Hematocrit

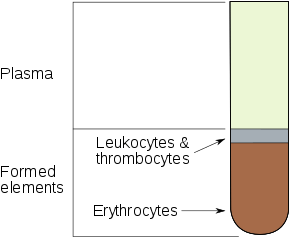

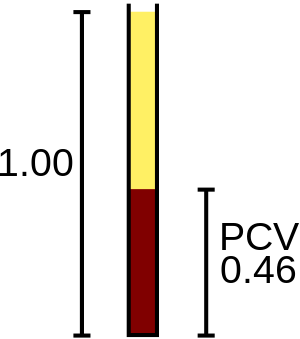

The hematocrit (/hɪˈmætəkrɪt/) (Ht or HCT), also known by several other names, is a blood test that measures the volume percentage (vol%) of red blood cells (RBC) in blood[1]. The measurement depends on the number and size of red bloods cells[2]. It is normally 40.7% to 50.3% for men and 36.1% to 44.3% for women.[3] It is a part of a person's complete blood count results[4], along with hemoglobin concentration, white blood cell count, and platelet count. Because the purpose of red blood cells is to transfer oxygen from the lungs to body tissues, a blood sample's hematocrit—the red blood cell volume percentage—can become a point of reference of its capability of delivering oxygen. Hematocrit levels that are too high or too low can indicate a blood disorder, dehydration, or other medical conditions[5]. An abnormally low hematocrit may suggest anemia, a decrease in the total amount of red blood cells, while an abnormally high hematocrit is called polycythemia.[6] Both are potentially life-threatening disorders.

| Hematocrit | |

|---|---|

| Medical diagnostics | |

Blood components | |

| MeSH | D006400 |

| MedlinePlus | 003646 |

Names

There are other names for the hematocrit, such as packed cell volume (PCV), volume of packed red cells (VPRC), or erythrocyte volume fraction (EVF). The term hematocrit (or haematocrit in British English) comes from the Ancient Greek words haima (αἷμα, "blood") and kritēs (κριτής, "judge"), and hematocrit means "to separate blood".[7][8] It was coined in 1891 by Swedish physiologist Magnus Blix as haematokrit,[9][10][11] modeled after lactokrit.

Measurement methods

With modern lab equipment, the hematocrit is calculated by an automated analyzer and is not directly measured. It is determined by multiplying the red cell count by the mean cell volume. The hematocrit is slightly more accurate as the PCV includes small amounts of blood plasma trapped between the red cells. An estimated hematocrit as a percentage may be derived by tripling the hemoglobin concentration in g/dL and dropping the units.[12]

The packed cell volume (PCV) can be determined by centrifuging heparinized blood in a capillary tube (also known as a microhematocrit tube) at 10,000 RPM for five minutes.[13] This separates the blood into layers. The volume of packed red blood cells divided by the total volume of the blood sample gives the PCV. Since a tube is used, this can be calculated by measuring the lengths of the layers.

Another way of measuring hematocrit levels is by optical methods such as spectrophotometry.[14] Through differential spectrophotometry, the differences in optical densities of a blood sample flowing through small-bore glass tubes at isosbestic wavelengths for deoxyhemoglobin and oxyhemoglobin and the product of the luminal diameter and hematocrit create a linear relationship that is used to measure hematocrit levels.[15]

There are some risks and side effects that accompany the tests of hematocrit because blood is being extracted from subjects. Subjects may experience a more than normal amount of hemorrhaging, hematoma, fainting, and possibly infection.[16]

While known hematocrit levels are used in detecting conditions, it may fail at times due to hematocrit being the measure of concentration of red blood cells through volume in a blood sample. It does not account for the mass of the red blood cells, and thus the changes in mass can alter a hematocrit level or go undetected while affecting a subject's condition.[17] Additionally, there have been cases in which the blood for testing was inadvertently drawn proximal to an intravenous line that was infusing packed red cells or fluids. In these situations, the hemoglobin level in the blood sample will not be the true level for the patient because the sample will contain a large amount of the infused material rather than what is diluted into the circulating whole blood. That is, if packed red cells are being supplied, the sample will contain a large amount of those cells and the hematocrit will be artificially very high.

Levels

Hematocrit can vary from the determining factors of the number of red blood cells. These factors can be from the age and sex of the subject.[18] Typically, a higher hematocrit level signifies the blood sample's ability to transport oxygen,[19] which has led to reports that an "optimal hematocrit level" may exist. Optimal hematocrit levels have been studied through combinations of assays on blood sample's hematocrit itself, viscosity, and hemoglobin level.[19]

Hematocrit levels also serve as an indicator of health conditions. Thus, tests on hematocrit levels are often carried out in the process of diagnosis of such conditions,[16] and may be conducted prior to surgery.[7] Additionally, the health conditions associated with certain hematocrit levels are the same as ones associated with certain hemoglobin levels.

As blood flows from the arterioles into the capillaries a change in pressure occurs. In order to maintain pressure, the capillaries branch off to a web of vessels that carry blood into the venules. Through this process blood undergoes micro-circulation. In micro-circulation, the Fåhræus effect will take place, resulting in a large change in hematocrit. As blood flows through the arterioles, red cells will act a feed hematocrit (Hf), while in the capillaries a tube hematocrit (Ht) occurs. In tube hematocrit plasma fills most of the vessel while the red cells travel through in somewhat of a single file line. From this stage, blood will enter the venules increasing in hematocrit, in other words the discharge hematocrit (Hd).

In large vessels with low hematocrit, viscosity dramatically drops and red cells take in a lot of energy. While in smaller vessels at the micro-circulation scale, viscosity is very high. With the increase in shear stress at the wall, a lot of energy is used to move cells.

Shear rate relations

Relationships between hematocrit, viscosity, and shear rate are important factors to put into consideration. Since blood is non-Newtonian, the viscosity of the blood is in relation to the hematocrit, and as a function of shear rate. This is important when it comes to determining shear force, since a lower hematocrit level indicates that there is a need for more force to push the red blood cells through the system. This is because shear rate is defined as the rate to which adjacent layers of fluid move in respect to each other.[20] Plasma is a more viscous material than typically red blood cells, since they are able to adjust their size to the radius of a tube; the shear rate is purely dependent on the amount of red blood cells being forced in a vessel.

Elevated

Generally at both sea levels and high altitudes, hematocrit levels rise as children mature.[21] These health-related causes and impacts of elevated hematocrit levels have been reported:

- Fall in blood plasma levels[6]

- Dehydration[16]

- Administering of Testosterone supplement therapy[22]

- In cases of dengue fever, a high hematocrit is a danger sign of an increased risk of dengue shock syndrome. Hemoconcentration can be detected by an escalation of over 20% in hematocrit levels that will come before shock. For early detection of dengue hemorrhagic fever, it is suggested that hematocrit levels be kept under observations at a minimum of every 24 hours; 3–4 hours is suggested in suspected dengue shock syndrome or critical cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever. [23]

- Polycythemia vera (PV), a myeloproliferative disorder in which the bone marrow produces excessive numbers of red cells, is associated with elevated hematocrit.

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and other pulmonary conditions associated with hypoxia may elicit an increased production of red blood cells. This increase is mediated by the increased levels of erythropoietin by the kidneys in response to hypoxia.

- Professional athletes' hematocrit levels are measured as part of tests for blood doping or erythropoietin (EPO) use; the level of hematocrit in a blood sample is compared with the long-term level for that athlete (to allow for individual variations in hematocrit level), and against an absolute permitted maximum (which is based on maximum expected levels within the population, and the hematocrit level that causes increased risk of blood clots resulting in strokes or heart attacks).

- Anabolic androgenic steroid (AAS) use can also increase the amount of RBCs and, therefore, impact the hematocrit, in particular the compounds boldenone and oxymetholone.

- Capillary leak syndrome also leads to abnormally high hematocrit counts, because of the episodic leakage of plasma out of the circulatory system.

- At higher altitudes, there is a lower oxygen supply in the air and thus hematocrit levels may increase over time.[24]

Hematocrit levels were also reported to be influenced by social factors that influence subjects. In the 1966–80 Health Examination Survey, there was a small rise in mean hematocrit levels in female and male adolescents that reflected a rise in annual family income. Additionally, a higher education in a parent has been put into account for a rise in mean hematocrit levels of the child.[25]

Lowered

Lowered hematocrit levels also pose health impacts. These causes and impacts have been reported:

- A low hematocrit level is a sign of a low red blood cell count. One way to increase the ability of oxygen transport in red blood cells is through blood transfusion, which is carried out typically when the red blood cell count is low. Prior to the blood transfusion, hematocrit levels are measured to help ensure the transfusion is necessary and safe.[26]

- A low hematocrit with a low mean corpuscular volume (MCV) with a high RDW suggests a chronic iron-deficient anemia resulting in abnormal hemoglobin synthesis during erythropoiesis.[27] The MCV and the red cell distribution width (RDW) can be quite helpful in evaluating a lower-than-normal hematocrit, because they can help the clinician determine whether blood loss is chronic or acute, although acute blood loss typically does not manifest as a change in hematocrit, since hematocrit is simply a measure of how much of the blood volume is made up of red blood cells. The MCV is the size of the red cells and the RDW is a relative measure of the variation in size of the red cell population.

- Decreased hematocrit levels could indicate life-threatening diseases such as leukemia.[28] When the bone marrow no longer produces normal red blood cells, hematocrit levels deviate from normal as well and thus can possibly be used in detecting acute myeloid leukemia.[29] It can also be related to other conditions, such as malnutrition, water intoxication, anemia, and bleeding.[16]

- Pregnancy may lead to women having additional fluid in blood. This could potentially lead to a small drop in hematocrit levels.[30]

References

- https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003646.htm

- "Hematocrit". MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- "Hematocrit". MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- "Hematocrit Test". MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- "Hematocrit Test". MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-02-15. Retrieved 2015-02-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Hematocrit - Health Encyclopedia - University of Rochester Medical Center". Archived from the original on 2015-02-14. Retrieved 2015-02-14.

- http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/hematocrit%5B%5D

- Blix, M.; Hedin, S. G. (1891). "Der Haematokrit" [The Haematokrit]. Zeitschrift für Analytische Chemie (in German). 30 (1): 652–54. doi:10.1007/BF01592182.

- Hedin, S. G. (1891). "Der Hämatokrit, ein neuer Apparat zur Untersuchung des Blutes" [The Haematokrit: a New Apparatus for the Investigation of Blood]. Skandinavisches Archiv für Physiologie (in German). 2 (1): 134–40. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.1891.tb00578.x.

- Medicine and the Reign of Technology, Stanley Joel Reiser, Cambridge University Press, February 27, 1981, p. 133

- "Hematocrit (HCT) or Packed Cell Volume (PCV)". Archived from the original on 2008-01-02.

- "Hematocrit". Encyclopedia of Surgery: A Guide for Patients and Caregivers. Archived from the original on 2006-06-12.

- "Method and apparatus for improving the accuracy of noninvasive hematocrit measurements". Archived from the original on 2015-02-14. Retrieved 2015-02-13.

- Lipowsky, Herbert H.; Usami, Shunichi; Chien, Shu; Pittman, Roland N. (1982). "Hematocrit determination in small bore tubes by differential spectrophotometry". Microvascular Research. 24 (1): 42–55. doi:10.1016/0026-2862(82)90041-3. PMID 7121311.

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Hematocrit

- Wintrobe's Clinical Hematology, Volume 1. Front Cover. John P. Greer. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009

- "Blood-Cell count – Jeremy E. Kaslow, M.D". Archived from the original on 2015-02-14. Retrieved 2015-02-13.

- Birchard, Geoffrey F. (1997). "Optimal Hematocrit: Theory, Regulation and Implications". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 37 (1): 65–72. doi:10.1093/icb/37.1.65. JSTOR 3883938.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-15. Retrieved 2015-04-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Góñez, Carmen; Donayre, Melita; Villena, Arturo; Gonzales, Gustavo F. (February 1993). "Hematocrit Levels in Children at Sea Level and at High Altitude: Effect of Adrenal Androgens". Human Biology. 65 (1): 49–57. JSTOR 41464361. PMID 8436390.

- Ohlander, SJ; Varghese, B; Pastuszak, AW. "Hematocrit elevation following testosterone therapy – does it increase risk of blood clots?". Nebido, Bayer AG. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- Dengue~workup at eMedicine

- Zubieta-Calleja, G. R.; Paulev, P. E.; Zubieta-Calleja, L; Zubieta-Castillo, G (2007). "Altitude adaptation through hematocrit changes" (PDF). Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 58 Suppl 5 (Pt 2): 811–18. PMID 18204195. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-02-15.

- Heald, Felix; Levy, Paul S.; Hamill, Peter V. V.; Rowland, Michael (1974). "Hematocrit values of youths 12–17 years" (PDF). Vital and Health Statistics. Series 11, Data from the National Health Survey (146): 1–40. PMID 4614557. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-11-13.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-02-14. Retrieved 2015-02-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Wallerstein, R. O. (April 1987). "Laboratory evaluation of anemia". The Western Journal of Medicine. 146 (4): 443–451. ISSN 0093-0415. PMC 1307333. PMID 3577135.

- http://udel.edu/~kschieff/leukemiadiagnosis.html#References Archived 2015-03-16 at the Wayback Machine

- http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/adultAML/Patient/page1#_3 Archived 2015-02-12 at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-02-14. Retrieved 2015-02-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)