Anatomical terms of motion

Motion, the process of movement, is described using specific anatomical terms. Motion includes movement of organs, joints, limbs, and specific sections of the body. The terminology used describes this motion according to its direction relative to the anatomical position of the joints. Anatomists use a unified set of terms to describe most of the movements, although other, more specialized terms are necessary for describing the uniqueness of the movements such as those of the hands, feet, and eyes.

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Anatomical terminology |

|---|

| Bone |

| Location |

| Microanatomy |

| Motion |

| Muscle |

| Neuroanatomy |

| Glossary of medicine |

In general, motion is classified according to the anatomical plane it occurs in. Flexion and extension are examples of angular motions, in which two axes of a joint are brought closer together or moved further apart. Rotational motion may occur at other joints, for example the shoulder, and are described as internal or external. Other terms, such as elevation and depression, describe movement above or below the horizontal plane. Many anatomical terms derive from Latin terms with the same meaning.

Classification

Motions are classified after the anatomical planes they occur in,[1] although movement is more often than not a combination of different motions occurring simultaneously in several planes.[2] Motions can be split into categories relating to the nature of the joints involved:

- Gliding motions occur between flat surfaces, such as in the intervertebral discs or between the carpal and metacarpal bones of the hand.[1]

- Angular motions occur over synovial joints and causes them to either increase or decrease angles between bones.[1]

- Rotational motions move a structure in a rotational motion along a longitudinal axis, such as turning the head to look to either side.[3]

Apart from this motions can also be divided into:

- Linear motions (or translatory motions), which move in a line between two points. Rectilinear motion is motion in a straight line between two points, whereas curvilinear motion is motion following a curved path.[2]

- Angular motions (or rotary motions) occur when an object is around another object increasing or decreasing the angle. The different parts of the object do not move the same distance. Examples include a movement of the knee, where the lower leg changes angle compared to the femur, or movements of the ankle.[2]

The study of movement is known as kinesiology.[4] A categoric list of movements of the human body and the muscles involved can be found at list of movements of the human body.

Abnormal motion

The prefix hyper- is sometimes added to describe movement beyond the normal limits, such as in hypermobility, hyperflexion or hyperextension. The range of motion describes the total range of motion that a joint is able to do. [5] For example, if a part of the body such as a joint is overstretched or "bent backwards" because of exaggerated extension motion, then it can be described as hyperextended. Hyperextension increases the stress on the ligaments of a joint, and is not always because of a voluntary movement. It may be a result of accidents, falls, or other causes of trauma. It may also be used in surgery, such as in temporarily dislocating joints for surgical procedures. [6] Or it may be used as a pain compliance method to force a person to take a certain action, such as allowing a police officer to take him into custody.

General motion

These are general terms that can be used to describe most movements the body makes. Most terms have a clear opposite, and so are treated in pairs.[7]

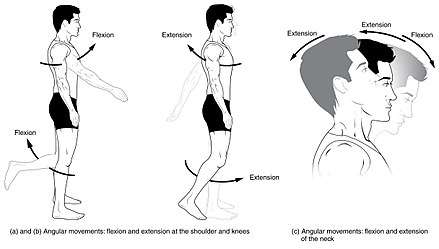

Flexion and extension

Flexion and extension describe movements that affect the angle between two parts of the body. These terms come from the Latin words with the same meaning.[lower-alpha 1]

Flexion describes a bending movement that decreases the angle between a segment and its proximal segment.[9] For example, bending the elbow, or clenching a hand into a fist, are examples of flexion. When sitting down, the knees are flexed. When a joint can move forward and backward, such as the neck and trunk, flexion is movement in the anterior direction.[10] When the chin is against the chest, the head is flexed, and the trunk is flexed when a person leans forward.[10] Flexion of the shoulder or hip is movement of the arm or leg forward.[11]

Extension is the opposite of flexion, describing a straightening movement that increases the angle between body parts.[12] For example, when standing up, the knees are extended. When a joint can move forward and backward, such as the neck and trunk, extension is movement in the posterior direction.[10] Extension of the hip or shoulder moves the arm or leg backward.[11]

Abduction and adduction

.jpg)

Abduction is the motion of a structure away from the midline while adduction refer to motion towards the center of the body.[13] The centre of the body is defined as the midsagittal plane.[3] These terms come from Latin words with similar meanings, ab- being the Latin prefix indicating "away," ad- indicating "toward," and ducere meaning "to draw or pull" (cf. English words "duct," "conduct," "induction").[lower-alpha 2]

Abduction is a motion that pulls a structure or part away from the midline of the body. In the case of fingers and toes, it is spreading the digits apart, away from the centerline of the hand or foot. Abduction of the wrist is also called radial deviation.[13] For example, raising the arms up, such as when tightrope-walking, is an example of abduction at the shoulder.[11] When the legs are splayed at the hip, such as when doing a star jump or doing a split, the legs are abducted at the hip.[3]

Adduction is a motion that pulls a structure or part toward the midline of the body, or towards the midline of a limb. In the case of fingers and toes, it is bringing the digits together, towards the centerline of the hand or foot. Adduction of the wrist is also called ulnar deviation. Dropping the arms to the sides, and bringing the knees together, are examples of adduction.[13]

Ulnar deviation is the hand moving towards the ulnar styloid (or, towards the pinky/fifth digit). Radial deviation is the hand moving towards the radial styloid (or, towards the thumb/first digit).[15]

Elevation and depression

The terms elevation and depression refer to movement above and below the horizontal. They derive from the Latin terms with similar meanings[lower-alpha 3]

Elevation is movement in a superior direction.[17] For example, shrugging is an example of elevation of the scapula. [18]

Depression is movement in an inferior direction, the opposite of elevation.[19]

Rotation

.jpg)

Rotation of body parts is referred to as internal or external, referring to rotation towards or away from the center of the body.[20]

Internal rotation (or medial rotation) is rotation towards the axis of the body.[20]

External rotation (or lateral rotation) is rotation away from the center of the body.[20]

The lotus position of yoga, demonstrating external rotation of the leg at the hip.

The lotus position of yoga, demonstrating external rotation of the leg at the hip. Rotating the arm away from the body is external rotation.

Rotating the arm away from the body is external rotation. Rotating the arm closer to the body is internal rotation.

Rotating the arm closer to the body is internal rotation.

Other

- Anterograde and retrograde flow refer to movement of blood or other fluids in a normal (anterograde) or abnormal (retrograde) direction.[21]

- Circumduction is a conical movement of a body part, such as a ball and socket joint or the eye. Circumduction is a combination of flexion, extension, adduction and abduction. Circumduction can be best performed at ball and socket joints, such as the hip and shoulder, but may also be performed by other parts of the body such as fingers, hands, feet, and head.[22] For example, circumduction occurs when spinning the arm when performing a serve in tennis or bowling a cricket ball. [23]

- Reduction is a motion returning a bone to its original state,[24] such as a shoulder reduction following shoulder dislocation, or reduction of a hernia.

The swinging action made during a tennis serve is an example of circumduction

The swinging action made during a tennis serve is an example of circumduction

Special motion

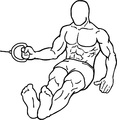

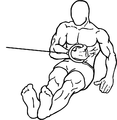

Hands and feet

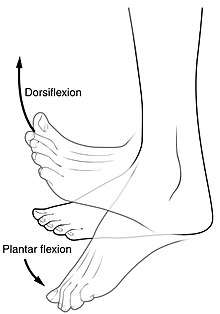

Flexion and extension of the foot

Dorsiflexion and plantar flexion refer to extension or flexion of the foot at the ankle. These terms refer to flexion in direction of the "back" of the foot, dorsum pedi, which is the upper surface of the foot when standing, and flexion in direction of the sole of the foot, plantar pedi. These terms are used to resolve confusion, as technically extension of the joint is dorsiflexion, which could be considered counter-intuitive as the motion reduces the angle between the foot and the leg.[25]

Dorsiflexion is where the toes are brought closer to the shin. This decreases the angle between the dorsum of the foot and the leg.[26] For example, when walking on the heels the ankle is described as being in dorsiflexion.[25]

Plantar flexion or plantarflexion is the movement which decreases the angle between the sole of the foot and the back of the leg; for example, the movement when depressing a car pedal or standing on tiptoes.[25]

A ballerina, demonstrating plantar flexion of the feet

A ballerina, demonstrating plantar flexion of the feet Dorsi and plantar flexion of the foot

Dorsi and plantar flexion of the foot

Flexion and extension of the hand

Palmarflexion and dorsiflexion refer to movement of the flexion (palmarflexion) or extension (dorsiflexion) of the hand at the wrist.[27] These terms refer to flexion between the hand and the body's dorsal surface, which in anatomical position is considered the back of the arm; and flexion between the hand and the body's palmar surface, which in anatomical position is considered the anterior side of the arm.[28] The direction of terms are opposite to those in the foot because of embryological rotation of the limbs in opposite directions.[10]

Palmarflexion is decreasing the angle between the palm and the anterior forearm.[27]

Dorsiflexion is extension at the ankle or wrist joint. This brings the hand closer to the dorsum of the body.[27]

Praying Hands by Albrecht Dürer, demonstrating dorsiflexion of the hands.

Praying Hands by Albrecht Dürer, demonstrating dorsiflexion of the hands.

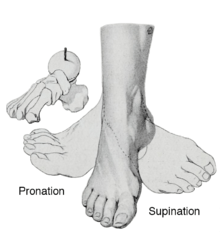

Pronation and supination

Pronation (/proʊˈneɪʃən/) and supination (/suːpɪˈneɪʃən/) refer most generally to assuming prone or supine positions, but often they are used in a specific sense referring to rotation of the forearm or foot so that in the standard anatomical position the palm or sole is facing anteriorly (supination) or posteriorly (pronation).[29]

Pronation at the forearm is a rotational movement where the hand and upper arm are turned inwards. Pronation of the foot is turning of the sole outwards, so that weight is borne on the medial part of the foot.[30]

Supination of the forearm occurs when the forearm or palm are rotated outwards. Supination of the foot is turning of the sole of the foot inwards, shifting weight to the lateral edge.[31]

Supination and pronation of the foot

Supination and pronation of the foot Supination and pronation of the arm

Supination and pronation of the arm

Inversion and eversion

Inversion and eversion refer to movements that tilt the sole of the foot away from (eversion) or towards (inversion) the midline of the body.[32]

Eversion is the movement of the sole of the foot away from the median plane.[33] Inversion is the movement of the sole towards the median plane. For example, inversion describes the motion when an ankle is twisted.[26]

Example showing inversion and eversion of the foot

Example showing inversion and eversion of the foot Eversion of the right foot

Eversion of the right foot Inversion of the right foot

Inversion of the right foot

Eyes

Unique terminology is also used to describe the eye. For example:

Jaw and teeth

- Occlusion is motion of the mandibula towards the maxilla making contact between the teeth.[36]

- Protrusion and retrusion are sometimes used to describe the anterior (protrusion) and posterior (retrusion) movement of the jaw.[37]

Examples showing protrusion and retrusion.

Examples showing protrusion and retrusion. Elevation and depression of the jaw.

Elevation and depression of the jaw.

Other

Other terms include:

- Nutation and counternutation[lower-alpha 4] refer to movement of the sacrum defined by the rotation of the promontory downwards and anteriorly, as with lumbar extension (nutation); or upwards and posteriorly, as with lumbar flexion (counternutation).[39]

- Opposition is the movement that involves grasping of the thumb and fingers.[40]

- Protraction and Retraction refer to an anterior (protraction) or posterior (retraction) movement,[41] such as of the arm at the shoulders, although these terms have been criticised as non-specific.[42]

- Reciprocal motion is alternating motions in opposing directions.[43]

- Reposition is restoring an object to its natural condition.[44]

Nutation at left, counternutation at right

Nutation at left, counternutation at right An example of opposition

An example of opposition Example of opposition of the thumb and index finger

Example of opposition of the thumb and index finger

See also

Notes

References

- Marieb 2010, p. 212.

- Lippert 2011, pp. 6-7.

- Kendall 2005, p. 57.

- Lippert 2011, pp. 1-7.

- Kendall 2005, p. G-4.

- Seeley 1998, p. 229.

- "Anatomy & Physiology". Openstax college at Connexions. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- OED 1989, "flexion", "extension".

- OED 1989, "flexion".

- Kendall 2005, p. 56.

- Cook 2012, pp. 180-193.

- OED 1989, "extension".

- Swartz 2010, pp. 590–591.

- OED 1989, "adduction", "abduction", "abduct".

- See: for appropriate image

- OED 1989.

- OED 1989, "elevation".

- Kendall 2005, p. 303.

- OED 1989, "depression".

- Swartz 2010, pp. 590-1.

- OED 1989, "anterograde", "retrograde".

- Saladin 2010, p. 300.

- Kendall 2005, p. 304.

- Taber 2001, "reduction".

- Kendall 2005, p. 371.

- Kyung 2005, p. 123.

- Swartz 2010, pp. 591-593.

- OED 1989, "palmarflexion", "dorsiflexion".

- Swartz 2010, pp. 591–592.

- OED 1989, "pronation".

- OED 1989, "supination".

- Swartz 2010, p. 591.

- Kyung 2005, p. 108.

- DMD 2012, "version".

- Taber 2001, "torsion".

- Taber 2001, "occlusion".

- Taber 2001, "protrusion", "retrusion".

- OED 1989, "nutation".

- Houglum 2012, p. 333.

- Taber 2001, "opposition".

- OED 1989, "protraction", "retraction".

- Kendall 2005, p. 302.

- Taber 2001, "reciprocation".

- OED 1989, "resposition".

Sources

- Albert, Daniel (2012). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 978-1416062578.

- Chung, Kyung Won (2005). Gross Anatomy (Board Review). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-5309-0.

- Cook, Chad E. (2012). Orthopedic Manual Therapy: An Evidence Based Approach (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-13-802173-3.

- Houglum, Peggy A.; Bertoli, Dolores B. (2012). Brunnstrom's Clinical Kinesiology. F. A. Davis Company. ISBN 978-0-8036-2352-1.

- Kendall, Florence Peterson; [et al.]; et al. (2005). Muscles : testing and function with posture and pain (5th ed.). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-4780-5.

- Lippert, Lynn S. (2011). Clinical Kinesiology and Anatomy (5th ed.). F. A. Davis Company. ISBN 978-0-8036-2363-7.

- Marieb, Elaine N.; Wilhelm, Patricia B.; Mallat, Jon (2010). Human Anatomy. Pearson. ISBN 978-0-321-61611-1.

- Saladin, Kenneth S. (2010). Anatomy & Physiology The Unity of Form and Function (5th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0077361358.

- Seeley, Rod R.; Stephens, Trent D.; Tate, Philip (1998). Anatomy & Physiology (4th ed.). WCB/McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-697-41107-9.

- Simpson, John A.; Weiner, Edmung (1989). The Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198611868.

- Swartz, Mark H. (2010). Textbook of Physical Diagnosis: History and Examination (6th ed.). Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-6203-5.

- Venes, Donald (Editor); Thomas, Clayton L. (Editor); Egan, Elizabeth J. (Managing Editor); Morelli, Nancee A. (Assistant Editor); Nell, Alison D. (Assistant Editor); Matkowski, Joy (2001). Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary (illustrated in full color 19th ed.). Philadelphia: F.A.Davis Co. ISBN 0-8036-0655-9.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anatomical terms of motion. |