Influenza A virus subtype H1N1

Influenza (H1N1) virus is the subtype of influenza A virus that was the most common cause of human influenza (flu) in 2009, and is associated with the 1918 outbreak known as the Spanish flu.

| Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 | |

|---|---|

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Insthoviricetes |

| Order: | Articulavirales |

| Family: | Orthomyxoviridae |

| Genus: | Alphainfluenzavirus |

| Species: | Influenza A virus |

| Serotype: | Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 |

| Strains | |

| |

| Influenza (Flu) |

|---|

|

| Types |

|

| Vaccines |

|

| Treatment |

| Pandemics |

|

| Outbreaks |

|

| See also |

|

It is an orthomyxovirus that contains the glycoproteins haemagglutinin and neuraminidase. For this reason, they are described as H1N1, H1N2 etc. depending on the type of H or N antigens they express with metabolic synergy. Haemagglutinin causes red blood cells to clump together and binds the virus to the infected cell. Neuraminidase is a type of glycoside hydrolase enzyme which helps to move the virus particles through the infected cell and assist in budding from the host cells.[1]

Some strains of H1N1 are endemic in humans and cause a small fraction of all influenza-like illness and a small fraction of all seasonal influenza. H1N1 strains caused a small percentage of all human flu infections in 2004–2005.[2] Other strains of H1N1 are endemic in pigs (swine influenza) and in birds (avian influenza).

In June 2009, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the new strain of swine-origin H1N1 as a pandemic. This strain is often called swine flu by the public media. This novel virus spread worldwide and had caused about 17,000 deaths by the start of 2010. On August 10, 2010, the World Health Organization declared the H1N1 influenza pandemic over, saying worldwide flu activity had returned to typical seasonal patterns.[3]

Swine influenza

Swine influenza (swine flu or pig flu) is a respiratory disease that occurs in pigs that is caused by the Influenza A virus. Influenza viruses that are normally found in swine are known as swine influenza viruses (SIVs). The known SIV strains include influenza C and the subtypes of influenza A known as H1N1, H1N2, H3N1, H3N2 and H2N3. Pigs can also become infected with the H4N6 and H9N2 subtypes.[4]

Swine influenza virus is common throughout pig populations worldwide. Transmission of the virus from pigs to humans is not common and does not always lead to human influenza, often resulting only in the production of antibodies in the blood. If transmission does cause human influenza, it is called zoonotic swine flu or a variant virus. People with regular exposure to pigs are at increased risk of swine flu infection. The meat of an infected animal poses no risk of infection when properly cooked.

Pigs experimentally infected with the strain of swine flu that caused the human pandemic of 2009–10 showed clinical signs of flu within four days, and the virus spread to other uninfected pigs housed with the infected ones.[5]

During the mid-20th century, identification of influenza subtypes became possible, allowing accurate diagnosis of transmission to humans. Since then, only 50 such transmissions have been confirmed. These strains of swine flu rarely pass from human to human. Symptoms of zoonotic swine flu in humans are similar to those of influenza and of influenza-like illness in general, namely chills, fever, sore throat, muscle pains, severe headache, coughing, weakness, and general discomfort. The recommended time of isolation is about five days.

Notable incidents

Spanish flu

The Spanish flu, also known as la grippe, La Gripe Española, or La Pesadilla, was an unusually severe and deadly strain of avian influenza, a viral infectious disease, that killed some 50 to 100 million people worldwide over about a year in 1918 and 1919. It is thought to be one of the deadliest pandemics in human history.

The 1918 flu caused an unusual number of deaths, possibly due to it causing a cytokine storm in the body.[6][7] (The current H5N1 bird flu, also an Influenza A virus, has a similar effect.)[8] The Spanish flu virus infected lung cells, leading to overstimulation of the immune system via release of cytokines into the lung tissue. This leads to extensive leukocyte migration towards the lungs, causing destruction of lung tissue and secretion of liquid into the organ. This makes it difficult for the patient to breathe. In contrast to other pandemics, which mostly kill the old and the very young, the 1918 pandemic killed unusual numbers of young adults, which may have been due to their healthy immune systems mounting a too-strong and damaging response to the infection.[9]

The term "Spanish" flu was coined because Spain was at the time the only European country where the press were printing reports of the outbreak, which had killed thousands in the armies fighting World War I (1914-1918). Other countries suppressed the news in order to protect morale.[10]

Fort Dix outbreak

In 1976, a novel swine influenza A (H1N1) caused severe respiratory illness in 13 soldiers, with one death at Fort Dix, New Jersey. The virus was detected only from January 19 to February 9 and did not spread beyond Fort Dix.[11] Retrospective serologic testing subsequently demonstrated that up to 230 soldiers had been infected with the novel virus, which was an H1N1 strain. The cause of the outbreak is still unknown and no exposure to pigs was identified.[12]

Russian flu

The 1977–1978 Russian flu epidemic was caused by strain Influenza A/USSR/90/77 (H1N1). It infected mostly children and young adults under 23; because a similar strain was prevalent in 1947–57, most adults had substantial immunity. Because of a striking similarity in the viral RNA of both strains – one which is unlikely to appear in nature due to antigenic drift – it was speculated that the later outbreak was due to a laboratory incident in Russia or Northern China, though this was denied by scientists in those countries.[13][14][15] The virus was included in the 1978–1979 influenza vaccine.[16][17][18][19]

- See also 1889–1890 flu pandemic for the earlier Russian flu pandemic caused either by H3N8 or H2N2

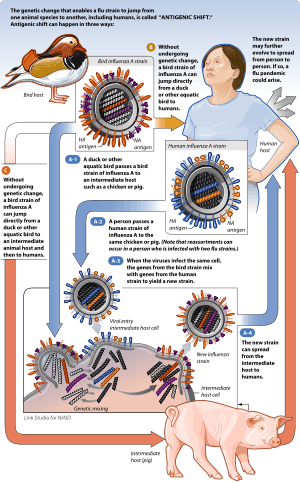

2009 A(H1N1) pandemic

In the 2009 flu pandemic, the virus isolated from patients in the United States was found to be made up of genetic elements from four different flu viruses – North American swine influenza, North American avian influenza, human influenza, and swine influenza virus typically found in Asia and Europe – "an unusually mongrelised mix of genetic sequences."[20] This new strain appears to be a result of reassortment of human influenza and swine influenza viruses, in all four different strains of subtype H1N1.

Preliminary genetic characterization found that the hemagglutinin (HA) gene was similar to that of swine flu viruses present in U.S. pigs since 1999, but the neuraminidase (NA) and matrix protein (M) genes resembled versions present in European swine flu isolates. The six genes from American swine flu are themselves mixtures of swine flu, bird flu, and human flu viruses.[21] While viruses with this genetic makeup had not previously been found to be circulating in humans or pigs, there is no formal national surveillance system to determine what viruses are circulating in pigs in the U.S.[22]

In April 2009, an outbreak of influenza-like illness (ILI) occurred in Mexico and then in the United States; the CDC reported seven cases of novel A/H1N1 influenza and promptly shared the genetic sequences on the GISAID database.[23][24] With similar timely sharing of data for Mexican isolates,[25] by April 24 it became clear that the outbreak of ILI in Mexico and the confirmed cases of novel influenza A in the southwest US were related and WHO issued a health advisory on the outbreak of "influenza-like illness in the United States and Mexico".[26] The disease then spread very rapidly, with the number of confirmed cases rising to 2,099 by May 7, despite aggressive measures taken by the Mexican government to curb the spread of the disease.[27] The outbreak had been predicted a year earlier by noticing the increasing number of replikins, a type of peptide, found in the virus.[28]

On June 11, 2009, the WHO declared an H1N1 pandemic, moving the alert level to phase 6, marking the first global pandemic since the 1968 Hong Kong flu.[29] On October 25, 2009, U.S. President Barack Obama officially declared H1N1 a national emergency[30] Despite President Obama's concern, a Fairleigh Dickinson University PublicMind poll found in October 2009 that an overwhelming majority of New Jerseyans (74%) were not very worried or not at all worried about contracting the H1N1 flu virus.[31] However, the President's declaration caused many U.S. employers to take actions to help stem the spread of the swine flu and to accommodate employees and / or workflow which may be impacted by an outbreak.[32]

A study conducted in coordination with the University of Michigan Health Service — scheduled for publication in the December 2009 American Journal of Roentgenology — warned that H1N1 flu can cause pulmonary embolism, surmised as a leading cause of death in this pandemic. The study authors suggest physician evaluation via contrast enhanced CT scans for the presence of pulmonary emboli when caring for patients diagnosed with respiratory complications from a "severe" case of the H1N1 flu.[33] However pulmonary embolism is not the only embolic manifestation of H1N1 infection. H1N1 may induce a number of embolic events such as myocardial infarction, bilateral massive DVT, arterial thrombus of infrarenal aorta, thrombosis of right external Iliac vein and common femoral vein or cerebral gas embolism. The type of embolic events caused by H1N1 infection are summarized in a recently published review by Dimitroulis Ioannis et al.[34]

The March 21, 2010 worldwide update, by the U.N.'s World Health Organization (WHO), states that "213 countries and overseas territories/communities have reported laboratory confirmed cases of pandemic influenza H1N1 2009, including at least 16,931 deaths."[35] As of May 30, 2010, worldwide update by World Health Organization(WHO) more than 214 countries and overseas territories or communities have reported laboratory confirmed cases of pandemic influenza H1N1 2009, including over 18,138 deaths.[36] The research team of Andrew Miller MD showed pregnant patients are at increased risk.[37] It has been suggested that pregnant women and certain populations such as native North Americans have a greater likelihood of developing a T helper type 2 response to H1N1 influenza which may be responsible for the systemic inflammatory response syndrome that causes pulmonary edema and death.[38]

On 26 April 2011, an H1N1 pandemic preparedness alert was issued by the World Health Organization for the Americas.[39] In August 2011, according to the U.S. Geological Survey and the CDC, northern sea otters off the coast of Washington state were infected with the same version of the H1N1 flu virus that caused the 2009 pandemic and "may be a newly identified animal host of influenza viruses".[40] In May 2013, seventeen people died during an H1N1 outbreak in Venezuela, and a further 250 were infected.[41] As of early January 2014, Texas health officials have confirmed at least thirty-three H1N1 deaths and widespread outbreak during the 2013/2014 flu season,[42] while twenty-one more deaths have been reported across the US. Nine people have been reported dead from an outbreak in several Canadian cities,[43] and Mexico reports outbreaks resulting in at least one death.[44] Spanish health authorities have confirmed 35 H1N1 cases in the Aragon region, 18 of whom are in intensive care.[45] On March 17, 2014, three cases were confirmed with a possible fourth awaiting results occurring at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.[46]

2015 India outbreak

Swine flu was reported in India in early 2015. The disease affected more than 31,000 people and claimed over 1,900 lives.[47]

2017 Maldives outbreak

Maldives reported swine flu in early 2017;[48] 501 people were tested for the disease and 185 (37%) of those tested were positive for the disease. Four of those who tested positive from these 185 died due to this disease.[49]

The total number of people who have died due to the disease is unknown. Patient Zero was never identified.[50]

Schools were closed for a week due to the disease, but were ordered by the Ministry of Education to open after the holidays even though the disease was not fully under control.[51]

After widespread rumors about Saudi Arabia going to purchase an entire atoll from Maldives, the Saudi Arabian embassy in Maldives issued a statement dismissing the rumors.[52][53] However, the trip of the Saudi monarch was going forward until it was cancelled later due to the H1N1 outbreak in Maldives.[54]

2017 Myanmar outbreak

Myanmar reported H1N1 in late July 2017. As of 27 July, there were 30 confirmed cases and six people had died.[55] The Ministry of Health and Sports of Myanmar sent an official request to WHO to provide help to control the virus; and also mentioned that the government would be seeking international assistance, including from the UN, China and the United States.[56]

2017–2018 Pakistan outbreak

Pakistan reported H1N1 cases mostly arising from the city of Multan, with deaths resulting from the epidemic reaching 42.[57] There have also been confirmed cases in cities of Gujranwala and Lahore.

2019 Outbreak in Malta

An outbreak of swine flu in the European Union member state was reported in mid-January 2019, with the island's main state hospital overcrowded within a week, with more than 30 cases being treated.[58]

2019 Outbreak in Morocco

In January 2019 an outbreak of H1N1 was recorded in Morocco, with nine confirmed fatalities.[59] As of February 4, 11 deaths have been reported in various regions of Morocco.

2019 Outbreak in Iran

In November 2019 an outbreak of H1N1 has been recorded in Iran, with 56 fatalities, most of them as a result of Dexamethasone injection, also 4000 people has been hospitalized.[60]

In pregnancy

Pregnant women who contract the H1N1 infection are at a greater risk of developing complications because of hormonal changes, physical changes and changes to their immune system to accommodate the growing fetus.[61] For this reason the Center for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that those who are pregnant to get vaccinated to prevent the influenza virus. The vaccination should not be taken by people who have had a severe allergic reaction to the influenza vaccination. Additionally those who are moderately to severely ill, with or without a fever should wait until they recover before taking the vaccination.[62]

Pregnant women who become infected with the influenza are advised to contact their doctor immediately. Influenza can be treated using antiviral medication, which are available by prescription. Oseltamivir (trade name Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza) are two neuraminidase inhibitors (antiviral medications) currently recommended. It has been shown that they are most effective when taken within two days of becoming sick.[63]

Since October 1, 2008, the CDC has tested 1,146 seasonal influenza A (H1N1) viruses for resistance against oseltamivir and zanamivir. It was found that 99.6% of the samples were resistant to oseltamivir while none were resistant to zanamivir. In 853 samples of 2009 Influenza A (H1N1) virus only 4% showed resistance to oseltamivir, while none of 376 samples showed resistance to zanamivir.[64] A study conducted in Japan during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic concluded that infants exposed to either oseltamivir or zanamivir had no short term adverse effects.[65] Both amantadine and rimantadine have been found to be teratogenic and embryotoxic (malformations and toxic effects on the embryo) when given at high doses in animal studies.[66]

Additional images

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to H1N1 influenza. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to H1N1 influenza subtype influenza A virus. |

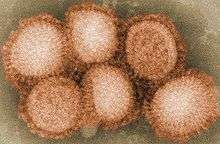

This colorized transmission electron micrograph shows H1N1 influenza virus particles. Surface proteins on the virus particles are shown in black

This colorized transmission electron micrograph shows H1N1 influenza virus particles. Surface proteins on the virus particles are shown in black This colorized transmission electron micrograph shows H1N1 influenza virus particles.

This colorized transmission electron micrograph shows H1N1 influenza virus particles.

Notes

- Boon, Lim (23 September 2011). "Influenza A H1N1 2009 (Swine Flu) and Pregnancy". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 61 (4): 386–393. doi:10.1007/s13224-011-0055-2. PMC 3295877. PMID 22851818.

- "Influenza Summary Update 20, 2004–2005 Season". FluView: A Weekly Influenza Surveillance Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Roos R (10 August 2010). "WHO says H1N1 pandemic is over". CIDRAP. Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, University of Minnesota.

- Dhama, Kuldeep (2012). "Swine Flu is back again". Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences. 15 (21): 1001–1009. doi:10.3923/pjbs.2012.1001.1009. PMID 24163942.

- "Humans May Give Swine Flu To Pigs In New Twist To Pandemic". Sciencedaily.com. 2009-07-10. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- Kobasa D, Jones SM, Shinya K, et al. (January 2007). "Aberrant innate immune response in lethal infection of macaques with the 1918 influenza virus". Nature. 445 (7125): 319–23. Bibcode:2007Natur.445..319K. doi:10.1038/nature05495. PMID 17230189.

- Kash JC, Tumpey TM, Proll SC, et al. (October 2006). "Genomic analysis of increased host immune and cell death responses induced by 1918 influenza virus". Nature. 443 (7111): 578–81. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..578K. doi:10.1038/nature05181. PMC 2615558. PMID 17006449.

- Cheung CY, Poon LL, Lau AS, et al. (December 2002). "Induction of proinflammatory cytokines in human macrophages by influenza A (H5N1) viruses: a mechanism for the unusual severity of human disease?". Lancet. 360 (9348): 1831–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11772-7. PMID 12480361.

- Palese P (December 2004). "Influenza: old and new threats". Nat. Med. 10 (12 Suppl): S82–7. doi:10.1038/nm1141. PMID 15577936.

- Barry, John M. (2004). The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Greatest Plague in History. Viking Penguin. ISBN 978-0-670-89473-4.

- Gaydos JC, Top FH, Hodder RA, Russell PK (January 2006). "Swine influenza a outbreak, Fort Dix, New Jersey, 1976". Emerging Infect. Dis. 12 (1): 23–8. doi:10.3201/eid1201.050965. PMC 3291397. PMID 16494712.

- "Pandemic H1N1 2009 Influenza". CIDRAP. Center for Infectious Disease Research & Policy, University of Minnesota. Retrieved 2011-07-30.

- "1977 Russian Flu Pandemic". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- "Origin of current influenza H1N1 virus". virology blog. 2 March 2009. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- "New Strain May Edge Out Seasonal Flu Bugs". NPR. 4 May 2009. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- "Interactive health timeline box 1977: Russian flu scare". CNN. Archived from the original on March 22, 2007.

- "Invasion from the Steppes". Time magazine. February 20, 1978.

- "Pandemic Influenza: Recent Pandemic Flu Scares". Global Security.

- "Russian flu confirmed in Alaska". State of Alaska Epidemiology Bulletin (9). April 21, 1978.

- "Deadly new flu virus in US and Mexico may go pandemic". New Scientist. 2009-04-26. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- Susan Watts (2009-04-25). "Experts concerned about potential flu pandemic". BBC.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (April 2009). "Swine influenza A (H1N1) infection in two children—Southern California, March–April 2009". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 58 (15): 400–2. PMID 19390508.

- "Viral gene sequences to assist update diagnostics for swine influenza A(H1N1)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 15, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Butler, Declan (2009-04-27). "Swine flu outbreak sweeps the globe". Nature News. doi:10.1038/news.2009.408.

- "Influenza cases by a new sub-type: Regional Update". Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Epidemiological Alerts Vol. 6, No. 15. 29 April 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Influenza-like illness in the United States and Mexico". Disease Outbreak News. World Health Organization. 2009-04-24. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- "Influenza A(H1N1) — update 19". Disease Outbreak News. World Health Organization. 2009-05-07. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- "Efforts To Quickly Develop Swine Flu Vaccine". Science Daily. June 4, 2009. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

One company, Replikins, actually predicted over a year ago that significant outbreaks of the H1N1 flu virus would occur within 6-12 months.

- "H1N1 Pandemic – It's Official". 2009-06-11. Archived from the original on 2009-06-15.

- "Obama declares swine flu a national emergency". The Daily Herald. 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-26.

- "New Jerseyans Not Worried About H1N1" (PDF). Publicmind.fdu.edu. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "The Arrival of H1N1 Influenza: Legal Considerations and Practical Suggestions for Employers". The National Law Review. Davis Wright Tremaine, LLP. 2009-11-02. Retrieved 2011-11-03.

- Mollura DJ, Asnis DS, Crupi RS, et al. (December 2009). "Imaging Findings in a Fatal Case of Pandemic Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1)". AJR Am J Roentgenol. 193 (6): 1500–3. doi:10.2214/AJR.09.3365. PMC 2788497. PMID 19933640.

- Dimitroulis I, Katsaras M, Toumbis (October 2010). "H1N1 infection and embolic events. A multifaceted disease". Pneumon. 29 (3): 7–13.

- "Situation updates – Pandemic (H1N1) 2009". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- "Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 – update 103". Disease Outbreak News. World Health Organization. 2010-06-04. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- "H1N1 Pandemic Flu Hits Pregnant Women Hard". Businessweek.com. 2010-05-24. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- McAlister VC (October 2009). "H1N1-related SIRS?". CMAJ. 181 (9): 616–7. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-2028. PMC 2764762. PMID 19858268. Archived from the original on 2011-05-11.

- "WHO Issues H1N1 Pandemic Alert". Recombinomics.com. April 26, 2011.

- Rogall, Gail Moede (2014-04-08). "Sea Otters Can Get the Flu, Too". U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- "H1N1 flu outbreak kills 17 in Venezuela: media". Reuters. 27 May 2013.

- "North Texas confirmed 20 flu deaths - Xinhua". English.news.cn. Archived from the original on 2014-01-12.

- "9 deaths caused by H1N1 flu in Alberta". Cbc.ca. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "Un muerto en Coahuila por influenza AH1N1". Vanguardia.com.mx.

- "Aumentan a 35 los hospitalizados por gripe A en Aragón". Cadenaser.com. 12 January 2014.

- "Three cases of H1N1 reported at CAMH - The Star". Thestar.com. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "Swine Flu Toll Inches Towards 1,900; Number of Cases Cross 31,000". NDTV.com. 19 March 2015.

- "Makeshift flu clinics swamped as H1N1 cases rise to 82". Maldives Independent.com.

- "Breaking: Swine flu gai Ithuru meehaku maruve, ithuru bayaku positive vejje". Mihaaru.com.

- "H1N1 death toll rises to three". Maldives Independent.com.

- "Schools to open after flu outbreak". Maldives Independent.com.

- Ankit Panda. "Will Saudi Arabia Purchase an Entire Atoll From the Maldives?". Thediplomat.com.

- "Maldives dismisses claims Saudi Arabia buying atoll". Arabnews.com. 11 March 2017.

- "Saudi king cancels Maldives trip, citing swine flu". Presstv.ir.

- Lone, Wa; Lewis, Simon (27 July 2017). "Myanmar tracks spread of H1N1 as outbreak claims sixth victim". Reuters. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- Htet Naing Zaw (27 July 2017). "Myanmar Asks WHO to Help Fight H1N1 Virus". The Irrawaddy. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- "Toll rises to 42 as 3 more succumb to swine flu". The Nation. 24 January 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Caruana, Claire; Xuereb, Matthew (18 January 2019). "Swine flu outbreak at Mater Dei hospital, St Vincent de Paul". Times of Malta. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- "Swine flu outbreak kills 9 in Morocco". Al Arabiya. AFP. 2 February 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- www.yjc.ir https://www.yjc.ir/fa/news/7155842/%D8%A2%D9%86%D9%81%D9%88%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%B2%D8%A7-%D9%88-%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%87%E2%80%8C%D9%87%D8%A7%DB%8C-%D8%AF%D8%B1%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%A2%D9%86-%D8%B1%D8%A7-%D8%A8%D8%B4%D9%86%D8%A7%D8%B3%DB%8C%D8%AF. Retrieved 2019-12-03. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Boon, Lim (September 23, 2011). "Influenza A H1N1 2009 (Swine Flu) and Pregnancy". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of India. 61 (4): 389–393. doi:10.1007/s13224-011-0055-2. PMC 3295877. PMID 22851818.

- "Key Facts about Seasonal Flu Vaccine". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- "What You Should Know About Flu Antiviral Drugs". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- "2008-2009 Influenza Season Week 32 ending August 15, 2009". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- Saito, S; Minakami, H; Nakai, A; Unno, N; Kubo, T; Yoshimura, Y (Aug 2013). "Outcomes of infants exposed to oseltamivir or zanamivir in utero during pandemic (H1N1) 2009". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 209 (2): 130.e1–9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.04.007. PMID 23583838.

- "Pandemic OBGYN". Sarasota Memorial Health Care System. Archived from the original on 2014-02-03. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to H1N1 virus |

| Wikinews has related news: Swine flu cases worldwide top 1,000 |

- European Commission – Public Health EU Coordination on Pandemic (H1N1) 2009.

- Health-EU Portal EU work to prepare a global response to influenza A(H1N1).

- Influenza Research Database Database of influenza genomic sequences and related information.

- Centers For Disease Control and Prevention H1N1 Flu (Swine Flu).

- Consultant Magazine H1N1 (Swine Flu) Center

- Pandemic Influenza: A Guide to Recent Institute of Medicine Studies and Workshops A collection of research papers and summaries of workshops by the Institute of Medicine on major policy issues related to pandemic influenza and other infectious disease threats.

- H1N1 Flu, 2009: Hearings before the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, United States Senate, of the One Hundred Eleventh Congress, First Session: April 29, 2009, Coordinating the Federal Response; September 21, 2009, Protecting Our Community: Field Hearing in Hartford, CT; October 21, 2009, Monitoring the Nation's Response; November 17, 2009, Getting the Vaccine to Where It is Most Needed.

Nontechnical

- Shreeve, J. (29 January 2006). "Why Revive a Deadly Flu Virus?". New York Times. Six-page human-interest story on the recreation of the deadly 1918 H1N1 flu virus

- "1918 flu virus's secrets revealed". BBC News. 28 September 2006. Results from analyzing a recreated strain.

- Noymer, A. (September 2005). "Some information on TB and the 1918 flu". Data from Noymer A, Garenne M (2000). "The 1918 influenza epidemic's effects on sex differentials in mortality in the United States". Popul Dev Rev. 26 (3): 565–81. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2000.00565.x. PMC 2740912. PMID 19530360.

- Oral history by 1918 pandemic survivor

Technical

- Ludwig S, Haustein A, Kaleta EF, Scholtissek C (July 1994). "Recent influenza A (H1N1) infections of pigs and turkeys in northern Europe". Virology. 202 (1): 281–6. doi:10.1006/viro.1994.1344. PMID 8009840.

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (February 1987). "Influenza A(H1N1) associated with mild illness in a nursing home–Maine". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 36 (4): 57–9. PMID 3100930.

- Lederberg J (February 2001). "H1N1-influenza as Lazarus: Genomic resurrection from the tomb of an unknown". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (5): 2115–6. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.2115L. doi:10.1073/pnas.051000798. PMC 33382. PMID 11226198.

- H1N1 Registry (ESICM – European Society of Intensive Care Medicine)