Adhesive capsulitis of shoulder

Adhesive capsulitis is a painful and disabling disorder of unclear cause in which the shoulder capsule, the connective tissue surrounding the glenohumeral joint of the shoulder, becomes inflamed and stiff, greatly restricting motion and causing chronic pain. Pain is usually constant, worse at night, and with cold weather. Certain movements or bumps can provoke episodes of tremendous pain and cramping. The condition is thought to be caused by injury or trauma to the area and may have an autoimmune component.

| Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Frozen shoulder |

| |

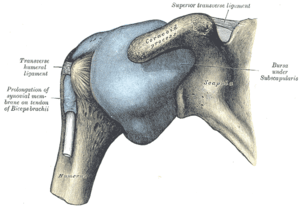

| The right shoulder & glenohumeral joint. | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Pain, stiffness, restricted movement[1] |

Risk factors for frozen shoulder include tonic seizures, diabetes mellitus, stroke, accidents, lung disease, connective tissue diseases, thyroid disease, and heart disease. It is more prevalent in people 40–65 years of age, and in females.[1] Treatment may be painful and taxing and consists of physical therapy, occupational therapy, medication, massage therapy, hydrodilatation or surgery. A physician may also perform manipulation under anesthesia, which breaks up the adhesions and scar tissue in the joint to help restore some range of motion. Alternative treatments exist such as the Trigenics OAT Procedure, ART, and the OTZ method. But these can vary in efficacy depending on the type and severity of the frozen shoulder. Pain and inflammation can be controlled with analgesics and NSAIDs. Steroid injection alone is only a short term benefit in alleviating pain.[2]

People who have adhesive capsulitis usually experience severe pain and sleep deprivation for prolonged periods due to pain that gets worse when lying still and restricted movement/positions. The condition can lead to depression, problems in the neck and back, and severe weight loss due to long-term lack of deep sleep. People who have adhesive capsulitis may have difficulty concentrating, working, or performing daily life activities for extended periods of time. The condition tends to be self-limiting and usually resolves over time without surgery. Most people regain about 90% of shoulder motion over time.

Signs and symptoms

Movement of the shoulder is severely restricted, with progressive loss of both active and passive range of motion.[3] The condition is sometimes caused by injury, leading to lack of use due to pain, but also often arises spontaneously with no obvious preceding trigger factor (idiopathic frozen shoulder). Rheumatic disease progression and recent shoulder surgery can also cause a pattern of pain and limitation similar to frozen shoulder. Intermittent periods of use may cause inflammation.

In frozen shoulder, there is a lack of synovial fluid, which normally helps the shoulder joint, a ball and socket joint, move by lubricating the gap between the humerus (upper arm bone) and the socket in the shoulder blade. The shoulder capsule thickens, swells, and tightens due to bands of scar tissue (adhesions) that have formed inside the capsule. As a result, there is less room in the joint for the humerus, making movement of the shoulder stiff and painful. This restricted space between the capsule and ball of the humerus distinguishes adhesive capsulitis from a less complicated, painful, stiff shoulder.[4]

Diagnosis

One sign of a frozen shoulder is that the joint becomes so tight and stiff that it is nearly impossible to carry out simple movements, such as raising the arm. The movement that is most severely inhibited is external rotation of the shoulder.

People often complain that the stiffness and pain worsen at night. Pain due to frozen shoulder is usually dull or aching. It can be worsened with attempted motion, or if bumped. A physical therapist, osteopath or chiropractor, physician, athletic trainer, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner may suspect the patient has a frozen shoulder if a physical examination reveals limited shoulder movement. Frozen shoulder can be diagnosed if limits to the active range of motion (range of motion from active use of muscles) are the same or almost the same as the limits to the passive range of motion (range of motion from a person manipulating the arm and shoulder). An arthrogram or an MRI scan may confirm the diagnosis, though in practice this is rarely required.

The normal course of a frozen shoulder has been described as having three stages:[5](Note: According to a clinical practice guideline for sports physical therapy there are four stages.)[1] The first stage preceding the stage one listed below. This preceding stage can be present up to 3 months and during this stage patients describe sharp pain at end ranges of motion, achy pain at rest, and sleep disturbances. Early loss of external rotation with an intact rotator cuff is a hallmark sign in this stage.[1]

- Stage one: The "freezing" or painful stage, which may last from six weeks to nine months, and in which the patient has a slow onset of pain. As the pain worsens, the shoulder loses motion.[6]

- Stage two: The "frozen" or adhesive stage is marked by a slow improvement in pain but the stiffness remains. This stage generally lasts from four to nine months.

- Stage three: The "thawing" or recovery, when shoulder motion slowly returns toward normal. This generally lasts from 5 to 26 months.[7]

MRI and ultrasound

Imaging features of adhesive capsulitis are seen on non-contrast MRI, though MR arthrography and invasive arthroscopy are more accurate in diagnosis.[8] Ultrasound and MRI can help in diagnosis by assessing the coracohumeral ligament, with a width of greater than 3 mm being 60% sensitive and 95% specific for the diagnosis. The condition can also be associated with edema or fluid at the rotator interval, a space in the shoulder joint normally containing fat between the supraspinatus and subscapularis tendons, medial to the rotator cuff. Shoulders with adhesive capsulitis also characteristically fibrose and thicken at the axillary pouch and rotator interval, best seen as dark signal on T1 sequences with edema and inflammation on T2 sequences.[9] A finding on ultrasound associated with adhesive capsulitis is hypoechoic material surrounding the long head of the biceps tendon at the rotator interval, reflecting fibrosis. In the painful stage, such hypoechoic material may demonstrate increased vascularity with Doppler ultrasound.[10]

Prevention

To prevent the problem, a common recommendation is to keep the shoulder joint fully moving to prevent a frozen shoulder. Often a shoulder will hurt when it begins to freeze. Because pain discourages movement, further development of adhesions that restrict movement will occur unless the joint continues to move full range in all directions (adduction, abduction, flexion, rotation, and extension). Physical therapy and occupational therapy can help with continued movement.

However, a 2004 study showed that "supervised neglect" (which is supportive therapy and exercises within pain limits) [11] has a higher rate of recovery versus intense physical therapy and passive stretching.[11] The above paragraph shouldn't be taken as advice to ignore - limiting your motions to avoid the pain caused by shoulder motions is exactly why serious cases of this problem can develop.

Management

Management of this disorder focuses on restoring joint movement and reducing shoulder pain, involving medications, physical therapy, and/or surgical intervention. Treatment may continue for months; there is no strong evidence to favor any particular approach.[12]

Medications frequently used include NSAIDs; corticosteroids are used in some cases either through local injection or systemically. Oral steroids may provide short-lived benefits in range of movement and pain.[13] However, if a person has Diabetes Mellitus, then using corticosteroids can do more harm than good. Steroid injections could influence the blood sugar level, and current evidence suggested that physical therapy could be a better alternative.[14] The benefits of steroid injections may also be short-lived.[15] It is unclear whether ultrasound guided injections can improve pain or function over intramuscular injections.[16] Manual therapists like osteopaths, chiropractors and physical therapists (physiotherapists) may include massage therapy and daily extensive stretching.[12]

Physical Therapy(PT) treatment

PT treatment is utilized as an initial treatment in adhesive capsulitis or frozen shoulder with the use of different Range of motion(ROM) exercises and manual therapy techniques of shoulder joint to restore range and function. Good results have been reported with PT treatment alone or in combination with various other conservative treatments. Initial conservative management might be successful in up to 90% cases. In case of stubborn, non-responsive adhesive capsulitis, it may achieve improved results after surgical procedure and postoperative rehabilitation although there are many other important factors which decide if a person is a candidate for surgery or not. [17]

Physical therapists may utilize joint mobilizations directly at the glenohumeral joint to decrease pain, increase function, and increase range of motion as another form of treatment.[1] Additional interventions include modalities such as ultrasound, shortwave diathermy, laser therapy and electrical stimulation.[1][18] Another osteopathic technique used to treat the shoulder is called the Spencer technique.

If these measures are unsuccessful, manipulation of the shoulder under general anesthesia to break up the adhesions is sometimes used.[12] Hydrodilatation or distension arthrography is controversial.[19] However, few studies show that arthrographic distension may play a positive role in reducing pain and, therefore, improve range of movement and function.[20] Surgery to cut the adhesions (capsular release) may be indicated in prolonged and severe cases; the procedure is usually performed by arthroscopy.[21] Surgical evaluation of other problems with the shoulder, e.g., subacromial bursitis or rotator cuff tear may be needed.

Resistant adhesive capsulitis may respond to open release surgery. This technique allows the surgeon to find and correct the underlying cause of restricted glenohumeral movement such as contracture of coracohumeral ligament and rotator interval.[22]

A study published in 2004 by Diercks and Stevens showed that supervised neglect had a better outcome than intense physical therapy. "Supervised neglect" meant home exercises (pendulum exercises and active exercises within the painless range) and resumption of all activities that were tolerated. "Intense physical therapy" meant passive stretching and manual mobilization together with exercises beyond the pain threshold. Both groups received anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDs) or analgesics as necessary; neither group received corticosteroid medication or any treatment under anesthesia. The proportion of patients achieving normal or near-normal painless shoulder function at 24 months was 89% in the supervised neglect group, vs 63% in the intense physical therapy group.[11]

A more recent 2016 review had evaluated the efficacy and safety of steroid injections compared to physical therapy. The present results showed that both interventions had similar effect in improving shoulder function and decreasing pain.[14] Although, other studies have reported to find a combination of manual therapy and exercise as less effective than glucocorticoid injections.[23]

Epidemiology

The incidence of adhesive capsulitis is approximately 3 percent in the general population, but some researchers cast doubt on this often cited figure because of how often the disease is misdiagnosed; this would make the disease much rarer than previously thought.[24] Occurrence is rare in children and people under 40 but peaks between 40 and 70 years of age.[12] At least in its idiopathic form, the condition is much more common in women than in men (70% of patients are women aged 40–60). Frozen shoulder is more frequent in diabetic patients and is more severe and more protracted than in the non-diabetic population.[25]

People with diabetes, stroke, lung disease, rheumatoid arthritis, or heart disease are at a higher risk for frozen shoulder. Injury or surgery to the shoulder or arm may cause blood flow damage or the capsule to tighten from reduced use during recovery.[4] Adhesive capsulitis has been indicated as a possible adverse effect of some forms of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Cases have also been reported after breast and lung surgery.[26]

References

- Kelley MJ, Shaffer MA, Kuhn JE, Michener LA, Seitz AL, Uhl TL, et al. (May 2013). "Shoulder pain and mobility deficits: adhesive capsulitis". The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 43 (5): A1–31. doi:10.2519/jospt.2013.0302. PMID 23636125.

- Uppal HS, Evans JP, Smith C (March 2015). "Frozen shoulder: A systematic review of therapeutic options". World Journal of Orthopedics. 6 (2): 263–8. doi:10.5312/wjo.v6.i2.263. PMC 4363808. PMID 25793166.

- Jayson MI (October 1981). "Frozen shoulder: adhesive capsulitis". British Medical Journal. 283 (6298): 1005–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.283.6298.1005. JSTOR 29503905. PMC 1495653. PMID 6794738.

- "Frozen shoulder – Causes". Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- "Your Orthopaedic Connection: Frozen Shoulder". Retrieved 2008-01-28.

- Burnham J. "Frozen Shoulder Diagnosis & Management". Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- "Reduce Frozen Shoulder Recovery Time". 2016-06-24. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- Neviaser TJ. Arthrography of the shoulder. Orthop Clin North Am 1980; 11:205-17

- Shaikh A, Sundaram M (January 2009). "Adhesive capsulitis demonstrated on magnetic resonance imaging". Orthopedics. 32 (1): 2–62. doi:10.3928/01477447-20090101-20. PMID 19226048.

- Arend CF. Ultrasound of the Shoulder. Master Medical Books, 2013. Chapter on ultrasound findings of adhesive capsulitis available at ShoulderUS.com

- Diercks RL, Stevens M (2004). "Gentle thawing of the frozen shoulder: a prospective study of supervised neglect versus intensive physical therapy in seventy-seven patients with frozen shoulder syndrome followed up for two years". Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 13 (5): 499–502. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2004.03.002. PMID 15383804.

- Ewald A (February 2011). "Adhesive capsulitis: a review". American Family Physician. 83 (4): 417–22. PMID 21322517.

- Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM, Johnston RV (October 2006). "Oral steroids for adhesive capsulitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD006189. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006189. PMID 17054278.

- Sun Y, Lu S, Zhang P, Wang Z, Chen J (May 2016). "Steroid Injection Versus Physiotherapy for Patients With Adhesive Capsulitis of the Shoulder: A PRIMSA Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". Medicine. 95 (20): e3469. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000003469. PMC 4902394. PMID 27196452.

- Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM (2003-01-20). "Corticosteroid injections for shoulder pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004016. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004016. PMC 6464922. PMID 12535501.

- Bloom JE, Rischin A, Johnston RV, Buchbinder R (August 2012). "Image-guided versus blind glucocorticoid injection for shoulder pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD009147. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009147.pub2. PMID 22895984.

- Cho CH, Bae KC, Kim DH (September 2019). "Treatment Strategy for Frozen Shoulder". Clinics in Orthopedic Surgery. 11 (3): 249–257. doi:10.4055/cios.2019.11.3.249. PMC 6695331. PMID 31475043.

- Green S, Buchbinder R, Hetrick S (2003-04-22). "Physiotherapy interventions for shoulder pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD004258. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004258. PMID 12804509.

- Tveitå EK, Tariq R, Sesseng S, Juel NG, Bautz-Holter E (April 2008). "Hydrodilatation, corticosteroids and adhesive capsulitis: a randomized controlled trial". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 9: 53. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-9-53. PMC 2374785. PMID 18423042.

- Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM, Johnston RV, Cumpston M (January 2008). "Arthrographic distension for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD007005. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007005. PMID 18254123.

- Baums MH, Spahn G, Nozaki M, Steckel H, Schultz W, Klinger HM (May 2007). "Functional outcome and general health status in patients after arthroscopic release in adhesive capsulitis". Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 15 (5): 638–44. doi:10.1007/s00167-006-0203-x. PMID 17031613.

- D'Orsi GM, Via AG, Frizziero A, Oliva F (April 2012). "Treatment of adhesive capsulitis: a review". Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. 2 (2): 70–8. PMC 3666515. PMID 23738277.

- Page MJ, Green S, Kramer S, Johnston RV, McBain B, Chau M, Buchbinder R (August 2014). "Manual therapy and exercise for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD011275. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011275. PMID 25157702.

- Bunker T (2009). "Time for a new name for frozen shoulder—contracture of the shoulder". Shoulder&Elbow. 1: 4–9. doi:10.1111/j.1758-5740.2009.00007.x.

- "Questions and Answers about Shoulder Problems". Retrieved 2008-01-28.

- Adam R (10 May 2016). "Frozen Shoulder – What, Where, Why and How To Get Relief". Spine Scan. Spine Scan. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

This article contains text from the public domain document "Frozen Shoulder", American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

Further reading

- Siegel LB, Cohen NJ, Gall EP (April 1999). "Adhesive capsulitis: a sticky issue". American Family Physician. 59 (7): 1843–52. PMID 10208704.

- Radiology image sequence demonstrating CT guided shoulder hydrodilatation

- "Adhesive Capsulitis" from Arend CF. Ultrasound of the Shoulder. Master Medical Books, 2013.

- A "Neuromanual" treatment for frozen shoulder using local anesthetic from the Russian Journal of Manual Therapy, 2012

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |