Endoscopic endonasal surgery

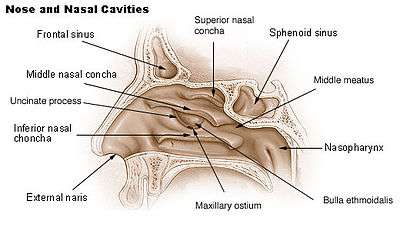

Endoscopic endonasal surgery is a minimally invasive technique used mainly in neurosurgery and otolaryngology. A neurosurgeon or an otolaryngologist, using an endoscope that is entered through the nose, fixes or removes brain defects or tumors in the anterior skull base. Normally an otolaryngologist performs the initial stage of surgery through the nasal cavity and sphenoid bone; a neurosurgeon performs the rest of the surgery involving drilling into any cavities containing a neural organ such as the pituitary gland.

| Endoscopic endonasal surgery | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | otolaryngology |

Introduction

History of endoscopic endonasal surgery

Antonin Jean Desomeaux, a urologist from Paris, was the first person to use the term, endoscope.[1] However, the precursor to the modern endoscope was invented in the 1800s when a physician in Frankfurt, Germany by the name of Philipp Bozzini, developed a tool to see the inner workings of the body.[2] Bozzini called his invention a Light Conductor, or Lichtleiter in German, and later wrote about his experiments on live patients with this device that consisted of an eyepiece and a container for a candle.[1] Following Bozzini's success, The University of Vienna starting using the device to test its practicality in other forms of medicine. After Bozzini's device received negative results from live human trials, it had to be discontinued. However, Maximilian Nitze and Joseph Leiter used the invention of the light bulb by Thomas Edison to make a more refined device similar to modern day endoscopes. This iteration was used for urological procedures, and eventually otolaryngologists began to use Nitze and Leiter's device for eustachian tube manipulation and removal of foreign bodies.[2] The endoscope made its way to the US when Walter Messerklinger began teaching David Kennedy at Johns Hopkins Hospital.

The transsphenoidal and intracranial approaches to pituitary tumors began in the 1800s but with little success. Gerard Guiot popularized the transphenoidal approach which later became part of the neurosurgical curriculum, however he himself discontinued the use of this technique because of inadequate sight.[1] In the late 1970s, the endoscopic endonasal approach was used by neurosurgeons to augment microsurgery which allowed them to view objects out of their line of sight. Another surgeon, Axel Perneczky, is considered to be a pioneer of the use of an endoscope in neurosurgery. Perneczky said that endoscopy, "improved appreciation of micro-anatomy not apparent with the microscope."[1]

Endoscopic instrumentation

The endoscope consists of a glass fiber bundle for cold light illumination, a mechanical housing, and an optics component with four different views: 0 degree for straight forward, 30 degrees for forward plane, 90 degrees for lateral view, and 120 degrees for retrospective view.[3] For endoscopic endonasal surgery, rigid rod-lens endoscopes are used for better quality of vision, since these endoscopes are smaller than the normal endoscope used colonoscopies.[2] The endoscope has an eyepiece for the surgeon, but it is rarely used because it requires the surgeon to be in a fixed position. Instead, a video camera broadcasts the image to a monitor that shows the surgical field.

Areas of interest for surgical planning

Several specialties need to be involved to determine the complete surgical plan. These include: an Endocrinologist, a Neuroradiologist, an Ophthalmologist, a Neurosurgeon, and an Otolaryngologist.

Endocrinology

An endocrinologist is only involved in preparation for an endoscopic endonasal surgery, if the tumor is located on the pituitary gland. The tumor is first treated pharmacologically in two ways: controlling the levels of hormones that the pituitary gland secretes and reducing the size of the tumor. If this approach does not work, the patient is referred to surgery. The main types of pituitary adenomas are:

- PRL-secreting or prolactinomas: These are the most common pituitary tumors. They are associated with infertility, gonad, and sexual dysfunction because they increase the secretion of prolactin or PRL. One drug that endocrinologist use is bromocriptine (BRC), which normalizes PRL levels and has been shown to lead to tumor shrinkage. Other drugs to treat prolactinomas include quinagolide (CV) or cabergoline (CAB) acting as dopamine (D2) antagonists. Endoscopic endonasal surgery is normally performed as a last resort when the tumor is resistant to the drugs, shows no tumor shrinkage, or the PRL levels cannot be normalized.[3]

- GH-secreting: A very rare condition that is a result of the increase in the secretion of growth hormone. There are currently less than 400,000 cases worldwide and approximately 30,000 new cases every year. Despite the rarity of this condition, these tumors constitute 16% of the pituitary tumors that are removed. The tumor normally results in acral enlargement, arthropathy, hyperhidrosis, changes in facial features, soft tissue swelling, headaches, visual changes, or hypopituitarism. Since pharmacological therapy has had little effect on these tumors, a trans-sphenoidal surgery to remove part of the pituitary gland is the first treatment option.[3]

- TSH-secreting: Another rare condition only resulting in 1% of pituitary surgeries is a result of the increase in the secretion of the thyroid-stimulating hormone. This tumor leads to hyperthyroidism, resulting in headaches and visual disturbances. Although surgery is the first step of treatment, it does not usually cure the patient. After surgery, patients are treated by somatostatin analogues, a type of hormone replacement therapy, because TSH related tumors increase the expression of somatostatin receptors.[3]

- ACTH-secreting: This tumor is a result of the increase in the secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and leads to Cushing's syndrome. Pharmacology has little effect and therefore surgery is the best option. Removal of the tumor results in an 80%-90% cure rate.[3]

Neuroradiology

A neuroradiologist takes images of the defect so that the surgeon is prepared on what to expect before surgery. This includes identifying the lesion or tumor, controlling the effects of the medical therapy, defining the spatial situation of the lesions, and verifying the removal of the lesions.[3] The lesions associated with endoscopic endonasal surgery include:

- Pituitary microadenomas

- Pituitary macroadenomas

- Rathke's cleft cysts

- Pituitary inflammatory disease

- Pituitary metastasis

- Empty Sella

- Craniopharyngiomas

- Meningiomas

- Chiasmatic and Hypothalamic gliomas

- Germinomas

- Tuber Cinereum Hamartomas

- Arachnoid cysts

- Neurinomas of the trigeminal nerve

Ophthalmology

Some suprasellar tumors invade the chiasmatic cistern, causing impaired vision. In these cases, an ophthalmologist maintains optic health by administering pre-surgical treatment, advising proper surgical techniques so that the optic nerve is not in danger, and managing post-surgery eye care. Common problems include:

- Visual field defects

- Reduced visual activity

- Visually evoked potential (VEP) abnormalities

- Color blindness

- Eye motility impairment

Surgical approaches to the anterior skull base

Transnasal Approach

The transnasal approach is used when the surgeon needs to access the roof of the nasal cavity, the clivus, or the odontoid. This approach is used to remove chordomas, chondrosarcoma, inflammatory lesions of the clivus, or metastasis in the cervical spine region. The anterior septum or posterior septum is removed so that the surgeon can use both sides of the nose. One side can be used for a microscope and the other side for a surgical instrument, or both sides can be used for surgical instruments.[2]

Transsphenoidal approach

This approach is the most common and useful technique of endoscopic endonasal surgery and was first described in 1910 concurrently by Harvey Cushing and Oskar Hirsch.[4][5] This procedure allows the surgeon to access the sellar space, or sella turcica. The sella is a cradle where the pituitary gland sits. Under normal circumstances, a surgeon would use this approach on a patient with a pituitary adenoma. The surgeon starts with the transnasal approach prior to using the transsphenoidal approach. This allows access to the sphenoid ostium and sphenoid sinus. The sphenoid ostium is located on the anterosuperior surface of the sphenoid sinus. The anterior wall of the sphenoid sinus and the sphenoid rostrum is then removed to allow the surgeon a panoramic view of the surgical area.[2] This procedure also requires the removal of the posterior septum to allow the use of both nostrils for tools during surgery. There are several triangles of blood vessels traversing this region, which are just very delicate areas of blood vessels that can be deadly if injured.[2][6] A surgeon uses stereotactic imaging and a micro Doppler to visualize the surgical field.

The invention of the angled endoscope is used to go beyond the sella to the suprasellar (above the sellar) region. This is done with the addition of four approaches. First the transtuberculum and transplanum approaches are used to reach the suprasellar cistern. The lateral approach is then used to reach the medial cavernous sinus and petrous apex. Lastly, the inferior approach is used to reach the superior clivus. It is important that the Perneczky triangle is treated carefully. This triangle has optic nerves, cerebral arteries, the third cranial nerve, and the pituitary stalk. Damage to any of these could provide a devastating post-surgical outcome.[2][7]

Transpterygoidal approach

The transpterygoidal approach enters through the posterior edge of the maxillary sinus ostium and posterior wall of the maxillary sinus. This involves penetrating three separate sinus cavities: the ethmoid sinus, the sphenoidal sinus, and the maxillary sinus. Surgeons use this method to reach the cavernous sinus, lateral sphenoid sinus, infra temporal fossa, pterygoid fossa, and the petrous apex. Surgery includes a uninectomy (removal of the osteomeatal complex), a medial maxillectomy (removal of maxilla), an ethmoidectomy (removal of ethmoid cells and/or ethmoid bone), a sphenoidectomy (removal of part of sphenoid), and removal of the maxillary sinus and the palatine bone. The posterior septum is also removed at the beginning to allow use of both nostrils.[2]

Transethmoidal approach

This approach makes a surgical corridor from the frontal sinus to the sphenoid sinus. This is done by the complete removal of the ethmoid bone, which allows a surgeon to expose the roof of the ethmoid, and the medial orbital wall. This procedure is often successful in the removal of small encephaloceles of the ethmoid osteomas of the ethmoid sinus wall or small olfactory groove meningiomas. However, with larger tumors or lesions, one of the other approaches listed above is required.[2]

Different approaches to specific regions

Approach to sellar region

For removal of a small tumor, it is accessed through one nostril. However, for larger tumors, access through both nostrils is required and the posterior nasal septum must be removed. Then the surgeon slides the endoscope into the nasal choana until the sphenoid ostium is found. Then the mucosa around the ostium is cauterized for microadenomas and removed completely for macroadenomas. Then the endoscope enters the ostium and meets the sphenoid rostrum where the mucosa is retracted from this structure and is removed from the sphenoid sinus to open the surgical pathway. At this point, imaging and Doppler devices are used to define the important structures. Then the floor of the sella turcica is opened with a high speed drill being careful to not pierce the dura mater. Once the dura is visible, it is cut with microscissors for precision. If the tumor is small, the tumor can be removed by an en bloc procedure, which consists of cutting the tumor into many sections for removal. If the tumor is larger, the center of the tumor is removed first, then the back, then the sides, then top of the tumor to make sure that the arachnoid membrane does not expand into the surgical view. This will happen if the top part of the tumor is taken out too early. After tumor removal, CSF leaks are tested for with fluorescent dye, and if there are no leaks, the patient is closed.[2]

Approach to suprasellar region

This technique is the same as to the sellar region. However the tuberculum sellae is drilled into instead of the sella. Then an opening is made that extends halfway down the sella to expose the dura, and the intercavernous sinuses is exposed. When the optic chiasm, optic nerve, and pituitary gland are visible, the pituitary gland and optic chasm are pushed apart to see the pituitary stalk. An ethmoidectomy is performed,[2] the dura is then cut, and the tumor is removed. These types of tumors are separated into two types:

- Prechiasmal Lesions: This tumor is closest to the dura. The tumor is decompressed by the surgeon. After decompression, the tumor is removed taking care to not disrupt any optic nerve or major arteries.[2]

- Postchiasmal Lesions: This time the pituitary stalk is in the front because the tumor is pushing it towards the area the dura was opened. Removal then starts on both sides of the stalk to preserve the connection between the pituitary and the hypothalamus and above pituitary gland to protect the stalk. The tumor is carefully removed and the patient is closed up.[2]

Skull base reconstruction

When there is a tumor, injury, or some type of defect at the skull base whether the surgeon used an endoscopic or open surgical method, the problem still arises of providing separation of the cranial cavity and cavity between the sinuses and nose to prevent cerebrospinal fluid leakage through the opening referred to as a defect.[8]

For this procedure, there are two ways to start: with a free graft repair or with a vascularized flap repair. The free grafts use secondary material like cadaver flaps or titanium mesh to repair the skull base defects, which is very successful (95% without CSF leaks) with small CSF fistulas or small defects.[9] The local or regional vascularized flaps are pieces of tissue relatively close to the surgery site that have been mostly freed up but are still attached to the original tissue. These flaps are then stretched or maneuvered onto the desired location. When technology advanced and larger defects could be fixed endoscopically, more and more failures and leaks started to occur with the free graft technique. The larger defects are associated with a wider dural removal and an exposure to high flow CSF, which could be the reason for failure among the free graft.[9]

Pituitary gland surgery

This surgery is turned from a very serious surgery into a minimally invasive one through the nose with the use of the endoscope. For instance craniopharyngiomas (CRAs) are starting to be removed via this method. Dr. Paolo Cappabianca described the perfect CRA for this surgery to be a median lesion with a solid parasellar component (beside the sellar) or encasement of the main neuromuscular structures that are localized in the subchiasmatic (below the optic chiasm) and retrochiasmatic (behind the optic chiasm) regions. He also says that when these conditions are met, endoscopic endonasal surgery is a valid surgical option.[10] For a case study on large adenomas, the doctors showed that out of 50 patients, 19 had complete tumor removal, 9 had near complete removal, and 22 had partial removal. The partial removal came from the tumors extending into more dangerous areas. They concluded that endoscopic endonasal surgery was a valid option for surgery if the patients used pharmacological therapy after surgery.[11] Another study showed that with endoscopic endonasal surgery 90% of microadenomas could be removed, and that 2/3 of normal macroadenomas could be removed if they did not go into the cavernous sinus, which means fragile blood vessel triangles would have to be dealt with so only 1/3 of those patients recovered.[12]

3-D approach vs 2-D approach

The newer 3-D technique is gaining ground as the ideal way to do surgery because it gives the surgeon a better understanding of the spatial configuration of what they are seeing on a computer screen. Dr. Nelson Oyesiku at Emory University helped develop the 3-D technique. In an article he helped write, he and the other authors compared the effects of the 2-D technique vs the 3-D technique on patient outcome. It showed that the 3-D endoscopy gave the surgeon more depth of field and stereoscopic vision and that the new technique did not show any significant changes in patient outcomes during or after surgery.[13]

Endoscopic techniques vs open techniques

In a case study from 2013, they compared the open vs endoscopic techniques for 162 other studies that contained 5,701 patients.[14] They only looked at four tumor types: the olfactory groove meningiomas (OGM), tuberculum sellae meningiomas(TSM), craniopharyngiomas (CRA), and clival chordomas (CHO). They looked at gross total resection and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks, neurological death, post-operative visual function, post operative diabetes insipidus, and post-operative obesity. The study showed that there was a greater chance of CSF leaks with endoscopic endonasal surgery. The visual function improved more with endoscopic surgery for TSM, CRA, and CHO patients. Diabetes insipidus occurred more in open procedure patients. The endoscopic patients showed a higher recurrence rate. In another case study on CRAs,[15] they showed similar results with the CSF leaks being more of a problem in endoscopic patients. Open procedure patients showed a higher rate of post operative seizures as well. Both of these studies still suggest that despite the CSF leaks, that the endoscopic technique is still an appropriate and suitable surgical option. Otologic surgery, which is traditionally performed via an open approach using a microscope, may also be performed endoscopically, and is called Endoscopic Ear Surgery or EES.

References

- Doglietto F, Prevedello DM, Jane JA, Han J, Laws ER (2005). "Brief history of endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery--from Philipp Bozzini to the First World Congress of Endoscopic Skull Base Surgery". Neurosurg Focus. 19 (6): E3. doi:10.3171/foc.2005.19.6.4. PMID 16398480.

- Anand, Vijay K. (2007). Practical Endoscopic Skull Base Surgery. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing. ISBN 978-159756060-3.

- de Divitiis, Enrico (2003). Endoscopic Endonasal Transsphenoidal Surgery. Austria: Springer-Verlag/Wien. ISBN 978-3211009727.

- Liu, JK.; Cohen-Gadol, AA.; Laws, ER.; Cole, CD.; Kan, P.; Couldwell, WT.; Cushing, H.; Hirsch, O. (Dec 2005). "Harvey Cushing and Oskar Hirsch: early forefathers of modern transsphenoidal surgery". J Neurosurg. 103 (6): 1096–104. doi:10.3171/jns.2005.103.6.1096. PMID 16381201.

- Lanzino, Giuseppe; Laws, Edward R., Jr.; Feiz-Erfan, Iman; White, William L. (2002). "Transsphenoidal Approach to Lesions of the Sella Turcica: Historical Overview". Barrow Quarterly (18 ed.) (3). Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- Cavallo LM, Cappabianca P, Galzio R, Iaconetta G, de Divitiis E, Tschabitscher M (2005). "Endoscopic transnasal approach to the cavernous sinus versus transcranial route: anatomic study". Neurosurgery. 56 (2 Suppl): 379–89, discussion 379–89. doi:10.1227/01.neu.0000156548.30011.d4. PMID 15794834.

- Perneczky, A.; E. Knosp; Ch. Matula (1988). "Cavernous Sinus Surgery Approach Through the Lateral Wall". Acta Neurochirurgica. 92 (1–4): 76–82. doi:10.1007/BF01401976. PMID 3407478.

- Snyderman, Carl H.; Kassam, Amin B.; Carrau, Ricardo; Mintz, Arlan (January 2007). "Endoscopic Reconstruction of Cranial Base Defects following Endonasal Skull Base Surgery". Skull Base. 17 (1): 73–78. doi:10.1055/s-2006-959337. PMC 1852577. PMID 17603646.

- Harvey, R.J.; Parmar, P.; Sacks, R.; Zanation, A. M. (2012). "Endoscopic skull base reconstruction of large dural defects: a systematic review of published evidence". Laryngoscope. 122 (2): 452–459. doi:10.1002/lary.22475. PMID 22253060.

- Cappabianca, Paolo; Cavallo L (February 2012). "The Evolving Role of Transsphenoidal Route in the Management of Craniopharyngiomas". World Neurosurgery. 2. 77 (2): 273–274. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2011.08.040. PMID 22120287.

- Gondim, Jackson; Almerida JP; Albuquerque LAF; Gomes EF; Schops M (August 2013). "Giant Pituitary Adenomeas: Surgical outcomes of 50 cases operated by the endonasal endoscopic approach". World Neurosurgery. 82 (1–2): e281–e290. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2013.08.028. PMID 23994073.

- Hofstetter, Cristoph; Anand VK; Schwartz TH (2011). "Endoscopic transsphenoidal pituitary surgery". Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 22 (3): 206–214. doi:10.1016/j.otot.2011.09.002.

- Kari, Elina; Oyesiku NM; Dadashev V; Wise SK (February 2012). "Comparison of traditional 2-dimensional endoscopic pituitary surgery with new 3-dimensional endoscopic technology: intraoperative and early postoperative factors". Allergy and Rhinology. 2 (1): 2–8. doi:10.1002/alr.20036. PMID 22311834.

- Graffeo, Christopher; Dietrich AR; Grobelny B; Zhang M; Goldberg JD; Golfinos JG; Lebowitz T; Kleinberg D; Placantonakis DG (September 2013). "A panoramic view of the skull base: systematic review of open and endoscopic endonasal approaches to four tumors". Pituitary. 17 (4): 349–356. doi:10.1007/s11102-013-0508-y. PMC 4214071. PMID 24014055.

- Komotar, Ricardo; Starke RM; Raper DMS; Anand VK; Schwartz TH (February 2012). "Endoscopic Endonasal Compared with Microscopic Transsphenoidal and Open Transcranial Resection of Craniopharyngiomas". World Neurosurgery. 77 (2): 329–341. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2011.07.011. PMID 22501020.