Extrapulmonary tuberculosis

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis is tuberculosis (TB) within a location in the body other than the lungs. This occurs in 15–20% of active cases, causing other kinds of TB.[2] These are collectively denoted as "extrapulmonary tuberculosis".[3] Extrapulmonary TB occurs more commonly in immunosuppressed persons and young children. In those with HIV, this occurs in more than 50% of cases.[3] Notable extrapulmonary infection sites include the pleura (in tuberculous pleurisy), the central nervous system (in tuberculous meningitis), the lymphatic system (in scrofula of the neck), the genitourinary system (in urogenital tuberculosis), and the bones and joints (in Pott disease of the spine), among others.

Spread to lymph nodes is the most common.[4] An ulcer originating from nearby infected lymph nodes may occur and is painless, slowly enlarging and has an appearance of "wash leather".[5]

When it spreads to the bones, it is known as "osseous tuberculosis",[6] a form of osteomyelitis.[7] Tuberculosis has been present in humans since ancient times.[8] A potentially more serious, widespread form of TB is called "disseminated tuberculosis", also known as miliary tuberculosis.[9] Miliary TB currently makes up about 10% of extrapulmonary cases.[10]

Tuberculous peritonitis

There are three forms of tuberculous peritonitis:

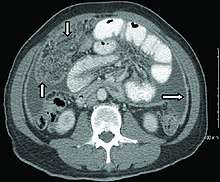

- Wet type presents with abundant and relatively increased density ascites (20-45 HU), smooth peritoneal thickening and omental smudge. Thickened strands with crowded vascular bundles in the mesentery are characteristic.[11]

- Fixed fibrotic form- With imaging appears as omental mass, matted bowel loops and nodular / irregular thickening of bowel and mesentery, and sometimes with loculated ascites. This form is considered as great mimic of peritoneal carcinomatosis.[11]

- The dry or plastic form causes a fibrous reaction in the peritoneum results in adhesion of bowel loops and caseous lymph nodes.[11]

Other findings in the abdomen such as miliary microabscesses in the liver or spleen, splenomegaly, splenic or lymph node calcification, inflammatory thickening of the terminal ileum and caecum, patulous I-C junction and low attenuation lymphadenopathy may help suggest tuberculosis as the etiology of diffuse peritoneal disease.[11]

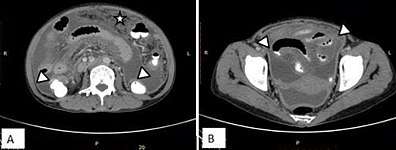

Case of “wet type” of tuberculous peritonitis. A and B. Smudge pattern of greater omental involvement (star) with smooth peritoneal thickening and enhancement. Thickened serosal surface of small and large bowel loops (arrow heads) with ascites.[11]

Case of “wet type” of tuberculous peritonitis. A and B. Smudge pattern of greater omental involvement (star) with smooth peritoneal thickening and enhancement. Thickened serosal surface of small and large bowel loops (arrow heads) with ascites.[11] A 24 year old male patient with fibrotic type of tubercular peritonitis.[11]

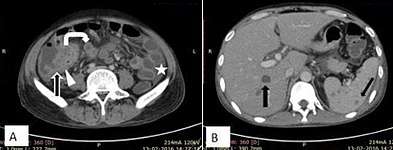

A 24 year old male patient with fibrotic type of tubercular peritonitis.[11]

A. Marked ascites with centrally displaced bowel loops, mimicking peritoneal carcinomatosis. Splenic microabscesses (curved arrow) also noted.

B. Peripherally enhancing central hypodense mesenteric lymph nodes (arrow).

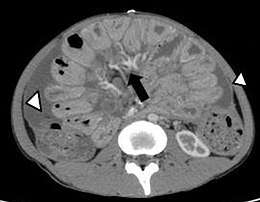

C. Smooth peritoneal thickening and enhancement.[11] A 32 year old male patient, a case of abdominal tuberculosis. A and B. Ileocecal wall thickening (straight arrow), patulous IC junction (arrow head), caseous mesenteric lymphnodes (curved arrow) with ascites (star). B. Hepatic and splenic microabscesses (arrows).[11]

A 32 year old male patient, a case of abdominal tuberculosis. A and B. Ileocecal wall thickening (straight arrow), patulous IC junction (arrow head), caseous mesenteric lymphnodes (curved arrow) with ascites (star). B. Hepatic and splenic microabscesses (arrows).[11]

Like tuberculosis, Crohn's disease can result in granulomatous peritonitis. Smooth and regular peritoneal thickening is more in favor of granulomatous peritonitis.[11]

References

- Akce, Mehmet; Bonner, Sarah; Liu, Eugene; Daniel, Rebecca (2014). "Peritoneal Tuberculosis Mimicking Peritoneal Carcinomatosis". Case Reports in Medicine. 2014: 1–3. doi:10.1155/2014/436568. ISSN 1687-9627. PMC 3970461. CC-BY 3.0

- Jindal, editor-in-chief SK (2011). Textbook of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. p. 549. ISBN 978-93-5025-073-0. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Golden MP, Vikram HR (2005). "Extrapulmonary tuberculosis: an overview". American Family Physician. 72 (9): 1761–8. PMID 16300038.

- Rockwood, RR (August 2007). "Extrapulmonary TB: what you need to know". The Nurse practitioner. 32 (8): 44–9. doi:10.1097/01.npr.0000282802.12314.dc. PMID 17667766.

- Burkitt, H. George (2007). Essential Surgery: Problems, Diagnosis & Management 4th ed. p. 34. ISBN 9780443103452.

- Kabra, [edited by] Vimlesh Seth, S.K. (2006). Essentials of tuberculosis in children (3rd ed.). New Delhi: Jaypee Bros. Medical Publishers. p. 249. ISBN 978-81-8061-709-6. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell RN (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. pp. 516–522. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- Lawn, SD; Zumla, AI (2 July 2011). "Tuberculosis". Lancet. 378 (9785): 57–72. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62173-3. PMID 21420161.

- Dolin, [edited by] Gerald L. Mandell, John E. Bennett, Raphael (2010). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases (7th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. Chapter 250. ISBN 978-0-443-06839-3.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Ghosh, editors-in-chief, Thomas M. Habermann, Amit K. (2008). Mayo Clinic internal medicine: concise textbook. Rochester, MN: Mayo Clinic Scientific Press. p. 789. ISBN 978-1-4200-6749-1. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Subhaschandra Singh, Y. Sobita Devi, Shweta Bhalothia and Veeraraghavan Gunasekaran (2016). "Peritoneal Carcinomatosis: Pictorial Review of Computed Tomography Findings". International Journal of Advanced Research. 4 (7): 735–748. doi:10.21474/IJAR01/936. ISSN 2320-5407.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CC-BY 4.0