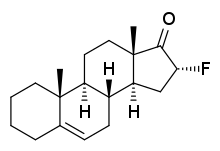

Fluasterone

Fluasterone, also known as 3β-dehydroxy-16α-fluoro-DHEA or 16α-fluoroandrost-5-en-17-one, is a fluorinated synthetic analogue of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) which was under investigation by Aeson Therapeutics for a variety of therapeutic indications including cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, obesity, and traumatic brain injury among others but was ultimately never marketed.[1][2] It is a modification of DHEA in which the C3β hydroxyl has been removed and a hydrogen atom has been substituted with a fluorine atom at the C16α position. Fluasterone reached phase II clinical trials prior to the discontinuation of its development.[3]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | 3β-Dehydroxy-16α-fluoro-DHEA; Fl-DHEA; DHEF; DHEA 8354; DHEA analogue 8354; HE-2500; 16α-Fluoroandrost-5-en-17-one |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C19H27FO |

| Molar mass | 290.422 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

The mechanism of action of DHEA and fluasterone is unknown.[4][5][6] However, similarly to DHEA but more strongly, fluasterone is a potent uncompetitive inhibitor of G6PDH (Ki = 0.5 μM versus 17 μM for DHEA).[4] The drug retains the antiinflammatory, antihyperplastic, chemopreventative, antihyperlipidemic, antidiabetic, and antiobesic, as well as certain immunomodulating activities of DHEA, much but not all of which it is thought may possibly be mediated via G6PDH inhibition (with some experimental evidence to support this notion available).[4][6][7][8]

Conversely, unlike DHEA, fluasterone has minimal or no androgenic or estrogenic activity, and due to the presence of the fluorine atom at the C16α position, its metabolism at the C17α position is sterically hindered and thus it cannot be metabolized into androgens like testosterone or estrogens like estradiol.[6][9][4] Also in contrast to DHEA, fluasterone does not produce sedation or seizures in animals and hence is not thought to interact with the GABAA receptor.[10] In addition, unlike DHEA, fluasterone has reduced or no effects as a peroxisome proliferator (i.e., lacks activity at the PPARα), and hence does not pose a risk of liver toxicities such as hepatomegaly or hepatocellular carcinoma.[4] It is for these reasons that fluasterone was developed and was considered to be advantageous to DHEA.[4][6]

Due to extensive first-pass hepatic and/or gastrointestinal metabolism, very high doses of DHEA and fluasterone are necessary for effectiveness.[4] In animals, the efficacy of fluasterone is increased 40-fold when administered parenterally, and for this reason, a non-oral formulation of fluasterone was selected for clinical development.[4] However, the development of fluasterone was nonetheless stopped reportedly due to its low potency and low oral bioavailability, which are said to have rendered it unsuitable for clinical use.[11]

References

- http://adisinsight.springer.com/drugs/800006506

- Achille G. Gravanis; Synthia H. Mellon (24 June 2011). Hormones in Neurodegeneration, Neuroprotection, and Neurogenesis. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 170–. ISBN 978-3-527-63397-5.

- Alain Tressaud; Günter Haufe (6 June 2008). Fluorine and Health: Molecular Imaging, Biomedical Materials and Pharmaceuticals. Elsevier. pp. 603–. ISBN 978-0-08-055811-0.

- Schwartz AG, Pashko LL (2004). "Dehydroepiandrosterone, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, and longevity". Ageing Res. Rev. 3 (2): 171–87. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2003.05.001. PMID 15177053.

- Schwartz AG, Pashko LL (2001). "Potential therapeutic use of dehydroepiandrosterone and structural analogs". Diabetes Technol. Ther. 3 (2): 221–4. doi:10.1089/152091501300209589. PMID 11478328.

- Ciolino HP, MacDonald CJ, Yeh GC (2002). "Inhibition of carcinogen-activating enzymes by 16alpha-fluoro-5-androsten-17-one". Cancer Res. 62 (13): 3685–90. PMID 12097275.

- McCormick DL, Johnson WD, Kozub NM, Rao KV, Lubet RA, Steele VE, Bosland MC (2007). "Chemoprevention of rat prostate carcinogenesis by dietary 16alpha-fluoro-5-androsten-17-one (fluasterone), a minimally androgenic analog of dehydroepiandrosterone". Carcinogenesis. 28 (2): 398–403. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgl141. PMID 16952912.

- Auci D, Kaler L, Subramanian S, Huang Y, Frincke J, Reading C, Offner H (2007). "A new orally bioavailable synthetic androstene inhibits collagen-induced arthritis in the mouse: androstene hormones as regulators of regulatory T cells". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1110: 630–40. doi:10.1196/annals.1423.066. PMID 17911478.

- Brown, Alan P.; Kirchner, Debra L.; Morrissey, Robert L.; Das, Saroj R.; Fitzgerald, Robert L.; Crowell, James A.; Levine, Barry S. (2003). "Endocrine effects of dehydroepiandrosterone and its fluorinated analog, fluasterone, in rats". Drug Development Research. 58 (2): 169–178. doi:10.1002/ddr.10156. ISSN 0272-4391.

- Malik AS, Narayan RK, Wendling WW, Cole RW, Pashko LL, Schwartz AG, Strauss KI (2003). "A novel dehydroepiandrosterone analog improves functional recovery in a rat traumatic brain injury model". J. Neurotrauma. 20 (5): 463–76. doi:10.1089/089771503765355531. PMC 1456324. PMID 12803978.

- Ronald Ross Watson (22 July 2011). DHEA in Human Health and Aging. CRC Press. pp. 212–. ISBN 978-1-4398-3884-6.