Yaws

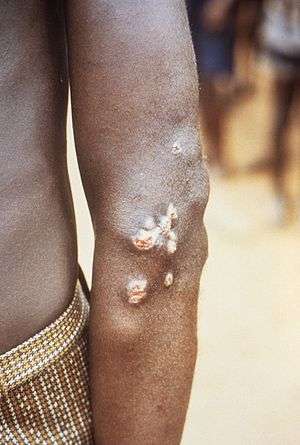

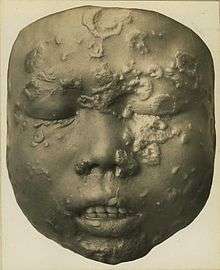

Yaws is a tropical infection of the skin, bones and joints caused by the spirochete bacterium Treponema pallidum pertenue.[3][5] The disease begins with a round, hard swelling of the skin, 2 to 5 centimeters in diameter.[3] The center may break open and form an ulcer.[3] This initial skin lesion typically heals after three to six months.[4] After weeks to years, joints and bones may become painful, fatigue may develop, and new skin lesions may appear.[3] The skin of the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet may become thick and break open.[4] The bones (especially those of the nose) may become misshapen.[4] After five years or more large areas of skin may die, leaving a scar.[3]

| Yaws | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Frambesia tropica, thymosis, polypapilloma tropicum, parangi, bouba, frambösie,[1] pian[2] |

| |

| Nodules on the elbow resulting from a Treponema pallidum pertenue bacterial infection | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Hard swelling of the skin, ulcer, joint and bone pain[3] |

| Causes | Treponema pallidum pertenue spread by direct contact[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, blood antibody tests, polymerase chain reaction[4] |

| Prevention | Mass treatment[4] |

| Medication | Azithromycin, benzathine penicillin[4] |

| Frequency | 46,000-500,000[4][5] |

Yaws is spread by direct contact with the fluid from a lesion of an infected person.[4] The contact is usually of a non-sexual nature.[4] The disease is most common among children, who spread it by playing together.[3] Other related treponemal diseases are bejel (Treponema pallidum endemicum), pinta (Treponema carateum), and syphilis (Treponema pallidum pallidum).[4] Yaws is often diagnosed by the appearance of the lesions.[4] Blood antibody tests may be useful but cannot separate previous from current infections.[4] Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is the most accurate method of diagnosis.[4]

Prevention is, in part, by curing those who have the disease thereby decreasing the risk of transmission.[4] Where the disease is common, treating the entire community is effective.[4] Improving cleanliness and sanitation will also decrease spread.[4] Treatment is typically with antibiotics including: azithromycin by mouth or benzathine penicillin by injection.[4] Without treatment, physical deformities occur in 10% of cases.[4]

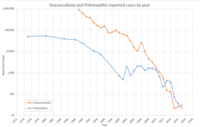

Yaws is common in at least 13 tropical countries as of 2012.[3][4] Almost 85% of infections occurred in three countries—Ghana, Papua New Guinea, and Solomon Islands.[6] The disease only infects humans.[4] Efforts in the 1950s and 1960s by the World Health Organization (WHO) decreased the number of cases by 95%.[4] Since then cases have increased and there are renewed efforts to globally eradicate the disease by 2020.[4] In 1995 the number of people infected was estimated at more than 500,000.[5] In 2016 the number of reported cases was 59,000.[7] Although one of the first descriptions of the disease was made in 1679 by Willem Piso, archaeological evidence suggests that yaws may have been present among human ancestors as far back as 1.6 million years ago.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Within 90 days (but usually less than a month) of infection a painless but distinctive "mother yaw" nodule appears, which enlarges and becomes warty in appearance. Nearby "daughter yaws" may also appear simultaneously.

This primary stage resolves completely within six months. The secondary stage occurs months to years later, with typically widespread skin lesions that vary in appearance, including "crab yaws" on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet with desquamation. These secondary lesions frequently ulcerate and are then highly infectious, but heal after six months or more. About 10% of people then go on to develop tertiary disease within five to ten years (during which further secondary lesions may come and go), with widespread bone, joint and soft tissue destruction, which may include extensive destruction of the bone and cartilage of the nose (Rhinopharyngitis mutilans or "gangosa").

Cause

The disease is transmitted by skin-to-skin contact with an infective lesion, with the bacterium entering through a pre-existing cut, bite or scratch.

T. pallidum pertenue has been identified in non-human primates (baboons, chimpanzees, and gorillas) and studies show that experimental inoculation of human beings with a simian isolate causes yaws-like disease. However, no evidence exists of cross-transmission between human beings and primates, but more research is needed to discount the possibility of a yaws animal reservoir in non-human primates.[3]

Diagnosis

Most often the diagnosis is made clinically. Dark field microscopy of samples taken from early lesions (particularly ulcerative lesions) may show the responsible organism. Blood tests such as VDRL, Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR) and TPHA will also be positive, but there are no current blood tests which distinguish among the four treponematoses.[8]

Prevention

It is currently thought that it may be possible to eradicate yaws although it is not certain that humans are the only reservoir of infection.[9] A single injection of long-acting penicillin or other beta lactam antibiotic cures the disease and is widely available,[10] and the disease is believed to be highly localised.

In April 2012, WHO initiated a new global campaign for the eradication of yaws, which has been on the WHO eradication list since 2011. According to the official roadmap, elimination should be achieved by 2020.[11][12]

Prior to the most recent WHO campaign, India launched its own national yaws elimination campaign which appears to have been successful.[10][13]

Certification for disease-free status requires an absence of the disease for at least five years. In India this happened on 19 September 2011. In 1996 there were 3,571 yaws cases in India; in 1997 after a serious elimination effort began the number of cases fell to 735. By 2003 the number of cases was 46. The last clinical case in India was reported in 2003 and the last latent case in 2006.[14] India is a country where yaws is now considered to have been eliminated.[15]

In March 2013, WHO convened a new meeting of yaws experts in Geneva to further discuss the strategy of the new eradication campaign. The meeting was significant, and representatives of most countries where yaws is endemic attended and described the epidemiological situation at the national level. The disease is currently known to be present in Indonesia and Timor-Leste in South-East Asia; Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu in the Pacific region; and Benin, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana and Togo in Africa. As reported at the meeting, in several such countries, mapping of the disease is still patchy and will need to be completed before any serious eradication effort could be enforced.[16]

Treatment

Treatment is normally by a single intramuscular injection of penicillin, or by a course of penicillin, erythromycin or tetracycline tablets. A single oral dose of azithromycin was shown to be as effective as intramuscular penicillin.[17] Primary and secondary stage lesions may heal completely, but the destructive changes of tertiary yaws are largely irreversible.

Epidemiology

About three quarters of people affected are children under 15 years of age, with the greatest incidence in children 6–10 years old.[18] Therefore, children are the main reservoir of infection. Because T. pallidum pertenue is temperature- and humidity-dependent, yaws is found in humid tropical regions in South America, Africa, Asia and Oceania.

Mass treatment campaigns in the 1950s reduced the worldwide prevalence from 50–150 million to fewer than 2.5 million; however, during the 1970s there were outbreaks in South-East Asia, and there have been continued sporadic cases in South America. It is unclear how many people worldwide are infected at present.[9]

The global prevalence of this disease and the other endemic treponematoses, bejel and pinta, was reduced by the Global Control of Treponematoses (TCP) programme between 1952 and 1964 from about 50 to 150 million cases to about 2.5 million (a 95 percent reduction). Following the cessation of this program yaws surveillance and treatment became a part of primary health systems of the affected countries. However incomplete eradication led to a resurgence of yaws in the 1970s with the largest number of case found in the Western Africa region.[9][19]

Following the development of orally administered azithromycin as a treatment, the WHO has targeted yaws for eradication by 2020.[20]

History

Examination of remains of Homo erectus from Kenya, that are about 1.6 million years old, has revealed signs typical of yaws. The genetic analysis of the yaws' causative bacteria—Treponema pallidum pertenue—has led to the conclusion that yaws is the most ancient of the four known Treponema diseases. All other Treponema pallidum subspecies probably evolved from Treponema pallidum pertenue. Yaws is believed to have originated in tropical areas of Africa, and spread to other tropical areas of the world via immigration and the slave trade. The latter is likely the way it was introduced to Europe from Africa in the 15th century. The first unambiguous description of yaws was made by the Dutch physician Willem Piso. Yaws was clearly described in 1679 among African slaves by Thomas Sydenham in his epistle on venereal diseases, although he thought that it was the same disease as syphilis. The causative agent of yaws was discovered in 1905 by Aldo Castellani in ulcers of patients from Ceylon.[3]

The current name is believed to be of Carib origin, "yaya" meaning sore.[8]

References

- Rapini RP, Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- James WD, Berger TG, et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0. OCLC 62736861.

- Mitjà O; Asiedu K; Mabey D (2013). "Yaws". The Lancet. 381 (9868): 763–73. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62130-8. PMID 23415015.

- "Yaws Fact sheet N°316". World Health Organization. February 2014. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- Mitjà O; Hays R; Rinaldi AC; McDermott R; Bassat Q (2012). "New treatment schemes for yaws: the path toward eradication" (pdf). Clinical Infectious Diseases. 55 (3): 406–412. doi:10.1093/cid/cis444. PMID 22610931. Archived from the original on 2014-05-18.

- Mitjà, O; Marks, M; Konan, DJ; Ayelo, G; Gonzalez-Beiras, C; Boua, B; Houinei, W; Kobara, Y; Tabah, EN; Nsiire, A; Obvala, D; Taleo, F; Djupuri, R; Zaixing, Z; Utzinger, J; Vestergaard, LS; Bassat, Q; Asiedu, K (June 2015). "Global epidemiology of yaws: a systematic review". The Lancet. Global Health. 3 (6): e324–31. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00011-X. PMC 4696519. PMID 26001576.

- "Number of cases of yaws reported". World Health Organization Global Health Observatory. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- Davis CP, Stoppler MC. "Yaws". MedicineNet.com. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- Capuano, C; Ozaki, M (2011). "Yaws in the Western Pacific Region: A Review of the Literature". Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2011: 642832. doi:10.1155/2011/642832. PMC 3253475. PMID 22235208.

- Asiedu K; Amouzou, B; Dhariwal, A; Karam, M; Lobo, D; Patnaik, S; Meheus, A (2008). "Yaws eradication: past efforts and future perspectives". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 86 (7): 499–500. doi:10.2471/BLT.08.055608. PMC 2647478. PMID 18670655. Archived from the original on 2009-04-21. Retrieved 2009-04-02.

- Maurice, J (2012). "WHO plans new yaws eradication campaign". The Lancet. 379 (9824): 1377–78. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60581-9. PMID 22509526. Archived from the original on 2012-04-15.

- Rinaldi A (2012). "Yaws eradication: facing old problems, raising new hopes". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 6 (11): e18372. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001837. PMC 3510082. PMID 23209846.

- WHO South-East Asia report of an intercountry workshop on Yaws eradication, 2006 Archived 2008-11-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Akbar, S (7 August 2011). "Another milestone for India: Yaws eradication". The Asian Age. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- "Yaws Eradication Programme (YEP)". NCDC, Dte. General of Health Services, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Drug and a syphilis test offer hope of yaws eradication, 2013 Archived 2014-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Mitjà, O; Hays, R; Ipai, A; Penias, M; Paru, R; Fagaho, D; de Lazzari, E; Bassat, Q (Jan 28, 2012). "Single-dose azithromycin versus benzathine benzylpenicillin for treatment of yaws in children in Papua New Guinea: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised trial". The Lancet. 379 (9813): 342–47. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61624-3. PMID 22240407.

- "Yaws". WHO Fact sheet. Archived from the original on 2012-11-01. Retrieved 2012-10-16.

- Rinaldi A (2008). "Yaws: a second (and maybe last?) chance for eradication". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2 (8): e275. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000275. PMC 2565700. PMID 18846236.

- "Eradication of yaws – the Morges Strategy" (pdf). Weekly Epidemiological Record. 87 (20). 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-05-08. Retrieved 2014-05-06.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yaws. |

- "Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue". NCBI Taxonomy Browser. 168.