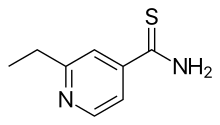

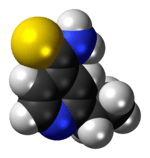

Ethionamide

Ethionamide is an antibiotic used to treat tuberculosis.[2] Specifically it is used, along with other antituberculosis medications, to treat active multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.[2] It is no longer recommended for leprosy.[3][2] It is taken by mouth.[2]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Trecator, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682402 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | by mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | ~30% |

| Elimination half-life | 2 to 3 hours |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.846 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C8H10N2S |

| Molar mass | 166.244 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 164 to 166 °C (327 to 331 °F) (dec.) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Ethionamide has a high rate of side effects.[4] Common side effects include nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and loss of appetite. Serious side effects may include liver inflammation and depression.[2] It should not be used in people with significant liver problems. Use in pregnancy is not recommended as safety is unclear.[2] Ethionamide is in the thioamides family of medications. It is believed to work by interfering with the use of mycolic acid.[5]

Ethionamide was discovered in 1956 and approved for medical use in the United States in 1965.[5][2] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[6] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about $5.94 to $24.12 USD per month.[7]

Medical uses

Ethionamide is used in combination with other antituberculosis agents as part of a second-line regimen for active tuberculosis.[8]

Ethionamide is well absorbed orally with or without food, but is often administered with food to improve tolerance.[9][10] It crosses the blood brain barrier to achieve concentrations in the cerebral-spinal fluid equivalent to plasma.[10]

The antimicrobial spectrum of ethionamide includes M. tuberculosis, M. bovis and M. segmatis.[11] It also is used rarely against infections with M. leprae[12] and other nontuberculous mycobacteria such as M. avium[13] and M. kansasii.[8] While working in a similar manner to isoniazid, cross resistance is only seen in 13% of strains, since they are both prodrugs but activated by different pathways.[14] Resistance can emerge from mutations in ethA, which is needed to activate the drug, or ethR, which can be overexpressed to repress ethA. Mutations in inhA or the promoter of inhA can also lead to resistance through changing the binding site or overexpression.[4]

The FDA has placed it in pregnancy category C, because it has caused birth defects in animal studies.[15][16] It is not known whether ethionamide is excreted into breast milk.[8]

Adverse effects

Ethionamide frequently causes gastrointestinal distress with nausea and vomiting which can lead patients to stop taking it.[10] This can sometimes be improved by taking it with food.[8]

Ethionamide can cause hepatocellular toxicity and is contraindicated in patients with severe liver impairment. Patients on ethionamide should have regular monitoring of their liver function tests.[8] Liver toxicity occurs in up to 5% of patients and follows a pattern similar to isoniazid, usually arising in the first 1 to 3 months of therapy, but can occur even after more than 6 months of therapy.[17] The pattern of liver function test derangement is often a rise in the ALT and AST.[17]

Both central neurological side effects such as psychiatric disturbances and encephalopathy, along with peripheral neuropathy have been reported.[8][13] Administering pyridoxine along with ethionamide may reduce these effects and is recommended.[8]

Ethionamide is structurally similar to methimazole, which is used to inhibit thyroid hormone synthesis, and has been linked to hypothyroidism in several TB patients.[18] Periodic monitoring of thyroid function while on ethionamide is recommended.[8]

Interactions

Ethionamide may worsen the adverse effects of other antituberculous drugs being taken at the same time. It boosts levels of isoniazid when taken together and can lead to increased rates of peripheral neuropathy and hepatotoxicity.[8] When taken with cycloserine, seizures have been reported. High rates of hepatotoxicty have been reported when taken with rifampicin.[8] The drug's labeling cautions against excessive alcohol ingestion as it may provoke a psychotic reaction.[15]

Mechanism of action

Ethionamide is a prodrug[19] which is activated by the enzyme ethA, a mono-oxygenase in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and then binds NAD+ to form an adduct which inhibits InhA in the same way as isoniazid. The mechanism of action is thought to be through disruption of mycolic acid.[5][20]

Expression of the ethA gene is controlled by ethR, a transcriptional repressor. It is thought that improving ethA expression will increase the efficacy of ethionamide and prompting interest by drug developers in EthR inhibitors as a co-drug.[4]

Society and culture

- 1314[21]

- 2-ethylisothionicotinamide

- Trecator

- amidazine

- thioamide

It is sold under the brand name Trecator [22] by Wyeth Pharmaceuticals which was purchased by Pfizer in 2009.

References

- Trecator (ethionamide) tablet, film coated (Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Company, a subsidiary of Pfizer Inc.) Archived 2014-03-05 at the Wayback Machine on DailyMed

- "Ethionamide". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- "Standard Chemotherapy". www.hrsa.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-12-15.

- Wolff, Kerstin A.; Nguyen, Liem (2012-09-01). "Strategies for potentiation of ethionamide and folate antagonists against Mycobacterium tuberculosis". Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 10 (9): 971–981. doi:10.1586/eri.12.87. ISSN 1478-7210. PMC 3971469. PMID 23106273.

- "Ethionamide". TB Online. Global Tuberculosis Community Advisory Board. Archived from the original on 2013-09-14. Retrieved 2012-08-18.

- "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- "Ethionamide". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- "Summary of Product Characteristics" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-12-14.

- Auclair, B.; Nix, D. E.; Adam, R. D.; James, G. T.; Peloquin, C. A. (2001). "Pharmacokinetics of Ethionamide Administered under Fasting Conditions or with Orange Juice, Food, or Antacids". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 45 (3): 810–4. doi:10.1128/AAC.45.3.810-814.2001. PMC 90379. PMID 11181366.

- Bennett, John E.; Dolin, Raphael; Blaser, Martin; Mandell, Gerald L (2015). "38 - Antimycobacterial Agents". Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases. ISBN 978-0-323-40161-6. OCLC 889211235.

- Rastogi, Nalin; Labrousse, Valérie; Goh, Khye Seng (1996). "In Vitro Activities of Fourteen Antimicrobial Agents Against Drug Susceptible and Resistant Clinical Isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Comparative Intracellular Activities Against the Virulent H37Rv Strain in Human Macrophages". Current Microbiology. 33 (3): 167–75. doi:10.1007/s002849900095. PMID 8672093.

- "WHO Model Prescribing Information: Drugs Used in Mycobacterial Diseases: Leprosy: Ethionamide and protionamide". apps.who.int. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-12-14.

- Bennett, John E.; Dolin, Raphael; Blaser, Martin; Douglas, R. Gordon (2015). "253 - Mycobacterium avium Complex". Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases. pp. 2832–2843.e3. ISBN 978-0-323-40161-6. OCLC 889211235.

- Belardinelli, Juan M.; Morbidoni, Héctor R. (2013-04-01). "Recycling and refurbishing old antitubercular drugs: the encouraging case of inhibitors of mycolic acid biosynthesis". Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 11 (4): 429–440. doi:10.1586/eri.13.24. ISSN 1478-7210. PMID 23566152.

- "TRECATOR- ethionamide tablet, film coated". Archived from the original on 2016-08-18. Retrieved 2016-12-14.

- "Ethionamide Use During Pregnancy | Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2016-12-21. Retrieved 2016-12-14.

- "Ethionamide". livertox.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-12-24. Retrieved 2016-12-14.

- McDonnell, Marie E.; Braverman, Lewis E.; Bernardo, John (2005). "Hypothyroidism Due to Ethionamide". New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (26): 2757–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM200506303522621. PMID 15987931.

- Vannelli, T. A.; Dykman, A.; Ortiz De Montellano, P. R. (2002). "The Antituberculosis Drug Ethionamide is Activated by a Flavoprotein Monooxygenase". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (15): 12824–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110751200. PMID 11823459.

- Quemard, A; Laneelle, G; Lacave, C (1992). "Mycolic acid synthesis: A target for ethionamide in mycobacteria?". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 36 (6): 1316–21. doi:10.1128/aac.36.6.1316. PMC 190338. PMID 1416831.

- Somner, A.R. (1959). "2-Ethylisothionicotinamide ('1314') in pulmonary tuberculosis: A controlled trial of drug tolerance". Tubercle. 40 (6): 457–461. doi:10.1016/S0041-3879(59)80101-X. PMID 13832783.

- "Trecator and Trecator SC tablet by Wyeth" |"Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-03-14. Retrieved 2014-03-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)