Gray's Anatomy

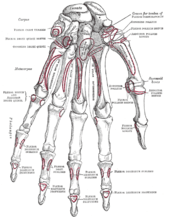

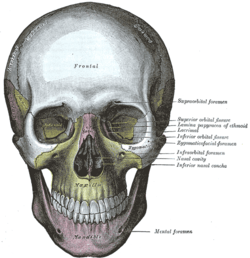

Gray's Anatomy is an English written textbook of human anatomy originally written by Henry Gray and illustrated by Henry Vandyke Carter. Earlier editions were called Anatomy: Descriptive and Surgical, Anatomy of the Human Body and Gray's Anatomy: Descriptive and Applied, but the book's name is commonly shortened to, and later editions are titled, Gray's Anatomy. The book is widely regarded as an extremely influential work on the subject, and has continued to be revised and republished from its initial publication in 1858 to the present day. The latest edition of the book, the 41st, was published in September 2015.

-_Title_page.png) Title page of American 20th edition (1918) | |

| Author | Henry Gray |

|---|---|

| Original title | Anatomy: Descriptive and Surgical |

| Illustrator | Henry Vandyke Carter |

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Human anatomy |

Publication date | 1858 |

Publication history

Origins

The English anatomist Henry Gray was born in 1827. He studied the development of the endocrine glands and spleen and in 1853 was appointed Lecturer on Anatomy at St George's Hospital Medical School in London. In 1855, he approached his colleague Henry Vandyke Carter with his idea to produce an inexpensive and accessible anatomy textbook for medical students. Dissecting unclaimed bodies from workhouse and hospital mortuaries through the Anatomy Act of 1832, the two worked for 18 months on what would form the basis of the book. Their work was first published in 1858 by John William Parker in London.[1] It was dedicated by Gray to Sir Benjamin Collins Brodie, 1st Baronet.

An imprint of this English first edition was published in the United States in 1859, with slight alterations.[2][3] Gray prepared a second, revised edition, which was published in the United Kingdom in 1860, also by J.W. Parker.[4][5] However, Gray died the following year, at the age of 34, having contracted smallpox[4] while treating his nephew (who survived). His death had come just three years after the initial publication of his Anatomy Descriptive and Surgical. Even so, the work on his much-praised book was continued by others.[6]

Longman's publication reportedly began in 1863, after their acquisition of the J.W. Parker publishing business.[7] This coincided with the publication date of the third British edition of Gray's Anatomy.[8] Successive British editions of Gray's Anatomy continued to be published under the Longman, and more recently Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier imprints, reflecting further changes in ownership of the publishing companies over the years.

American editions

The full American rights were purchased by Blanchard and Lea, who published the first of twenty-five[lower-alpha 1] distinct American editions of Gray's Anatomy in 1862, and whose company became Lea & Febiger in 1908. Lea & Febiger continued publishing the American editions until the company was sold in 1990.[9]

The first American publication was edited by Richard James Dunglison, whose father Robley Dunglison was physician to Thomas Jefferson.[10] Dunglison edited the next four editions. These were: the Second American Edition (February 1862); the New Third American from the Fifth English Edition (May 1870); the New American from the Eighth English Edition (July 1878); and the New American from the Tenth English Edition (August 1883). W. W. Keen edited the next two editions, namely: the New American from the Eleventh English Edition (September 1887); and the New American from the Thirteenth English Edition (September 1893).

In September 1896, reference to the English edition was dropped and it was published as the Fourteenth Edition, edited by Bern B. Gallaudet, F. J. Brockway, and J. P. McMurrich, who also edited the Fifteenth Edition (October 1901). There is also an edition dated 1896 which does still reference the English edition stating it is "A New Edition, Thoroughly Revised by American Authorities, from the thirteenth English Edition" and edited by T. Pickering Pick, F.R.C.S. and published by Lea Brothers & Co., Philadelphia and New York.[11]

The Sixteenth Edition (October 1905) was edited by J. C. DaCosta, and the Seventeenth (September 1908) by DaCosta and E. A. Spitzka. Spitzka edited the Eighteenth (Oct. 1910) and Nineteenth (July 1913) editions, and in October 1913, R. Howden edited the New American from the Eighteenth English Edition. The "American" editions then continued with consecutive numbering from the Twentieth onwards, with W. H. Lewis editing the 20th (September. 1918), 21st (August 1924), 22nd (August 1930), 23rd (July 1936), and 24th (May 1942). Charles Mayo Goss edited the 25th (August 1948), 26th (July 1954), 27th (August 1959), 28th (August 1966), and 29th (January 1973). Carmine D. Clemente edited and extensively revised the 30th edition (October 1984).[12] With the sale of Lea & Febiger in 1990, the 30th edition was the last American Edition.

Discrepancies in numbering of American and British editions

Sometimes separate editing efforts with mismatches between British and American edition numbering led to the existence, for many years, of two main "flavours" or "branches" of Gray's Anatomy: the U.S. and the British one. This can easily cause misunderstandings and confusion, especially when quoting from or trying to purchase a certain edition. For example, a comparison of publishing histories shows that the American numbering kept roughly apace with the British up until the 16th editions in 1905, with the American editions either acknowledging the English edition, or simply matching the numbering in the 14th, 15th and 16th editions. Then the American numbering crept ahead, with the 17th American edition published in 1908, while the 17th British edition was published in 1909. This increased to a three-year gap for the 18th and 19th editions, leading to the 1913 publication of the New American from the Eighteenth English, which brought the numbering back into line. Both 20th editions were then published in the same year (1918). Thereafter, it was the British numbering that pushed ahead, with the 21st British edition in 1920, and the 21st American edition in 1924. This discrepancy continued to increase, so that the 30th British edition was published in 1949, while the 30th and last American edition was published in 1984.[8][13]

Currently available editions

The newest, 41st edition of Gray's Anatomy was published on 25 September 2015 by Elsevier in both print and online versions, and is the first edition to have enhanced online content including anatomical videos and a bonus Gray's imaging library. The 41st edition also has 24 specially invited online commentaries on contemporary anatomical topics such as advances in electron and fluorescent microscopy; the neurovascular bundles of the prostate; stem cells in regenerative medicine; the anatomy of facial aging; and technical aspects and applications of diagnostic radiology.

The senior editor of this book and accompanying website on ExpertConsult [14] is Professor Susan Standring, who is Emeritus Professor of Anatomy at King's College London.[15] The three most recent editions differ from all previous editions in an important aspect: they present anatomical structures by their regional anatomy (i.e. ordered according to what part of the body the structures are located in – e.g. the anatomy of the bones, blood vessels and nerves, etc. of the upper extremity is described in one place). All editions of Gray's Anatomy previous to the 39th were organized by systemic anatomy (i.e. there were separate sections for the body's entire skeletal system, entire circulatory system and entire nervous system, etc.). The editors of the 39th edition acknowledged the validity of both approaches but switched to regional anatomy by popular demand.[16]

Older, out-of-copyright editions of the book continue to be reprinted and sold, particularly on the internet. However it is not always clear which (British or American) edition these books are republications of. Many seem to be reprints of the 1901 (probably U.S.) edition. Additionally, there are several sites where various older versions can be read online.[17][18][19] Although older editions may serve historic and artistic uses because their companion illustrations and anatomical cross sections are renowned for their rustic and often haunting presentation, they may no longer represent an up-to-date understanding of human anatomy.[lower-alpha 2]

Henry Gray wrote Gray's Anatomy with an audience of medical students and physicians in mind, especially surgeons. For many decades however, precisely because Gray's textbook became such a classic, successive editors made major efforts to preserve its position as possibly the most authoritative text on the subject in English. Toward this end, a long-term strategy appears to have been to make each edition come close to containing a fully comprehensive account of the anatomical medical understanding available at the time of publication. Given the explosion of medical knowledge in the 20th century, it is easily appreciated that this led to a vast expansion of the book, which threatened to collapse under its own weight in a metaphorical and physical sense. From the 35th edition onward, increased efforts were made to reverse this trend and keep the book readable by students. Nevertheless, the 38th edition contained 2,092 pages in large format[20] – the highest page count of any and an increase from the 35th edition, which had 1,471 pages.[21] The current 41st edition has 1,584 pages. Newer editions of Gray's Anatomy – and even several recent older ones – are still considered to be the most comprehensive and detailed textbooks on the subject.[22] Despite previous efforts to keep Gray's Anatomy readable by students, when the 39th edition was published, students were identified as a secondary market for the book,[23] and companion publications such as Gray's Anatomy for Students,[lower-alpha 3] Gray's Atlas of Anatomy and Gray's Anatomy Review have also been published in recent years.[24]

Cultural influence

In Mark Twain's The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, the book that Tom catches Becky Thatcher reading, and from which she tears a page, is implied to be Gray's Anatomy.

In Bette Bao Lord’s 1984 book "In the Year of the Boar and Jackie Robinson", Shirley Temple Wong and her new friend Emily secretly look at the "naked people" in "Gray’s Anatomy".

Early in the 1970 Tamil film Malathi, medical students Gemini Ganesan and B. Saroja Devi try to obtain the 28th edition of Gray's Anatomy from an old book shop.

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s art was inspired by the book’s illustrations since it was read by him many times when he was a child, especially when recovering from an accident he suffered.[25]

In the 1991 movie The Addams Family Granny (Judith Malina) reads Gray's Anatomy while Gomez (Raul Julia) is playing with his train sets.

The 1996 Steven Soderbergh film Gray's Anatomy, featuring monologuist Spalding Gray, also takes its name from the title of the book, as does Gray's Anatomy: Selected Writings, a 2009 book by British political philosopher John N. Gray.

In the 1998 Star Trek: Voyager episode "Message in a Bottle", the new Emergency Medical Hologram designed by Ensign Kim begins reciting the contents of Gray's Anatomy when activated, beginning with a description of the cell.

The American medical drama Grey's Anatomy (2005 –) is a play on words referring to both the textbook and the name of the series' lead character.[26][27][28][29]

The name of Jim Leonard Jr.'s 2006 play Anatomy of Gray, which centers on a doctor visiting a small town in Indiana in 1880, takes its title as a play on Gray's Anatomy.

In Dan Brown's 2013 novel Inferno, Sienna Brooks, as a child, reads all 1,600 pages of Gray's Anatomy in ten days.

In the ABC television series The Good Doctor (2017–present), the lead character, Dr. Shaun Murphy, an autistic savant, often visualizes illustrations from Gray's Anatomy as he mentally diagnoses a patient's condition.

Notes

- This count excludes the previously mentioned 1859 US publication of the English first edition.

- Depending on the version at hand, even the suitability of reprints and online versions for artistic purposes may be compromised due to limitations in resolution and reproduction quality.

- Written by Richard L. Drake, Wayne Vogl and Adam W. M. Mitchell

The Sternocleidomastoid is missing from the depiction of the Phrenic Nerve and surrounding muscles in both illustrations given of the Phrenic Nerve and surrounding muscles in H. V. Carters illustration from Henry Gray's Anatomy of the Human Body used in the Wikipedia's depiction of the Phrenic Nerve and surrounding muscles.

Missing Sternocleidomastoid first noticed and edited: 2019 on Wikipedia by myself James Robert Leedham Clegg. Anatomy, Physiology and Pathology Dip. 2009. Born in Pitsmoor, Sheffield, England on 12th August, 1983-still living.

References

- Gray, Henry; Carter, Henry Vandyke (1858), Anatomy Descriptive and Surgical, London: John W. Parker and Son, retrieved 16 October 2011

- Richardson, Ruth (2005), "A Historical Introduction to Gray's Anatomy" (PDF), in Susan Standring (ed.), Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (39th (electronic version) ed.), Edinburgh: Elsevier Churchill Livingston, p. 4, retrieved 16 October 2011

- Gray, Henry; Carter, H.V (1859), Anatomy, descriptive and surgical, Philadelphia: Blanchard and Lea, retrieved 16 October 2011(Per National Library of Medicine holdings). Note: This is not the 'American' edition. American rights had yet to be purchased. It is an American publication of the English edition.

- Moore, Wendy (30 March 2008), "Gray's Anatomy celebrates 150th anniversary", The Telegraph, Telegraph Media Group, retrieved 16 October 2011

- A brief history of Gray's Anatomy (PDF), ElsevierHealth, retrieved 16 October 2011

- Poynter, F. N. L. (6 September 1958). "Gray's Anatomy: The First Hundred Years" (PDF). British Medical Journal: 610–11.

- "Longman's 1863 publication of Gray's Anatomy", Pearson Education: History, Pearson Education, archived from the original on 9 March 2012, retrieved 16 October 2011

- Warwick, Roger; Williams, Peter L., eds. (1973), Gray's Anatomy (35th ed.), London: Longman p. iv (Previous Editions and Editors – listings)

- Lea & Febiger in Tredyffrin East Town Historical Society History Quarterly Digital Archives, pp. 68–70 (Source: April 1999, Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 63–70)

- "Gray's Anatomy: The Jefferson Years" in Jeffline Forum, September 2003

- Gray, Henry Gray's Anatomy Descriptive and Surgical, 1896 13th edition

- Carmine D. Clemente, ed. (1985), Gray's Anatomy (30th ed.), Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, ISBN 0-8121-0644-X pp. vi–ix

- Carmine D. Clemente (1985) p. vi (American Editions of Gray's Anatomy – listings)

- Inkling. "Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice by Susan Standring". Expert Consult (eBook).

- Elsevier: Gray's Anatomy, 41st Edition

- Gray's Anatomy vol.39e Introduction (PDF), 2004, ISBN 0-443-06676-0, retrieved 21 March 2012See p. 9, bottom

- Henry Gray. "Anatomy, descriptive and surgical". Open Library. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- "Gray, Henry. 1918. Anatomy of the Human Body". Bartleby.com. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- "Gray's Anatomy". Education.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Medicine and Surgery (British Edition. 38th Ed) (Hardcover) Amazon

- Description of 35th Edition (1973) at WorldCat Retrieved 21 March 2012

- 'Gray's Anatomy' is back after major surgery, By Glenn O'Neal, Posted 4/10/2005, USATODAY.com USA Today

- "cf. page 11".

- "US Elsevier Health Bookshop". www.us.elsevierhealth.com.

- Laing, Olivia (8 September 2017). "Race, power, money – the art of Jean-Michel Basquiat". the Guardian. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- Roschke, Ryan (30 November 2017). "In Case You Didn't Know, This Is How Grey's Anatomy Got Its Title". PopSugar.

- Standring, Susan (November 2005). "Gray’s Anatomy, 39th Edition: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice". American Journal of Neuroradiology. 26 (10) 2703-2704.

- Holtz, Andrew (5 January 2010). The Real Grey's Anatomy: A Behind-the-Scenes Look at the Real Lives of Surgical Residents. "Introduction". Penguin. Google Books. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- Horbury, Alison (28 July 2015). Post-feminist Impasses in Popular Heroine Television: The Persephone Complex. Palgrave Macmillan. Google Books. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

Bibliography

- Gray, Henry (1858), Anatomy: Descriptive and Surgical, London: John W. Parker and Son, OL 24780759MOnline- and PDF versions of the 1st edition at Open Library/Internet Archive. Several other editions are also available at this site.

- Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (40th ed.), Churchill-Livingstone, Elsevier, 2008, ISBN 978-0-443-06684-9

- Richardson, Ruth (2005), "A Historical Introduction to Gray's Anatomy" (PDF), in Susan Standring (ed.), Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (39th (electronic version) ed.), Edinburgh: Elsevier Churchill Livingston, retrieved 16 October 2011, A brief history of the British Edition of the book.

- Richardson, Ruth (2008), The Making of Mr. Gray's Anatomy, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-955299-3

- Hayes, Bill (2007), The Anatomist: a True story of Gray's Anatomy, Ballantine, ISBN 978-0-345-45689-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gray's Anatomy plates. |

- Online version of Gray's Anatomy — The complete 20th U.S. edition of Gray's Anatomy of the Human Body, published in 1918. NB: This is the most recent American version that is in the public domain.

- Online audio recording of the text of the same edition in five parts: 12345

- First edition of Gray's Anatomy, 1858 (direct PDF link)

- Gray's Anatomy. 2014. Episode 5 of the BBC TV series The Beauty of Anatomy.

- Video of @Google Talk by Bill Hayes on Gray's Anatomy

- Selected images from the 1st edition of Gray's Anatomy From The College of Physicians of Philadelphia Digital Library

- Gray's Anatomy for students in libraries (WorldCat catalog)