Frontostriatal circuit

Frontostriatal circuits are neural pathways that connect frontal lobe regions with the basal ganglia (striatum) that mediate motor, cognitive, and behavioural functions within the brain.[1] They receive inputs from dopaminergic, serotonergic, noradrenergic, and cholinergic cell groups that modulate information processing.[2] Frontostriatal circuits are part of the executive functions. Executive functions includes following: selection and perception of important information, manipulation of information in working memory, planning and organization, behavioral control, adaptation to changes, and decision making.[3] These circuits are involved in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease as well as neuropsychiatric disorders including schizophrenia, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).[3][4][5]

Anatomy

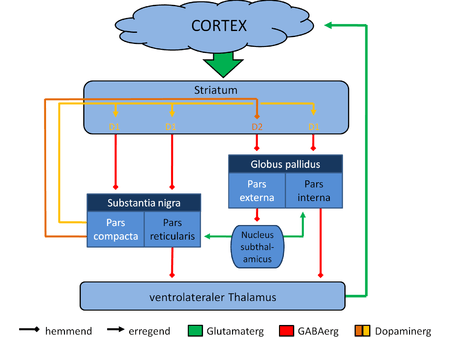

There are five defined frontostriatal circuits: motor and oculomotor circuits originating in the frontal eye fields are involved in motor functions; while dorsolateral prefrontal, orbital frontal, and anterior cingulate circuits are involved in executive functions, social behavior and motivational states.[2] These five circuits share same anatomical structures. These circuits originate in prefrontal cortex and project to the striatum followed by globus pallidus and substantia nigra and finally to the thalamus.[2] There are also feedback loops from thalamus back to prefrontal cortex completing the closed loop circuits. Also, there are open connections to these circuits integrating information from other areas of the brain.[2]

Function

The role of frontostriatal circuits is not well understood. Two of the common theories are action selection and reinforcement learning. The action selection hypothesis suggest that frontalcortex generates possible actions and the striatum selects one of these actions by inhibiting the execution of other actions while allowing the selected action execution.[6] Whereas, the reinforcement learning hypothesis suggest that prediction errors are used to update future reward expectations for selected actions and this guides the selection of actions based on reward expectations.[7]

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex and its connections to ventral striatum and amygdala are important in affective-emotional processing. They are responsible for elaboration of the plan of actions responsible for goal-directed behavior.[8] In the eye movement circuitry, prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex provide the cognitive control of attention and eye movements, while striatum and brainstem initiate the eye movements. Reduced recruitment of prefrontal cortex while relatively intact brainstem functions during task performance contributes to deficits in the voluntary control of saccades in individual with autism.[9]

It was found that self-esteem is related to the connectivity of frontostriatal circuits, suggesting that feelings of self-worth may emerge from neural systems which integrate information about the self with positive affect and reward.[10]

Dorsolateral prefrontal circuit

This circuit is important in executive functions including complex problem solving, learning new information, planning ahead, recalling remote memories, responding with appropriate behavior, and chronological ordering of events.[2]

Orbital frontal circuit

This circuit connects the frontal monitoring systems to the limbic system. Dysfunction of this circuit often results in personality change including behavioral disinhibition, emotional lability, aggressive outbursts, poor judgment, and lack of interpersonal sensitivity.[2][11]

Anterior cingulate circuit

This circuit mediates motivated behavior, response selection, error detection, performance and competition monitoring, working memory, and novelty detection.[12] Dysfunction in this circuits lead to decreased motivation including prominent apathy, indifference to pain, thirst or hunger, lack of spontaneous movements, and verbalization.[2]

References

- Alexander, G E; DeLong, M R; Strick, P L (1 March 1986). "Parallel Organization of Functionally Segregated Circuits Linking Basal Ganglia and Cortex". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 9 (1): 357–381. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002041. PMID 3085570.

- Tekin, Sibel; Cummings, Jeffrey L (August 2002). "Frontal–subcortical neuronal circuits and clinical neuropsychiatry". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 53 (2): 647–654. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00428-2.

- Chudasama, Y.; Robbins, T.W. (July 2006). "Functions of frontostriatal systems in cognition: Comparative neuropsychopharmacological studies in rats, monkeys and humans" (PDF). Biological Psychology. 73 (1): 19–38. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.01.005. PMID 16546312.

- Riley, Jeffrey D.; Moore, Stephanie; Cramer, Steven C.; Lin, Jack J. (May 2011). "Caudate atrophy and impaired frontostriatal connections are linked to executive dysfunction in temporal lobe epilepsy". Epilepsy & Behavior. 21 (1): 80–87. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.03.013. PMC 3090499. PMID 21507730.

- Alexopoulos (June 2005). "Depression in the elderly". The Lancet. 365 (9475): 1961–1970. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66665-2. PMID 15936426.

- Seo, Moonsang; Lee, Eunjeong; Averbeck, Bruno B. (7 June 2012). "Action Selection and Action Value in Frontal-Striatal Circuits". Neuron. 74 (5): 947–960. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.037. PMC 3372873. PMID 22681697.

- Schonberg, T.; Daw, N. D.; Joel, D.; O'Doherty, J. P. (21 November 2007). "Reinforcement Learning Signals in the Human Striatum Distinguish Learners from Nonlearners during Reward-Based Decision Making". Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (47): 12860–12867. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2496-07.2007. PMID 18032658.

- Guimarães, Henrique Cerqueira; Levy, Richard; Teixeira, Antônio Lúcio; Beato, Rogério Gomes; Caramelli, Paulo (June 2008). "Neurobiology of apathy in Alzheimer's disease". Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 66 (2b): 436–443. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2008000300035.

- Takarae, Yukari; Minshew, Nancy J.; Luna, Beatriz; Sweeney, John A. (November 2007). "Atypical involvement of frontostriatal systems during sensorimotor control in autism". Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 156 (2): 117–127. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.03.008. PMC 2180158. PMID 17913474.

- Chavez, Robert S.; Heatherton, Todd F. (April 28, 2014). "Multimodal frontostriatal connectivity underlies individual differences in self-esteem". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 10 (3): 364–370. doi:10.1093/scan/nsu063. PMC 4350482. PMID 24795440. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- Bachevalier, Jocelyne; Loveland, Katherine A. (January 2006). "The orbitofrontal–amygdala circuit and self-regulation of social–emotional behavior in autism". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 30 (1): 97–117. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.07.002. PMID 16157377.

- Bush, G.; Vogt, B. A.; Holmes, J.; Dale, A. M.; Greve, D.; Jenike, M. A.; Rosen, B. R. (26 December 2001). "Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex: A role in reward-based decision making". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (1): 523–528. doi:10.1073/pnas.012470999. PMC 117593. PMID 11756669.

External links

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11154/ Neurosciene - NCBI bookshelf

- http://www.frontiersin.org/Neural_Circuits Frontier specialty journal