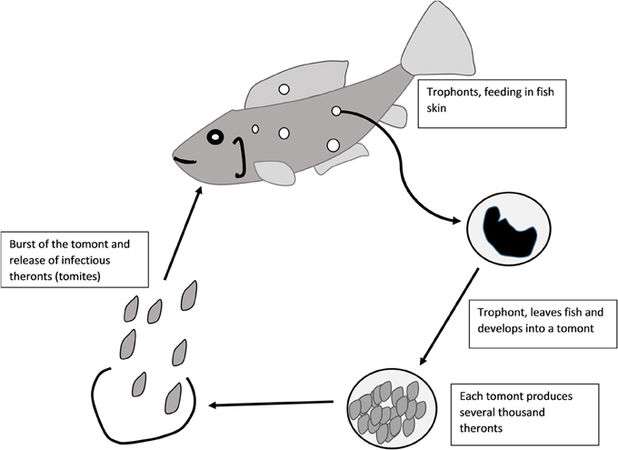

Simplified scheme of the life cycle of the fish parasite Ichthyophthirius multifiliis

Simplified scheme of the life cycle of the fish parasite Ichthyophthirius multifiliis

The ich protozoan goes through these life stages:[1]

- Feeding stage: The ich trophont (a protozoan in active stage of life) feeds in a nodule formed in the skin or gill epithelium.[1]

- After it feeds within the skin or gills, the trophont falls off and enters an encapsulated dividing stage (tomont). The tomont adheres to plants, nets, gravel or other ornamental objects in the aquarium.[1]

- The tomont divides up to 10 times by binary fission, producing infectious theronts, thus dividing rapidly and attacking the fish.[1]

This life cycle is highly dependent on water temperature, and the entire life cycle takes from approximately 7 days at 25 °C (77 °F) to 8 weeks at 6 °C (43 °F).

Disease

Signs and symptoms

Typical behaviors of clinically infected fish include:

- Anorexia (loss of appetite, refusing all food, with consequential wasting)

- Rapid breathing

- Hiding abnormally

- Not schooling (in schooling fish)

- Resting on the bottom

- Flashing (rubbing and scratching against objects)

- Upside-down swimming near the surface

A sub-clinically infected fish will not show any of these signs. For example, a healthy fish with a newly attached trophont will not yet have clinical disease. The trophont is not visible to the naked eye until it has fed on the fish and grown to one or two millimeters. A trophont attached to the gills is hard to see. A sub-clinically infected fish may initially only have a single trophont.

Skin

Visible Ich lesions are usually seen as one or several characteristic white spots on the body or fins of the fish. The white spots are single cells called trophonts, which feed on the tissues of the host and may grow to 1 mm in diameter. A smear should show ciliates if white spot is present.

Gills

Gill infection may cause breathing at the surface and fast respiration. Gill examination may reveal numbers of white spots or wet mount of a gill from a biopsy may reveal the trophonts. The fishes' breathing can slow, causing them to rest on the sand or gravel.[5]

Pathology

How Ich kills fish is not exactly known, however observations give possible explanations. When Ich infects the gills, the outer layer of the gills become inflamed, restricting the flow of oxygen to the blood. The respiratory folds, lamellae, become deformed, further reducing the transfer of oxygen. The sheer numbers of Ich organisms attached to the gills can mechanically block oxygen transfer.[6]

The outer lay of gill cells may separate and result in loss of fluids, making the fish struggle to regulate water concentration in the body. Secondary bacterial and fungal infections are common when the fish is impaired from the parasite.[6]

Predisposing factors

There is no dormant stage in the life cycle. However, any factor that reduces immunity, such as changes in water temperature and quality, accelerate an outbreak of Ich in a sub-clinically infected fish. Ammonia, nitrite, or high levels of nitrate in water do not in themselves cause clinical cases of Ich. However, poor water quality stresses fish, which allows an outbreak to spread rapidly and increases mortality rates.[7]

Other abiotic factors can increase both fish and tadpole susceptibility to Ich. These factors include decreased temperature, predatory cues (crowding or fighting), and increased levels of UV-B radiation.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of "Ich" can easily be confirmed by microscopic examination of skin and gills. Remove several "white spots" from an infected fish, then mount them on a microscope slide with a few drops of water and cover with glass. The mature parasite is large and dark (due to thick cilia covering the entire cell). It has a horseshoe-shaped nucleus, which is sometimes visible under 100x magnification. The adult parasite moves slowly by tumbling. The immature forms [theronts] are smaller, translucent, and move quickly.[3]

Treatment

Any treatment method must take into account the species of fish (some will not tolerate certain medications), how many of the fish are affected, and the size and kind of environment. Temperature affects how quickly the parasites multiply, so increasing the temperature can force them through their life cycle more quickly, allowing treatments to target Ichthyophthirius in its theront stage. Also, higher temperatures around 86 °F (30 °C) can prevent tomont replication.[8]

If Ich is detected before it becomes too serious, a number of different treatments can be applied.[9] The first line of treatment for severe outbreak is usually formalin or malachite green, or a combination of the two. Copper, methylene blue, and baths of potassium permanganate, quinine hydrochloride, and sodium chloride (aquarium salt) have also been used but do not appear to offer an advantage over the more readily available formalin and malachite green products.[8]

Total fish removal

Theronts, the motile and fish-infecting stage of the Ich life cycle, exit from the tomont that burst at the bottom of the tank. Without fish to re-attach to, however, theronts will die within 48 hours of exiting their tomont. Thus, an effective way to clear a tank from Ich is to remove all of the fish for a certain amount of time. At 80 degrees Fahrenheit, Ich theronts will die at 2 days in the absence of fish, and just to be absolutely sure, some recommend keeping the tank empty of fish and at 80 degrees for 4 days (96 hours).[8] This solution may be helpful when there are either very few fish in the tank or when tank capacity is too large to easily treat the volume of water.

Heat treatment

Heat treatment can be highly effective, and it can be combined with other treatments. However, it can only be used on fish that can tolerate high water temperatures, and is unsuitable for cold water fish like koi and goldfish, but even in those cases, a higher water temperature will accelerate the life-cycle of the parasite, allowing other treatments to take effect sooner.

Salt

Aquarium salt at 3-5 grams/liter for two weeks can be used to treat mild infections of Ich. Be aware that some soft water species and some catfishes can be more sensitive to salt. Contrary to some recommendations, do not use as a preventative indefinitely. Continued use of salt could allow Ich to developed resistance to salt at levels that are unsafe for the fish.[10]

Chemical treatments

Chemical treatments include formalin, malachite green, methylene blue, chelated copper, copper sulfate, potassium permanganate, quinine and tosylchloramide sodium. There are also many proprietary treatments available for the treatment of white spot, and the related Oodinium (velvet disease). Chemical treatment is only effective against free-swimming juvenile parasites [theronts].[3] All treatments target the free-living theronts, which only survive about two to three days in the absence of a host fish.

Formalin is a common and effective treatment for this parasite. However, somethings need to be considered prior to using in an aquarium. First, formalin is a solution of formaldehyde gas dissolved in water, therefore use caution when adding it to the aquarium to avoid inhalation and skin and eye contact. Also, formalin removes oxygen from the water and can damage the gills of the fish, so adding an air stone during treatment is highly recommended. Finally, special care is required when treating fish in soft water because formalin is more toxic in soft water.[10]

Copper is another common and effective treatment for this parasite. However, three facts are essential to know prior to using in an aquarium. It is very easy to overdose with copper. The recommended dosage is 0.15-0.3 mg/L and the concentration should never exceed 0.4 mg/L. Also, copper is noticeably more toxic to fish in soft water than in hard water. Lastly, copper is highly toxic to common aquarium invertebrates like shrimp and snails. The combination of these facts makes it a poor choice for the average aquarium hobbyist.[10]

Methylene blue is commonly available for aquarium stores. Despite its effectiveness against external protozoan infections, it is now considered an outdated medication due to its effects on beneficial bacteria, causing toxic ammonia and nitrite levels.[10]

Prognosis

When Ich is diagnosed early, effective treatment is used, and stresses are minimized, mortality rates can be low. However, if the infection is at an advanced stage, treatment protocols are not followed, and the fish are stressed, higher death rates will occur. When a fish has had Ich eradicated, it may develop partial resistance to reinfection.[6]

Partially treated fish may initially harbor low numbers of unseen trophonts, often in the gills. This sub-clinical carrier will cause another outbreak weeks later, most likely when stresses occur, or uninfected fish are introduced to the aquarium.[6]

Prevention

In preventing infection, priority should be given to avoid introducing the parasite in the first place.[11]

New tropical fish should be quarantined for at least four weeks and cold-water fish for eight weeks. Also, washing your hands before and after maintenance of each tank and using separate equipment will reduce the chances of spreading the parasite between tanks.[10]

New plants should be washed in lukewarm water and quarantined for several days. During quarantine, plants can be treated with a plant disinfectant or a mild broad-spectrum anti-parasitic remedy. Alternatively, the plants can be dipped in a weak (pale pink) solution of potassium permanganate for several minutes, rinsed with running water and added to the aquarium.[10]

Prevention of the disease by vaccination is not possible, although several studies identified potential vaccine candidate proteins, i.e. i-antigens, of the parasite.[12][13]

Fish that survive an Ich infection may develop at least a partial immunity, which paralyzes theronts that attempt to infect it.[13]

See also

- Marine ich, a similar disease of marine fishes.

References

- Noga, Edward J. (2000). Fish disease: diagnosis and treatment. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 95–97. ISBN 978-0-8138-2558-8.

- Ostrow, Marshall E. (2003). Goldfish. Barron's Educational Series. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-7641-1986-6.

- "Ichthyophthirius multifiliis (White Spot) Infections in Fish" (PDF). Aces.edu. Retrieved 2015-06-06.

- "Whitespot" (PDF). UK: Fisheries Technical Services – Fish Health, Ageing and Species, Environment Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-11. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- Zaila, Kassandra E.; Cho, Deanna; Chang, Wei-Jan (2016). "18. Interactions between parasitic ciliates and their hosts: Ichthyophthirius multifiliis and Cryptocaryon irritans as examples". In Witzany, Guenther; Nowacki, Mariusz (eds.). Biocommunication of Ciliates. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. pp. 327–350. ISBN 9783319322094.

- Durborow, Robert; Mitchell, Andrew; Crosby, David (May 1998). "Ich (White Spot DIsease)". Southern Regional Aquaculture Center. 476.

- Green, Christopher; Haukenes, Alf (September 2015). "The Role of Stress in Fish Disease". Southern Regional Aquaculture Center. 474.

- Foster, Race; Smith, Marty. "Ich in Freshwater Fish: Causes, Treatment, and Prevention". PetCoach. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- https://aquaplantscare.uk/aquarium-white-spot-disease-ich-ichthyophthirius-multifiliis/

- Andrews, Chris; Carrington, Neville; Exell, Adrian (2010). Manual of fish health : everything you need to know about aquarium fish, their environment and disease prevention (2nd ed.). Richmond Hill, Ont.: Firefly Books. ISBN 9781554076918. OCLC 578105245.

- Peter Burgess (2016). "The essential guide to whitespot". Practical Fishkeeping. No. 7. pp. 60–63.

- Lin YK, Lin TL, Wang CC, Wang XT, Stieger K, Klopfleisch R, Clark TG (Mar 2002). "Variation in primary sequence and tandem repeat copy number among i-antigens of Ichthyophthirius multifiliis". Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 120 (1): 93–106. PMID 11849709.

- Xu, De-Hai (2014-02-01). "Preventing Ich". Tropical Fish Magazine. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ichthyophtiriosis. |