History of intersex surgery

The history of intersex surgery is intertwined with the development of the specialities of pediatric surgery, pediatric urology, and pediatric endocrinology, with our increasingly refined understanding of sexual differentiation, with the development of political advocacy groups united by a human qualified analysis, and in the last decade by doubts as to efficacy, and controversy over when and even whether some procedures should be performed.

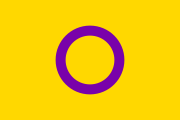

| Intersex topics |

|---|

|

|

Human rights and legal issues

|

|

Medicine and biology

|

|

Society and culture

|

|

History and events

|

|

Rights by country

|

|

See also

|

Prior to the medicalization of intersex, Canon and common law referred to a person's sex as male, female or hermaphrodite, with legal rights as male or female depending on the characteristics that appeared most dominant.[1] The foundation of common law, the Institutes of the Lawes of England described how a hermaphrodite could inherit "either as male or female, according to that kind of sexe which doth prevaile."[2][3] Single cases have been described by legal cases sporadically over the centuries. Modern ideas of medicalization of intersex and birth defects can be traced to French anatomist Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1805–1861), who pioneered the field of teratology.

Since the 1920s surgeons have attempted to "fix" an increasing variety of conditions. Success has often been partial and surgery is often associated with minor or major, transient or permanent complications. Techniques in all fields of surgery are frequently revised in a quest for higher success rates and lower complication rates. Some surgeons, well aware of the immediate limitations and risks of surgery, feel that significant rates of imperfect outcomes are no scandal (especially for the more severe and disabling conditions). Instead they see these negative outcomes as a challenge to be overcome by improving the techniques.[4] Genital reconstruction evolved within this tradition. In recent decades, nearly every aspect of this perspective has been called into question, with increasing concern regarding the human rights implications of medical interventions.

Surgical pioneering and constructed gender

Genital reconstructive surgery was pioneered between 1930 and 1960 by urologist Hugh Hampton Young and other surgeons at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore and other major university centers.[5] Understanding of intersex conditions was relatively primitive, based on identifying the type of gonad(s) by palpation or by surgery. Since ability to determine even the type of gonads in infancy was limited, sex of assignment and rearing were determined mainly by the appearance of the external genitalia. Most of Young's intersex patients were adults willingly seeking his help with physical problems of genital function.

Demand for surgery increased dramatically with better understanding of the condition congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) and availability of a new treatment (cortisone) by Lawson Wilkins, Frederick Bartter and others around 1950. For the first time, virilized infants with this variation were surviving and could be operated upon. A conflation was then established between life-saving treatment and cosmetic surgeries.[6] Hormone assays and karyotyping to ascertain sex chromosomes, and the availability of testosterone for treatment led to partial understanding of androgen insensitivity syndrome. Within a decade, most intersex cases could be accurately diagnosed and their future development predicted with some degree of confidence.

As the number of children with intersex conditions referred to Lawson Wilkins' new pediatric endocrinology clinic at Hopkins increased, it was recognized that doctors "couldn't tell by looking" at the external genitalia, and many errors of diagnosis based on outward appearance had led to anomalous sex assignments. Although it seems obvious now that a doctor could not announce to an eight-year-old boy and his parents that "we have just discovered that you are 'really' a girl, with female chromosomes, and ovaries and uterus inside, and we recommend that you change your sex to match your chromosomes and internal organs," a few such events occurred around the world as doctors and parents tried to make use of new information.

Genital reconstructive surgery at that time was primarily performed on older children and adults. In the early 1950s, it consisted primarily of the ability to remove an unwanted or nonfunctional gonad, to bring a testis into a scrotum, to repair a milder chordee or to change the position of the urethra in hypospadias, to widen a vaginal opening, and to remove a clitoris.

John Money, a pediatric clinical psychologist in the new "Psychohormonal Research Unit" at Hopkins and his partners, John and Joan Hampson, analyzed these assignments and reassignments in an attempt to learn the timing and sources of gender identity. In most of these patients, gender identity seemed to follow the sex of assignment and sex of rearing more closely than it did genes or hormones. This apparent primacy of social learning over biology became part of the intellectual underpinning of the feminist movement of the 1960s. In its application to children with intersex conditions, this thesis that sex was a many-faceted social construction changed the management of ambiguous genitalia from determination of the baby's real sex (by checking gonads or chromosomes) to determination of what sex should be assigned.

The most common intersex surgery offered in childhood was amputation of the clitoris and widening of the vaginal opening to make the genitals of a girl with CAH appear more conformed to the expectations. However, by the late 1950s surgical techniques for transforming an adult man into a woman were being developed in response to requests for such surgery from transsexuals.

Rise of infant surgery and "nurture over nature"

By the 1960s, the young specialties of pediatric surgery and pediatric urology at children's hospitals were universally admired for bringing infant birth defect surgery to new levels of success and safety. These specialized surgeons began to repair wider varieties of birth defects at younger ages with better results. Earlier correction reduced the social "differentness" of a child with a cleft lip, or club foot, or skull malformation, or could save the life of an infant with spina bifida.

Genital corrective surgeries in infancy were justified by (1) the belief that genital surgery is less emotionally traumatic if performed before the age of long-term memory, (2) the assumption that a firm gender identity would be best supported by genitalia that "looked the part," (3) the preference of parents for an "early fix," and (4) the observation of many surgeons that connective tissue, skin, and organs of infants heal faster, with less scarring than those of adolescents and adults. However, one of the drawbacks of surgery in infancy was that it would be decades before outcomes in terms of adult sexual function and gender identity could be assessed.

In North American and European societies, the 1960s saw the beginning of the "sexual revolution," characterized by increased public interest and discussion about sexuality, recognition of the value of sexuality in people's lives, the separation of sexuality from reproduction by increasing availability of contraception, the lessening of many social barriers and inhibitions related to sexual behavior, and social acknowledgment of women's sexuality. In this era, genes and hormones were thought not to have a strong influence on any aspect of human psychosexual development, gender identity, or sexual orientation.

The 1970s and 1980s were perhaps the decades when surgery and surgery-supported sex reassignment were most uncritically accepted in academic opinion, in most children's hospitals, and by society at large. In this context, enhancing the ability of people born with abnormalities of the genitalia to engage in "normal" heterosexual intercourse as adults assumed increasing importance as a goal of medical management. Many felt that a child could not become a happy adult if his penis was too small to insert in a vagina, or if her vagina was too small to receive a penis.[7][8]

By 1970, surgeons still considered it easier to "dig a hole" than "build a pole,"[9][10] but had abandoned "barbaric" clitorectomies in favor of "nerve sparing" clitoral recession and promised orgasms when the girls grew up. Pediatric endocrinology, surgery, child psychology, and sexuality textbooks recommended sex reassignment for a male whose penis was irreparably malformed or "too small to stand to urinate or penetrate a vagina," because the surgeons claimed to be able to construct vaginas where none existed.[11] The majority of these genetic males who were reassigned and surgically converted had cloacal exstrophy-type malformations or extreme micropenis (typically less than 1.5 cm). In 1972 John Money published his influential text[12] on the development of gender identity, and reported successful reassignment at age 22 months of a boy (David Reimer) who had lost his penis to a surgical accident. This experiment proved not to be as successful as Money claimed. David Reimer grew up as a girl, but never identified as one. Academic sexologist Milton Diamond later reported that Reimer failed to identify as female since the age of 9 to 11,[13] making the transition to living as a male at age 15. Reimer later went public with his story to discourage similar medical practices. He later committed suicide, owing to suffering years of severe depression, financial instability, and a troubled marriage.

Complications arise

Throughout the 1980s pediatric surgery textbooks recommended female assignment and feminizing reconstructive surgery for XY infants with a severely inadequate phallus. Nevertheless, in the 1980s several factors began to induce a decline in the frequency of certain types of genital surgery. Pediatric endocrinologists had realized that some boys with micropenis had deficiency of growth hormone which could be improved with hormones rather than surgery, and over the next decade a couple of reports suggested adult outcome as males was not as bad as expected for the boys with micropenis who had not had surgery. Although textbooks were slower to reflect the change, few reassignment surgeries for isolated micropenis were carried out by the 1990s.

In the 1980s research in both animals and humans began to provide evidence that sex hormones play an important role in early life in promoting or constraining adult sex-dimorphic sexual behavior and even gender identity. Examples of apparent androgen determination of gender identity in XY people with 5-alpha-reductase deficiency in the Dominican Republic had been published, along with reports of masculinized behavior in girls with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), and unsatisfactory sexual outcomes in adult women with CAH. Many endocrinologists were becoming skeptical that reassignment of genetic males to females was just a matter of learning and appearance, or that the newer clitoral reductions would be more successful than clitoral recessions.[14][15]

However, feminizing reconstructive surgery continued to be recommended and performed throughout the 1990s on most virilized infant girls with CAH, as well as infants with ambiguity due to androgen insensitivity syndrome, gonadal dysgenesis, and some XY infants with severe genital birth defects such as cloacal exstrophy.[16] Masculinizing reconstructive surgery continued on boys with severe hypospadias and the other conditions outlined above, with continued modifications and refinements intended to reduce unsatisfactory outcomes.[17][18]

Patient advocacy groups speak up

By 1990, biological factors were being reported for a wide variety of human behaviors and personality characteristics. The idea that culture accounted for all the differences between men and women seemed as obsolete as psychotherapy for homosexuality.

A more abrupt and sweeping re-evaluation of reconstructive genital surgery began about 1993, triggered by a combination of factors. One of the major factors was the rise of patient advocacy groups that expressed dissatisfaction with several aspects of their own past treatments. The Intersex Society of North America was the most influential and persistent, and advocated postponing genital surgery until a child is old enough to display a clear gender identity and consent to the surgery. Recommendations from these voices ranged from the unexceptionable (ending shame and secrecy, and providing more accurate information and counseling) to the radical (assigning a third sex or no sex at all to intersex infants). The idea that possession of abnormal genitalia in and of itself does not constitute a medical crisis was stressed. The claims of advocacy groups have been resisted. In response to a demonstration by members of the Intersex Society of North America outside the annual conference of the American Academy of Pediatrics in October 1996,[19][20] the Academy issued a press statement stating that:

- The Academy is deeply concerned about the emotional, cognitive, and body image development of intersexuals, and believes that successful early genital surgery minimizes these issues.

- Research on children with ambiguous genitalia has shown that a person’s sexual body image is largely a function of socialization, and children whose genetic sexes are not clearly reflected in external genitalia can be raised successfully as members of either sexes if the process begins before 2 1/2 years.

- Management and understanding of intersex conditions has significantly improved, particularly over the last several decades...[21]

In addition to ignoring patients' voices, physicians involved in intersex care had embarrassingly little long-term outcome data to support their claims. In 1997 a patient account was published which could not be ignored. David Reimer's tragic story, told in both popular and medical publications, was widely interpreted by the public and many physicians as a cautionary tale of medical hubris, of the folly of attempting to foil nature with nurture, of the importance of early hormones on brain development, and the risks and limitations of surgery.[22] Some clinicians proposed a moratorium on pediatric sex reassignment, particularly of undervirilized males as females, due to a lack of data that rearing or appearance of genitalia play a major part in gender identity development. Those clinicians encouraged delaying surgery until elected by adolescents in order to preserve sexual sensitivity.[23][24]

Similar controversy occurred in Europe and Latin America. In 1999 Colombia's constitutional court limited the ability of parents to consent to genital surgery for infants with intersex conditions. A number of advocacy groups argue against many forms of genital surgery in childhood.[25] In 2001, British surgeons argued for deferring vaginoplasty until adulthood on grounds of poor outcomes for women who were operated on as infants.[26]

Outcomes and evidence

A 2004 paper by Heino Meyer-Bahlburg and others examined outcomes from early surgeries in individuals with XY variations, at one patient centre.[27] The study has been used to support claims that "‘the majority of women...have clearly favored genital surgery at an earlier age" but the study was criticized by Baratz and Feder for neglecting to inform respondents that:

"(1) not having surgery at all might be an option; (2) they might have had lower rates of reoperation for stenosis if surgery were performed later, or (3) that significant technical improvements that were expected to improve outcomes had occurred in the 13 or 14 years between when they underwent early childhood surgery and when it might have been deferred until after puberty".[28]

In 2006, an invited group of clinicians met in Chicago and reviewed clinical evidence and protocols, argued that and adopted a new term for intersex conditions: "Disorders of sex development" (DSD). More specifically, these terms refer to "congenital conditions in which development of chromosomal, gonadal, or anatomical sex is atypical."[29] The term has been controversial and not widely adopted outside clinical settings: the World Health Organization and many medical journals still refer to intersex traits or conditions.[30] Academics like Georgiann Davis and Morgan Holmes, and clinical psychologists like Tiger Devore argue that the term DSD was designed to "reinstitutionalise" medical authority over intersex bodies.[31][32][33][34]

On surgical rationales and outcomes, the Consensus Statement on Intersex Disorders and their Management stated that:

It is generally felt that surgery that is carried out for cosmetic reasons in the first year of life relieves parental distress and improves attachment between the child and the parents. The systematic evidence for this belief is lacking. ... information across a range of assessments is insufficient ... outcomes from clitoroplasty identify problems related to decreased sexual sensitivity, loss of clitoral tissue, and cosmetic issues ... Feminising as opposed to masculinising genitoplasty requires less surgery to achieve an acceptable outcome and results in fewer urological difficulties... Long term data on sexual function and quality of life among those assigned female as well as male show great variability. There are no controlled clinical trials of the efficacy of early (less than 12 months of age) versus late surgery (in adolescence and adulthood), or of the efficacy of different techniques"[29]

Data presented in recent years suggests that little has changed in practice.[35] Creighton and others in the UK have found that there have been few audits of the implementation of the 2006 statement, clitoral surgeries on under-14s have increased since 2006, and "recent publications in the medical literature tend to focus on surgical techniques with no reports on patient experiences".[36] A 2014 civil society submission to the World Health Organization cited data from a large German Netzwerk DSD/Intersexualität study:

In a study in Lübeck conducted between 2005 and 2007 ... 81% of 439 individuals had been subjected to surgeries due to their intersex diagnoses. Almost 50% of participants reported psychological problems. Two thirds of the adult participants drew a connection between sexual problems and their history of surgical treatment. Participating children reported significant disturbances, especially within family life and physical well-being – these are areas that the medical and surgical treatment was supposed to stabilize.[37]

A 2016 Australian study of persons born with atypical sex characteristics found that "strong evidence suggesting a pattern of institutionalised shaming and coercive treatment of people". Large majorities of respondents opposed standard clinical protocols.[38]

A 2016 follow-up to the 2006 Consensus Statement, termed a Global Disorders of Sex Development Update stated,

There is still no consensual attitude regarding indications, timing, procedure and evaluation of outcome of DSD surgery. The levels of evidence of responses given by the experts are low (B and C), while most are supported by team expertise... Timing, choice of the individual and irreversibility of surgical procedures are sources of concerns. There is no evidence regarding the impact of surgically treated or non-treated DSDs during childhood for the individual, the parents, society or the risk of stigmatization... Physicians working with these families should be aware that the trend in recent years has been for legal and human rights bodies to increasingly emphasize preserving patient autonomy.[39]

A 2016 paper on "Surgery in disorders of sex development (DSD) with a gender issue" repeated many of the same claims, but without reference to human rights norms.[40] A commentary to that article by Alice Dreger and Ellen Feder criticized that omission, stating that issues have barely changed in two decades, with "lack of novel developments", while "lack of evidence appears not to have had much impact on physicians’ confidence in a standard of care that has remained largely unchanged."[41] Another 2016 commentary stated that the purpose of the 2006 Consensus Statement was to validate existing practices, "The authoritativeness and “consensus” in the Chicago statement lies not in comprehensive clinician input or meaningful community input, but in its utility to justify any and all forms of clinical intervention."[42]

Recent developments

Institutions like the Swiss National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics,[43] the Australian Senate,[32] the Council of Europe,[44][45] World Health Organization,[46][47] and UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights[48] and Special Rapporteur on Torture[49] have all published reports calling for changes to clinical practice and an end to harmful practices.

In 2011, Christiane Völling won the first successful case brought against a surgeon for non-consensual surgical intervention. The Regional Court of Cologne, Germany, awarded her €100,000.[50]

In April 2015, Malta became the first country to recognize a right to bodily integrity and physical autonomy, and outlaw non-consensual modifications to sex characteristics. The Act was widely welcomed by civil society organizations.[51][52][53][54][55]

In 2017, Human Rights Watch and Interact Advocates for Intersex Youth published a report documenting the negative effects of medically unnecessary surgeries on intersex children in the US, as well as the pressure placed on parents to consent to the operations without full information.[56] California State Legislature passed a resolution condemning the practice in 2018.[57]

The same year, Amnesty International published a report on the situation of intersex persons in Denmark and Germany[58] and launched a campaign for intersex human's rights: "First, Do No Harm: ensuring the rights of children born intersex".[59]

See also

- Intersex medical interventions

- Intersex in history

- Sex assignment

- Sex reassignment surgery

- (DoDI) 6130.03, 2018, section 5, 13f and 14m

Notes

- Raming, Ida; Macy, Gary; Bernard J, Cook (2004). A History of Women and Ordination. Scarecrow Press. p. 113.

- E Coke, The First Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England, Institutes 8.a. (1st Am. Ed. 1812) (16th European ed. 1812).

- Greenberg, Julie (1999). "Defining Male and Female: Intersexuality and the Collision Between Law and Biology". Arizona Law Review. 41: 277–278. SSRN 896307.

- Lobe, TE; Woodall DL; Richards GE; Cavallo A; Meyer WJ (1987). "The complications of surgery for intersex: changing patterns over two decades". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 22 (7): 651–2. doi:10.1016/S0022-3468(87)80119-7. PMID 3612461.

Improved techniques will lower the complication rate.

- Young, HH (1937). Genital Abnormalities, Hermaphroditism, and Related Adrenal Diseases. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins.

This was the standard work on intersex conditions until the middle of the 20th century, and helped establish the reputation of Johns Hopkins.

- Piaggio LA. Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: Review from a Surgeon's Perspective in the Beginning of the Twenty-First Century. Front Pediatr. 2014;1:50. Published 2014 Jan 2. doi:10.3389/fped.2013.00050

- Penny R. (1982). "Disorders of the testes". In: Kaplan S, ed. Clinical Pediatric and Adolescent Endocrinology.. Philadelphia: Saunders.

An example of a now-obsolete recommendation to consider reassigning a boy with severe micropenis as a girl.

- Oesterling JE, Gearhart JP, Jeffs RD (1987). "A unified approach to early reconstructive surgery of the child with ambiguous genitalia". J Urol. 138 (4 Pt 2): 1079–82. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(17)43508-7. PMID 3656565.

A report from Hopkins from the mid-1980s, describing varied approaches for variations of feminizing surgery, including a case of sex reassignment for micropenis.

- Hendrick, M. (1993). "Is it a Boy or a Girl?". Johns Hopkins Magazine: 10–16.

- Hester, J. David (2004). "Intersex(es) and informed consent: How physicians' rhetoric constrains choice". Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics. 25 (1): 21–49. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.693.6468. doi:10.1023/b:meta.0000025069.46031.0e. PMID 15180094.

- Walsh PC, Scott WW (1979). "Intersex". In: Ravitch MM, et al., eds. Pediatric surgery (3 ed.). . Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers.

Details of techniques for feminizing surgery from the first two decades, including an explanation of how the size of the phallus is the most important aspect of assignment decisions.

- Money J, Ehrhardt AA. Man & Woman, Boy & Girl. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1972.

- Diamond, Milton; Sigmundson, HK (March 1997). "Sex reassignment at birth. Long-term review and clinical implications". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 151 (3): 298–304. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170400084015. PMID 9080940. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- Passerini-Glazel G (1999). "Editorial: feminizing genitoplasty". J Urol. 161 (5): 1592–3. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(05)68987-2. PMID 10210422.

Restatement of the classic surgeon's arguments that (1) complications are being reduced by newer techniques, and (2) that surgery should optimally be performed even earlier (by 2 months of age) to take advantage of the estrogenized state of the tissue in early infancy.

- Thomas, D F M (2004). "Gender assignment: background and current controversies". BJU International. 93 (Supplement 3): 47–50. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.2004.04709.x. PMID 15086442.

- Rink RC, Adams MC (1998). "Feminizing genitoplasty: state of the art". World J Urol. 16 (3): 212–218. doi:10.1007/s003450050055. PMID 9666547.

Historical review of evolution of techniques for feminizing reconstruction.

- Migeon CJ, Wisniewski AB, Brown TR, Rock JA, Meyer-Bahlburg HF, Money J, Berkovitz GD (September 2002). "46,XY Intersex individuals: phenotypic and etiologic classification, knowledge of condition, and satisfaction with knowledge in adulthood". Pediatrics. 110 (3): electronic pages, pp. e32. doi:10.1542/peds.110.3.e32. PMID 12205282.

Between 1953 and the 1980s (i.e., all patients who were above 21 in 2000) 183 infants and children had been seen in the Hopkins pediatric endocrine clinic who had an XY karyotype and complete undervirilization, partial undervirilization (ambiguous genitalia), or micropenis. The 26 with complete undervirilization included 20 with complete androgen insensitivity and 6 with Swyer syndrome. All infants with complete undervirilization (i.e., female external genitalia) were raised as girls. Of the 43 with micropenis, 12 were reassigned as female and underwent feminizing surgery; 31 were raised as boys and treated with extra testosterone. Causes of partial undervirilization with ambiguity included defects of testosterone synthesis, partial gonadal dysgenesis, partial androgen insensitivity, Leydig cell hypoplasia, timing defects, true hermaphroditism, and multiple congenital anomalies. Of the 114 patients with ambiguity, 50 were raised as female (most with feminizing surgery) and 64 were raised as boys (some had surgery). They attempted to locate and survey all patients for outcome information. They located 73%, but 12% were developmentally delayed and 9% were deceased (2 from suicide). Of the 96 located, eligible adults, 78% consented to participate (18 women born with complete undervirilization, 18 women born with partial undervirilization, 21 men with partial virilization, 5 women born with micropenis, and 13 men born with micropenis). Roughly half of the patients had a satisfactory understanding of their condition; half wanted more.

- Wisniewski AB, Migeon CJ (2000). "Long-term perspectives for 46,XY patients affected by complete androgen insensitivity or congenital micropenis". Semin Reprod Med. 20 (3): 297–304. doi:10.1055/s-2002-35376. PMID 12428209.

Survey of patients treated with older management, including 5 with micropenis reassigned and raised as women. Gender identity was concordant with sex of assignment in all. Women with CAIS were satisfied with genitalia, men and women who had had micropenis were universally dissatisfied, but sexual function was better in men than women. Outcomes suggest infant reassignment to female and surgery does not produce an improved adult satisfaction with sexual function.

- Beck, Max. "Hermaphrodites with Attitude Take to the Streets". Hermaphrodites with Attitude.

- Holmes, Morgan (October 2015), "When Max Beck and Morgan Holmes went to Boston", Intersex Day

- American Academy of Pediatrics (October 1996). "American Academy of Pediatrics Position on Intersexuality". Intersex Day. Retrieved 2017-07-03.

- Colapinto, John (2000). As Nature Made Him: the Boy who was Raised as a Girl (the popular account of David Reimer's failed sex reassignment). New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-019211-2.

- Diamond, Milton (September 1999). "Pediatric management of ambiguous and traumatized genitalia". Journal of Urology. 162 (3 Pt 2): 1021–8. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)68054-6. PMID 10458424. Archived from the original on 2007-06-22.

- Reiner WG, Gearhart JP (2004). "Discordant sexual identity in some genetic males with cloacal exstrophy assigned to female sex at birth". N Engl J Med. 350 (4): 333–41. doi:10.1056/nejmoa022236. PMC 1421517. PMID 14736925.

Eight of 14 genetic males who were born with exstrophy and unsalvageable penis, assigned and raised as females, spontaneously reassigned themselves to male sex as they grew up. This outcome suggests XY infants with exstrophy but normal testes should not be raised as females.

- "The Rights of the Intersex Child". nocirc.org. National Organization of Circumcision Information Resource Centers (NOCIRC). 2007-02-13. Retrieved 2007-09-14.

- Creighton, Sarah; Minto, Catherine (2001-12-01). "Managing intersex: most vaginal surgery in childhood should be deferred". British Medical Journal. 323 (7324): 1264–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7324.1264. PMC 1121738. PMID 11731376.

- Meyer-Bahlburg, H.F.L.; Migeon, C.J.; Berkovitz, G.D.; Gearhart, J.P.; Dolezal, C.; Wisniewski, A.B. (2004). "Attitudes of Adult 46,XY Intersex Persons to Clinical Management Policies". The Journal of Urology. 171 (4): 1615–1619. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000117761.94734.b7. ISSN 0022-5347. PMID 15017234.

- Baratz, Arlene B.; Feder, Ellen K. (2015). "Misrepresentation of Evidence Favoring Early Normalizing Surgery for Atypical Sex Anatomies". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 44 (7): 1761–1763. doi:10.1007/s10508-015-0529-x. ISSN 0004-0002. PMC 4559568. PMID 25808721.

- Lee P. A.; Houk C. P.; Ahmed S. F.; Hughes I. A. (2006). "Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders". Pediatrics. 118 (2): e488–500. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0738. PMC 2082839. PMID 16882788.

- Rebecca Jordan-Young; Peter Sonksen; Katrina Karkazis (2014). "Sex, health, and athletes". BMJ. 348: g2926. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2926. PMID 24776640.

- An Interview with Dr. Tiger Howard Devore PhD, We Who Feel Differently, February 7, 2011.

- Australian Senate; Community Affairs References Committee (October 2013). Involuntary or coerced sterilisation of intersex people in Australia. Canberra: Community Affairs References Committee. ISBN 9781742299174.

- Georgiann Davis (2011), "DSD is a Perfectly Fine Term": Reasserting Medical Authority through a Shift in Intersex Terminology, in PJ McGann, David J. Hutson (ed.) Sociology of Diagnosis (Advances in Medical Sociology, Volume 12), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp.155-182

- Holmes, Morgan (2011). "The Intersex Enchiridion: Naming and Knowledge in the Clinic". Somatechnics. 1 (2): 87–114. doi:10.3366/soma.2011.0026.

- Dreger, Alice (April 3, 2015). "Malta Bans Surgery on Intersex Children". The Stranger SLOG.

- Creighton, Sarah M.; Michala, Lina; Mushtaq, Imran; Yaron, Michal (January 2, 2014). "Childhood surgery for ambiguous genitalia: glimpses of practice changes or more of the same?" (PDF). Psychology and Sexuality. 5 (1): 34–43. doi:10.1080/19419899.2013.831214. ISSN 1941-9899.

- Intersex Issues in the International Classification of Diseases: a revision (PDF). Mauro Cabral, Morgan Carpenter (eds.). 2014.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Jones, Tiffany; Hart, Bonnie; Carpenter, Morgan; Ansara, Gavi; Leonard, William; Lucke, Jayne (2016). Intersex: Stories and Statistics from Australia (PDF). Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers. ISBN 978-1-78374-208-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-09-14. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- Lee, Peter A.; Nordenström, Anna; Houk, Christopher P.; Ahmed, S. Faisal; Auchus, Richard; Baratz, Arlene; Baratz Dalke, Katharine; Liao, Lih-Mei; Lin-Su, Karen; Looijenga, Leendert H.J.; Mazur, Tom; Meyer-Bahlburg, Heino F.L.; Mouriquand, Pierre; Quigley, Charmian A.; Sandberg, David E.; Vilain, Eric; Witchel, Selma; and the Global DSD Update Consortium (2016-01-28). "Global Disorders of Sex Development Update since 2006: Perceptions, Approach and Care". Hormone Research in Paediatrics. 85 (3): 158–180. doi:10.1159/000442975. ISSN 1663-2818. PMID 26820577.

- Mouriquand, Pierre D. E.; Gorduza, Daniela Brindusa; Gay, Claire-Lise; Meyer-Bahlburg, Heino F. L.; Baker, Linda; Baskin, Laurence S.; Bouvattier, Claire; Braga, Luis H.; Caldamone, Anthony C.; Duranteau, Lise; El Ghoneimi, Alaa; Hensle, Terry W.; Hoebeke, Piet; Kaefer, Martin; Kalfa, Nicolas; Kolon, Thomas F.; Manzoni, Gianantonio; Mure, Pierre-Yves; Nordenskjöld, Agneta; Pippi Salle, J. L.; Poppas, Dix Phillip; Ransley, Philip G.; Rink, Richard C.; Rodrigo, Romao; Sann, Léon; Schober, Justine; Sibai, Hisham; Wisniewski, Amy; Wolffenbuttel, Katja P.; Lee, Peter (2016). "Surgery in disorders of sex development (DSD) with a gender issue: If (why), when, and how?". Journal of Pediatric Urology. 12 (3): 139–149. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.04.001. ISSN 1477-5131. PMID 27132944.

- Feder, Ellen K.; Dreger, Alice (May 2016). "Still ignoring human rights in intersex care". Journal of Pediatric Urology. 12 (6): 436–437. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.05.017. ISSN 1477-5131. PMID 27349148.

- Carpenter, Morgan (May 2016). "The human rights of intersex people: addressing harmful practices and rhetoric of change". Reproductive Health Matters. 24 (47): 74–84. doi:10.1016/j.rhm.2016.06.003. ISSN 0968-8080. PMID 27578341.

- Swiss National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics NEK-CNE (November 2012). On the management of differences of sex development. Ethical issues relating to "intersexuality".Opinion No. 20/2012 (PDF). 2012. Berne.

- Resolution 1952/2013, Provision version, Children’s right to physical integrity, Council of Europe, 1 October 2013

- Council of Europe; Commissioner for Human Rights (April 2015), Human rights and intersex people, Issue Paper

- World Health Organization (2015). Sexual health, human rights and the law. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 9789241564984.

- Eliminating forced, coercive and otherwise involuntary sterilization, An interagency statement, World Health Organization, May 2014.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (May 4, 2015), Discrimination and violence against individuals based on their sexual orientation and gender identity

- Report of the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, February 2013.

- Zwischengeschlecht (December 17, 2015). "Nuremberg Hermaphrodite Lawsuit: Michaela "Micha" Raab Wins Damages and Compensation for Intersex Genital Mutilations!" (text). Retrieved 2015-12-21.

- Cabral, Mauro (April 8, 2015). "Making depathologization a matter of law. A comment from GATE on the Maltese Act on Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics". Global Action for Trans Equality. Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- OII Europe (April 1, 2015). "OII-Europe applauds Malta's Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act. This is a landmark case for intersex rights within European law reform". Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- Carpenter, Morgan (April 2, 2015). "We celebrate Maltese protections for intersex people". Organisation Intersex International Australia. Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- Star Observer (2 April 2015). "Malta passes law outlawing forced surgical intervention on intersex minors". Star Observer.

- Reuters (1 April 2015). "Surgery and Sterilization Scrapped in Malta's Benchmark LGBTI Law". The New York Times.

- "US: Harmful Surgery on Intersex Children". Human Rights Watch. 2017-07-25. Retrieved 2019-03-01.

- "'A baby cannot provide ... consent': Calif. lawmakers denounce infant intersex surgeries". NBC News. Retrieved 2019-03-01.

- "Denmark and Germany: Authorities failing to protect intersex children from invasive surgery". www.amnesty.org. Retrieved 2019-08-23.

- "The rights of children born intersex". www.amnesty.org. Retrieved 2019-08-23.