Gut-associated lymphoid tissue

Gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT)[1] is a component of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) which works in the immune system to protect the body from invasion in the gut.

| Gut-associated lymphoid tissue | |

|---|---|

| Details | |

| System | Lymphatic system |

| Identifiers | |

| Acronym(s) | GALT |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Owing to its physiological function in food absorption, the mucosal surface is thin and acts as a permeable barrier to the interior of the body. Equally, its fragility and permeability creates vulnerability to infection and, in fact, the vast majority of the infectious agents invading the human body use this route.[2] The functional importance of GALT in body's defense relies on its large population of plasma cells, which are antibody producers, whose number exceeds the number of plasma cells in spleen, lymph nodes and bone marrow combined.[3]

Structure

The gut-associated lymphoid tissue lies throughout the intestine, covering an area of approximately 260–300 m2.[4] In order to increase the surface area for absorption, the intestinal mucosa is made up of finger-like projections (villi), covered by a monolayer of epithelial cells, which separates the GALT from the lumen intestine and its contents. These epithelial cells are covered by a layer of glycocalyx on their luminal surface so as to protect cells from the acid pH.

New epithelial cells derived from stem cells are constantly produced on the bottom of the intestinal glands, regenerating the epithelium (epithelial cell turnover time is less than one week).[2][5] Although in these crypts conventional enterocytes are the dominant type of cells, Paneth cells can also be found. These are located at the bottom of the crypts and release a number of antibacterial substances, among them lysozyme, and are thought to be involved in the control of infections.

Underneath them, there is an underlying layer of loose connective tissue called lamina propria. There is also lymphatic circulation through the tissue connected to the mesenteric lymph nodes.

Both GALT and mesenteric lymph nodes are sites where the immune response is started due to the presence of immune cells through the epithelial cells and the lamina propria.

The GALT also includes the Peyer's patches of the small intestine, isolated lymphoid follicles present throughout the intestine and the appendix in humans.[2]

The following comprise lymphoid tissue in the gut:

- Waldeyer's tonsillar ring

- Peyer's patches

- Lymphoid aggregates in the appendix and large intestine

- Lymphoid tissue accumulating with age in the stomach

- Small lymphoid aggregates in the esophagus

- Diffusely distributed lymphoid cells and plasma cells in the lamina propria of the gut

Peyer's patches

The Peyer's patch is an aggregate of lymphoid cells projected to the lumen of the gut which acts as a very important site for the initiation of the immune response. It forms a subepithelial dome where large number of B cell follicles with its germinal centers, T cells areas between them in a smaller number and dendritic cells are found. In this area, the subepithelial dome is separated from the intestinal lumen by a layer of follicle-associated epithelium. This contains conventional intestinal epithelial cells and a small number of specialized epithelial cells called microfold cells (M cells) in between. Unlike enterocytes, these M cells present a folded luminal surface instead of the microvilli, do not secrete digestive enzymes or mucus and lack a thick surface of glycocalix.

Function

The digestive tract is an important component of the body's immune system. In fact, the intestine possesses the largest mass of lymphoid tissue in the human body.[6] The GALT is made up of several types of lymphoid tissue that store immune cells, such as T and B lymphocytes, that carry out attacks and defend against pathogens.

New research indicates that GALT may continue to be a major site of HIV activity, even if drug treatment has reduced HIV count in the peripheral blood.[7][8]

Other animals

The adaptive immunity, mediated by antibodies and T cells, is only found in vertebrates. Whereas all of them have a gut-associated lymphoid tissue and the vast majority have a version of spleen and thymus, not all vertebrates show bone marrow, lymph nodes or germinal centers, what means that not all vertebrates can generate lymphocytes in bone marrow.[3] This different distribution of the adaptive organs in the different groups of vertebrates suggests GALT as the very first part of the adaptive immune system in vertebrates. It has been suggested that from this existing GALT, and due to the pressure put by commensal bacteria in gut that coevolved with vertebrates, later specializations as thymus, spleen or lymph nodes appeared as part of the adaptive immune system.[2]

Additional images

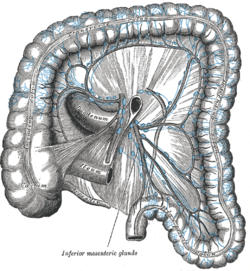

Lymphatics of colon.

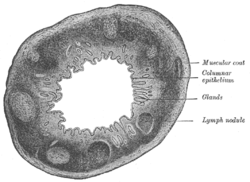

Lymphatics of colon. Section of the human esophagus.

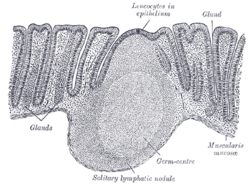

Section of the human esophagus. Transverse section of human vermiform process. X 20.

Transverse section of human vermiform process. X 20. Section of mucous membrane of human rectum. X 60.

Section of mucous membrane of human rectum. X 60.

References

- Janeway, CA Jr.; et al. (2001). "The mucosal immune system". Immunobiology. New York: Garland Science. 10-13. ISBN 978-0-8153-3642-6.

- Murphy, K. (2011). Janeway's immunobiology (Immunobiology: The Immune System (Janeway)). Garland Science. ISBN 9780815342434. OCLC 733935898.

- Goldsby, R. A.; Osborne, B. A.; Kindt, T. J.; Kuby, J. (2007-01-01). Kuby immunology. W.H. Freeman. ISBN 9780716767640. OCLC 68207318.

- Helander, Herbert F.; Fändriks, Lars (2014-06-01). "Surface area of the digestive tract – revisited". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 49 (6): 681–689. doi:10.3109/00365521.2014.898326. ISSN 0036-5521. PMID 24694282.

- Slomianka, Lutz. "Blue Histology - Gastrointestinal Tract". www.lab.anhb.uwa.edu.au. Retrieved 2017-01-30.

- Salminen S, Bouley C, Boutron-Ruault MC, et al. (1998). "Functional food science and gastrointestinal physiology and function". British Journal of Nutrition. 80 (S1): S147–S171. doi:10.1079/BJN19980108.

- Moraima Guadalupe,1 Sumathi Sankaran,1 Michael D. George,1 Elizabeth Reay,1 David Verhoeven,1 Barbara L. Shacklett,1 Jason Flamm,4 Jacob Wegelin,3 Thomas Prindiville,2 and Satya Dandekar. Viral Suppression and Immune Restoration in the Gastrointestinal Mucosa of HIV Type 1-Infected Patients Initiating Therapy during Primary or Chronic Infection Journal of Virology, August 2006, p. 8236-8247, Vol. 80, No. 16

- Anton PA, Mitsuyasu RT, Deeks SG, Scadden DT, Wagner B, Huang C, Macken C, Richman DD, Christopherson C, Borellini F, Lazar R, Hege KM. Multiple measures of HIV burden in blood and tissue are correlated with each other but not with clinical parameters in aviremic subjects. AIDS. 2003 Jan 3;17(1):53-63.

External links

- Histology image: 12502loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - "Digestive System: Alimentary Canal: colon, taenia coli"

- Histology image: 11102loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - "Digestive System: Alimentary Canal: esophageal/stomach junction"