External cephalic version

External cephalic version (ECV) is a process by which a breech baby can sometimes be turned from buttocks or foot first to head first. It is a manual procedure that is recommended by national guidelines for breech presentation of a pregnancy with a single baby, in order to enable vaginal delivery.[2] It is usually performed late in pregnancy, that is, after 36 gestational weeks,[3] but preferably 37 weeks,[4] and can even be performed in early labour.[3]

| External cephalic version | |

|---|---|

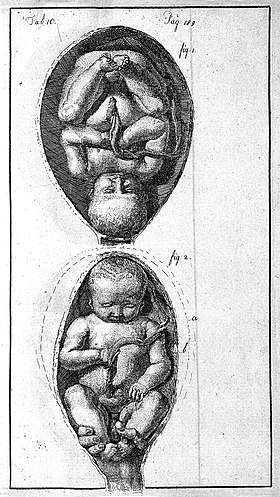

Child presenting head first (top) and feet first (bottom)[1] | |

| Specialty | Obstetrics |

| ICD-9-CM | 73.91 |

ECV is endorsed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) as a mode to avoid the risks associated with a vaginal breech or cesarean delivery for singleton breech presentation.[2][5]

ECV can be contrasted with "internal cephalic version", which involves a hand inserted through the cervix.[6]

Medical use

ECV is one option of intervention should a breech position of a baby be found after 36 weeks gestation. Other options include a planned caesarian section or planned vaginal delivery.[3]

Success rates

ECV has a success rate between 60 and 75%.[4] Various factors can alter the success rates of ECV. Practitioner experience, maternal weight, obstetric factors such as uterine relaxation, a palpable fetal head, a non-engaged breech, non-anterior placenta, and an amniotic fluid index above 7–10 cm, are all factors which can be associated with higher success rates. In addition, the effect of neuraxial blockade on ECV success rates have been conflicting, although ECV appears easier to perform under epidural block.[2][7]

Reports from a study carried out by the University Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre, between 1 September 2008 and 30 September 2010, indicate that patients in the ECV group with pregnancies which went post dates (beyond 40 weeks), two-thirds had successful vaginal delivery while a third required caesarean section.[8] Within this study the success rate of ECV was 51.4% (73/142 cases) over the three-year period.[8]

Following successful ECV, with the baby turned to head first, there is a less than 5% chance of the baby turning spontaneously to breech again.[9]

Contra-indications

Some situations exist where ECV is not indicated or may cause harm. These include recent antepartum haemorrhage, placenta praevia, abnormal fetal monitoring, ruptured membranes, multiple pregnancy, pre-eclampsia, reduced amniotic fluid and some other abnormalities of the uterus or baby.[9]

Risks

As with any procedure there can be complications most of which can be greatly decreased by having an experienced professional on the birth team. An ultrasound to estimate a sufficient amount of amniotic fluid and monitoring of the fetus immediately after the procedure can also help minimize risks.[10]

Evidence of complications of ECV from clinical trials is limited, but ECV does reduce the chance of breech presentation at birth and caesarian section. The 2015 Cochrane review concluded that "large observational studies suggest that complications are rare".[9][11]

Typical risks include umbilical cord entanglement, abruption of placenta, preterm labor, premature rupture of the membranes (PROM) and severe maternal discomfort. Overall complication rates have ranged from about 1 to 2 percent since 1979. While somewhat out of favour between 1970 and 1980, the procedure has seen an increase in use due to its relative safety.[12]

Successful ECV significantly decreases the rate of cesarean section, however, women are still at an increased risk of instrumental delivery (ventouse and forceps delivery) and cesarean section compared to women with spontaneous cephalic presentation (head first).[3][13]

Technique

The procedure is undertaken by either one or two physicians and where emergency facilities to undertake instrumental delivery and caesarian section are at hand. Blood is also taken for cross-matching should a complication arise.[12] Prior to performing ECV, an ultrasound of the abdomen is performed to confirm the breech position and the mother's blood pressure and pulse are taken. A Cardiotocography (CTG) is also performed to monitor the baby's heart.[3][14]

The procedure usually lasts a few minutes and is monitored intermittently with CTG.[5] With a covering of ultrasonic gel on the abdomen to reduce friction,[12] the physician's hands are placed on the mother's abdomen around the baby. Then, by applying firm pressure to manoeuvre the baby up and away from the pelvis and to gently turn in several steps from breech, to a sideways position, the final manipulation results in a head first presentation.[3][15] The procedure is discontinued if maternal distress, repeated failure or fetal compromise on monitoring occurs.[12]

ECV performed before term may decrease the rate of breech presentation compared to ECV at term, but may increase the risk of preterm delivery.[16] There is some evidence to support the use of tocolytic drugs in ECV.[17] Given by injection, tocolytics relax the uterus muscle and may improve the chance of turning the baby successfully. This is considered safe for the mother and baby, but can cause the mother to experience facial flushing and a feeling of a fast heart rate.[3] Use of intravenous nitroglycerin has been proposed.[18]

Following the procedure, a repeat CTG is performed and a repeat ultrasound will confirm a successful turn.[3] Should this first attempt fail, a second attempt on another day can be considered.[9]

In addition, to prevent Rh disease after the procedure, all rhesus D negative pregnant women are offered an intramuscular injection of anti-Rh antibodies (Rho(D) immune globulin).[3]

History

ECV has existed since 384-322 B.C, the time of Aristotle.[12] Around 100 A.D, Soranus of Ephesus included guidance on ECV as a way to reduce complications of vaginal breech birth. 17th century French obstetrician, François Mauriceau, is alleged to have described ECV as "a little more difficult than turning an omelette in a frying pan".[19] Justus Heinrich Wigand published an account of ECV in 1807 and the procedure was increasingly accepted following Adolphe Pinard's demonstration of it in France. In 1901, British obstetrician, Herbert R. Spencer, advocated ECV in his publication on breech birth. In 1927, obstetrician George Frederick Gibberd, reviewed 9,000 consecutive births around Guy's Hospital, London. Following his study, he recommended ECV, even if it failed and needed to be repeated and even it required anaesthesia.[19]

ECV's safety has continued to be a longstanding controversy. Following a protocol developed in Berlin, ECV did increase in popularity in the United States in the 1980s.[12] The procedure has been increasingly considered as low risk of complications and its improvement in safety as a result of the routine use of electronic fetal monitoring, waiting until closer to term and the replacement of anaesthesia by tocolysis,[19] has seen a recent resurgence.[5]

References

- Burton, John (1751). "An essay towards a complete new system of midwifry, theoretical and practical. Together with the descriptions,causes and methods of removing, or relieving the disorderspeculiar to pregnant ... women, and new-born infants". J. Hodges. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- Sharoni, L (March 2015). "Anesthesia and external cephalic version". Current Anesthesiology Reports. 5: 91–99. doi:10.1007/s40140-014-0095-0.

- "Breech baby at the end of pregnancy" (PDF). www.rcog.org. July 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- Arnold, Kate C.; Flint, Caroline J. (2017). Obstetrics Essentials: A Question-Based Review. Oklahoma, USA: Springer. pp. 231–235. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-57675-6. ISBN 978-3-319-57674-9.

- "External Cephalic Version: Overview, Technique, Periprocedural Care". Medscape. 6 August 2018.

- NEELY MR (May 1959). "Combined internal cephalic version". Ulster Med J. 28 (1): 30–4. PMC 2384304. PMID 13669146.

- Wight, William (2008). "18. External cephalic version". In Halpern, Stephen H.; Douglas, M. Joanne (eds.). Evidence-Based Obstetric Anesthesia. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 217–224. ISBN 9780727917348.

- Lim, Pei Shan, P, A (2014). "Successful External Cephalic Version: Factors Predicting Vaginal Birth". The Scientific World Journal. 2014: 860107. doi:10.1155/2014/860107. PMC 3919060. PMID 24587759.

- "External Cephalic Version and Reducing the Incidence of Breech Presentation" (PDF). www.rcog.org.uk. 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- Kok, M.; Cnossen, J.; Gravendeel, L.; Van Der Post, J. A.; Mol, B. W. (January 2009). "Ultrasound factors to predict the outcome of external cephalic version: a meta-analysis". Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 33 (1): 76–84. doi:10.1002/uog.6277. ISSN 0960-7692. PMID 19115237.

- Hofmeyr, GJ; Kulier, R; West, HM (2015). "External cephalic version for breech presentation at term (Review)" (PDF). Cochrane.

- Coco, Andrew S.; Silverman, Stephanie D. (1998-09-01). "External Cephalic Version". American Family Physician. 58 (3). ISSN 0002-838X.

- de Hundt, M; Velzel, J; de Groot, CJ; Mol, BW; Kok, M (June 2014). "Mode of delivery after successful external cephalic version: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 123 (6): 1327–34. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000000295. PMID 24807332.

- "What Is External Cephalic Version?". WebMD. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "37 weeks pregnant". www.nct.org.uk. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- Hutton, EK; Hofmeyr, GJ; Dowswell, T (29 July 2015). "External cephalic version for breech presentation before term". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7 (7): CD000084. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000084.pub3. PMID 26222245.

- Cluver, C; Gyte, GM; Sinclair, M; Dowswell, T; Hofmeyr, GJ (9 February 2015). "Interventions for helping to turn term breech babies to head first presentation when using external cephalic version". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (2): CD000184. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000184.pub4. hdl:10019.1/104301. PMID 25674710.

- Hilton J, Allan B, Swaby C, et al. (September 2009). "Intravenous nitroglycerin for external cephalic version: a randomized controlled trial". Obstet Gynecol. 114 (3): 560–7. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b05a19. PMID 19701035.(subscription required)

- Paul, Carolyn (22 March 2017). "The baby is for turning: external cephalic version". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 124 (5): 773. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14238. ISSN 1470-0328. PMID 28328063.