Empty sella syndrome

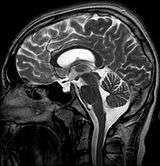

Empty sella syndrome (ESS) is the condition when the pituitary gland shrinks or becomes flattened, filling the sella turcica with cerebrospinal fluid instead of the normal pituitary.[2] ESS can be found in the diagnostic workup of pituitary disorders, or as an incidental finding when imaging the brain.[1]

| Empty sella syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Pituitary - empty sella syndrome[1] |

| |

| MRI of Empty Sella | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Causes | Arachnoid presses down on gland (another possibility is a Tumor, Radiation therapy)[1] |

| Diagnostic method | MRI, CT scan[1] |

| Medication | Manage abnormal hormone levels[1] |

Signs/symptoms

If there are symptoms, people with empty sella syndrome can have headaches and vision loss. Additional symptoms would be associated with Hypopituitarism.[3][4] Additional symptoms are as follows:

- Abnormality (middle ear ossicles)

- Cryptorchidism

- Dolichocephaly

- Arnold-Chiari type I malformation

- Meningocele

- Patent ductus arteriosus

- Muscular hypotonia

- Platybasia

Cause

The cause of this condition is divided into primary and secondary, as follows:

- The cause of this condition in terms of secondary empty sella syndrome happens when a tumor or surgery damages the gland, this is an acquired manner of the condition.[1]

- ~70% of patients with Idiopathic intracranial hypertension will have empty sella on MRI

- The cause of primary empty sella syndrome is a congenital defect (diaphragma sellae)[5]

Mechanism

The normal mechanism of the pituitary gland sees that it controls the hormonal system, which therefore have an effect on growth, sexual development and adrenocortical function. The gland is divided into anterior and posterior.[6][7]

Its pathophysiology is such that individuals affected with the condition can have cerebrospinal fluid build-up, which in turn causes intracranial pressure leading to headaches for the individual.[8]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of ESS, done via examination (and test), may be linked to early onset of puberty, growth hormone deficiency or pituitary gland dysfunction(at an early age).[2] Additionally there is:

Classification

There are two types of ESS: primary and secondary.

- Primary ESS happens when a small anatomical defect above the pituitary gland increases pressure in the sella turcica and causes the gland to flatten out along the interior walls of the sella turcica cavity.[3] Primary ESS is associated with obesity and increase in intracranial pressure in women.[9]In most cases, especially in people with primary ESS, there are no symptoms and it does not affect life expectancy. Some researchers have estimated that less than 1% of affected people ever develop symptoms of the condition.[10]

- Secondary ESS is the result of the pituitary gland regressing within the cavity after an injury, surgery, or radiation therapy.[3] Individuals with secondary ESS due to destruction of the pituitary gland have symptoms that reflect the loss of pituitary functions, such as intolerance to stress and infection.

Differential diagnosis

The major differential to consider in empty sella syndrome is intracranial hypertension, of both unknown and secondary causes, and an epidermoid cyst, which can mimic cerebrospinal fluid due to its low density on CT scans, although MRI can usually distinguish the latter diagnosis.[11]

Treatment

In terms of management, unless the syndrome results in other medical problems, treatment for endocrine dysfunction associated with pituitary malfunction is symptomatic and thus supportive;however, in some cases, surgery may be needed.[2]

References

- "Empty sella syndrome: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- "Empty Sella Syndrome Information Page | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". www.ninds.nih.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-05.

- "Empty sella syndrome | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-05.

- Cecil, Russell La Fayette; Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. (2012). Goldman's Cecil Medicine, Expert Consult Premium Edition -- Enhanced Online Features and Print, Single Volume,24: Goldman's Cecil Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1256. ISBN 978-1437716047. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- Disorders, National Organization for Rare (2003). NORD Guide to Rare Disorders. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 530. ISBN 9780781730631. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- pmhdev (2015-01-07). "How does the pituitary gland work?". PubMed Health.

- Nussey, Stephen; Whitehead, Saffron (2001-01-01). The pituitary gland. BIOS Scientific Publishers.

- Horton, Arthur MacNeill (2012-01-01). The Encyclopedia of Neuropsychological Disorders. Springer Publishing Company. p. 282. ISBN 9780826198549.

- Fouad, Wael (2011-06-01). "Review of empty sella syndrome and its surgical management". Alexandria Journal of Medicine. 47 (2): 139–147. doi:10.1016/j.ajme.2011.06.005.

- "Empty sella syndrome: Prognosis". rarediseases. Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- González-Tortosa, J (2009). "Primary empty sella: Symptoms, physiopathology, diagnosis and treatment" (PDF). Neurocirugia (Asturias, Spain). 20 (2): 132–51. doi:10.1016/s1130-1473(09)70180-0. PMID 19448958.

Further reading

- Disorders, National Organization for Rare (2003). NORD Guide to Rare Disorders. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781730631. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- Becker, Kenneth L. (2001-01-01). Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781717502.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|