Hemothorax

A hemothorax (derived from hemo- [blood] + thorax [chest], plural hemothoraces) is an accumulation of blood within the pleural cavity. The symptoms of a hemothorax include chest pain and difficulty breathing, while the clinical signs include reduced breath sounds on the affected side and a rapid heart rate. Hemothoraces are usually caused by an injury but may occur spontaneously: due to cancer invading the pleural cavity, as a result of a blood clotting disorder, as an unusual manifestation of endometriosis, in response to a collapsed lung, or rarely in association with other conditions.

| Hemothorax | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Haemothorax, haemorrhagic pleural effusion |

| |

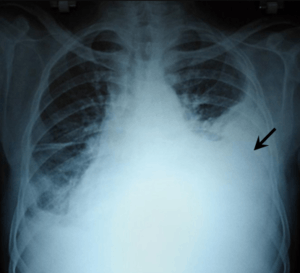

| Chest X-ray showing left sided hemothorax (arrowed) | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

| Symptoms | Chest pain, difficulty breathing |

| Complications | Empyema, Fibrothorax |

| Types | Traumatic, spontaneous |

| Causes | Trauma, rare conditions |

| Diagnostic method | X-ray, ultrasound, CT scan, MRI, thoracentesis |

| Treatment | Tube thoracostomy, thoracotomy fibrinolytic therapy |

| Medication | Streptokinase, urokinase |

| Prognosis | Favorable with treatment |

| Frequency | 300,000 cases in the US per year |

Hemothoraces are usually diagnosed using a chest X-ray, but can be identified using other forms of imaging including ultrasound, a CT scan, or an MRI scan. They can be differentiated from other forms of fluid within the pleural cavity by analysing a sample of the fluid, and are defined as having a hematocrit of greater than 50% that of the person's blood. Hemothoraces may be treated by draining the blood using a chest tube, but may require surgery if the bleeding continues. If treated, the prognosis is usually good. Complications of a hemothorax include infection within the pleural cavity and the formation of scar tissue.

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of a hemothorax depend on the quantity of blood that has been lost into the pleural cavity. A small hemothorax usually causes little in the way of symptoms, while larger hemothoraces commonly cause breathlessness and chest pain, and occasionally lightheadedness. Other symptoms may occur in association with a hemothorax depending on the underlying cause.[1]

The clinical signs of a hemothorax include reduced or absent breath sounds and reduced movement of the chest wall on the affected side.[1] When the affected side is tapped or percussed, a dull sound may be heard in contrast to the usual resonant note.[2] Large hemothoraces that interfere with the ability to transfer oxygen may cause a blue tinge to the lips (cyanosis). In these cases the body may try to compensate for the loss of blood, leading to a rapid heart rate (tachycardia), and pale, cool, clammy skin.[3]

Causes

Traumatic

A hemothorax is often caused by an injury, either blunt trauma or wounds that penetrate the chest, and these cases are referred to traumatic hemothoraces. Even relatively minor chest injuries can lead to significant hemothoraces. Injuries often cause the rupture of small blood vessels such as those found between the ribs. However, if larger blood vessels such as the aorta are damaged, the blood loss can be massive.[4][5]

Iatrogenic

Hemothorax can also occur as a complication of heart and lung surgery, for example the rupture of lung arteries caused by the placement of catheters.[6]

Non-traumatic

Less frequently, hemothoraces may occur spontaneously. A hemothorax can complicate some forms of cancer if the tumour invades the pleural space.[7] Tumours responsible for hemothoraces include angiosarcomas, schwannomas, mesothelioma, and lung cancer.[8] Hemothoraces are more likely to occur in response to very minor trauma when blood is less able to form clots, either as result of medications such as anticoagulants, or because of bleeding disorders such as haemophilia.[8] Rarely, hemothoraces can arise due to endometriosis, a condition in which tissue that normally covers the inside of the uterus forms in unusual locations.[9] Endometrial tissue that implants on the pleural surface can bleed in response to the hormonal changes of the menstrual cycle, causing what is known as a catamenial hemothorax as part of the thoracic endometriosis syndrome.[9] It represents 14% of cases of thoracic endometriosis syndrome.[10]

Those with an abnormal accumulation of air within the pleural space (a pneumothorax) can bleed into the cavity, which occurs in about 5% of cases of spontaneous pneumothorax.[8] The resulting combination of air and blood within the pleural space is known as a hemopneumothorax.

Rarely, hemothoraces can occur following spontaneous tearing of blood vessels such as in an aortic dissection, although bleeding in these circumstances is usually into the pericardial space.[8] Spontaneous tearing of blood vessels is more likely to occur in those with disorders that weaken blood vessels such as some forms of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, or in those with malformed blood vessels as is seen in Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome.[8] Other rare causes of hemothorax include neurofibromatosis type 1 and extramedullary haematopoiesis.[8]

Mechanisms

.jpg)

The thoracic cavity is a chamber within the chest, containing the lungs, heart, and numerous major blood vessels. Thin sheets of tissue known as the pleural membranes or pleura line the chest and cover the lungs - the chest wall is lined by the parietal pleura, while the visceral pleura covers the outside of the lungs. The visceral and parietal pleura are normally separated by only a thin layer of fluid, forming the pleural cavity.[11]

When a hemothorax occurs, blood enters the pleural cavity. The blood loss has several effects. Firstly, as blood builds up within the pleural cavity, it begins to interfere with the normal movement of the lungs, preventing one or both lungs from fully expanding and thereby interfering with the normal transfer of oxygen and carbon dioxide to and from the blood.[12] Secondly, blood that has been lost into the pleural cavity can no longer be circulated. Hemothoraces can lead to very significant blood loss - each half of the thorax can hold more than 1500 milliliters of blood, representing more than 25% of an average adult's total blood volume.[13] The body may struggle to cope with this blood loss, and in order to compensate tries to maintain blood pressure by forcing the heart to pump harder and faster, and by squeezing or constricting small blood vessels in the arms and legs.[14] These compensatory mechanisms can be recognised by a rapid resting heart rate and cool fingers and toes.[15]

If the blood within the pleural cavity is not removed, it will eventually clot. This clot tends to stick the parietal and visceral pleura together and has the potential to lead to scarring within the pleura, which if extensive leads to the condition known as a fibrothorax.[6] Following the initial loss of blood, a small hemothorax may irritate the pleura, causing additional fluid to seep out, leading to a bloodstained pleural effusion.[16] Furthermore, as enzymes in the pleural fluid begin to break down the clot, the protein concentration of the pleural fluid increases. As a result, the osmotic pressure of the pleural cavity increases, causing fluid to leak into the pleural cavity from the surrounding tissues.[17]

Diagnosis

Hemothoraces are most commonly detected using a chest X-ray, although ultrasound is sometimes used in an emergency setting. However, plain X-rays may miss smaller hemothoraces while other imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging may be more sensitive.[18] In cases where the nature of an effusion is in doubt, a sample of fluid can be aspirated and analysed in a procedure called thoracentesis.[8]

Chest X-ray

A chest X-ray is the most common technique used to diagnosis a hemothorax.[19] X-rays should ideally be taken in an upright position (an erect chest X-ray), but may be performed with the person lying on their back (supine) if an erect chest X-ray is not feasible. On an erect chest X-ray, a hemothorax is suggested by blunting of the costophrenic angle or partial or complete opacification of the affected half of the thorax. On a supine film the blood tends to layer in the pleural space, but can be appreciated as a haziness of one half of the thorax relative to the other.

A small hemothorax may be missed on a chest X-ray as several hundred milliliters of blood can be hidden by the diaphragm and abdominal viscera on an erect film. Supine X-rays are even less sensitive and as much as one liter of blood can be missed on a supine film.[20]

Other forms of imaging

.png)

Ultrasonography may also be used to detect hemothorax and other pleural effusions. This technique is of particular use in the critical care and trauma settings as it provides rapid, reliable results at the bedside.[19] Ultrasound is more sensitive than chest x-ray in detecting hemothorax.[21]

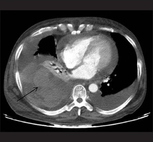

Computed tomography (CT or CAT) scans may be useful for diagnosing retained hemothorax as this form of imaging can detect much smaller amounts of fluid than a plain chest X-ray. However, CT is less used as a primary means of diagnosis within the trauma setting, as these scans require a critically ill person to be transported to a scanner, are slower, and require the subject to remain supine.[19][22]

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to differentiate between a hemothorax and other forms of pleural effusion, and can suggest how long the hemothorax has been present for. Fresh blood can be seen as a fluid with low T1 but high T2 signals, while blood that has been present for more than a few hours displays both low T1 and T2 signals.[23] MRI is used infrequently in the trauma setting due to the prolonged time required to perform an MRI, and the deterioration in image quality that occurs with motion.[18]

Thoracentesis

Although imaging techniques can demonstrate that fluid is present within the pleural space, it may be unclear what this fluid represents. To establish the nature of the fluid, a sample can be removed by inserting a needle into the pleural cavity in a procedure known as a thoracentesis or pleural tap. In this context, the most important assessment of the pleural fluid is the percentage by volume that is taken up by red blood cells (the hematocrit), which can be estimated by dividing the red blood cell count of the pleural fluid by 100,000.[7] A hemothorax is defined as having a hematocrit of at least 50% of that found in the affected person's blood, although the hematocrit of a chronic hemothorax may be between 25 and 50% if additional fluid has been secreted by the pleura.[8] Thoracentesis is the test most commonly used to diagnose a hemothorax in animals.[24]

Management

The management of a hemothorax depends largely on the extent of bleeding. While small haemothoraces may require little in the way of treatment, larger hemothoraces may require fluid resuscitation to replace the blood that has been lost, drainage of the blood within the pleural space using a procedure known as a tube thoracostomy, and potentially surgery in the form of a thoracotomy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) to prevent further bleeding.[7][19][12][8][25] Additional treatment options include antibiotics to reduce the risk of infection and fibrinolytic therapy to break down clotted blood within the pleural space.[7]

Thoracostomy

Blood in the cavity can be removed by inserting a drain (chest tube) in a procedure called a tube thoracostomy. This procedure is indicated for most causes of haemothorax, but should be avoided in aortic rupture which should be managed with immediate surgery.[4] The thoracostomy tube is usually placed between the ribs in the sixth or seventh intercostal space at the mid-axillary line.[12] It is important to avoid a chest tube becoming obstructed by clotted blood as obstruction prevents adequate drainage of the pleural space. Clotting occurs as the clotting cascade is activated when the blood leaves the blood vessels and comes into contact with the pleural surface, injured lung or chest wall, or the thoracostomy tube. Inadequate drainage may lead to a retained hemothorax, increasing the risk of infection within the pleural space (empyema) or the formation of scar tissue (fibrothorax).[26] Thoracostomy tubes with a diameter of 24–36 F (large-bore tubes) should be used, as these reduce the risk of blood clots obstructing the tube. Manual manipulation of chest tubes (also referred to as milking, stripping, or tapping) is commonly performed to maintain an open tube, but no conclusive evidence has demonstrated that this improves drainage.[8][27] If a chest tube does become obstructed, the tube can be cleared using open or closed techniques.[28] Tubes should be removed as soon as drainage has stopped, as prolonged tube placement increases the risk of empyema.[29][30]

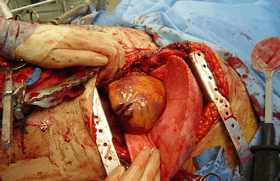

Surgery

10–20% of traumatic hemothoraces require surgical management.[30] Larger hemothoraces, or those that continue to bleed following drainage may require surgery. This surgery may take the form of a traditional open-chest procedure (a thoracotomy), but may be performed using video-associated thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). While there is no universally accepted cutoff for the volume of blood loss required before surgery is indicated, generally accepted indications include more than 1500 mL of blood drained from a thoracostomy, more than 200 mL of blood drained per hour, hemodynamic instability, or the need for repeat blood transfusions.[8][30][31] VATS is less invasive and cheaper than an open thoracotomy, and can reduce the length of hospital stay, but a thoracotomy may be preferred when hypovolaemic shock is present.[32][33] The procedure should ideally be performed within 72 hours of the injury as delay may increase the risk of complications.[6] In clotted hemothorax, VATS is the gold standard procedure to remove the clot, and is indicated if the hemothorax fills 1/3 or more of a hemithorax. The ideal time to remove a clot using VATS is at 48–96 hours, but can be attempted up to nine days after the injury.[30]

Other

Resuscitation with intravenous fluids or with blood products may be required. In fulminant cases, transfusions may be administered before admission to the hospital. Clotting abnormalities, such as those caused by anticoagulant medications, should be reversed.[34] Prophylactic antibiotics should be given for 24 hours in the case of trauma.

Blood clots may be retained within the pleural cavity despite chest tube drainage. Such retained clots should be removed, preferably with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). If VATS is unavailable, an alternative is fibrinolytic therapy such as streptokinase or urokinase given directly into the pleural space seven to ten days after the injury.[30] Residual clot that does not dissipate in response to fibrinolytics may require surgical removal in the form of decortication.[6]

Prognosis

The prognosis following a hemothorax depends on its size, the treatment given, and the underlying cause. While small hemothoraces may cause little in the way of problems, in severe cases an untreated hemothorax may be rapidly fatal due to uncontrolled blood loss. If left untreated, the accumulation of blood may put pressure on the mediastinum and the trachea, limiting the heart's ability to fill. However, if treated, the prognosis following a traumatic hemothorax is usually favourable and dependent on other injuries that have been sustained at the same time. Hemothoraces caused by benign conditions such as endometriosis have a good prognosis, while those caused by neurofibromatosis type 1 has a 36% rate of death, and those caused by aortic rupture are often fatal.[8][4]

Complications

Complications can occur following a hemothorax, and are more likely to occur if the blood has not been adequately drained from the pleural cavity.[33][32] Blood that remains within the pleural space can become infected, and is known as an empyema. The retained blood can also irritate the pleura, causing scar tissue to form. If extensive, this scar tissue can encase the lung, restricting movement of the chest wall, and is then referred to as a fibrothorax.[6] Other potential complications include atelectasis, lung infection, intrathoracic hematoma, wound infection, pneumothorax, or sepsis.[35]

Epidemology

There are about 300,000 cases of hemothorax in the U.S every year.[6] Polytrauma (injury to multiple body systems) involves chest injuries in 60% of cases and commonly leads to hemothorax.[6] About 37% of people hospitalized for blunt chest trauma have traumatic hemothorax.[30]

See also

Additional images

Chest X-ray showing a massive right hemothorax

Chest X-ray showing a massive right hemothorax- CT scan of the chest showing a hemothorax with severe lung contusions.

CT scan of the chest showing a hemothorax caused by warfarin use

CT scan of the chest showing a hemothorax caused by warfarin use CT scan of the chest showing a hemothorax caused by warfarin use.

CT scan of the chest showing a hemothorax caused by warfarin use.

References

- "Hemothorax: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2019-02-02.

- "Penetrating Chest Trauma". EMS World. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- "Hemothorax". Merck Manuals Consumer Version. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- Seligson, Marc T.; Marx, William H. (2019), "Aortic Rupture", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29083613, retrieved 2019-03-10

- "Aortic rupture, chest x-ray: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia Image". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- Boersma WG, Stigt JA, Smit HJ (2010). "Treatment of haemothorax". Respir Med. 104 (11): 1583–1587. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2010.08.006. PMID 20817498.

- Light, Richard W. (2007). Pleural Diseases. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 340, 341, 342. ISBN 9780781769570.

- Patrini D, Panagiotopoulos N, Pararajasingham J, Gvinianidze L, Iqbal Y, Lawrence DR (2015). "Etiology and management of spontaneous haemothorax". J Thorac Dis. 7 (3): 520–526. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.12.50. PMC 4387396. PMID 25922734.

- Rousset, P.; Rousset-Jablonski, C.; Alifano, M.; Mansuet-Lupo, A.; Buy, J.-N.; Revel, M.-P. (2014). "Thoracic endometriosis syndrome: CT and MRI features". Clinical Radiology. 69 (3): 323–330. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2013.10.014. ISSN 0009-9260. PMID 24331768.

- Regnard, Jean François; Cancellieri, Alessandra; Trisolini, Rocco; Alifano, Marco (2006-02-01). "Thoracic Endometriosis: Current Knowledge". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 81 (2): 761–769. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.07.044. ISSN 0003-4975. PMID 16427904.

- Snell, Richard S. (1995). Clinical anatomy for medical students (5th ed.). Boston: Little, Brown. pp. 77–81. ISBN 0316801356. OCLC 31410594.

- Broderick, SR (2013). "Hemothorax". Thoracic Surgery Clinics. 23 (1): 89–96. doi:10.1016/j.thorsurg.2012.10.003. ISSN 1547-4127. PMID 23206720.

- American College of Surgeons (2018). Advanced Trauma Life Support - student course manual (10th ed.). p. 68. ISBN 978-0-9968262-3-5.

- Institute of Medicine Staff; David E Longnecker; Andrew MacPherson Pope; Geoffrey French (1999). Fluid Resuscitation: State of the Science for Treating Combat Casualties and Civilian Injuries. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. ISBN 0309064813. OCLC 994446545.

- Hooper, Nicholas; Armstrong, Tyler J. (2019), "Shock, Hemorrhagic", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29262047, retrieved 2019-04-08

- Light RW (2010). "Pleural effusion in pulmonary embolism". Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 31 (6): 716–22. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1269832. PMID 21213203.

- Jones, David; Nelson, Anna; Ma, O. John (2016), Tintinalli, Judith E.; Stapczynski, J. Stephan; Ma, O. John; Yealy, Donald M. (eds.), "Pulmonary Trauma", Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (8th ed.), McGraw-Hill Education, retrieved 2019-02-08

- Hallifax RJ, Talwar A, Wrightson JM, Edey A, Gleeson FV (2017). "State-of-the-art: Radiological investigation of pleural disease". Respiratory Medicine. 124: 88–99. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2017.02.013. ISSN 1532-3064. PMID 28233652.

- Weldon E, Williams J (2012). "Pleural disease in the emergency department". Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 30 (2): 475–499, ix–x. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2011.10.012. PMID 22487115.

- "Hemothorax Workup: Approach Considerations, Laboratory Studies, Chest Radiography". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved 2019-02-16.

- Gomez, LP; Tran, VH (March 2019). Hemothorax. PMID 30855807.

- Cannon K, Checchi K, Wisniewski P (2016). "Retained Hemothorax" (PDF). Surgical Critical Care Evidence-Based Medicine Guidelines Committee.

- Kao S, Yen A, Nakanote K, Brouha S (2016). "Silver lining: Imaging manifestations of pleural pathology". Applied Radiology. 45 (6): 9–23.

- Slensky K (2009). "Chapter 153: Thoracic Trauma". In Silverstein DC, Hopper K (eds.). Small Animal Critical Care Medicine. pp. 662–667. doi:10.1016/B978-1-4160-2591-7.10153-5. ISBN 978-1-4160-2591-7.

- "Hemothorax". fpnotebook.com. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- Kwiatt, M; Tarbox, A; Seamon, MJ; Swaroop, M; Cipolla, J; Allen, C; Hallenbeck, S; Davido, HT; Lindsey, DE (2014). "Thoracostomy tubes: A comprehensive review of complications and related topics". International Journal of Critical Illness and Injury Science. 4 (2): 143–155. doi:10.4103/2229-5151.134182. ISSN 2229-5151. PMC 4093965. PMID 25024942.

- Salmon, Nadine; Lynch, Shelley; Muck, Kelly (2007-08-30). "Chest tube management" (PDF).

- Miller KS, Sahn SA (1987). "Chest tubes. Indications, technique, management and complications". Chest. 91 (2): 258–264. doi:10.1378/chest.91.2.258. PMID 3542404.

- Filosso, Pier Luigi; Sandri, Alberto; Guerrera, Francesco; Ferraris, Andrea; Marchisio, Filippo; Bora, Giulia; Costardi, Lorena; Solidoro, Paolo; Ruffini, Enrico (July 2016). "When size matters: changing opinion in the management of pleural space—the rise of small-bore pleural catheters". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 8 (7): E503–E510. doi:10.21037/jtd.2016.06.25. ISSN 2072-1439. PMC 4958830. PMID 27499983.

- Light, RW (2013). "Chapter 25: Hemothorax". Pleural Diseases (6th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 405–411. ISBN 978-1-4511-7599-8.

- "Hemothorax". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 2019-02-07.

- Chou YP, Lin HL, Wu TC (2015). "Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for retained hemothorax in blunt chest trauma". Curr Opin Pulm Med. 21 (4): 393–398. doi:10.1097/mcp.0000000000000173. PMC 5633323. PMID 25978625.

- Huggins JT, Sahn SA (2004). "Causes and management of pleural fibrosis". Respirology. 9 (4): 441–7. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1843.2004.00630.x. PMID 15612954.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK) (2016). Major Trauma: Assessment and Initial Management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Clinical Guidelines. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK). PMID 26913320.

- "Hemothorax: Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment - Symptoma®". www.symptoma.com. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |