Human sperm competition

Sperm competition is a form of post-copulatory sexual selection[1] whereby male ejaculates simultaneously physically compete to fertilize a single ovum.[2] Sperm competition occurs between sperm from two or more rival males when they make an attempt to fertilize a female within a sufficiently short period of time.[3] This results primarily as a consequence of polyandrous mating systems, or due to extra-pair copulations of females, which increases the chance of cuckoldry, in which the male mate raises a child that is not genetically related to him.[1][3][4] Sperm competition among males has resulted in numerous physiological and psychological adaptations, including the relative size of testes, the size of the sperm midpiece, prudent sperm allocation, and behaviors relating to sexual coercion,[1][3][4][5] however this is not without consequences: the production of large amounts of sperm is costly[6][7] and therefore, researchers have predicted that males will produce larger amounts of semen when there is a perceived or known increase in sperm competition risk.[3][7] Sperm competition is not exclusive to humans, and has been studied extensively in other primates,[5][8][9] as well as throughout much of the animal kingdom.[10][11][12] The differing rates of sperm competition among other primates indicates that sperm competition is highest in primates with multi-male breeding systems, and lowest in primates with single-male breeding systems.[5][8] Compared to other animals, and primates in particular, humans show low-to-intermediate levels of sperm competition, suggesting that humans have a history of little selection pressure for sperm competition.[5]

Physiological adaptations to sperm competition

Physiological evidence, including testis size relative to body weight and the volume of sperm in ejaculations, suggests that humans have experienced a low-to-intermediate level of selection pressure for sperm competition in our evolutionary history.[4][5] Nevertheless, there is a large body of research that explores the physiological adaptations males do have for sperm competition.[3]

Testis size and body weight

Evidence suggests that, among the great apes, relative testis size is associated with the breeding system of each primate species.[13] In humans, testis size relative to body weight is intermediate between monogamous primates (such as gorillas) and promiscuous primates (such as chimpanzees), indicating an evolutionary history of moderate selection pressures for sperm competition.[4]

Ejaculate volume

The volume of sperm in ejaculates scales proportionately with testis size and, consistent with the intermediate weight of human males testis, ejaculate volume is also intermediate between primates with high and low levels of sperm competition.[4] Human males, like other animals, exhibit prudent sperm allocation, a physiological response to the high cost of sperm production as it relates to the actual or perceived risk of sperm competition at each insemination.[14] In situations where the risk of sperm competition is higher, males will allocate more energy to producing higher ejaculate volumes.[14] Studies have found that the volume of sperm does vary between ejaculates,[15] and that sperm produced during copulatory ejaculations are of a higher quality (younger, more motile, etc.) than those sperm produced during masturbatory ejaculates or nocturnal emissions.[3] This suggests that, at least within males, there is evidence of allocation of higher quality sperm production for copulatory purposes. Researchers have suggested that males produce more and higher quality sperm after spending time apart from their partners, implying that males are responding to an increased risk of sperm competition,[16] although this view has been challenged in recent years. It is also possible that males may be producing larger volumes of sperm in response to actions from their partners, or it may be that males who produce larger volumes of sperm may be more likely to spend more time away from their partners.[3]

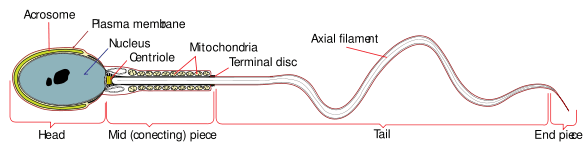

Size of sperm midpiece

The size of the sperm midpiece is determined in part by the volume of mitochondria in the sperm.[17] Sperm midpiece size is tied to sperm competition in that individuals with a larger midpiece will have more mitochondria, and will thus have more highly motile sperm than those with a lower volume of mitochondria.[17] Among humans, as with relative testis size and ejaculate volume, the size of the sperm midpiece is small compared to other primates, and is most similar in size to that of primates with low levels of sperm competition, supporting the theory that humans have had an evolutionary history of intermediate levels of sperm competition.[5]

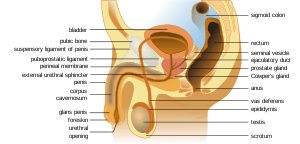

Penis anatomy

Several features of the anatomy of the human penis are proposed to serve as adaptations to sperm competition, including the length of the penis and the shape of the penile head. By weight, the relative penis size of human males is similar to that of chimpanzees, although the overall length of the human penis is the largest among primates.[18] It has been suggested by some authors that penis size is constrained by the size of the female reproductive tract (which, in turn is likely constrained by the availability of space in the female body), and that longer penises may have an advantage in depositing semen closer to the female cervix.[19] Other studies have suggested that over our evolutionary history, the penis would have been conspicuous without clothing, and may have evolved its increased size due to female preference for longer penises.[20]

The shape of the glans and coronal ridge of the penis may function to displace semen from rival males, although displacement of semen is only observed when the penis is inserted a minimum of 75% of its length into the vagina.[21] After allegations of female infidelity or separation from their partner, both men and women report that men thrusted the penis more deeply and more quickly into the vagina at the couple's next copulation.[21]

Psychological adaptations to sperm competition

In addition to physiological adaptations to sperm competition, men also have been shown to have psychological adaptations, including certain copulatory behaviors, behaviors relating to sexual coercion, investment in relationships, sexual arousal, performance of oral sex, and mate choice.

Copulatory behaviors

Human males have several physiological adaptations that have evolved in response to pressures from sperm competition, such as the size and shape of the penis.[21] In addition to the anatomy of male sex organs, men have several evolved copulatory behaviors that are proposed to displace rival male semen. For example, males who are at a higher risk of sperm competition (defined as having female partners with high reproductive value, such as being younger and physically attractive) engaged more frequently in semen-displacing behaviors during sexual intercourse than men who were at a lower risk of sperm competition.[22] These semen-displacing behaviors include deeper and quicker thrusts, increased duration of intercourse, and an increased number of thrusts.[21][22]

Sexual coercion and relationship investment

Men who are more invested into a relationship have more to lose if their female partner is engaging in extra-pair copulations.[3] This has led to the development of the cuckoldry risk hypothesis, which states that men who are at a higher risk of sperm competition due to female partner infidelity are more likely to sexually coerce their partners through threatening termination of the relationship, making their partners feel obligated to have sex, and other emotional manipulations of their partners, in addition to physically forcing partners to have sex.[23] In forensic cases, it has been found that men who rape their partners experienced cuckoldry risk prior to raping their partners.[24] Additionally, men who spend more time away from their partners are not only more likely to sexually coerce their partners, but they are also more likely to report that their partner is more attractive (as well as reporting that other men find her more attractive), in addition to reporting a greater interest in engaging in intercourse with her.[25] Men who perceive that their female partners spend time with other men also are more likely to report that she is more interested in copulating with him.[25]

Sexual arousal and sexual fantasies

Sperm competition has also been proposed to influence men’s sexual fantasies and arousal. Some researchers have found that much pornography contains scenarios with high sperm competition, and it is more common to find pornography depicting one woman with multiple men than it is to find pornography depicting one man with multiple women,[26] although this may be confounded by the fact that it is less expensive to hire male pornographic actors than female actors.[27] Kilgallon and Simmons documented that men produce a higher percentage of motile sperm in their ejaculates after viewing sexually explicit images of two men and one woman (a sperm competition risk) than after viewing sexually explicit images of three women, likely indicating a response to an active risk of sperm competition.[28]

Oral sex

It is unknown whether or not men’s willingness and desire to perform oral sex on their female partners is an adaptation.[3] Oral sex is not unique to humans,[29][30][31] and it is proposed to serve a number of purposes relating to sperm competition risk. Some researchers have proposed that oral sex may serve to assess the reproductive health of a female partner[32] and her fertility status,[33] to increase her arousal, thereby reducing the likelihood of her having extra-pair copulations,[34] to increase the arousal of the male to increase his semen quality, and thereby increase the likelihood of insemination,[35] or to detect the presence of semen of other males in the vagina.[32][36]

Mate choice

Sperm competition risk also influences males' choice of female partners. Men prefer to have as low of a sperm competition risk as possible, and they therefore tend to choose short-term sexual partners who are not in a sexual relationship with other men.[3] Women who are perceived as the most desirable short-term sexual partners are those who are not in a committed relationship and who also do not have casual sexual partners, while women who are in a committed long-term relationship are the least desirable partners.[37] Following the above, women who are at an intermediate risk of sperm competition, that is women who are not in a long-term relationship but who do engage in short-term mating or have casual sexual partners, are considered intermediate in desirability for short-term sexual partners.[37]

Effects of sperm competition on human mating strategies

High levels of sperm competition among the great apes are generally seen among species with polyandrous (multimale) mating systems, while lower rates of competition are seen in species with monogamous or polygynous (multifemale) mating systems.[4][5][38] Humans have low to intermediate levels of sperm competition, as seen by humans’ intermediate relative testis size, ejaculate volume, and sperm midpiece size, compared with other primates.[4][5] This suggests that there has been a relatively high degree of monogamous or polygynous behavior throughout our evolutionary history.[38] Additionally, the lack of a baculum in humans[39] suggests a history of monogamous mating systems.

Males have the goal of reducing sperm competition by selecting women who are at low risk for sperm competition as the most ideal mating partners.[37] On the other hand, women tend to seek to increase sperm competition risk by engaging in polyandrous extra-pair copulations, typically with males who are of a higher genetic quality than their usual partner, especially when women are in periods of high conception risk.[3][40]

Intra-ejaculate sperm competition

Even within ejaculates, sperm have adopted different morphologies. It has not been answered by the current scholarship if these different morphologies offer advantages in fertilization, but we can still model them as trade-offs (ATP expenditure vs. Longer tail) and as altruism (pairing) between sperm brothers. The next question ask is whether these differential strategies show any trends. If certain morphologies tend to become more common, it might mean that there is competition within sperm in the sense that not every sperm has the same chance of reaching the egg.

If each sperm contains a chromatid from one of the two kinds of pre-meiotic tetrad, then we have, loosely speaking, two kinds of sperm. This does not account for crossing-over, of course. A sperm has half a chance of having a homologous chromatid as any random sperm. The relatedness among sperm is ½, but not in the sense that it is between human brothers. A human brothers has on average 50% of his brother's genes. A sperm has (not accounting for crossing-over) either 0% or 100% of its brother's genes. Still, on the level of the gene, the relatedness between two sperm and two human brothers is practically the same. From the point of view of a gene in a sperm cell, there is a 50% chance that another given sperm will share that gene. Likewise, from the point of view of an autosomal gene in a human male, there is a 50% chance that his sibling will share that gene. Therefore, on the level of the gene, a sperm cell has just as much incentive to be altruistic toward its brother as a human brother has to be altruistic toward his brother.

Sperm differentiation within an ejaculate is restricted by their singularly particular mission and by there being a limited number of genes that express themselves post-meiotically. Nevertheless, they exhibit discretely differential morphologies within ejaculates (e.g. the apical hook, which facilitates what are called sperm trains as part of “exceptional sperm cooperation” (Moore et al. 2002 via Pitnick et al. p. 101))[41] and are the fastest evolving cells.

Female responses to sperm competition

Without non-monogamous mating of females, sperm competition would not exist in humans.[3] As human females invest more time and energy than males into reproduction through the processes of pregnancy and lactation, women prefer to mate with high quality males who have resources to invest in raising offspring.[40][42] Consequently, women have received benefits over the course of human evolutionary history by deliberately engaging in extra-pair copulations with other males during the time of ovulation.[3][40] Two possible benefits of this facultative polyandry are acquisition of resources from males to aid in raising offspring, as well as improving the genetic quality of their offspring by selecting to engage in extra-pair copulations with males with higher genetic quality than their usual partner.[3][43] Men have evolved increased vigilance of their female partners when she is at high-conception risk,[40] and as a result, to avoid sperm competition, some females will delay copulation with their partner following an extra-pair copulation during times of high conception risk.[3][44]

Women may also have a number of postcopulatory adaptations to sperm competition. The female orgasm has been suggested as such an adaptation.[3] Physiologically, some researchers have suggested that females may strategically time orgasms in order to selectively retain sperm from extra-pair partners,[45] and this research was supported by evidence that women tend to have a greater number of copulatory orgasms with males of higher genetic quality, measured by lower fluctuating asymmetry of the partners.[46] Psychologically, the female orgasm may be used as a mechanism to signal relationship satisfaction with a partner to reduce the likelihood of him having extra-pair copulations.[3] Indeed, women who suspect infidelity of their partners have been shown to report pretending orgasm more frequently than women who do not suspect infidelity.[47]

Sperm competition in other primates

The relative size of human male testes is comparable to those primates who have single-male (monogamous or polygynous) mating systems, such as gorillas and orangutans,[13] while it is smaller when compared to primates with polyandrous mating systems, such as bonobos and chimpanzees.[4][5][13] While it is possible that the large testis size of some primates could be due to seasonal breeding (and consequently a need to fertilize a large number of females in a short period of time), evidence suggests that primate groups with multi-male mating systems have significantly larger testes than do primates groups with single-male mating systems, regardless of whether that species exhibits seasonal breeding.[38] Similarly, primate species with high levels of sperm competition also have larger ejaculate volumes[4] and larger sperm midpieces.[5]

Unlike all other Old World great apes and monkeys, humans do not have a baculum (penile bone). Dixson[48] demonstrated that increased baculum length is associated with primates who live in dispersed groups, while small bacula are found in primates who live in pairs. Those primates that have multi-male mating systems tend to have bacula that are larger in size, in addition to prolongation of post-ejaculatory intromission and larger relative testis size.[21][49]

References

- Shackelford, Todd K.; Goetz, Aaron T. (2007). "Adaptation to sperm competition in humans". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 16 (1): 47–50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00473.x.

- Pham, Michael N.; Shackelford, Todd K. (2014). “Sperm competition and the evolution of human sexuality”. In T.K. Shackelford & R.D. Hansen. The Evolution of Sexuality. Cham: Springer. pp. 257-275. ISBN 9783319093840.

- Shackelford, Todd K.; Goetz, Aaron T.; LaMunyon, Craig W., Pham, Michael N; Pound, Nicholas. (2016). “Human sperm competition”. In D.M. Buss. The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley. pp. 427-443. ISBN 9781118755884.

- Simmons, Leigh W.; Firman, Renée C.; Rhodes, Gillian; Peters, Marianne. (2004). “Human sperm competition: Testis size, sperm production, and rates of extrapair copulations”. Animal Behaviour. 68 (2): 297-302.

- Martin, Robert D. (2007). “The evolution of human reproduction: A primatological perspective”. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology. 50: 59-84.

- Dewsbury, Donald A. (1982). “Ejaculate cost and male choice”. The American Naturalist. 119 (5): 601-610.

- Baker, R. Robin; Bellis, Mark A. (1993). “Human sperm competition: Ejaculate adjustment by males and the function of masturbation”. Animal Behaviour. 46 (5): 861-885.

- Møller, Anders Pape. (1988). “Ejaculate quality, testes size and sperm competition in primates”. Journal of Evolution. 17 (5): 479-488.

- Dixson, Alan F. (1987). “Observations on the evolution of the genitalia and copulatory behaviour in male primates”. Journal of Zoology. 213 (3): 423-443.

- Parker, G.A. (1970). “Sperm competition and its evolutionary consequences in the insects”. Biological Reviews. 55 (4): 525-567.

- Birkhead, T.R.; Møller, A.P. (1992). Sperm competition in birds: Evolutionary causes and consequences. London: Academic Press. ISBN 0121005402.

- Ginsberg, J.R.; Huck, U.W. (1989). “Sperm competition in mammals”. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 4 (3): 74-79.

- Harcourt, A.H.; Harvey, P.H.; Larson, S.G.; Short, R.V. (1981). “Testis weight, body weight and breeding system in primates”. Nature 293: 55-57.

- Wedell, Nina; Gage, Matthew J.G.; Parker, Geoffrey A. (2002). “Sperm competition, male prudence, and sperm-limited females”. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 17 (7): 313-320.

- Mallidis, C.; Howard, E.J.; Baker, H.W.G. (2008). “Variation of semen quality in normal men”. International Journal of Andrology. 14 (2): 99-107.

- Baker, R. Robin; Bellis, Mark A. (1989). “Number of sperm in human ejaculates varies in accordance with sperm competition theory”. Animal Behaviour. 37: 867-869.

- Anderson, Matthew J.; Dixson, Alan F. (2002). “Sperm competition: Motility and the midpiece in primates”. Nature. 416 (6880): 496.

- Short, R.V. (1979). “Sexual selection and its component parts, somatic and genital selection as illustrated by man and the great apes”. Advances in the Study of Behavior. 9: 131-158.

- Brown, Luther; Shumaker, Robert W.; Downhower, Jerry F. (1995). “Do primates experience sperm competition?” The American Naturalist. 146 (2): 302-306.

- Mautz, Brian S.; Wong, Bob B.M.; Peters, Richard A.; Jennions, Michael D. (2013). “Penis size interacts with body shape and height to influence male attractiveness”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States. 110 (17): 6925-6930.

- Gallup, Gordon G.; Burch, Rebecca L.; Zappieri, Mary L.; Parvez, Rizwan A.; Stockwell, Malinda L.; Davis, Jennifer A. (2003). “The human penis as a semen displacement device”. Evolution and Human Behavior. 24 (4): 277-289.

- Goetz, Aaron T.; Shackelford, Todd K.; Weekes-Shackelford, Viviana A.; Euler, Harald A.; Hoier, Sabine; Schmitt, David P.; LaMunyon, Craig W. (2005). “Mate retention, semen displacement, and human sperm competition: A preliminary investigation of tactics to prevent and correct female infidelity”. Personality and Individual Differences. 38 (4): 749-763.

- Goetz, Aaron T.; Shackelford, Todd K. (2009). “Sexual coercion in intimate relationships: A comparative analysis of the effects of women’s infidelity and men’s dominance and control”. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 38 (2): 226-234.

- Camilleri, Joseph A.; Quinsey, Vernon L. (2009). “Testing the cuckoldry risk hypothesis of partner sexual coercion in community and forensic samples”. Evolutionary Psychology. 7 (2): 164-178.

- Pham, Michael N.; Shackelford, Todd K. (2013). “The relationship between objective sperm competition risk and men’s copulatory interest is moderated by partner’s time spent with other men”. Human Nature. 24 (4): 476-485.

- Pound, Nicholas. (2002). “Male interest in visual cues of sperm competition risk”. Evolution and Human Behavior. 23 (6): 443-466.

- Escoffier, Jeffrey. (2007). “Porn star/stripper/escort: Economic and sexual dynamics in a sex work career”. Journal of Homosexuality. 53: 173-200.

- Kigallon, Sarah J.; Simmons, Leigh W. (2005). “Image content influences men’s semen quality”. Biology Letters. 1 (3): 253-255.

- Tan, Min; Jones, Gareth; Zhu, Guangjian; Ye, Jianping; Hong, Tiyu; Zhou, Shanyi; Zhang, Shuyi; Zhang, Libiao. (2009). “Fellatio by fruit bats prolongs copulation time”. PLOS One. 4 (10): e7595.

- Maruthupandian, Jayabalan; Marimuthi, Ganapathy. (2013). “Cunnilingus apparently increases duration of copulation in the Indian flying fox, Pteropus giganteus”. PLOS One. 8 (3): e59743.

- Sergiel, Agnieszka; Maślak, Robert; Zedrosser, Andreas; Paśko, Łukasz; Garshelis, David L.; Reljić, Slaven; Huber, Djuro. (2014). “Fellatio in captive brown bears: Evidence of long-term effects of suckling deprivation?”. Zoo Biology. 33 (4): 349-352.

- Baker, Robin. (1996). Sperm wars: Infidelity, sexual conflict, and other bedroom battles. London: Fourth Estate. ISBN 1857023560.

- Haselton, Martie G.; Gildersleeve, Kelly. (2011). “Can men detect ovulation?” Current Directions in Psychological Science. 20 (2): 87-92.

- Pham, Michael N.; Shackelford, Todd K. (2013). “Oral sex as mate retention behavior”. Personality and Individual Differences. 55 (2): 185-188.

- Pham, Michael N.; Shackelford, Todd K.; Welling, Lisa L.M.; Ehrke, Alyse D.; Sela, Yael; Goetz, Aaron T. (2013). “Oral sex, semen displacement, and sexual arousal: Testing the ejaculate adjustment hypothesis”. Evolutionary Psychology. 11 (5): 1130-1139.

- Pham, Michael N.; Shackelford, Todd K. (2013). “Oral sex as infidelity-detection”. Personality and Individual Differences. 54 (6): 792-795.

- Shackelford, Todd K.; Goetz, Aaron T.; LaMunyon, Craig W.; Quintus, Brian J.; Weekes-Shackelford, Viviana A. (2004). “Sex difference in sexual psychology produce sex similar preferences for a short term mate”. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 33 (4): 405-412.

- Harcourt, A.H.; Purvis, A.; Liles, L. (1995). “Sperm competition: Mating system, not breeding season, affects testes size of primates”. Functional Ecology. 9 (3): 468-476.

- Dixson, Alan F. (1987). “Baculum length and copulatory behavior in primates”. American Journal of Primatology. 13: 51-60.

- Gangestad, Steven W.; Thornhill, Randy; Garver, Christine E. (2002). “Changes in women’s sexual interests and their partners’ mate-retention tactics across the menstrual cycle: Evidence for shifting conflicts of interest”. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 269 (1494): 975-982.

- Moore, H. D., Dvorakova, K., Jenkins, N. & Breed, W. 2002. Exceptional sperm cooperation in the wood mouse. Nature, 418, 174-177.

- Buss, David M.; Barnes, Michael. (1986). “Preferences in human mate selection”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 50 (3): 559-570.

- Thornhill, Randy; Gangestad, Steve W. (1996). “The evolution of human sexuality”. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 11 (2): 98-102.

- Gallup, Gordon G.; Burch, Rebecca L; Berens Mitchell, Tracy J. (2006). “Semen displacement as a sperm competition strategy”. Human Nature. 17 (3): 253-264.

- Baker, R. Robin; Bellis, Mark A. (1993). “Human sperm competition: ejaculate manipulation by females and a function for the female orgasm”. Animal Behaviour. 46 (5): 887-909.

- Thornhill, Randy; Gangestad, Steve W.; Comer, Randall. (1995). “Human female orgasm and mate fluctuating asymmetry”. Animal Behaviour. 50 (6): 1601-1615.

- Kaighobadi, F.; Shackelford, T.K.; Weekes-Shackelford, V.A. (2012). “Do women pretend orgasm to retain a mate?” Archives of Sexual Behavior. 41 (5): 1121-1125.

- Dixson, Alan F. (1987). "Baculum length and copulatory behavior in primates". American Journal of Primatology. 13: 51–60. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350130107.

- Dixson, Alan F; Nyholt, Jenna; Anderson, Matt (2004). "A positive relationship between baculum length and prolonged intromission patterns in mammals". Current Zoology. 50 (4): 490–503.