Epigenetics of schizophrenia

The epigenetics of schizophrenia is the study of how the inherited epigenetic changes is regulated and modified by the environment and external factors, and how these changes shape and influence the onset and development of, and vulnerability to, schizophrenia. Epigenetics also studies how these genetic modifications can be passed on to future generations. Schizophrenia is a debilitating and often misunderstood disorder that affects up to 1% of the world's population.[1] While schizophrenia is a well-studied disorder, epigenetics offers a new avenue for research, understanding, and treatment.

Background

History

Historically, schizophrenia has been studied and examined through different paradigms, or schools of thought. In the late 1870s, Emil Kraepelin started the idea of studying it as an illness. Another paradigm, introduced by Zubin and Spring in 1977, was the stress-vulnerability model where the individual has unique characteristics that give him or her strengths or vulnerabilities to deal with stress, a predisposition for schizophrenia. More recently, with the decoding of the human genome, there had been a focus on identifying specific genes to study the disease. However, the genetics paradigm faced problems with inconsistent, inconclusive, and variable results. The most recent school of thought is studying schizophrenia through epigenetics.[2]

The idea of epigenetics has been described as far back as 1942, when Conrad Waddington described it as how the environment regulated genetics. As the field and available technology has progressed, the term has come to also refer to the molecular mechanisms of regulation. The concept that these epigenetic changes can be passed on to future generations has progressively become more accepted.[3]

While epigenetics is a relatively new field of study, specific applications and focus on mental disorders like schizophrenia is an even more recent area of research.

Schizophrenia

Symptoms

The core symptoms of schizophrenia can be classified into three broad categories. These symptoms are often used to build and study animal models of schizophrenia in the field of epigenetics.[1] Positive symptoms are considered limbic system aberrations, while negative and cognitive symptoms are thought of as frontal lobe abnormalities.[4]

Positive Symptoms:

- Hallucination

- Delusions and paranoia

- Thought disorders

Negative Symptoms:

- Apathy

- Poverty of speech

- Flat or blunted emotions

Cognitive Dysfunctions:

- Impaired working memory

- Disorganized thoughts

- Cognitive impairments[1]

Heritability

There is a great deal of evidence to show that schizophrenia is a heritable disease. One key piece of evidence is a twin study that showed that the likelihood of developing the disease is 53% for one member of monozygotic twins (twins with same genetic code), compared to the 15% for dizygotic twins, who don't share the exact DNA.[5] Others question the evidence of heritability due to different definitions of schizophrenia and the similar environment for both twins.[6][7]

The fact that even monozygotic twins don't share a 100% concordance rate suggests environmental factors play a role in the vulnerability and development of the disorder. There are various environmental factors that have been suggested, including the use of marijuana, complications during pregnancy, socioeconomic status and environment, and maternal malnutrition. As the field of epigenetics advances, these and other external risk factors are likely to be considered in epidemiological studies.[1]

Genetics

Several genes have been identified as important in the study of schizophrenia, but there are a few that have special roles when studying the epigenetic modifications of the disease.

- GAD1- GAD1 codes for the protein GAD67, an enzyme that catalyzes the formation of GABA from glutamate. Individuals with schizophrenia have shown a decrease in GAD67 levels and this deficit is thought to lead to working memory problems, among other impairments.[8]

- RELN- RELN codes for reelin, an extracellular protein that is necessary for formation of memories and learning through plasticity. Reelin is thought to regulate nearby glutamate producing neurons.[1]

Both proteins are created by GABAergic neurons. Several studies have demonstrated that levels of both reelin and GAD67 are downregulated in patients with schizophrenia and animal models.

Research methods

Epigenetics can be studied and researched through various methods. One of the most common methods is looking at postmortem brain tissue of patients with schizophrenia and analyzing them for biomarkers. Other common methods include tissue culture studies of neurons, genome-wide analysis of non-brain cells in living patients (see PBMC), and transgenic and schizophrenic animal models.[1]

Other studies that are currently being done or that can be done in the future include longitudinal studies of patients, "at-risk" populations, and monozygotic twins, and studies that examine specific gene-environment interactions and epigenetic effects.[9]

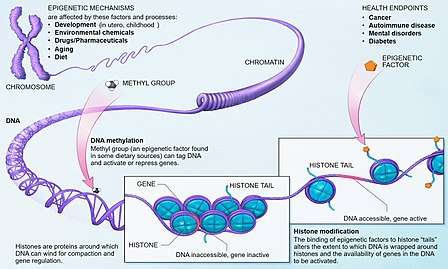

Epigenetic alterations

Epigenetics (translated as "above genetics") is the study of how genes are regulated through reversible and heritable molecular mechanisms. The epigenetic changes modify gene expression through either activation of the gene that codes for a certain protein, or repression of the gene. There are two main categories of modifications: the methylation of DNA and modifications to histones. Research findings have demonstrated that several examples of both of these changes are linked to schizophrenia and its symptoms.[1]

DNA methylation

DNA methylation is the covalent addition of a methyl group to a segment of the DNA code. These -CH3 groups are added to cytosine residues by the DNMT (DNA Methytransferases) enzymes. The binding methyl group to promoter regions interferes with the binding of transcription factors and silences the gene by preventing the transcription of that code.[1] DNA methylation is one of the most well studied epigenetic mechanisms and there have been several findings linking it to schizophrenia.

Methylation of GABAergic genes

It has been consistently shown in various studies that levels of reelin and GAD67 are downregulated in the cortical and hippocampal tissue samples of individuals with schizophrenia. These proteins are used by GABAergic neurons, and abnormalities in their levels could result in some of the symptoms found in individuals with schizophrenia. The genes for these two proteins are found in areas of the genetic code that can be methylated (see CpG island). Recent studies have demonstrated an epigenetic link between the levels of the proteins and schizophrenia. One study found that cortical neurons with lower levels of GAD67 and reelin also showed increased levels of DNMT1, one of the enzymes that adds a methyl group. It has also been shown that a schizophrenic-type state can be induced in mice when they were chronically given l-methionine, a precursor necessary for DNMT activity. These and other findings provide a strong link between epigenetic changes and schizophrenia.[8]

Methylation of BDNF

DNA methylation can also affect expression of BDNF (brain derived neurotrophic factor). The BDNF protein is important for cognition, learning, and even vulnerability to early life trauma. Sun et al. showed that fear condition led to changes in DNA methylation levels in BDNF promoter regions in hippocampal neurons. It was also shown that inhibiting DNMT activity led to change in levels of BDNF in the hippocampus. Methylation of BDNF DNA has also been shown to be affected by post-natal social experiences, stressful environment, and social interaction deprivation. Furthermore, these stimuli have also been linked to increased anxiety, problems with cognition, etc. While a direct link between schizophrenia and BDNF levels hasn't been established, these findings suggest a relation to many problems that are similar to symptoms.[1]

Histone modifications

Histones are proteins that the DNA chromosome are wrapped around. Histones are present as an octamer (set of 8 proteins) and they can be modified through acetylation, methylation, SUMOylation, etc. These changes can either open or close up the chromosome. Thus, depending on which histone is modified and the exact process, histone modifications can either silence or promote gene expression (while DNA methylation almost always silences).

Because the sub-field of histone modifications is relatively new, there aren't many results yet. Some studies have found that patients with schizophrenia have higher levels of methylation at H3 (the 3rd histone in the octamer) in the prefrontal cortex, an area that could be related to the negative symptoms. It has also been shown that histone acetylation and phosphorylation is increased at the promoter for the BDNF protein, which is involved in learning and memory.[1]

More recent studies have found that postmortem brain tissue from patients with schizophrenia had higher levels of HDAC, histone deacetylase, an enzyme that remove acetyl groups from histones. HDAC1 levels are inversely correlated with GAD67 protein expression, which is decreased in patients with schizophrenia.[8]

Heritability

Studies have shown that epigenetic changes can be passed on to future generations through meiosis and mitosis.[10] These findings suggest that environmental factors that the parents face can possibly affect how the child's genetic code is regulated. Research findings have shown this to be true for patients with schizophrenia as well. In rats, the transmission of maternal behavior and even stress responses can be attributed to how certain genes in the hippocampus of the mother are methylated.[1] Another study has shown that the methylation of the BDNF gene, which can be affected by early life stress and abuse, is also transmittable to future generations.[11]

Environmental risks and causes

While there haven't been many studies linking environmental factors to schizophrenia-related epigenetics mechanisms at this point in the field, a few studies have shown interesting results. Advanced paternal age is one of the risk factors for schizophrenia, according to recent research. This is through mutagenesis, which cause further spontaneous changes, or through genomic imprinting. As the parent ages, more and more errors may occur in the epigenetic process.[12] There is also evidence of the association between the inhalation of benzene through the burning of wood and schizophrenic development. This might occur through epigenetic changes.[13] Methamphetamine has also been linked to schizophrenia or similar psychotic symptoms. A recent study found that methamphetamine users had altered DNMT1 levels, similar to how patients with schizophrenia have shown abnormal levels of DNMT1 in GABAergic neurons.[14]

One of the most interesting findings relating an environmental factor with schizophrenic epigenetic mechanisms is exposure to nicotine. It has been widely reported that 80% of patients with schizophrenia use some form of tobacco.[15] Furthermore, smoking appeared to increase cognition in individuals with schizophrenia. However, it was only a recent study Satta et al.that showed that nicotine leads to decreased levels of DNMT1 in GABAergic mouse neurons, a molecule which adds methyl groups to DNA. This led to increased expression of GAD67.[16]

Research limitations

There are several limitations to current research methods and scientific findings. One problem with postmortem studies is that they only demonstrate a single snapshot of a patient with schizophrenia. Thus, it is hard to relate whether biomarker findings are related to the pathology of schizophrenia.

Another limitation is that the most relevant tissue, that of the brain, is impossible to obtain in living, patients with schizophrenia. To work around this, several studies have used more accessible sources, like lymphocytes or germ cell lines, since some studies have shown that epigenetic mutations can be detected in other tissues.

Epigenetic studies of disorders like schizophrenia are also subject to the subjectivity of psychiatric diagnoses and the spectrum-like nature of mental health problems. This problem with classification of mental health problems have led to intermediate phenotypes that might be better fit.[9]

Detection and treatment

The advent of epigenetics as an avenue to pursue schizophrenic research has brought about many possibilities for both early detection, diagnoses, and treatment. While this field is still at an early stage, there have already been promising findings. Some postmortem brain studies looking at the gene expression of histone methylation has shown promising results that might be used for early detection in other patients. However, the bulk of the translational research focus and findings have been on therapeutic interventions.[8]

Therapeutics

Since epigenetic changes are reversible and susceptible pharmacological treatments and drugs, there is a great deal of promise in developing treatments. As many have pointed out, schizophrenia is a lifelong disorder that had widespread effects. Thus, it may not be possible to fully reverse the disease. However, recent findings suggest that it is possible to treat patients with schizophrenia, alleviate symptoms, or improve the efficacy of anti-psychotic medication.[8]

Targeting histones modifications

HDAC (histone deacetylase) inhibitors are one class of drugs that are being investigated. Studies have shown that levels of reelin and GAD67 (which are decreased in schizophrenic animal models) are both upregulated after treatment with HDAC inhibitors. Furthermore, there is the added benefit of selectivity, as HDAC inhibitors can be specific to cell type, tissue type, and even regions of the brain.[8]

HMT (histone demethylase) inhibitors also act on histones. They prevent the demethylation of the H3K4 histone protein and open up that part of the chromatin. Tranylcypromine, an antidepressant, has been shown to have HMT inhibitory properties, and in a study, treatment of patients with schizophrenia with tranylcypromine showed improvements regarding negative symptoms.[8]

Targeting DNA methylation

DNMT inhibitors have also been shown to increase levels of the reeling protein and GAD67 in cell cultures. Some of the current DNMT inhibitors, however, like zebularine and procainamide, do not cross the blood brain barrier and would not prove as effective a treatment. While DNMT inhibitors would prevent the addition of a methyl group, there is also research done on DNA demethylate inducers, which would pharmacologically induce the removal of methyl groups. Current antipsychotic drugs, like clozapine and sulpiride, have been shown to also induce demethylation.[8]

See also

References

- Roth TL, Lubin FD, Sodhi M, Kleinman JE (September 2009). "Epigenetic mechanisms in schizophrenia". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1790 (9): 869–77. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.06.009. PMC 2779706. PMID 19559755.

- Kaplan RM (October 2008). "Being Bleuler: the second century of schizophrenia". Australas Psychiatry. 16 (5): 305–11. doi:10.1080/10398560802302176. PMID 18781458.

- Pidsley R, Mill J (January 2011). "Epigenetic studies of psychosis: current findings, methodological approaches, and implications for postmortem research". Biol. Psychiatry. 69 (2): 146–56. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.029. PMID 20510393.

- Hooley JM, Butcher JN, Mineka S (2009). Abnormal Psychology (14th Edition) (MyPsychLab Series). Boston, Mass: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 978-0-205-59495-5.

- Sham P (July 1996). "Genetic epidemiology". Br. Med. Bull. 52 (3): 408–33. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011557. PMID 8949247.

- Fosse R, Joseph J, Richardson K (2015). "A critical assessment of the equal-environment assumption of the twin method for schizophrenia". Front Psychiatry. 6: 62. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00062. PMC 4411885. PMID 25972816.

- "The Missing Gene: Psychiatry, Heredity, and the Fruitless Search for Genes" Author Jay Joseph

- Gavin DP, Sharma RP (May 2010). "Histone modifications, DNA methylation, and schizophrenia". Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 34 (6): 882–8. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.010. PMC 2848916. PMID 19879893.

- Rutten BP, Mill J (November 2009). "Epigenetic mediation of environmental influences in major psychotic disorders". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 35 (6): 1045–56. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp104. PMC 2762629. PMID 19783603.

- Goto T, Monk M (June 1998). "Regulation of X-chromosome inactivation in development in mice and humans". Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62 (2): 362–78. PMC 98919. PMID 9618446.

- Roth TL, Lubin FD, Funk AJ, Sweatt JD (May 2009). "Lasting epigenetic influence of early-life adversity on the BDNF gene". Biol. Psychiatry. 65 (9): 760–9. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.028. PMC 3056389. PMID 19150054.

- van Os J, Rutten BP, Poulton R (November 2008). "Gene-environment interactions in schizophrenia: review of epidemiological findings and future directions". Schizophr Bull. 34 (6): 1066–82. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn117. PMC 2632485. PMID 18791076.

- Ross CM (April 2009). "Epigenetics, traffic and firewood". Schizophr. Res. 109 (1–3): 193. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.007. PMID 19217264.

- Oh G, Petronis A (November 2008). "Environmental studies of schizophrenia through the prism of epigenetics". Schizophr Bull. 34 (6): 1122–9. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn105. PMC 2632494. PMID 18703665.

- Kelly C (2000). "Cigarette smoking and schizophrenia". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 6 (5): 327–331. doi:10.1192/apt.6.5.327.

- Satta R, Maloku E, Zhubi A, Pibiri F, Hajos M, Costa E, Guidotti A (October 2008). "Nicotine decreases DNA methyltransferase 1 expression and glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 promoter methylation in GABAergic interneurons". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (42): 16356–61. doi:10.1073/pnas.0808699105. PMC 2570996. PMID 18852456.

Further reading

- "Epigenetics". Science Online Special Collection. AAAS. October 2010.

- Akbarian S (2010). "Epigenetics of schizophrenia". Curr Top Behav Neurosci. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. 4: 611–28. doi:10.1007/7854_2010_38. ISBN 978-3-642-13716-7. PMID 21312415.

- Gavin DP, Sharma RP (May 2010). "Histone modifications, DNA methylation, and schizophrenia". Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 34 (6): 882–8. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.010. PMC 2848916. PMID 19879893.

- Mill J, Petronis A (2011). Brain, Behavior and Epigenetics (Epigenetics and Human Health). Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-17425-4.

- Oh G, Petronis A (November 2008). "Environmental studies of schizophrenia through the prism of epigenetics". Schizophr Bull. 34 (6): 1122–9. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn105. PMC 2632494. PMID 18703665.

- Roth TL, Lubin FD, Sodhi M, Kleinman JE (September 2009). "Epigenetic mechanisms in schizophrenia". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1790 (9): 869–77. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.06.009. PMC 2779706. PMID 19559755.

External links